30 Types Of Bread And What Makes Them Unique

Few things can inspire as much enthusiasm as good bread. From the heavenly smell of it baking, to the delicious end results, people love bread. This is not a new phenomenon, considering humans have been enjoying bread for over 14,000 years.

Typically made of a simple mixture of wheat flour, salt, water, and yeast, bread is a way to transform fields of grains into a nutritious, digestible, easy to eat, and tasty mainstay of many diets. As Bon Appetit explains, many languages have conflated the words for "bread" and "life," in part because the two concepts were so closely related; bread literally was the one thing keeping many people alive on their bare bones subsistence diet.

One great thing about bread is the huge range of styles and types. Many of these are regional specialties that reflect the local culture and circumstances of where it comes from — it's hard to picture French food without a baguette, just as it's impossible to think of Mexican food without tortillas. In this piece we will take a world tour and cover 30 different types of bread from all different corners of the globe. Each one has a story to tell and each one can be absolutely delicious and satisfying.

French bread

French bread inevitably brings to mind a long, thin baguette (probably being held by someone smoking a cigarette and wearing a beret...), and this is in fact, a perfect example of this type of bread. French bread is generally made of white wheat flour and is extremely perishable, notes Delighted Cooking. In fact, most reputable bakeries make baguettes several times a day so that no customer needs to buy a stale baguette.

One noteworthy aspect of this bread is the lack of any enrichment; there is no fat, no milk, nothing extraneous. Just flour, water, yeast, and salt. Because this formula is so simple, it requires a good bit of expertise to get just right. Julia Child's staggering, 22-page recipe for French Bread in the second volume of her magnum opus "Mastering the Art of French Cooking" proves the point (via American History Museum). It is not a set of instructions for the faint of heart.

This type of bread was the main source of nourishment for the working class and — as the availability plummeted and price soared — it became one of the primary motivating factors for the French Revolution. In fact, the ultimately false tale of Marie Antoinette saying "let them eat cake" was supposedly in reference to her hearing about how difficult it was for poor citizens to afford bread. The lesson is, perhaps, don't come between a hungry Frenchman and his baguette.

Focaccia

Focaccia is on the other end of the spectrum; where French bread is lean and straightforward, the best focaccia is loaded with flavorful olive oil that provides for a rich, crispy treat. It is normally made as a flat, relatively thin sheet. As La Cucina Italiana explains, soft dough is dimpled by the baker's fingertips and these wells are merely more channels for more olive oil.

The Italian region of Liguria, in the northwest of the country, bordering the Mediterranean Sea, claims to make the best version of focaccia — the local olive oil, which Ligurians tout as the best in Italy, certainly does no harm. This abundance of oil in the bread makes for a crisp, rich mouthfeel that enthusiasts can't get enough of. Chef Samin Nosrat made a name for herself when she released her book "Fat, Salt, Acid, Heat" in 2017. This book sought to break down cooking to fundamental, elemental parts. For the chapter on fat and how it works in the kitchen, focaccia was chosen as the perfect way to illustrate its importance, to delicious results (via the Kitchn).

Some enterprising bakers like to add extras to the tops of their focaccia. This can include everything from a simple scattering of chopped rosemary to an elaborate landscape made out of vegetables like onions, tomatoes, and zucchini. Additions such as these can make a focaccia practically an entire meal unto itself.

Sourdough

Sourdough is something that's unique among all these different types of bread. Almost all recipes for bread rely on commercially available yeast for leavening — which is what gives bread its lightness. Instead of that more reliable and consistent method, sourdough uses a technique where the baker takes advantage of the naturally occurring wild yeasts that live all around us. These yeasts are harnessed by way of a starter — essentially a mix of flour and water that is left out at room temperature — which is highly attractive and nutritious for these wild yeasts.

Recently, due to COVID-related stay-at-home orders, sourdough has been having a bit of a moment. Thanks to ample time at home and not a lot of other options, Americans turned to sourdough as much as a project to occupy time as a source of delicious bread.

