14 Types Of Green Tea And What Makes Them Different

It seems green tea has become synonymous with health: matcha salons, TikTok "That Girls" hitting the 6 a.m. mindful workout, and yogis sipping on quietly steaming cups of mellow green brews. But really, green tea is nothing new. Green tea was first cultivated during the Han Dynasty of China as a medicinal beverage, and then grew to be enjoyed recreationally a few centuries later (via Art of Tea). While green tea was first cultivated in China (at least, per recorded history), it has long held significance in Southeast Asia and surrounding areas. Notably, Japan has become one of the largest consumers of green tea, if not the largest (via Marukyu Koyamaen).

While tea was long loved in the West and a major component of early global trade, green tea wasn't introduced en masse until much later because of how it is structurally (per Art of Tea). Unlike other teas, green tea is unoxidized. This means that green tea leaves are picked fresh and then cooked before they begin to dry, thus preserving their color, chlorophyll, and antioxidants, among many other goodies. Despite these overarching benefits, green teas can be distinguished by how caffeinated they are, their sweetness or bitterness, and their texture, among other factors.

Here are 14 types of green tea and what makes each of them unique.

Matcha

Bright and beautiful, matcha has recently come into the Western vernacular, but has long been at the center of Japanese tea culture as a daily drink, at breakfast or accompanying a meal (via Umami Insider). Matcha holds its place as one of the many green teas that have been cultivated in Japan. In its history spanning thousands of years, this green tea has moved from religious use to a symbol of the upper class (via Mizuba Tea). Nowadays, it finds global footing as a versatile ingredient. The tea's bright green color that is contrasted by its mellow earthy flavor makes for a one-of-a-kind ingredient.

The process of making matcha might be a slightly different experience for those unaccustomed to it. Matcha is a high-grade green tea that is sourced from shade-grown Camellia sinensis plants. This particular cultivation method ups the leaves' chlorophyll content, and makes for a more flavorful — and greener – green tea (via Teatulia). Young leaves are harvested in spring, steamed within a few hours of harvest to prevent oxidation, and then stone-ground into a powder. To drink matcha, this powder is whisked into steeping hot water and served as that familiar bright green beverage. Compared to other teas, because of both its form and structure, matcha's caffeine content is much higher. Matcha also makes a helluva good dessert, where it mellows out otherwise sweet treats like mochi.

Bi luo chun

While Japan has become well-known for its green tea, Chinese cuisine and culture also played a major role in green tea's development. Bi luo chun is among the most popular teas to this date in China, an impressive feat considering the tea's history spanning well over a hundred years (via Oriarm). The name bi luo chun roughly translates to "green snail spring," in poetic reference to the tea's dark green, almost turquoise color, the snail-shell shape its leaves are rolled into, and when it is harvested (per Tea Vivre). Bi luo chan was originally harvested in the Dongting mountains and other eastern parts of China like Wu Xian and Jiangsu, but has since become more widespread.

Bi luo chan has a bright color and mellow taste with an amazing aroma. The bi luo chan tea variety is so fragrant, in fact, that it was at one point referred to as frighteningly fragrant in ancient China (per Oriarm). Others refer to its taste as refreshing, sweet, and subtle. While the tea is said to aid in digestion and even weight loss, it also makes for a good cuppa, for those who are looking for nothing more than a warm drink.

Jasmine

Not a green tea on its own, jasmine tea more often than not uses a green tea base while the jasmine flower build the tea's aroma. While technically a scented tea, there's a lot to consider here. Most people describe the flower's scent as floral, rich, intense, sweet, and even sensual (via the Harlem Candle Company). In terms of culinary use, jasmine does not really do much beyond its aroma. Dried jasmine flowers retain very little (if any) of the flower's aroma, and have a very bitter taste (via Red Blossom Tea). Hence, herbal jasmine teas tend to be rare. Most of the time, jasmine scent is used to complement another tea, typically green tea.

Making jasmine tea usually requires combining jasmine blossoms or oil with a green tea base, as described by Sencha Tea Bar. Jasmine tea often uses spring harvested green tea leaves that are then dried and exposed to jasmine flowers, traditionally for a few months. Jasmine tea has the same caffeine concentration as its green tea base. Some say that despite its caffeine, jasmine tea aids in sleep, but as Verywell Fit argues, the simple ritual of a cup of tea, quietness, and calmness may be the real secret behind the tea's alleged sleep-inducing properties.

