The Untold Truth Of Himalayan Salt

The history of humankind's interaction with salt is both long and illustrious. The mineral, which is primarily composed of sodium chloride, has been utilized throughout history in a variety of ways; as money, a medical antiseptic, and of course as a dietary supplement (per Time Magazine). Historically, areas fortunate enough to have rich, readily available salt reserves often relied upon its exportation for financial and social gain. Ancient salt roads that crisscross countries such as the Via Salaria attest to this fact and underline the importance of salt in every community.

In the 21st century, there is no longer any need for long treks to visit salt abundant areas, nor to haggle with a wily salt merchant upon arrival. Instead, the mineral has become widely available, leading to an overconsumption of salt occurring in many societies. The overabundance of salt is largely thanks to improved technology which allows humans to access previously inaccessible salt deposits, such as those deep underground. Perhaps the most famous of these rock salts is the pink-hued Himalayan variety, which has risen to prominence due to its purported health benefits, supposed superior flavor, and beautiful appearance. However, due to a ferociously competitive salt market, and ingenious marketing strategies, it can be hard to discern crystallized fact from flaky figment. In response to this dilemma, we have dug deep into Himalayan salt's rose-tinted history in order to discuss whether this culinary fad is actually worth its salt.

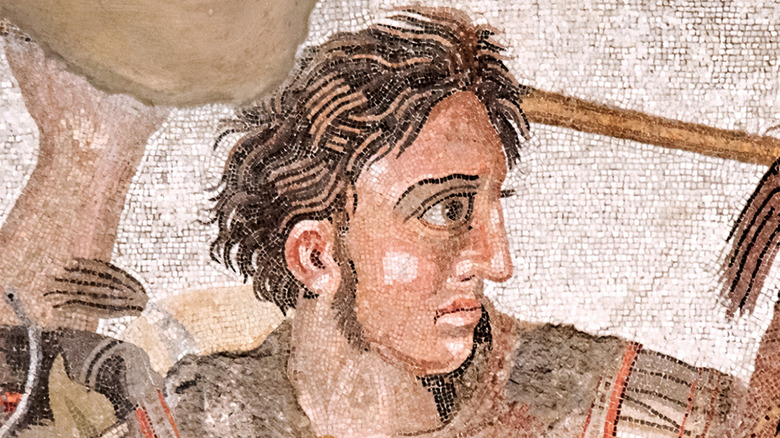

Himalayan salt was supposedly discovered by Alexander the Great

Alexander the Great, King of Macedonia from 336 BC till his death in 323 BC, and ruler of an empire that stretched from the shores of the Aegean Sea to India. During his lifetime and the millennia since, he has been remembered as one of the world's greatest military commanders, the founder of the city of Alexandria, and an astute political strategist.

Alexander's reputation was built upon brutal military campaigns which led him and his army deep into Asia. After one of his most ferocious battles against King Porus at the Jhelum River in modern-day Punjab, Pakistan in 326 BC, Alexander was to discover yet another wonder in this strange and foreign land. Or rather his horses were. They began to lick nearby rocks and Alexander's perplexed cavalrymen copied them and to their surprise found the rocks to be salty (per Ancient Origins).

Whilst Alexander and his army first discovered salt in the Punjab region of Pakistan over 2,000 years ago, extraction only began at what was to become the world's second largest salt mine in the 13th century when leaders of the Janjua-Raja tribe established commercial mining in the area. Due to the relative scarcity and thus valuable nature of salt, it is thought that small-scale salt gathering operations will have occurred in the Punjab region before the 13th century, although there is little in the way of definitive proof.

Himalayan salt is almost exclusively mined from the Salt Range in Punjab, Pakistan

The name Himalayan salt conjures in the mind an image of a mythical snow-capped peak, draped in mist, with hidden pink treasures residing deep in its bowels. Yet, the reality is that Himalayan salt is mined 186 miles away from the famed Himalayan mountain range (per Business Insider), in the appropriately named Salt Range, a series of much more diminutive mountains in the Punjab province of Pakistan.

Standing at a measly average height of 2,200 feet (per Britannica), the Salt Range definitely does not live up to the lofty imaginations associated with Himalayan topography. However, what it lacks in stature the Salt Range more than makes up for below the surface. Three main mines located in the Salt Range: Khewra, Kalabagh, and Warchha offer near inexhaustible reserves, with Khewra alone estimated at having deposits of 6.7 billion tons of Himalayan salt (per Salt Works). The area is also rich in other resources with middle-grade coal deposits, estimated at 213 million tonnes having been identified at Dandot, Pidh, and Makarwāl Kheji. Large limestone and dolomite deposits are also being mined in the area.

