What American Restaurants Looked Like 100 Years Ago

It goes without saying, but 100 years ago, America looked very different from the way it looks now. World War I had ended recently, the economy was exploding (at least until the beginning of the Great Depression in 1929), and the 18th Amendment had outlawed the production of alcohol. Immigrant communities were bringing their food and culture to U.S. shores, and women had recently earned the right to vote.

All of these societal forces shaped the restaurant landscape of the 1920s. The decade was a period of dramatic change in the foodservice industry, as many businesses pivoted away from alcohol to focus on food. Some old-school restaurants couldn't keep up with the times. Many familiar types of restaurants to present-day eaters, like fast food places, diners, and cafeterias, were either born or evolved into their modern forms during this time period. Much like they had carved out a space for themselves in the political sphere, women also claimed their rightful place in the restaurant world in the 1920s. For the first time, eateries opened up that actively sought women's business. The American menu also expanded during this time, as immigrants introduced this country to a wider variety of flavors.

This is a snapshot of what the American restaurant scene was like about a century ago.

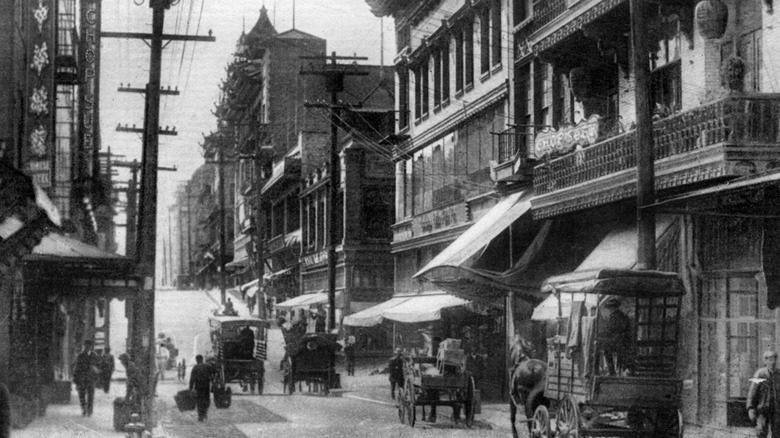

There was a Chinese restaurant boom

While American Chinese food dates back to the 1800s, it wasn't until the turn of the 20th century that it became common for Chinese restaurants in America to serve non-Chinese clientele. Per PBS, the 1906 earthquake that destroyed San Francisco's Chinatown gave Chinese American business owners an unexpected opportunity to recreate the neighborhood as a tourist attraction complete with pagoda-esque buildings. The rebrand made San Francisco Chinatown a popular destination for tourists of all kinds.

Immigration laws also increased the availability of Chinese food in America in the first few decades of the 20th century. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 prohibited most Chinese immigration to the U.S. However, an exception to the law implemented in 1915 allowed restaurant owners to bring Chinese workers to the U.S. Because of this loophole, the number of Chinese restaurants in America ballooned in the 1910s, '20s, and '30s.

The American Chinese food of this time period, especially the stuff sold to non-Chinese diners, was rather different from the Chinese food that is available today. Chinese ingredients were hard to come by in the U.S. and the flavors of the cuisine were still unfamiliar to many Americans, so improvised dishes like chop suey and egg foo yung dominated menus of the era.

So did Italian American food

Chinese food wasn't the only culinary import that gained wider acceptance around 100 years ago. As First We Feast notes, Italian food also became more popular outside of the Italian immigrant community during the 1920s. Italian American food began diverging from the food actually eaten in Italy once immigrants arrived in America in the 19th and realized that in their new country, they could afford more meat. This is when classic red-sauce Italian dishes like spaghetti and meatballs were born. However, even though this new cuisine was in many ways thoroughly American, it was still mostly eaten by Italian immigrants and their descendants. As author Simone Cinotto told First We Feast, non-Italians were put off by the assertive flavor of garlic and found Italian cuisine unfamiliar and unappealing.

Italian food received a boost in popularity during Prohibition, the period between 1920 and 1933 when it was against the law to sell alcohol in the U.S. More people outside of the Italian community began eating at Italian restaurants because they often served illegal wine. These patrons may have been lured in by the hooch, but once they were in the door, they realized the food was pretty good too.