Thanks to the natural, "wild" flavors in these homegrown yeasts, sourdough has a tangy, sour flavor that adds complexity and that devotees can't stop eating. Certain locations, such as San Francisco are famous for the quality of their sourdough, something locals claim is due to the naturally occurring microbes that just happen to exist there, as noted in Discover Magazine.

Brioche

Although, as previously mentioned, Marie Antoinette did not in fact say "Let them eat cake," the actual quote she is meant to have said was "Let them eat brioche." This is an understandable mistranslation since brioche is a bread that is so rich with eggs and butter that it is practically a cake.

As noted by Serious Eats, brioche is a classic example of what is referred to as an enriched dough, meaning the bare bones recipe of flour, yeast, salt, and water is extended by ingredients such as milk, eggs, sugar, or butter. While this makes the finished product delicious and often gives a plush, rich texture, these additions can slow down the process of the yeast, which makes these types of breads a little trickier to make.

This golden loaf comes in a few different classic shapes and probably the most famous is the brioche à tête, which comes as a large round loaf with another, smaller round perched atop. This gets baked in a round, fluted pan and is often served for breakfast in its native France, complete with additional butter and jam. Brioche is also a popular ingredient in particularly luxe versions of things like bread pudding or French toast. Here, the rich bread adds a level of indulgence to otherwise simple dishes.

Challah

Another enriched dough, challah is a traditional Jewish specialty. Because of faith-based dietary restrictions which stipulate that milk cannot be consumed on the same table as meat, this bread contains no butter, but the large amount of egg yolks lends a beautiful, golden color and a rich taste.

Challah is an expected accompaniment to Jewish religious celebrations and, as My Jewish Learning explains, there is a great deal of symbolism and significance associated with this is eggy bread. Everything from the number of loaves served, to the white napkin that is usually draped over is loaded with meaning harkening back to the Jewish cultural and religious heritage.

This bread is often braided into elaborate plaits and the outside is usually brushed with more egg yolk. This gives a burnished, beautiful exterior that hides a soft, pale yellow crumb inside. This is another candidate for bread-based dishes to provide added flavor and richness, and challah French toast is something of a modern classic.

Pain de mie

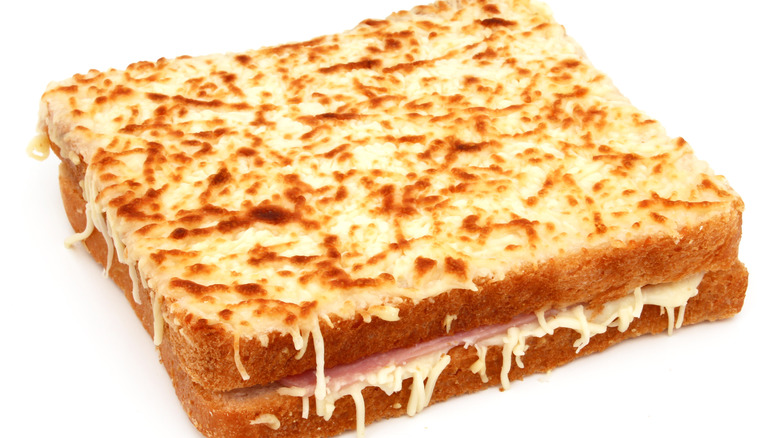

Pain de mie is a French creation. It is a soft bread, made of white wheat flour and it is notable for its texture, its lack of a crust, and the special pan it is baked in. This is a bread that is typically used for things like canapes or croutons for hors d'oeuvres. The name translates to "crumb bread" because the emphasis is not on the outside crust, but on the soft texture of the interior — which professional bakers call the "crumb" of the bread, according to C-Cell.

The texture of pain de mie is soft but somewhat dense — a consequence of including some amount of shortening or oil, according to Taste Atlas. This allows the bread to serve as a neutral, sturdy background for any number of toppings and fillings. The classic French bistro sandwich the croque monsieur (basically a grilled ham and cheese) is usually served on this type of bread.

