Chinese Restaurant Secrets You Can Use At Home

If you love, and we mean love Chinese food, you know that just settling for dining out isn't really an option. Even though your favorite takeout joint might be budget-friendly, it can still start to add up after the fourth or fifth visit in a month, and who among us can really go a week without Chinese food? This means that the only real option is to learn to cook it ourselves. But with such a rich, storied, and historic fare, where does one even begin? Well, why not start with our own backyard?

Chinese restaurants have much to teach us about the growth, evolution, and endless adaptability of one of the greatest cuisines in the world. With a little study, building a small pantry for Chinese food in your own kitchen isn't as daunting as it may seem. Believe it or not, some of these Chinese restaurant cooking techniques might just be game-changers for your kitchen skills.

1. The secret to making perfect rice every time? Leave it alone

Rice is incredibly easy to make if you know what you are doing, and avoid common mistakes when cooking rice. Cook it too long and it becomes sticky, use too little water and it's crunchy. If you really want that perfect, restaurant-style rice, it's always best to use a rice cooker. But don't worry, you can still achieve that same fluffy, unctuous rice on your stovetop, you just have to follow a few simple rules.

For starters, always rinse your rice. A few rinses in a colander until the water runs clear rids the rice of that excess starch. Ratios may vary, so check the packaging of your rice for proper instruction, but for the most part, 1 cup of water to 1 cup of rice works for most long-grain rice, although with Jasmine, adjust that to 1 ½ cups water to 1 cup rice. Use 1 1/4 : 1 for short grain.

To cook, simply add rice to your pot, top with water, a pinch of salt, cover, and bring to a boil. But here's the most important part: once the covered pot reaches a rolling boil, don't touch it at all! Leave it covered and reduce the heat to low, allowing it to steam for 18 minutes. Remove it from the heat, place a towel over the pot, and cover again, allowing it to rest for 15 more minutes before fluffing with a fork.

2. Always use day-old rice when making fried rice

There are dozens of different techniques, methods, and recipes for fried rice, but perhaps one thing that the best of the best tend to agree upon is using day-old rice. While freshly cooked rice can work in a pinch (although we highly recommend throwing it in the freezer for 20 minutes if you plan to cook with fresh rice), it's the tired starches of leftover rice that make them ideal for frying. While fresh rice tends to be sticky and starchy, leftover rice breaks apart nicely, preventing clumping, and leaving you with a freshly seasoned bite every time.

For perfect egg-fried rice, start by frying your egg in a little cooking oil, removing and setting aside. Next, fry your meat and veggies, and set aside. Then add your leftover rice in a couple tablespoons of oil, some chopped green onion, return your stir-fried ingredients to the pan, and season with a little soy sauce drizzled in from the sides of the pan so that it toasts. Toss until everything is nicely mingled and serve.

3. Give any meat that Chinese takeout tenderness by velveting it with corn starch

Ever bite into a stir fry and wonder how your favorite take out place makes their steak, pork, or chicken so incredibly fluffy and tender? The texture is a crucial part of Chinese cooking and a lot of those textures are achieved through the magic of cornstarch (via Bon Appétit).

Marinating your protein in a cornstarch slurry creates a protective coating that browns the meat and acts as a tenderizer, locking in juices and creating a texture to which the sauce more easily clings. Just mix equal parts cornstarch, soy sauce, and veggie oil, pour over the meat and mix thoroughly, covering and allowing it to marinate for at least 30 minutes. Feel free to experiment with the marinades, too! White pepper, oyster sauce, and Shaoxing wine make great variations. Then toss the marinated meats in piping hot frying oil in your wok or frying pan, brown, and set aside until you are ready to cook the rest of your dish, finishing the meats with the rest of the ingredients.

When adding the finished meat to soups or brothy sauces, the cornstarch has the additional function of thickening your sauces or broths to make velvety soups and thick, clingy sauces.

4. Give any pasta the springy bite of ramen noodles with baking soda

Suppose you've chopped your veggies and marinated your chicken, and you reach into the cabinet to pull out a package of ramen to complete your stir fry prep, only to discover that there's only a box of spaghetti in the pantry! Rather than running down to the bodega to buy some cheap, inferior ramen, consider ramenizing that spaghetti (or any pasta).

Ramen is typically made with alkaline-based minerals called kansui, but since kansui can be hard to find in the U.S., many chefs turn to baking soda since it is also a form of alkaline. While most chefs would blend the alkaline in with the flour when making the noodles, for our purposes it is perfectly effective to add it to our boiling water when cooking our pasta. Fair warning: baking soda can often impart a soapy, bitter taste, so use sparingly.

Daniel Gritzer of Serious Eats recommends using 2 teaspoons per quart of water, but if you are serving a super flavorful or rich broth, you could get away with using a full teaspoon per quart for a more toothy bite. To ramenize, add your baking soda to a pot of water or stock and bring to a boil, stirring frequently to calm down the foam, as the water will furiously bubble because of the baking soda. Cook your noodles according to the directions until al dente, and serve or add to your favorite recipe.

