Forget Iced Coffee – Mexican Chocolate Frío Is The Pick-Me-Up You Need

Chocolate frio may seem like a Spanglish phrase, but nope, it seems that the Spanish word for "chocolate" is also "chocolate." "Frio," for those of you who took French or Mandarin in high school, means "cold," so the drink is essentially the opposite of hot chocolate: cold chocolate.

So how is chocolate frio not just chocolate milk? Well, in a manner of speaking, it is, although it's quite a bit different from the simple concoction made from Hershey's syrup or Nestle Quik. While recipes vary quite a bit from cook to cook –- or website to website, to give you a more accurate picture of our methodology — most of them do seem to involve more than just milk and chocolate flavoring. Chocolate milk, too, doesn't seem to have much of a backstory, at least not one that we've been unable to unearth, although we did dig up the fun fact that Nestlé Quik was introduced in 1948. Chocolate frio, however, has quite a long and interesting pedigree, one that may date back as long as chocolate itself.

History of chocolate frio

The first people to have enjoyed a chocolaty beverage seem to have been the Maya, who lived in a climate conducive to cultivating cacao trees. Some 3.500 years ago they began mixing crushed cacao beans with chiles and cornmeal to make a drink that today some hipster cafe would probably saddle with the cutesly moniker of Triple-C. As the Mayan language didn't work that way, they instead called the drink xocolatl, which meant "bitter water" — sounds like that drink could have used a little sugar. While xocolatl may have been the precursor to chocolate frio, it differed in one significant way: The Mayans apparently preferred to drink it hot.

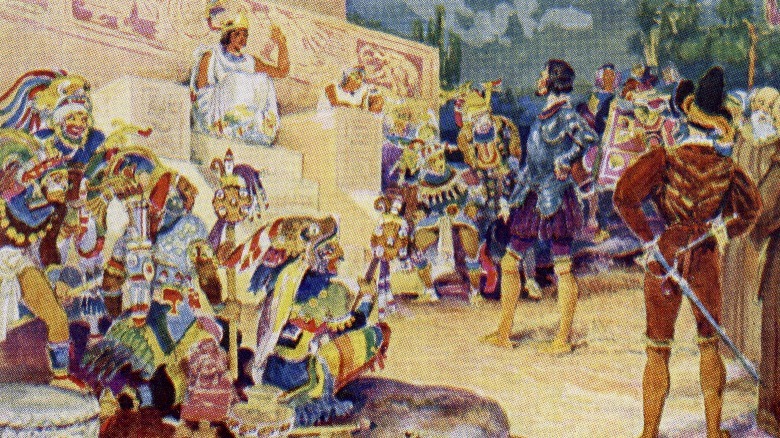

The Aztecs were huge fans of the cacao tree, with their Emperor Montezuma being perhaps the original chocoholic. As they lived in an area where none of these trees grew, though, they had to get their bean fix either from trade or conquest. Once cacao was acquired, the precious pods were ground into powder and mixed with water, with the elite often flavoring the drink with seasonings such as vanilla. The super-elite might even drink it from golden goblets — Montezuma is said to have downed 50 cups per day from such a vessel.

While the Aztecs preferred their chocolate cold, the Spaniards did not agree. They, like the Mayans, preferred hotter brew and even named the beverage chocolatl, a multicultural mashup that combined the Mayan word for hot (chocol) with the Aztec one for water (atl).

How chocolate frio is made

Many recipes for chocolate frio start out with solid discs of Mexican chocolate, but others may include either cocoa or cacao powder instead. As tastes have changed since Montezuma's time, typically a sweetener of some sort is used as well, such as sugar, honey, agave, or even maple syrup although this last-named lends it a pan-North American air by incorporating a little taste of Canada. Chocolate frio very often includes flavorings such as cinnamon, pepper, salt, and vanilla, as well.

