The Untold Truth Of American Chinese Food

When you're looking for comforting food that gives you plenty of flavor at a low cost, American Chinese cuisine is hard to beat. Who can say no to the pleasures of well-made General Tso's chicken, beef with broccoli, or egg rolls? In fact, Uber Eats told Travel + Leisure that Chinese food was the third-most-popular cuisine on its platform in 2021.

And yet, despite its immense popularity, American Chinese cuisine isn't the most well-respected culinary tradition. Now that American diners can eat traditional regional Chinese cuisine, the old standbys from takeout restaurants are sometimes vilified as being fake or inauthentic. However, thinking about American Chinese food in this way unfairly demonizes a rich culinary tradition with roots that extend back well over a century. The story of American Chinese food is a tale of hard-working immigrants overcoming prejudices and hardships to create something beautiful in their adopted country. It might be more American than Chinese, but only a fool would say that American Chinese food doesn't taste good.

The gold rush brought the first large group of Chinese immigrants to America

While some Chinese immigrants arrived in Manhattan as early as 1800, the first period of large-scale Chinese migration to the U.S. began during the 1849 California Gold Rush. According to the Library of Congress, within two years of the news of gold in California making its way to Hong Kong, 25,000 Chinese immigrants had moved to the state. Some Chinese people even referred to America as Gold Mountain because of its reputation for riches.

However, for most of the new arrivals, gold mining didn't prove to be a reliable source of income, and many went on to work for U.S. railroad companies (via Library of Congress). Others became entrepreneurs, opening stores, washing clothes, and running restaurants.

Per the CalAsian Chamber of Commerce, two Chinese restaurants opened in San Francisco in 1849. The first (and perhaps America's first Chinese restaurant), Canton Restaurant, was a grand 300-seat dining room that served as a hub for Chinese miners. The second, Macao and Woosung Restaurant, was owned by Norman Asing, a notable political activist who advocated for the civil rights of Chinese immigrants.

San Francisco's Chinatown grew after the completion of the railroad

According to PBS, by 1853 an area of central San Francisco near Portsmouth Square was already being referred to by newspapers as Chinatown. In 1868 and 1869, two events occurred that made San Francisco's Chinatown grow rapidly: First, the Burlingame-Seward Treaty granted Chinese citizens the right to immigrate to America in unlimited numbers. Second, the railroad was completed, which meant thousands of Chinese laborers needed to find new ways to make a living. Many of them chose to start businesses in San Francisco. Chinese laundries in the city expanded in number from 2,000 in 1870 to 7,500 in 1880.

During this same time period, more Chinese restaurants began to open. By 1882, there were nearly 30 Chinese restaurants in San Francisco, up from around eight in 1849 (via Comparative American Studies at Oberlin). However, restaurants didn't see the same success as other Chinese enterprises. This was partly due to the intense backlash against Chinese immigrants from white San Franciscans. Non-Chinese city residents did not want to eat at Chinese restaurants, and restaurant dining wasn't particularly popular among the Chinese population.

New York City's Chinatown welcomed transplants from the West Coast

Unfortunately, the anti-Chinese backlash in San Francisco manifested in acts of violence. In 1877 mobs of nativist rioters burned down Chinese-owned businesses and looted many Chinatown storefronts (via SFGate). According to Eater, the unrest in San Francisco convinced many Chinese immigrants who had settled on the West Coast to move to New York. By 1880, New York City had its own bustling Chinatown filled with restaurants and other businesses.

The first Chinese restaurants in New York were aimed solely at Chinese clientele, but by the turn of the 20th century, non-Chinese New Yorkers began eating in Chinatown as well. One example of a restaurant that served both Chinese and non-Chinese diners was Port Arthur, a massive two-story space filled with imported furniture and decorations.

When New York Chinatown became a popular destination for residents from other parts of the city, Chinese cooks began making recipes that catered to the palates of these new visitors. This is when chefs started inventing new American Chinese dishes, cooking a style of food that was different from what was eaten in China.