5. Keep these ingredients in the pantry to make just about any classic Chinese dish

Getting the hang of a cuisine as expansive as Chinese food can be daunting for anyone, particularly when trying to familiarize yourself with the aisles of your local Asian market. Fortunately for us, there are a few ingredients that seem to be staples in the Chinese culinary pantry that shouldn't break the bank for you to keep in stock.

Chef Ming Tsai suggested to Mashed to always keep a bottle of good soy sauce (tamari, if you're gluten-free), oyster sauce (vegetarian oyster sauce, if you don't do fish), sesame oil, rice vinegar, hoisin sauce, dried chilis, and citron peppercorns. We'd add to that list with a bottle of Shaoxing wine, a kind of cooking sherry that works well with dishes such as Mongolian beef and wonton soup.

We've found that by combining equal parts soy sauce and oyster sauce, you have built a good simmering sauce for a stir fry, but you've also created a great base for any number of combinations from the rest of the pantry. Try vinegar or Shaoxing wine to add a souring element, add some sugar to sweeten it up, or chilis for spice. With these eight ingredients, the possibilities are endless, and you should be able to make most recipes you come across at your favorite Chinese joint.

6. Don't cook with sesame oil, garnish with it

While it is a key staple in the Chinese recipe pantry, The Woks of Life stresses that it's important to know when and how to use sesame oil. While there are several options on the shelves of Asian markets, the most commonly called for, and the one likely hanging around on the shelf of your local grocery store is toasted sesame oil. Toasted sesame oil is an expensive ingredient, and is intended to be a luxurious seasoning rather than cooking oil. Ever get that burnt flavor in a stir fry that seems to coat everything? That's likely from trying to cook with and burning sesame oil.

We like using it as a finishing oil for egg drop or sweet and sour soup. Try a drizzle on finished stir fry, fried rice, or noodle dish. It also makes for a killer flavoring agent in marinades for meats and veggies.

It's important to pay attention to the varying darkness of the toasted sesame oils on your grocer's shelf. The darker the oil, the more pungent the flavor, and the more sparingly it should be used. That's why you should always measure your sesame oil if cooking with a recipe, or drizzle gently if you're winging it.

7. Use cornstarch to thicken broths, gravies, and sauces

One could argue that cornstarch is as important to Chinese cooking as making a roux is for French and Cajun cuisine, because it is used in just about everything. Cornstarch is used as a marinade, to tenderize or velvet meat and fish, it can be used for a quick dredge on meats and veggies before deep frying them to produce coarse, crispy textures, or it can be used when making noodles to round out the flavor and create chewier doughs. But perhaps the most common usage is that of a thickener in sauces and soups (via The Woks of Life).

Try making a cornstarch slurry of a couple of tablespoons of water to equal parts corn starch, and stir it until the starch dissolves. You'll have to stir it regularly until you use it, as it will clump up if not freshly stirred. When you are almost done cooking your stir fry, while there is still a fair amount of liquid in the bottom of the wok or pan, stir in a little of that cornstarch slurry and watch as the sauce marginally thickens and clings to your meat or veggies. You can also add it to your broth when making egg drop or hot and sour soup to create that classic velvety texture. Just be careful to stir it in slowly, constantly whisking the soup to prevent any clumping.

8. Knowing the uses of light and dark soy sauce is the key to perfect seasoning

Something that can take some time for the uninitiated Western cook to get used to in Chinese cooking is that, while in Western fare nearly all of the seasoning comes from salting your food as it cooks, Chinese cooks use a melange of sauces to season their dishes. Many dishes call for both light and dark soy sauces, some will also call for salt, some oyster sauce, or fish sauce. All of these sauces contain sodium, which, when not handled properly can leave your dish tasting too salty, particularly if you are also using an American boxed stock that is already seasoned. One of the easiest ways to mess up your meal is not knowing the difference between light and dark soy sauces.

What you typically find on Western grocery store shelves is light soy sauce — think of the ubiquitous Kikkoman bottle. When most recipes call for soy sauce, they are asking for the light version. Dark soy sauce has added caramel, making it thicker, sweeter, and as the name suggests, darker. It is primarily used as a coloring agent and is often called for in tandem with light soy sauce. You can easily tell the difference by holding the two bottles up to the light and tilting them. Dark soy sauce will leave a syrupy film that runs down the neck of the bottle while the light version will drip away relatively cleanly.

9. Par-freezing your meats makes them easier to slice thin

Many Chinese dishes, particularly stir fry dishes like lo mein, call for thinly sliced beef, and hot pots call for even thinner cuts of meat. This can be a problem, particularly if you do not live in a city with a good butcher who will cut your meat to order. One quick trick to easily cut through beef is to par-freeze it. Simply toss the wrapped package of meat in the freezer and allow it to chill out for a half-hour to an hour, depending on the thickness of the cut. Once partially frozen, the meat will be nice and firm, and a sharp knife should easily glide through it.