The pan that pain de mie bakes in is rectangular-shaped with sharp edges and it comes with a tight-fitting lid. This means the bread can't rise up too high and makes for a square, squat loaf. This pan is usually called a Pullman pan in the U.S. and this type of bread is often called a Pullman loaf.

Naan

A traditional Indian flatbread with a very long, complex history, naan is a staple for millions of people the world over. Although primarily associated with India, the word is actually of Persian origin, where it refers to any type of bread, not just this specific, flat variety. In India, naan is served alongside many of the complex, spicy stews that make up the cuisine. The somewhat bland bread is a perfect backdrop for the richly flavored dishes that lovers of Indian food appreciate. Often, a piece of naan will be used to scrape a plate or a bowl clean.

Although naan can be confused with roti – another Indian flatbread — the main thing to remember is that roti is quite flat, like a tortilla, whereas naan is much puffier and thicker. Part of this comes down to regional variation, with Northern regions being much more partial to the inclusion of flat bread with their meals.

As Indian Express explains, this bread was once the sole domain of royalty, but as standards of living have continuously improved across the nation, more and more people have gotten access to the resources and the technical know-how to be able to provide this small luxury to themselves.

Rye

Rye bread is something that is familiar to anyone who frequents Jewish delis or American diners. It's as familiar filled with pastrami and mustard as it is escorting a plate of bacon and eggs. Often it comes flecked with caraway seeds and many people have come to expect them as part of the package.

Rye actually refers to the type of flour used to make this bread. It is a grass that can behave somewhat like wheat, but with a darker, spicier flavor. Usually, according to the Spruce Eats, some amount of wheat flour is included in a rye loaf to ensure enough gluten development so that the finished product has enough structure to hold itself up. This is a European specialty and it is often paired with beets, dill, vinegar, and garlic. This tradition was brought to the U.S. by Jewish immigrants who wanted to preserve their cultural heritage in their new home.

In case the flavor and texture isn't enough of a selling point, some people tout the nutritional benefits of rye bread, since, as noted by Healthline, the flour from rye is rich in many vitamins and nutrients.

Pumpernickel

This is a dark bread with a silly name. As HuffPost points out, in German it translates into something like "devil fart" because it's thought to be so coarse that it would even cause Lucifer some indigestion. The intense, dark color of pumpernickel can often make for a striking presentation. Traditionally this bread is made with a sourdough starter, but modern bakers often use the much more reliable commercial yeast.

Similar to rye bread, this loaf — also native to central Europe — seems to have an affinity for pickle-y pungent flavors like sauerkraut or mustard. Some enterprising cooks will use pumpernickel bread to make croutons for dishes that contain some of these ingredients.

As German Food Guide explains, this dark bread is a specialty of the western German province of Westphalia. In order to soften the hard rye flour that traditionally makes up pumpernickel, it used to need to be steamed for hours. But these days some shortcuts can be taken. One of these is the inclusion of red beet syrup which adds to the color and provides some sweetness that can cut through the sometimes bitter loaf.

Panettone

Panettone is an Italian holiday bread. It is usually enriched with sugar, eggs, and butter. Typically it is also studded with dried fruit such as raisins or candied citrus peel. For many Italians, the shape, tall, narrow and puffy, is a sure sign that Christmas is on the way. This loaf usually comes in a paper liner that looks somewhat like a giant cupcake liner.

According to the BBC, panettone is closely associated with the northern Italian city of Milan, where top notch bakeries compete to see who has the most lavish window display. These displays are always crowned by the tall, distinctive shape of a panettone, whose golden color and jewel-like studs of fruit make for a stunning sight. Because of how rich the dough is, making a panettone is the work of several days; as noted by La Cucina Italiana, the additions of butter and sugar slow down the yeast significantly. This means that it usually needs an overnight rest in the refrigerator in order to achieve its full height and proper fluffiness.

This is a particularly old loaf, with origins that stretch back to the 15th century. Italian bakers have had plenty of time to perfect this holiday treat and its enduring popularity the world over proves that their effort was not in vain.