The golden age of Jewish delis was a century ago

In his book "Pastrami on Rye: An Overstuffed History of the Jewish Deli," Ted Merwin argues that the Jewish deli came into its own as a cultural institution in the 1920s (via The World). Much like the generous portions of meat in Italian American dishes, the enormous sandwiches served up by delis symbolized the relative prosperity of the Jewish community in America. In Eastern Europe, where most Jewish immigrants to America came from, meat would have been an expensive luxury saved for special occasions.

During this period, delis were also community centers where Jewish people could congregate without having to worry about the antisemitism they may have faced in other spaces. Delis during the early part of the 20th century, at least in New York, had a certain glamor to them. The delis in New York City's theater district became well-known celebrity haunts.

Sadly, the heyday of the Jewish deli was relatively short. Per Forward, after World War II, Jewish Americans became more assimilated into U.S. culture at large, and the deli lost its prominent place as a cultural hub. You can still find them, of course, but delis aren't the luxurious hotspots that they were in the '20s and '30s.

The 1920s spawned the first fast food burger chain

A century ago, the fast food hamburger had a big moment. Burgers were already around by the 1920s, but they had a bit of an image problem; people thought of them as unhealthy and unsanitary. But that all changed in 1921 when entrepreneurs Walter Anderson and Billy Ingram decided to create a new type of burger restaurant in Wichita, Kansas. They called their fledgling business White Castle. The restaurant expanded, becoming America's first fast food chain.

Perhaps even more importantly, White Castle ignited Americans' love affair with burgers. By marketing itself as hygienic and healthy, White Castle made the public much less suspicious of burgers. This chain, more than any other, is the reason that burgers are synonymous with fast food. Later, larger chains like McDonald's, Burger King, and Wendy's all have White Castle to thank.

Of course, White Castle wasn't the same in the 1920s as it is in the 2020s. 100 years ago, the burgers were made with balls of fresh beef griddled smashburger style, not the steamed, perforated, frozen patties the chain uses today.

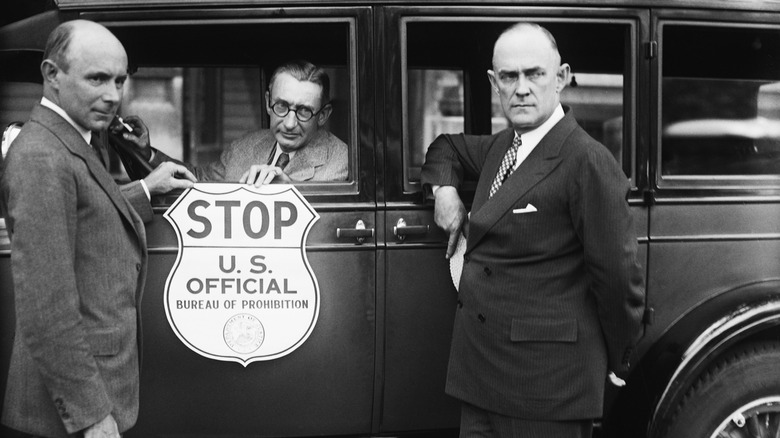

Prohibition impacted the restaurant industry

While Prohibition may have been a boon for Italian restaurants that got away with selling wine under the table, for the restaurant industry at large, the ban on alcoholic beverage sales was a significant disruption, per Restaurant Business. Pre-Prohibition, alcohol was one of the main profit drivers for many restaurants, and now that alcohol was illegal, business owners were forced to pivot to food-first business models.

Not all restaurants survived the change. Per Gothamist, Delmonico's, the New York City restaurant that pioneered American fine dining and originated such classic dishes as baked Alaska, Lobster Newburg, and Eggs Benedict, was one such Prohibition victim. Despite earning accolades nationwide since its founding in 1837, the original Delmonico's found it impossible to do business without selling alcohol and closed its doors in 1923. Another restaurant with the same name opened in the same location in 1929, but it was a new business unaffiliated with the family that originally ran Delmonico's.