The Salt Range formed due to a myriad of geological processes

The collision between the Indian tectonic plate and the Eurasian plate began some 50 million years ago and has formed both the Himalaya and the Tibetan Plateau. By comparison, the Salt Range, which is born from the same geological collision, only began to form a few million years ago (per The Geological Society).

Just like the Himalayas themselves, the Salt Range was at one point the bottom of a shallow sea (per UNESCO) called Tethys Sea which evaporated during the collision of the two continental plates. It is thought that the drying out of this ocean some 600 million years ago, and subsequent crystallization of the salt within it, is what has led the Punjab region to be so rich in salt.

The diverse variety of minerals and rocks, when coupled with major geological processes that are clearly visible due to a lack of vegetation, has led to the area being labeled the "field museum of geology." Paleontologists and anthropologists also find the area of great interest with numerous fossils having been discovered in the area, including the remains of a prehistoric ape and tools used by humans in the Lower Palaeolithic period (per UNESCO).

The most prominent source of Himalayan salt is the Khewra Salt Mine

Clocking in at an impressive 110 sq km (per Atlas Obscura) the Khewra Salt Mine is the second largest salt mine in the world, and churns out approximately 325,000 tons of Himalayan salt per year. Located in the Salt Range, the mine accesses seven salt beds, which if combined, would be approximately 150 meters thick. However, not all this salt can be mined; about half must remain for structural integrity to prevent the mine from collapsing in what is known as the room and pillar technique.

The mine boasts a number of amenities including an electronic railway, mosque, and the world's only operational post office made from salt (per Atlas Obscura). Unsurprisingly, the beauty and status of such a place attracts huge swathes of tourists every year, upwards of nearly half a million. In an attempt to widen the appeal of the mines and to exemplify the products purported health benefits the Pakistan Mineral Development Corporation has built an asthma resort inside the mine, where up to 20 patients can benefit from inhaling the natural salt particles in the air (per Dawn). Plans are in place to expand the clinic so it can accommodate up to 100 patients at any time.

The Khewra Salt Mine has been ran by a number of governments

What is now modern-day Pakistan has seen the rule of a number of empires and governments in recent history. Unsurprisingly, each of these rulers exerted their influence over the highly profitable Himalayan salt reserves.

The Mughal Empire, which kickstarted commercial mining at the Khewra salt mine, traded the pink salt crystals in distant markets as far away as central Asia (per UNESCO). After the death of Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah I in 1712 AD, the dynasty sank into chaotic infighting and was soon swept aside by the various other factions (per Britannica). Chief among these was the Sikh Empire which ruled from its base in Punjab from 1799 until the early 1840s under the leadership of their talisman Ranjit Singh, and his son Duleep Singh until they too were forced to relinquish their hold on the mines.

The beneficiary this time was the British Empire, which wasted little time making sweeping changes to maximize the efficiency of Khewra Salt Mine. Under the guidance of an engineer by the name of Dr. H. Warth they widened passages, developed tunnels, and utilized the 50/50 room and pillar rule for salt extraction.

However, poor working conditions and mistreatment by the British Empire, which involved locking miners in Khewra Salt Mine until they had met their quotas led to a resistance movement and eventual strike. Soldiers were called to Khewra mine in response and 12 innocent miners were shot and killed.

Pakistan is trying to reclaim the Himalayan salt business from India

Pakistan has been in charge of all mining within the Punjab region, and thus practically all Himalayan salt production globally, since the nation gained independence in 1947. However, until recently, the majority of Himalayan salt sold to the global market has been processed and distributed in India, with no recognition of its Pakistani origin. Whilst an incorrectly applied "made in India" label may seem a small discrepancy to some, it belies a serious economic situation for Pakistani salt producers (per NPR).

Historically, Pakistan lacked the means to process the blocks of Himalayan salt and was thus forced to export it to India at $40/ton. Here the salt was handled and sold to global markets at $300/ton (via Business Insider). A worsening political relationship between the two nations culminated in 2019 when Pakistan banned bilateral trade with India, crippling the export-orientated salt business. Speaking to Business insider Waqas Panjwani, CEO of RM Salt was optimistic about the opportunities the ban would bring to Pakistani businesses stating "Twenty-three percent of Pakistan's rock salt was exported to India as raw material. Then it was re-exported overseas ... The government's decision will definitely benefit us".