Ciabatta

This oblong, relatively flat bread is named after the Italian word for slipper. This refers to both the shape and the soft, pillowy inside. One of the hallmarks of this bread is its open, irregular crumb structure that has big, open bubbles inside. This comes from having a relatively wet dough that has a high level of hydration — or ratio of water to flour, as noted by Bricco Salumeria.

Ciabatta is a relative newcomer, having been invented in the 1980s as a different take on a French baguette with an Italian twist. The style caught on and remains very popular to this day. As Abigail's Bakery explains, this bread is particularly popular for the hot, pressed Italian sandwiches called panini. The crisp crust of ciabatta is perfect when toasted on a panini press and the crackling outside makes a satisfying crunch around the sandwich filling.

Per Foods Guy, the flavor of ciabatta is somewhat mild and the main selling point is the texture. The crisp crust with the chewy inside is a bread lover's dream. Another way to exploit that texture is to make this elongated loaf into garlic bread, saturating the open crumb with a flavorful garlic butter mixture and baking till crisp and fragrant.

Milk bread

The Japanese have a habit of taking ordinary things and bringing them to the limits of perfection. One place where it is evident is the making of their famous milk bread. As Bon Appetit notes, the soft, cottony, melt-in-your-mouth loaf has a whisper of a crust because it's all about the tender interior.

The Japanese term for this loaf is shokupan. This actually comes from the European form of bread, which across many languages is usually some form of the word "pan," according to Japan Times. This word comes from the Portuguese word for bread. (As Epicurus explains, merchants and missionaries from Portugal first arrived to the island nation in the 1500s.)

According to Healthy Nibbles and Bits, one way the Japanese — particularly children — consume this bread is toasted and drizzled with condensed milk. This doubling down on the milk makes for a soft, creamy treat that underscores the dairy flavor and makes butter superfluous (although there is almost certainly plenty that went into making the loaf in the first place).

White bread

Although any bread made with white flour can technically be called "white bread," the phrase brings to mind a very specific loaf. That is the American-style, soft, sweet, and bland. This type of bread is packed with preservatives and stabilizers which keep it from becoming stale for weeks.

According to NPR, the pre-sliced, shelf stable marvel that we know today was first pioneered in Missouri in 1928. This was a symbol of modern innovation at the time, although it did spark a backlash from people concerned that industrialization was separating people from natural, healthy food and nutrition. That type of controversy has not entirely disappeared to this day. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration today relies on companies to police themselves about the safety of ingredients that they add to their products. In the European Unions and in other countries such as Brazil and China, governments have outlawed some of the signature additives to American white bread that give it such a long shelf-life, as noted in the Guardian.

This type of bread has become so associated with the image of post WWII American suburban conformity that it has become a slang word that means boring or plain. Referring to something as "white bread" conveys a very clear image of cookie cutter, 1950s blandness.

Whole Wheat

Whole wheat bread refers to bread that has been made using flour milled from wheat that wasn't stripped of its outer bran and germ coating. This coating contains most of the nutrients in a stalk of wheat and removing it leaves behind a blander, whiter result.

What's left is the inner part called the endosperm, which is largely made of starches and sugars, and has almost none of the beneficial vitamins and nutrients that whole wheat provides. There is a tradeoff, however. The outer layers that are stripped away are much more perishable than the inner endosperm. That means whole wheat flour doesn't last as long as white flour. For this reason many large scale food operations only keep white flour on hand for long term storage.

Whole wheat bread usually has a coarser texture and a more rustic, nuttier flavor. The roughness of the whole wheat flour translates to a denser, less pillowy interior, as noted by Smithsonian Magazine. Many recipes for whole wheat bread contain some measure of white flour in order to alleviate this problem. Other solutions include adding some form of acid — such as buttermilk — that tenderizes the whole wheat flour and contributes to a softer, lighter loaf.

Pita

Pita is one of the oldest breads in existence. There is evidence that pita has been made in the Fertile Crescent of Mesopotamia for the past 15,000 years. This has spread all over the Middle East and many individual areas and countries put their own spin on this ancient food. Pita is a leavened flatbread which, thanks to the specific way it's made, develops a hollow center. It makes for an ideal container to stuff with tasty treats like falafel or gyro meat. Thanks to a very hot oven, the steam in the uncooked dough evaporates and puffs up, leaving a pocket that is just begging to be filled with something delicious.