Delmonico's struggles notwithstanding, the '20s were generally a prosperous time for the American restaurant industry. Restaurant Business notes that restaurants were the second most common type of business in America during the decade, surpassed only by retail stores. However, when the stock market tanked in 1929, sparking the Great Depression, restaurants fell on harder times.

The Waldorf-Astoria was one of the grandest eateries

Prohibition might have been tough for some fine dining palaces, but for others, the post-World War I decade was a golden era. The restaurant in the Waldorf-Astoria hotel was known for serving incredibly luxurious cuisine during the tenure of Chef Oscar Tschirky, per Loyola University. The restaurant's dining room looked just as fancy as the food, with elaborate carvings on the walls, white tablecloths, and intricate murals.

A sample Waldorf-Astoria menu from 1919 published by the New York Public Library shows an elaborate multi-course dinner of heavy, French-influenced dishes followed by dessert, cigars, and coffee. Some dishes, like chicken gumbo, are familiar today, though not in the form served by Tschirky. Others, like cooked cucumbers in cream sauce, are pretty hard to find in the 21st century.

Tschirky worked at the Waldorf-Astoria for almost the whole first half of the 20th century, staying with the hotel when it moved to an even larger, fancier building in 1931. The hotel's other food-related claim to fame from this era was that it invented room service.

Speakeasies also served food

When we think of speakeasies we imagine rough-and-tumble underground gin joints serving liquor and not much else. However, anybody who's ever gone out for a late, boozy night knows that the munchies will inevitably strike at some point. You need some carbs, fat, and calories to soak up the poison. Speakeasy operators served this need by offering food, frequently in the form of finger sandwiches or canapés, per PBS.

Speakeasies were often informal operations run out of basements or the houses of everyday people. Serving food helped keep patrons from becoming noticeably drunk, which could have blown the speakeasy's cover if the authorities noticed. While simple handheld appetizers were the most common foods served at speakeasies, some establishments had much more elaborate food service programs. According to History, New York's 21 Club, a massive speakeasy that served the most well-heeled denizens of its home city, had two whole dining rooms in addition to a dancing area, multiple bars, and a wine cellar.

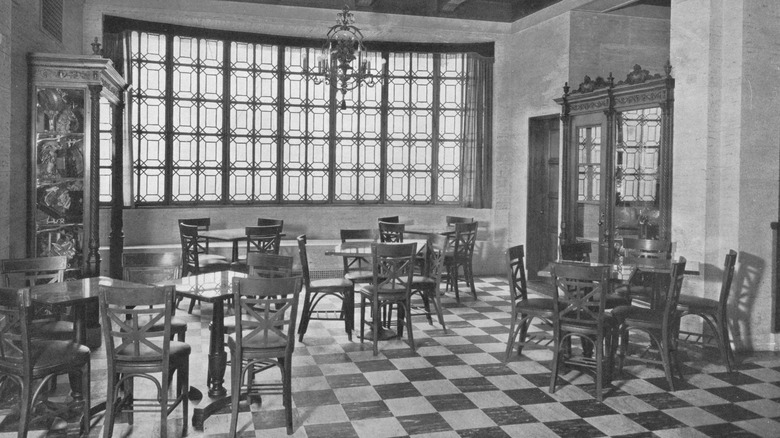

Cafeterias were all the rage

While speakeasies catered to Americans' unquenchable thirst for alcohol, another, much more family-friendly trend took hold in the U.S. during the same time period: cafeterias. According to Restaurant-ing Through History, in the 1920s, cafeterias overtook old-school European-style fine dining restaurants. The new cafeterias didn't require tipping because they were self-serve. They sold homey American food instead of elaborate Haute French dishes.

Los Angeles was cafeteria ground zero. The first example of what we think of as a cafeteria today — a restaurant where you slide a tray down a rail, picking food that's displayed in a line — opened in downtown L.A. in 1905, according to the Los Angeles Times. Helen Mosher founded this original cafeteria, but the idea really caught on when the Boos Brothers opened a copycat restaurant a few blocks away. The brothers' restaurant was successful enough to expand into a small chain. By the 1920s, the L.A.-style cafeteria was popular nationwide.