Funmatsucha

Similar to matcha, funmatsucha is a powdered green tea, but that's where the similarities end. Well, that and the fact the teas are almost virtually indistinguishable from each other. To most, matcha and funmatsucha look completely the same, but they couldn't be more different from each other in process, price, and palate.

The name funmatsu-cha, or simplified to funmatsucha, literally translates to "powdered tea" (via Nakaeon). For coffee lovers, it might help to understand funmatsucha as the instant coffee of the green tea world. Funnatsucha is typically made from pulverized sencha or hōjicha roasted green tea leaves, as described by My Japanese Green Tea. Funmatsucha is often stirred directly into piping hot cups of water, and can be found in many grocery stores and cafés. They are relatively affordable, as opposed to the more expensive tencha leaves.

However, unlike the sweet and delicate tencha-based matcha, funmatsucha tends to be bitter and astringent. It also lacks chlorophyll and chlorophyll-based benefits such as the amino acid L-theanine. In layman's terms, funmatsucha is more bitter than the relatively mellow matcha, and doesn't quite have the same health benefits. That said, it does have an abundance of EGCG, a powerful antioxidant.

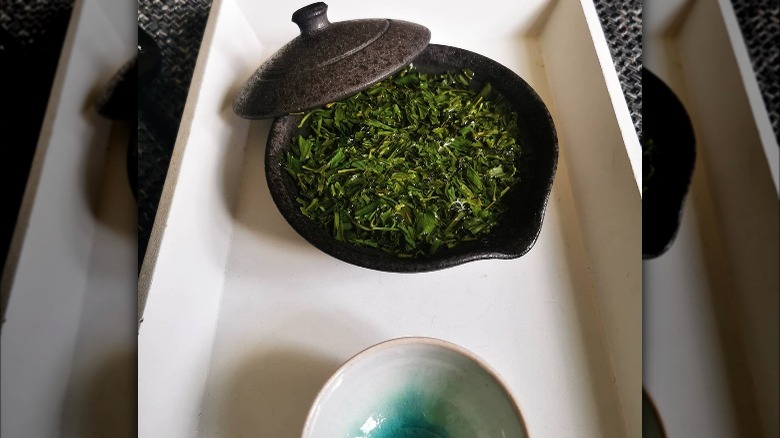

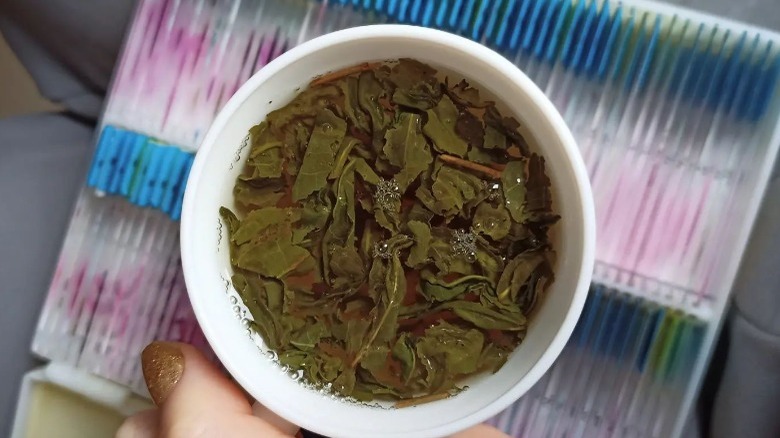

Tencha

Not only is tencha used to make matcha, but its leaves can be enjoyed just as well. Just like matcha, it lies on the other side of the price spectrum from funmatsucha. Tencha leaves are selected with a very discerning eye; since only top-quality tencha leaves can be brewed into green tea, the price reflects this fact. This isn't merely for the sake of exclusivity: As Hibiki-an observed, "And unlike Gyokuro or Sencha, it is not easy to extract the flavor from Tencha during the brewing process. Only high grade or highest grade Tencha can brew flavorfully in water."