One particularly popular use of pita is as a dip for various Middle Eastern specialities. This includes things like hummus and the eggplant-based spread of baba ghanoush. Things like seasoning blends, including the famous za'atar mix — a lively blend of dried herbs, spices, sesame seed, and tart sumac — can often add to a plain pita and make it that much more interesting to eat.

Although it seems intimidating, it is perfectly possible to make pita at home. In doing so you can avoid the store bought kind which are often loaded with preservatives to extend their shelf life.

Bagels

Bagels, with their signature ring shape, are a mainstay of American breakfast joints, but as the Atlantic notes, their origins stretch back over six centuries. It's believed the bagel was first invented in Poland, and the baked good eventually made its way across the pond when Jewish immigrants relocated to the United States.

New York has become particularly associated with the bagel. Some point to the quality of the local water as the reason the bagels in the Big Apple are so superior, but as NPR explains, it has much more to do with the method of boiling the bagels before they are baked. This allows the structure to be set before it's put into the oven and contributes to the signature chewy texture.

Another consistent part of bagel making is the inclusion of malt syrup. This sweetener, made of malted barley, adds nuttiness and complexity to bagels and contributes a golden brown color that enthusiasts expect. One famous way of eating this Jewish deli classic is with a smear of cream cheese and topped with smoked fish. Accompaniments like capers, dill, sliced onion, and black pepper all add to this delicious treat.

Fougasse

Fousgasse sometimes gets unfairly compared to the much better known Italian focaccia. This comparison is probably inevitable since both are Mediterranean-based chewy, rustic breads enriched with olive oil. However, as Bon Appetit explains, focaccia is typically baked in neat rectangular shapes and is cut into squares. Meanwhile, fougasse is shaped free form and usually arrives at the table whole, in all its glory.

This bread is often leaf shaped, with slashes cut into it so it fans out and presents a dramatic presentation. That drama is typically assisted by the various toppings that get put on top of a fougasse before it's baked. Since it comes from the sun-drenched Provence on the Mediterranean coast, these additions are usually local specialties like olives, onions, herbs, and anchovies.

A sweet version of fougasse, made with butter and flavored with orange flower water, is also a traditional option. This versatility shows off why this bread, with roots in ancient Rome, remains popular to this day.

Injera

Injera is an Ethiopian specialty, and the flat, spongy bread plays a huge role in that nation's food culture since it acts as a reliable and ubiquitous sponge to soak up the lavishly spiced stews that characterize it. This does not make injera a total blank canvas, however. This flatbread has a unique character all its own.

Part of that character comes from the grain that is milled to make it. Called teff, it is an ancient source of nutrition; as Britannica points out, it has been cultivated for thousands of years in Ethiopia. It comes in different grades of darkness, but as Daring Gourmet notes, the darkest version will yield the most authentic experience.

The other component of its flavoring comes from the fermentation process. Similar to sourdough, injera batter is allowed to pick up wild yeasts that add a sour, complex flavor to the finished product. According to The Toronto Star, this batter is cooked flat on a griddle so that it resembles a spongy crepe. Wild Junket explains that the flavor can be off-putting for neophytes and is best appreciated as a component to a traditional Ethiopian meal, where it fits into the overall harmony of the experience.

Soda bread

Soda bread is something of a misnomer. Traditional bread is leavened with yeast and has a relatively light, open interior. As the name implies, soda bread gets its lift from the inclusion of baking soda. The texture that this gives is closer to a biscuit than a true bread, but this Irish classic is still delicious, no matter what you call it. Typically lightly sweetened and studded with raisins, soda bread is particularly delicious when smeared with butter and eaten as a snack, but some people serve it as an accompaniment to main course stews and roasts, sort of like a giant dinner roll.