Knowing what kind of beef is just as important as knowing how to cut it for each dish. The Woks of Life suggests flank steak as a good option. It's quality, but economical, and doesn't require delicate handling. Cut flank steak along the grain to ensure the best texture when cooked. Chuck steak is a more affordable option that works just as well. Be sure to cut boneless chuck against the grain to yield tender cuts of meat when it hits the heat.

10. Turn cheap cuts of meat into succulent stews by red cooking them

There's no better way to handle tough cuts of meat than with a braise. The slow and low cooking technique breaks down tough muscles and turns them into tender eats. A famous Chinese braise method called hong shao, or red cooking, originated in Shanghai, but is now ubiquitous throughout China and American-Chinese menus. It is most famously done with pork belly, but can be made with just about any cut of pork or beef.

Chinese Cooking Demystified likes making theirs with bone-in pork ribs, and it's a great way to learn the process. Start by blanching the meat in water briefly, rinsing beneath the sink, and drying with a paper towel. Fry aromatics like green onion, garlic, ginger, five-spice, and Shaoxing wine, then add water, sugar, soy sauce, and spices like Sichuan peppercorns. Bring to a boil before covering and reducing to simmer on low for 45 minutes up to an hour, depending on what you are cooking. Then uncover, crank up the heat and allow the sauce to reduce by 2/3 before stirring in a cornstarch slurry, and seasoning to taste. Serve with white rice and garnish with sliced green onion to a table full of hungry guests.

11. Don't be afraid to crank up the heat

A key to Chinese cooking is wok hei, which literally translates as "wok energy," and refers to the vigorous tossing that chefs do over the incredibly high heat of their stoves. Most Chinese restaurants use insanely high octane burners that are basically tiny jet engines, pumping out well over 100,000 BTU. Compare that to a home burner which fires at a measly 400-18,000 BTU. A chef constantly has to move food around in the pan to keep it from burning, since the bottom of a wok can reach a whopping 750 degrees. This high heat creates a Maillard reaction, deeply browning the ingredients and bringing out rich, carbonized flavors.

To emulate this heat on your home burner, you'll likely want to run it around a medium-high setting, bringing an empty wok to a scorching hot temperature before adding in any oil with a really high smoke point (peanut oil works great in this context, with a smoke point of 410 degrees). J. Kenji Lopez-Alt has the extremely unique approach, of cooking over high heat while simultaneously blasting the top of the wok with a handheld blowtorch. For those less adventurous and who might not even have a wok, we think that even in your frying pan, you'd probably be fine cooking over medium-high heat, stirring/tossing frequently.

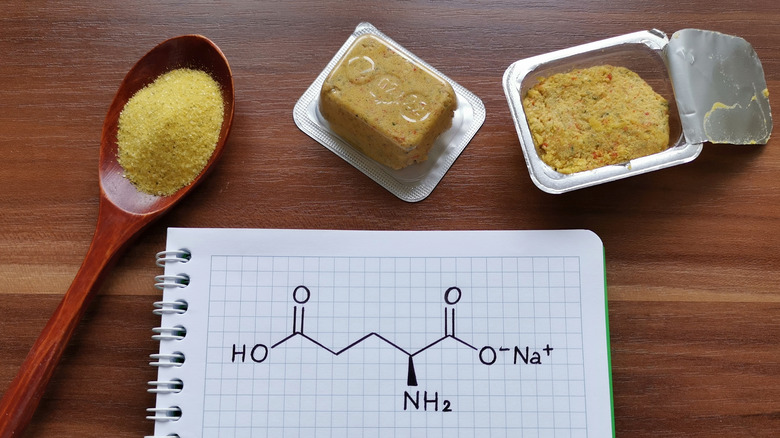

12. Don't be fooled, MSG is your friend

By now one would hope that we've all overcome the false and rather ignorant belief that Monosodium Glutamate, or MSG, causes headaches or is, in some way, bad for you. But never-the-less, just two years ago celebrity chefs like Eddie Huang had to take to the media to petition for Webster's Dictionary to pull the phrase "Chinese Restaurant Syndrome" from their dictionary. As Food Lab's J. Kenji Lopez-Alt regularly points out, MSG has widely been deemed safe and side-effect free in study after study, with the exception of an extremely small segment of the population, whom studies suggest should not eat MSG on an empty stomach.

The fact of the matter is that MSG is an amino acid that is regularly found in the kelp used to make staple ingredients like kombu. Isolating the amino acid and using it as a singular ingredient allows chefs to access a 5th flavor on our palate — umami. Perhaps the most incredible thing about MSG is just how widely it can be used. Try it in soups, stir fries, salad dressings, or marinades to give your dishes a powerfully savory punch and to create a depth of flavor in otherwise straightforward foods.