Racist US immigration laws encouraged Chinese immigrants to open restaurants

The growth of the Chinese restaurant scene in the early 20th century was spurred on by an unlikely force: racist laws. Per the Library of Congress, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barred all immigration of Chinese laborers and made it impossible for Chinese immigrants to become U.S. citizens. However, there was a loophole in the law: If a Chinese person owned one of a few specific types of business, they could qualify for a merchant visa (via NPR). That meant they could travel freely between China and the U.S., bringing Chinese employees (often family members) to America.

Restaurants didn't originally qualify for this exemption, but in 1915 they were added to the list of merchant visa businesses. After this change in the law, the number of Chinese restaurants in the U.S. skyrocketed. By 1930, there were four times as many Chinese restaurants as there had been in 1910. The merchant visa exemption allowed American Chinese people, a majority of whom were single men, to reconnect with their families in China.

We have the 1906 San Francisco earthquake to thank for Chinatown architecture

If you live in a city with a Chinatown, it probably has a very specific look: Western-style buildings with facades that incorporate elements of traditional Chinese architecture such as pagodas (via Arch Daily). While it might seem like this style of architecture emerged organically as a way to remind Chinese immigrants of home, it was actually designed to protect one specific Chinatown from persecution.

The San Francisco earthquake of 1906 destroyed much of the city, including all of Chinatown. The city's government viewed the destruction as an opportunity to move Chinatown away from the center of town, as it was deemed to be an eyesore and a high-crime area, according to the Nob Hill Gazette. However, the government's efforts to move Chinatown were thwarted by an American-born Chinese businessman named Look Tin Eli, who raised money to rebuild the neighborhood on the site where it had always stood (via PBS).

During the rebuilding process, Chinatown's businessmen hired architects to construct buildings that evoked Chinese aesthetics. As the Nob Hill Gazette notes, this was a self-conscious effort to recast the neighborhood as a kind of theme park for tourists and to clean up its image. The effort was successful and turned San Francisco's Chinatown into a must-see destination for travelers. Per Arch Daily, this new style of Chinatown architecture soon spread to other cities.

The first Chinese food in America was Cantonese

American Chinese food is its own distinctive cuisine, but it has its roots in one specific style of Chinese regional cooking: Cantonese (via Serious Eats). Cantonese food comes from the province of Guangdong, specifically the area close to the Pearl River Delta. This is the region where most of the earliest Chinese immigrants to the U.S. came from. Since Chinese immigration was heavily restricted for decades, the specialties from the Pearl River Delta were the primary influence on American Chinese food for many years, according to Digest.

Serious Eats says that the main goal of traditional Cantonese chefs is to make food taste like the best version of itself, rather than transforming its flavor. It uses fewer spices and hot chile peppers than some other styles of Chinese cuisine and instead opts for ingredients like scallions, ginger, garlic, and soy sauce to add flavor. Cantonese food isn't just popular in America; you can find Cantonese restaurants throughout China and in many other countries.

Chinese-American cooks had to adapt to their new home in America

One of the reasons American Chinese cuisine ended up being so different from the Cantonese food you find in China is that cooks in America had to work with the ingredients that were available to them (via CNN). This often involved replacing Asian ingredients like bean sprouts with ones that were easier to find in the U.S. like cabbage, according to Eater.

American Chinese food also took on a distinctive character because many of the people who made it weren't cooks before they traveled to the U.S. A large percentage of the first Chinese immigrants were male laborers who would not have learned how to cook in China (via Comparative American Studies at Oberlin). For this reason, they prioritized simple easy dishes like chop suey, a stir-fry of assorted meat and vegetables.

The dishes served by Chinese cooks in America changed even more once they started serving food to a white American audience. Chop suey, for instance, originally contained cuts of offal like tripe, chicken gizzards, and liver. As time passed, it became more common to make the dish with cuts of meat that were more familiar to American tastes.

Tiki bars and American Chinese restaurants influenced each other

Tiki bars and American Chinese restaurants have a long history of cross-pollination. Tiki culture, which was a huge fad during the mid-20th century, was based on selling white American consumers a fictional fantasy version of Polynesian traditions (via Punch). Don the Beachcomber and Trader Vic's, two restaurants that set the template for tiki bars everywhere, served Americanized versions of Cantonese food with a tropical twist.