In the U.S., soda bread usually gets served as part of a Saint Patrick's day celebration, right alongside the Guinness and corned beef and cabbage. The rest of the year is also a fine time for serving this simple bread; thanks to its lack of yeast, it doesn't require any of the lengthy proofing or rising steps that more typical breads do.

Another thing particular to soda bread is how it is baked without a pan, just shaped on a flat sheet and slid into the oven. This means you need to start with a particularly stiff dough so it will keep its shape as it is formed and baked. According to Taste of Home, to offset this, buttermilk is often included since it lends moisture and tenderness when it is used.

Parker House rolls

Named after one of the most famous inns in the U.S., Parker House rolls are native to the establishment of the same name in Boston, Massachusetts. This was not the only noteworthy dish created at this establishment: According to Foodicles, the iconic Boston Cream Pie was also invented here.

The style, enriched with butter, milk, and a small amount of sugar, has proved popular to this day and a basket of buttery rolls on the table is a holiday tradition for many American families. The compact size makes them great to serve on a crowded buffet, where the tiny roll will take up very little precious real estate on an eater's plate. They reached a wider audience when Fannie Farmer included a recipe for them in her iconic "Boston Cooking School Book" published in 1896, according to Boston Magazine. This important cookbook taught a generation of Americans how to cook and took the anachronistic step of including scientific information about how cooking worked.

Although they are an old-fashioned dinner accompaniment, they have gained new cache, as innovative chefs riff on the classic and put their own stamp on it, according to Bloomberg. These twists include things like adding flavored butters or other fats and baking in a wood burning oven to get a slightly smoky flavor.

Pretzels

Although most people probably think of pretzels as a crunchy, salty snack, they have a wide range of textures and many of them are light and fluffy. These beloved, salty treats come from the Bavarian region in southern Germany. Many of the stereotypes that Americans associate with Germans — think Lederhosen and Oktoberfest — come from this historic region, and a plate of pretzels served with a spicy mustard definitely fits that bill.

Pretzels are noteworthy for their almost shellacked exterior, usually studded with coarse salt. As noted by King Arthur Baking Company, this deeply browned exterior originally came from a dip in a lye solution. Although professional bakeries may still use this technique, rather than mess around with a caustic chemical, home bakers are encouraged to use a baking soda solution. The alkaline properties of dissolved baking soda mimic the effect the lye has on the dough.

The distinctive shape is said to resemble crossed hands at prayer, and as The New York Times recounted, some historians believe that they were invented in a monastery by a monk.

English muffins

Despite the name, English muffins actually came to be in America. As the Kitchn recounts, Samuel Bath Thomas created the English muffin in New York City in 1880. Evidently, Thomas was inspired by a food item that's common in England, his home country: crumpets. His company, still bearing his last name, continues to be the biggest name in the English muffin game to this day.

An English muffin is a squat, textured, round baked good. It traditionally gets split in half and toasted, where the copious crevices — fondly referred to as "nooks and crannies" — get particularly well cooked and can soak up lots of slathered-on butter. Per most English muffin recipes, the base of these individual treats is typically coated in crunchy cornmeal. This adds additional texture and helps keep the muffins from sticking in the oven.

Having been around so long, it was inevitable that English muffins would embed themselves into our culture. One particularly notable — and ubiquitous — use of them is in the brunch classic Eggs Benedict. In the dish, a toasted, split muffin is topped with Canadian bacon, poached eggs, and a decadent slathering of Hollandaise sauce.

Babka

Babka is a rich, dramatic-looking bread that gets swirled with layers of filling — cinnamon sugar and chocolate are the two most famous. According to Food 52, it has its origins in Europe, where Jewish people would take leftover challah dough and roll it up with jam or spices and bake the loaf as a new confection. Immigrants brought this tradition to the U.S., where it enjoyed regional success — particularly in New York City — but general notoriety can be traced back to the popular 1990s sitcom Seinfeld. In one memorable episode the characters spend an entire episode talking and fretting about acquiring a babka to bring to a friend's party. Many professionals today credit that episode with raising this sweet bread's profile and making more people aware of it.