Unsurprisingly, tencha leaves share a few similarities with matcha powder, with a sweet aroma and a distinct taste. When not made into matcha powder, tencha is typically served as a whole leaf to maintain the flavors. Tencha is also made from the same tea plant variety that is used to make the extremely pricey gyokuru tea (per the Japanese Greentea Company). Unlike gyokuru tea leaves, tencha leaves are harvested at a more advanced age, and must be brewed whole to produce a full-bodied green tea. Tencha tea leaves tend to float, so make sure to press them down or add more tea leaves to the mix.

Gyokuru

Also known as "jade dew," this jewel-toned tea is among the most expensive around. Like tencha and matcha, the tea's leaves are cultivated in the shade, its chlorophyll providing a rich color, taste, and aroma. Gyokuru tea leaves are harvested from the same plant as tencha, albeit at a younger age (via the Japanese Greentea Company). However, TeaLife notes that gyokuru is actually made from a medley of different tea plant varieties that include asahi, okumidori, yamakai, and saemidori. In this case, it's really the process that makes the product. But no matter the variety, this tea is always sweet.

One other thing sets gyokuru tea apart: its supreme umami taste. Ajinomoto describes umami as one of the five basic tastes, most often attributed to cured meat, mushrooms, tomatoes, aged cheese, and so on. The term "umami" literally translates to the essence of deliciousness. While green tea in general has umami, gyokuru reportedly reigns supreme. The tea also has a distinct thickness that TeaLife describes as being broth-like, with notes of nori and seaweed.

It is advised to sip on this tea as one would consume whiskey: slowly, so as not to be overwhelmed by the flavor while fully taking in its depth.

Longjing

Known as "Dragon Well," longjing tea is not just another Chinese green tea — in fact, it is said to be a "most imitated one" (via Tea Guardian). According to Travel China Guide, longjing tea is seen as a cure all to many common ailments. That said, there are other factors that make this tea quite popular.

Longjing tea is said to embody all the general qualities of what makes green tea so good. It is powerful, dense, sharp, and slighty astringent. Longjing's aroma is slightly complex: warm and complex with hints of chestnut, baked mung beans, and a distinct bouquet flourish, as noted by Tea Guardian. Longjing tea leaves are wok-roasted, and tend to take on a certain yellowing with patches of grey once roasted. Hot water is poured over a pinch of the tea leaves, and the tea is left to infuse directly in the glass uncovered.

Bancha

Bancha is referred to as an everyday tea, with its uncomplicated nature and toasty aroma making it a classic among green tea lovers. As The Japan Store notes, this variety works well when paired with food or as an after-meal treat. Bancha is harvested starting in August and throughout the fall, after younger leaves have already been harvested for other green tea varieties like sencha. The mature bancha tea leaves are then steamed to retain flavor and brewed in full form.

Your Coffee and Tea Essentials describes bancha as "harvested later in the year around autumn" and coming from "the lower and more mature leaves of the tea plant." While bancha tea may be seen as a "low-grade" tea due to the fact it's an end-of-the-harvest treat, its straw-like aroma and earthy flavor make for a mellow cup (via Liliku Tea). Unsurprisingly, this is among the most beloved teas in Japan.

Sencha

Sencha is another beloved Japanese tea, as it makes up about 80% of all tea exported from Japan (via Grosche). It is made from the same plant as bancha, but harvested much earlier, typically around spring and summer (via Liliku Tea). Young sencha leaves make for what has been poetically described by Grosche as an "uplifting" tea. It is sweet, with a nutty yet fruity aftertaste. Sencha is one of the most popular teas in Japan, and is often enjoyed warm or iced.

Like bancha, sencha is cultivated in the sunlight. Just as shade is extremely important to the composition of many green tea varieties, sunlight can also dramatically impact select green tea varieties. Unlike gyokuru and tencha, "sunny" green tea varieties are higher in catechin and lower in caffeine. A catechin is defined by the Natural Cancer Institute as a substance that protects cells from damage and helps cell metabolism. Catechins can thus be seen as important to one's health. While it's hard to say exactly how much drinking sencha will benefit a person's health, it wouldn't hurt to incorporate it into your diet.

Genmaicha

Genmaicha has recently increased in prominence, with major buzz surrounding it both in terms of pop culture and its health benefits. This variety has become quite popular as a vegan milk tea option at many Gen Z-oriented bubble tea shops. On the other side, genmaicha has come into its own as a healthy tea option, due to a combination of green tea's general health benefits and genmaicha's own unique traits (via Healthline).