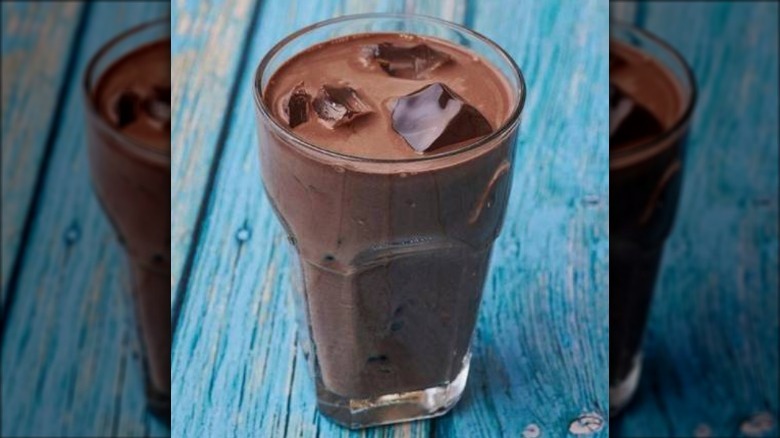

Whichever type of chocolate is used, this cold chocolate drink may well start off with some heat as the chocolate and seasonings are often simmered in milk (either dairy or plant, as preferred). The drink is then rendered "frio" with the addition of some cold milk and/or ice cubes. It's also possible to make a slushie version by blending the chocolate frio with ice cubes. This turns it into a Mexican-style version of the drink oxymoronically known as frozen hot chocolate.

Some like it foamy

Yet another variant of chocolate frio involves taking the basic drink and making it foamy, which is actually in line with how the ancient Maya drank their hot chocolate. Their low-tech frothing method involved pouring it from a vessel held high to another one down low, although today we have access to more complex, but less messy, equipment such as blenders and handheld or automatic milk frothers. Some, however, like to do things old school by using a tool called a molinillo.

Molinillo is a Spanish-ized version of the Nahuatl word moliniani, Nahuatl being the language that the Aztecs spoke, and Montezuma's personal chocolatier (surely he must have had one on staff) may have used such a tool to foam up his proto-chocolate frio. The meaning of the word is something like "wiggle," and the molinillo is basically a kind of stick that is used not to stir, but to twist or spin. This is facilitated by the carved handle of the tool which can be grasped between the palms and spun to create a vortex. The resulting froth is light and airy and, as opposed to a cappuccino, where the frothed milk sits atop the espresso, the molinillo froth is dispersed throughout the chocolate frio.

Chocolate frio is not just from Mexico

Chocolate frio may have originated with the Aztecs, who, along with the Maya, pioneered chocolate consumption in general. Still, as with most good things, it spread by word of mouth. the word in question probably being Nahuatl for "yummy." Eventually, the word, and the dish itself, was translated into Spanish and the deliciosa bebida known as chocolate frio spread throughout Latin America.

Today, this drink is known and loved throughout the Spanish-speaking world, including in Spain itself despite the fact that the conquistadores preferred a warmer Mayan-style chocolate drink. You can also find chocolate frio as far south as Brazil and Argentina as well as in the Caribbean locales of Puerto Rico and Cuba. In fact, it's one of the featured exhibits and tasting opportunities in Havana's Museo del Chocolate (where it's flavored with honey) and a recipe is included in Beverly Cox and Martin Jacobs' book "Eating Cuban."

Where can you get chocolate frio?

Chocolate frio is the type of non-alcoholic Mexican drink you can make at home fairly easily, but it is also possible to find the drink, or something fairly similar, at certain restaurants and cafes. At one point, even Taco Bell was testing a Mexican chocolate iced coffee that seemed to have been inspired by chocolate frio.

Restaurants that offer chocolate frio on the menu tend to be found in cities with a large Hispanic population, although the restaurants themselves span the diaspora. In New York, you will find it on the menu at El Justine, a Mexican restaurant in the Bronx as well as at Colombian Arepa Express in Midtown Manhattan. Miami Beach's Varandas Brazil Grill offers this drink as well, as does Ciboney Cuban Restaurant in Miami Lakes, the Colombian Marta's Courthouse Cafe in Miami, and the Venezuelan Caffe Gourmet in Fort Lauderdale. Out on the west coast, look for chocolate frio at the Mexican Restaurante El Gordo.