Although it started out as a pareve treat — meaning it contained no dairy and was therefore suitable for certain Jewish religious requirements – these days most babka recipes are enriched with copious amounts of butter that lends a soft, cakelike texture and makes for an absolutely delicious end result.

The swirls of cinnamon or chocolate have also featured in many influencers' feeds since the striking look of this bread is almost as appealing as taking a bite of it. Babka happens to be having a moment right now and has become the signature dish of bakeries trying to make a reputation for themselves.

Tortilla

Spanish for "little cake," tortillas are a staple of Mexican food — and have been for millennia. As recounted in Texas Monthly, they were originally made with corn treated with limestone or wood ash through a process called nixtamalization, a treatment that helps remove the rough hull of the corn kernel and unlocks valuable vitamins and nutrients within.

Flour tortillas can get a bad rap and are sometimes thought of as an inauthentic interpretation of the "real" corn tortilla. Although the corn version is much older, the flour tortilla also originated in Mexico and has plenty of devotees in its native land — mostly across the north of the country. There are multiple theories regarding the pivot to flour. As journalist Gustavo Arellano told The Splendid Table, "[D]epending on the decade, sometimes people say it's a Jewish influence. Sometimes people say it's a Moorish influence. The reality is no one really knows how flour tortillas got started in Mexico except that it was done, again, up in Northern Mexico."

Tortillas can be featured in a huge variety of dishes and serve as a blank canvas for the vibrant and soulful food of Mexico. They get stuffed, rolled, fried, baked, layered, and so on with every conceivable combination of traditional ingredients. And we're all better off for it.

Cornbread

Cornbread, despite the name, is not strictly a bread; it is not leavened with yeast. However, its importance, particularly in the American South, as a food staple cannot be overstated. It is the automatic escort to any number of Southern dishes and is ready to soak up juices with aplomb.

There is also a huge regional division here. In the South, cornbread is typically savory and deeply browned, with very little — if any — sugar. In the North it usually is much more cakelike and soft. This is, in part, thanks to differences of available material, but it is also a reflection of how this baked good is used in each section of the country. In the South it's much more likely to be served as a component of a decidedly savory dinner. As Feast Magazine notes, in the North, it's more common to encounter it as a snack or even as a muffin.

Cornbread, thanks to not needing to fuss around with yeast, is also very easy to make. It comes together quickly and its distinctly corn-forward flavor is welcome on a table groaning with Southern specialties. Many cooks like to cook their cornbread in a cast iron skillet, the heavy metal retains heat very well and allows for the formation of a serious — and seriously browned — crust. This translates to a more savory, tastier finished product. The true pros coat the skillet with bacon fat first, for an extra hit of smoky, porky goodness.

Breadsticks

Although the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the word breadsticks may be a soft, seasoned tube that is included in Olive Garden's soup, salad, and breadsticks combo meal, the real deal is decidedly different. In Italy, a breadstick takes the form of grissini. These thin, brittle treats are used as an hor d'oeuvre and get served alongside other antipasti specialties like salami, roasted peppers, prosciutto, and cheeses. They are sometimes coated with seasonings — sesame seeds are particularly popular — or have savory bits like olives or bits of cheese baked into them.

According to the Turin Italy Guide, grissini are native to the city of Turin in the northwestern region of Piedmont. There — and elsewhere — they are likely to be served with a glass of wine at the beginning of a meal. The dough is very straightforward and many recipes advocate using store bought pizza dough to fashion them. They can be twisted into a variety of shapes and sizes, depending on the use to which they are being put.

Breadsticks, as the Olive Garden figured out, are a great accompaniment to a hot soup. Providing some heft and substance, as well as a perfect dipping food, they can round out a simple meal.

Lavash

Lavash is a flatbread of Armenian origin. It holds tremendous cultural importance for the people of its native land. They not only depend on it for sustenance, but also cherish the seasonal rhythms of harvesting the wheat, milling the flour, and periodically preparing this soft bread. The process is complicated enough to warrant the assistance of at least one other bakers, and as Smithsonian Magazine notes, crafting this bread becomes a community building activity.