Rumor has it that genmaicha was first made by either Buddhist monks or farmers, who mixed green tea with brown rice. Genmaicha literally means "brown rice tea" (via Matcha Tea). Because of the mixture of green tea and rice, the tea served as sustenance for those who were hungry, whether they were fasting monks, impoverished farmers, or dwellers of war-torn cities. Nowadays, the tea's earthy, nutty yet sweet flavor and unique yellow color continue to attract both longtime tea enthusiasts and newbies alike.

Gunpowder

Perhaps the most intense of tea names, gunpowder tea is as feisty as it sounds. The tea is fittingly shaped into tiny pellets that "explode" in brewed water (via Verywell Fit). Gunpowder tea at its most complicated is made up of hand-harvested tea leaves that are withered, steamed, and rolled, often by hand as well. While machine-rolled gunpowder tea is common, there are also brands that still opt for hand-rolling. Gunpowder tea may have first been named in the 19th century by a British clerk, but this variety has been cultivated in China as far back as the 7th century (via Culinary Teas).

Gunpowder tea is a green tea concentrate that, once unfurled, infuses warmly into hot water. A little bit goes a long way: A 1/2 teaspoon is more than enough to fill a cup with enough leaves to provide a flavorful serving of tea. Gunpowder tea has a remarkably olive-green color. Despite its unique appearance, gunpowder tea has a sweet yet pungent flavor that is admittedly characteristic of many green tea varieties.

Hojicha

Hojicha tea is often sourced primarily from bancha leaves, though it can also be sourced from sencha leaves (via the Japanese Greentea Company). Hojicha is another Japanese green tea variety, but what distinguishes it from other varieties is the preparation that goes into it. As described by the Hojicha Company, this variety is actually roasted, usually over charcoal. Many blends also incorporate stems into their mix. Hojicha tea is said to have originated in the 1920s from the efforts of a tea merchant who sought "to make the most of the leftover leaves, stems, stalks, and twigs by roasting them over charcoal."

While hojicha is technically still classified as a green tea, its roasting process produces a liquid with a reddish-brown hue. The roasting process burns the bitterness of the otherwise astringent plant, so hojicha green tea is much sweeter and smokier than other green tea varieties. It doesn't hurt that this preparation method lends for a comforting earthy aroma. It's also because of this roasting process that this particular variety is typically made from lower grade green tea leaves.

Kukicha

Kukicha is unique in that it is sweet, creamy, and nutty, all at the same time (via Shizuo Tea). Interestingly, a cup of kukicha tea is said to contain around 13 times more calcium than milk.

Kukicha is harvested from the same plant as sencha and bencha, but unlike them, kukicha tea is prepared from stems instead of leaves. Technically, kukicha tea can be brewed from the stems of any green tea variety. As plant stems are not exposed to as much sunlight as leaves, kukicha tea tends to have a sweeter flavor compared to other green tea varieties. The green tea stems, once steamed, produce a naturally woody aroma and a pale green tea.

Kukicha tea contains significantly less caffeine than leaf-based green teas. In fact, according to Sha Wellness Clinic, kukicha tea has virtually no caffeine, which makes it perfect for any time of day (or as an alternative to one's afternoon cup of coffee). Additionally, it can work as a digestive after meals.

Konacha

Konacha is the third of the three powdered Japanese green tea varieties. While it may look like just another brew, there are a few significant things that distinguish konacha from the other two.

For starters, rather than being cultivated on its own, konacha is the natural by-product of processing "higher-end" teas like Gyokuro or Sencha (via Tealife). Once larger leaves are picked for larger batches of tea, the smaller leaves and "specks" remain. These are used as konacha powder, which tends to come at a lower price tag, yet still tastes just as vibrant as any green tea. Unlike funmatsucha and matcha, konacha is not really ground into a powder; rather, it's a collection of tiny leaves and leftover leaf matter. In fact, some even refer to konacha as tea "dust" rather than tea powder. Interestingly, konacha tea never really fully dissolves, according to Hibiki-an.

Konacha is relatively rare. Only around 10% of the tea plant can be used to make a decent powder, and thus it can be hard to find a decent blend. Konacha's relatively low price and complex flavor profile make it a favorite of sushi and unagi restaurants, which offer the tea as a palette cleanser. Here's a "bitter" note to end on, though: Konacha is much more astringent than most green tea varieties.