Although the first wave of tiki bars was started by white men, LAist points out that Chinese-American restaurateurs also took advantage of the fad and started opening their own tiki places. Chinese-American-owned restaurants like Madame Wu's Garden and Bali Hai started serving up Americanized Cantonese food in a tiki setting.

Punch notes that some American Chinese restaurants also started adding tiki drinks to their menus, even if they didn't go all-out with the tropical decor. The influence of tiki restaurants lives on in the menus of American Chinese restaurants to this day. Per Atlas Obscura, staples like crab rangoon and the pu pu platter were both originally served at tiki bars

Chinese buffets popped up after World War II

Although one of America's first Chinese restaurants, the Macao and Woosung Restaurant, was an all-you-can-eat buffet, this style of American Chinese dining didn't become widespread until well into the 20th century. Interestingly, the first Chinese buffets that popped up in the 1940s were not in restaurants. Instead, they were special events held by clubs and church groups (via Sampan).

The first newspaper reference to a modern Chinese buffet restaurant in America is from 1949. The restaurant in question, Chang's, served up a choice of 20 entrees along with rice and soup to hungry Los Angelenos. In time, the offerings at Chinese buffets would grow to include a bewildering mishmash of American Chinese food, pizza, desserts, and even sushi (via Hyphen).

According to Bon Appétit, all-you-can-eat Chinese buffets peaked in popularity in the '90s. The boom in buffets was propelled by recent Fujianese immigrants, who appreciated low labor costs at buffets and the fact that most employees didn't have to speak English to successfully run a buffet. In more recent times, buffet-style dining is starting to disappear, and Chinese buffets are not immune to the downward trend.

Cecilia Chiang gave many American diners their first taste of real Chinese dishes

For the first half of the 20th century, the menus at most American Chinese restaurants were dominated by dishes like chop suey, chow mein, and egg foo young. These were either American inventions or at least very different from the versions of the dishes that would be served in China (via Eater). That began to change in the 1960s, and no one deserves more credit for this shift than Cecilia Chiang, who ran a famous restaurant called The Mandarin in San Francisco.

According to the Berkeley Library, Chiang specifically rejected the dishes that most Americans thought of as Chinese, saying "no chop suey in my menu and no egg fu yung. All this Chinatown stuff is a no-no." Instead, Hoodline notes that the Mandarin served dishes from China's Sichuan and Hunan regions, such as potstickers, tea-smoked duck, and kung pao chicken. The Mandarin built a devoted following, including celebrities like the band Jefferson Airplane.

Ironically, Chiang's son Peter later founded P.F. Chang's, the chain famous for serving a deep-fried, sugary, and thoroughly American version of Chinese food.

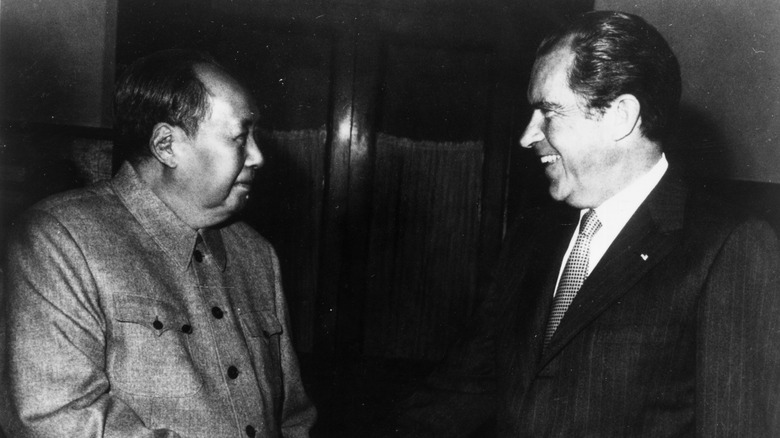

Richard Nixon helped popularize Chinese food in America

Traditional Chinese cuisine received yet another boost in popularity stateside from an unexpected champion: Richard Nixon (via Atlas Obscura). After the Chinese Communist Party took over the country's government, China and America antagonized each other for many years. In a historic move, Nixon visited China in 1972 in an effort to normalize relations between the two countries. The visit was important not just from a geopolitical standpoint, but also for culinary reasons.