Armenia is a very old country, with traces of civilization stretching back many thousands of years. Armenia Travel details the evidence of human settlements from 90,000 BC here. This astonishing fact means that the people here have been practicing their crafts for a VERY long time. It's not surprising that they've gotten so good at it. Lavash is such a significant part of Armenian cultural patrimony that UNESCO declared it an item of intangible cultural significance.

The bread itself is a very simple, straightforward recipe. Typically made of just flour, salt, water, and yeast, some traditional practitioners use a leftover dough piece as a sort of rudimentary sourdough starter. This adds complexity to an otherwise very elementary bread. Lavash serves as a backdrop for all sorts of Armenian savory dishes and can be a blank canvas for whatever you may need to scoop up into its historic embrace.

Croissants

The French word for crescent, croissants have their origin in the Austrian capital of Vienna. According to Smithsonian Magazine, in 1683 the town withstood a siege by the Turkish armies which had been swallowing up European countries one by one. This triumph led to Viennese bakers to claim that their crescent shaped baked good, called a kipferl, was in fact a reference to the crescent moon on their erstwhile enemy's flag. When this was brought to Paris, the local bakers, too proud to bow to the superiority of another city's confectioners, decided to perfect the form and it has practically become a symbol of France.

Croissants are very complicated to make. In fact, the Guardian suggests leaving this one to the professionals since "life is too short." The process involves a yeasted base dough that enfolds a block of cold butter and then the whole thing is rolled out and folded on itself — like a letter — multiple times so that hundreds of layers of dough are separated by thin layers of butter. In the oven the butter melts and the steam puffs up and forms flaky layers. As Food & Wine explains, this technique is called lamination.

Other doughs — such as puff pastry — are also laminated but with croissants, the added complication of the yeast means that the entire process is not only fussier, but takes longer too. However, the end results are hard to argue with. A croissant ends up with an ultra flaky exterior surrounding a buttery, light and soft inside. The combination is addictive.

Sprouted

Although we refer to things such as wheat kernels as grains, they are in fact seeds. These tiny seeds, if given the right conditions, will start to sprout or germinate. This process makes for an incredibly nutritious and healthful end result. In preparation for feeding the growing plant, enzymes partially convert the starch inside the grain into vitamins, amino acids, and sugars.

According to the Los Angeles Times, because this can only happen to whole grains, sprouted breads enjoy many of the same health and nutrition benefits that whole wheat bread does. However, because many sprouted grain products include more than just wheat in their composition — often including things such as soybeans, lentils, barley, and/or spelt — they also end up having a more nutritious profile.

Sprouting also is supposed to improve the digestibility of the bread and it has anti-inflammatory properties which those with autoimmune diseases can appreciate, according to Web MD. However, there is a certain amount of debate as to whether sprouted bread is any better than un-sprouted whole grain bread or if it's all the same. Sprouted bread is also more expensive than the alternative and most manufacturers recommend that it be refrigerated since all of the parts of a grain or a seed that are prone to spoilage are still included in the finished product.

Quick breads

This category is broad, diverse, and not technically bread. Things like banana bread, zucchini bread, and muffins fall into this category. Many are loaf-shaped and have a similar light, fluffy texture to true bread. However, typically these baked goods rely not on yeast for lift, but on the sure bet of baking powder or baking soda. The possibilities of this open-ended formula are endless and if you can eat it, you can probably make it into a quick bread.

When making bread, gluten-development is of paramount importance since it is the gluten that gives the bread the structure needed to trap the gas released by fermenting yeast and become light and fluffy, as noted by Modernist Cuisine. In quick breads, you typically want as little gluten development as possible since there is no yeast involved and too much mixing can lead to a tough and dense finished product.

When deciding between baking powder and baking soda for these types of baked goods, the main thing to remember is that baking powder is self activating and needs only moisture and the heat of the oven to add air to things. Baking soda, however, needs some kind of acidic ingredient in the mix to react with and provide that puffing action. Things like buttermilk, sour cream, or even brown sugar can all provide that acidic environment necessary for this reaction.