While cafeterias of this era were more humble than the fine dining restaurants they replaced, they were often much fancier than today's cafeterias. Some cafeterias were decorated in grand Art Deco style, and patrons would dress in formalwear to dine in them.

You could get a hot meal from a vending machine

The touchscreen ordering interfaces being phased in by some fast food restaurants might seem like the height of 21st-century technology, but automated eating has been around much longer than you might think. In the first decades of the 20th century, the world's biggest restaurant chain was basically an elaborate vending machine for hot food.

Per History, Horn & Hardart Automats, as they were called, debuted in Philadelphia in 1902. In some ways, they represented an extreme version of the self-service cafeteria model. Patrons would walk in and approach a massive wall of cubbies with coin slots, insert a nickel, and be rewarded with freshly prepared food. Horn & Hardart reached its height of popularity during the Great Depression when the chain's convenience and low prices were a perfect fit for the stretched budget of the average urban dweller.

At its best, the Automat system worked like magic, delivering high-quality scratch-made food to diners in a hyper-efficient way. However, the business model struggled to keep up with inflation and suburbanization in the 1950s, and by 1991, no Horn & Hardart remained open.

The classic American diner emerged during this time

The stereotypical diner — stainless steel exterior, checkerboard floor, Formica counters, and a glass case of pie — came into being a long time ago, but that's not how diners originally looked. In fact, as Smithsonian Magazine notes, when the first diner came on the scene in 1872, it looked a lot more like what we would call a food truck. In the late 1800s, mobile restaurants on wheels started selling food late at night after most other eateries had closed. Over time, these "dining cars," as they were known, became more elaborate, incorporating inside seating and eventually losing their wheels and turning into stationary business. The name was shortened to "diner" in the mid-'20s.

Although diners stopped being mobile, they retained one aspect of their "dining car" origins — they were built in factories and then shipped in their entirety to their final resting spots. Per Paste, the classic chrome look we associate with diners today is a product of the 1930s, when diners were trying to shed their rough reputation and advertise themselves as modern and sleek.

Women enjoyed dining out at places like Schrafft's

According to JSTOR Daily, in the 1800s, most restaurants were patronized by male diners. Eateries either banned women outright or only allowed them to eat if they came with a man. What's more, as Restaurant-ing Through History recounts, that male dominance extended to restaurant staff as well, who were mostly men. That started to change in the 1920s, as more women began working in the food service industry. Some establishments with female employees also catered to a primarily female clientele, giving women a safe and friendly space to eat alone or without male company. Schrafft's, a chain of restaurants that began as a candy business, was one of the most notable of these spots.

Schrafft's grew throughout the first decades of the 20th century, expanding to nearly two dozen stores by 1923, per Brownstoner. The chain served upscale light lunch dishes in a classy environment. In a rarity for the time, the company hired women not just as waitresses, but as managers too.

Schrafft's continued to expand until the '60s, but as time went on, its strengths turned into weaknesses. It could no longer survive as a restaurant that primarily catered to women, and it struggled to retool its image to attract more male customers. Per West Side Rag, the last Schrafft's closed its doors in 1984.

Tea rooms attracted female diners and a Bohemian crowd

Chain restaurants like Schrafft's weren't the only early 20th century restaurants that employed and served women. Tea rooms were also incredibly popular around 100 years ago. Per JSTOR Daily, the vast majority of American tea rooms were operated by female entrepreneurs. In a time when employment options for women were limited, owning a tea room was one of the best ways for a woman to make her own money. As Jan Whitaker explains in "Tea at the Blue Lantern Inn," "During the 1920s, at the height of the tea room craze, these little businesses were virtually synonymous with female self-expression." Tea rooms served food like salads, light sandwiches, and pastries rather than heavy, meat-centric dishes. They were quite popular during Prohibition, and tea rooms were associated with the anti-alcohol Temperance movement. Like Schrafft's, tea rooms were spaces where women could exist in public in a welcoming environment whether or not they had a man with them.

Besides independent women, tea rooms had another group of fans: artsy Bohemians. In New York's West Village, elaborately-decorated, eccentric tea rooms acted as clubhouses for patrons with an alternative bent.