Nixon and the Chinese Premier Zhou En Lai hosted lavish state dinners for each other during the U.S. president's visit. Media coverage of the food they ate made American diners curious to try unfamiliar dishes such as shark fin soup, coconut chicken, and Peking duck. After the visit, thousands of new Chinese restaurants opened across the country. The boom was so large and sudden that it became difficult for restaurateurs to find enough chefs to staff their new businesses, according to The New York Times.

Regional Chinese food became more popular after 1965

The sudden surge in the availability of traditional regional Chinese cuisine in America in the '60s and '70s can't all be chalked up to Cecilia Chiang and Richard Nixon. The passage of the Hart-Celler Act of 1965 was a more significant factor overall (via Comparative American Studies at Oberlin). This law significantly loosened the restrictions on Chinese immigration. Suddenly, immigrants from places like Hong Kong, Taiwan, and China's Sichuan province began arriving in America, bringing with them styles of Chinese food that had previously been difficult to find in this country.

According to The New York Times, the influx of new immigrants coincided with a sudden trend for Sichuan food in New York. Hunanese and Shanghainese food also became more popular during this time, per CAS Oberlin. Since restaurants in America's Chinatowns now had a customer base that included many recent Chinese immigrants, they no longer had to exclusively serve Americanized Cantonese fare. Chinese immigrants also began establishing enclaves in the suburbs, opening traditional Chinese restaurants far away from the old inner-city Chinatowns.

American Jews have a special relationship with Chinese food

According to Vox, many Jewish people in America eat Chinese food on Christmas day. It's a tradition that spans over 100 years, which Rabbi Joshua Eli Plaut notes began in Manhattan's Lower East Side at the turn of the 20th century (via Vox). During this time period, the neighborhood had large populations of both Jewish and Chinese immigrants. While most of America celebrated Christmas, Jewish people needed something else to do on that day. And, as journalist Jennifer 8. Lee told Forward, "The Jews and Chinese were the two largest non-Christian immigrant communities in America, noting that "They didn't keep a Christian calendar so their restaurants were open on Christmas."

Additionally, Rabbi Plaut argues that Chinese food was more in line with Kosher dietary restrictions than many other types of cuisine. Since there's almost no dairy in Chinese food, Jewish diners didn't have to worry about violating the rule against mixing dairy and meat. Also, in the earlier parts of the 20th century, Chinese restaurants were often a more welcoming environment for Jewish patrons than those owned by Christian Americans.

American Chinese food is an authentic food tradition

Although the food served at most American Chinese restaurants may not be very similar to what you'd find in China, that doesn't mean it's inauthentic or inferior. Rather, as Clarissa Wei argues at CNN, American Chinese food is an authentic American-born style of cuisine. As she points out, the roots of this style of food go all the way back to the late 1840s when Chinese immigrants in California were trying to cook food for each other. The dishes and cooking styles of American Chinese food have been practiced by cooks of Chinese descent in America for over a century and a half at this point.

Chef Julie Lau told CNN, "American-Chinese food is Chinese food," further explaining, "We take different flavors from Chinese cuisine, combine them and create an original flavor." Many American Chinese dishes that have been derided as inauthentic are actually adaptations of traditional foods. For example, an article in Digest argues that chop suey is from the Pearl River Delta region of Guandong, while General Tso's chicken was originally cooked in Taiwan.

The pandemic took a toll on American Chinese restaurants

The first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic wasn't easy for any restaurant, but it hit American Chinese restaurants particularly hard. According to CNN, data from credit and debit card transactions showed that over 50% of Chinese restaurants in the U.S. had shut down either temporarily or permanently by April of 2020.

In December of that year, Chinese restaurants were still struggling. Part of the problem was that the virus that causes COVID-19 was thought to have originated in a wet market in Wuhan, China. This led to racist assumptions from certain U.S. customers that Chinese restaurants in America were in some way unsafe or dirty (via PBS). These stereotypes go all the way back to the dawn of American Chinese cuisine in the 1850s when nativist white Americans felt threatened by Chinese immigrants.

The difficulties didn't end with slower business either. Chinese-American restaurant owners received prank calls and some businesses were vandalized. Even more seriously, racially-motivated violence against Asian Americans increased between 2019 and 2020, per an FBI report.