The goal of returning the salt profits to Pakistan is a lofty one. Many suppliers lack the language skills or resources to deal directly with Western markets, leading some to suggest that few Pakistani businesses will actually benefit from the ban.

Himalayan salt contains more impurities than regular table salt

Himalayan salt is a rock salt which means it has already solidified before being harvested. On the other hand, white marine salt is produced by the evaporation of salty water. As previously reported by Mashed, the difference between how the two salts are harvested does normally produce slight discrepancies in look, texture, and taste. However, in the case of Himalayan salt, the differences are much more evident.

For those who have never seen it, Himalayan salt looks markedly different from its counterparts. Most notably, Himalayan salt often has a pink hue. This is not due to the addition of colorings or additives, but remarkably because of the impurities found naturally within the product itself (per Online Rock Salt). The trace minerals predominantly responsible for this color are calcium, potassium, and magnesium (per WebMD). With up to 84 trace minerals being found in Himalayan salt (per Livestrong), Himalayan salt has a lower overall percentage of Sodium Chloride than its marine alternatives. Indeed, it is the inclusion of these trace minerals, which are often not found in the aforementioned, purer marine salt, that has led some to argue that Himalayan salt is nutritionally superior to other salts (per Science-based Medicine).

Himalayan salt is actually less healthy than regular salt

Despite the prevalence of numerous trace minerals, ingesting Himalayan salt has been shown to not be nutritionally superior to other, purer salts. This is mainly because the concentration of these trace minerals is so small as to make no impact (per WebMD).

Misinformation concerning the purported health benefits of Himalayan salt is rife. However, governments and governing bodies have sought to crack down on misinformation as exemplified by the FDA lawsuit filed against "Herbs of Light," a business that made misleading claims as to the benefits of various products including Himalayan salt, by stating misinformation such as "Using salts would stop cholera and typhoid with decided and immediate success in every case."

Iodine is required by the thyroid gland to produce hormones. As Iodine cannot be produced by humans, we must ingest sufficient amounts in order to remain healthy. If our diet lacks sufficient iodine we can develop a deficiency that results in the enlargement of the thyroid gland and other serious complications. As Himalayan salt is not iodized like regular, commercial salt is, solely utilizing Himalayan salt can contribute to individuals developing an iodine deficiency and the negative health impacts associated with it. Furthermore, the normal risks associated with consuming salt are still applicable to Himalayan salt. As reported by The Harvard School of Public Health, high blood pressure, chronic kidney disease, and osteoporosis can all be caused, or worsened by diets high in salt.

Himalayan salt is more expensive than regular salt

As a gourmet product Himalayan salt is sold at a much higher price than its common counterparts. Indeed, Business Insider reported Himalayan salt as being up to 20 times more expensive. But with its purported health benefits being highly contested, the question must be asked why people are willing to pay so much?

It is thought that the salt's distinctive color gives it a definitive edge over regular salt. However, its beautiful appearance does a lot more than add color to a plate. It also provides physical "proof" of the mineral impurities that carry Himalayan salt's purported health benefits.

As reported by The Atlantic, the pink hue is a marketer's dream because without this visual cue it is expected that many would be slower to believe the sweeping health statements made about the product. Add to this the Eastern connotation associated with the product and you have an item ripe for fetishization by a growing health-conscious Western population. As stated by Ali Bouzari, a chef and food scientist "I don't know that pink salt is anyone's hallowed cultural touchstone. But I wonder if it was called Pakistani, if people would be quite as taken with it."

Himalayan salt owes a its popularity to a wellness trend

As a product, Himalayan salt has transcended from the culinary world into the wellness sphere with startling ease. What was once a condiment is now so much more with the raw product ending up in beauty products, home décor, and even spa facilities.

The latter has been adopted by a wide range of individuals with spas across the world touting the product's apparent ability to open airways and thus combat conditions such as asthma (per The New York Times). However, this trend for products that ride the line between food and wellness products has been around before Himalayan salt arrived on the scene. As stated by restaurant editor of Eater Hillary Dixler Canavan to The Atlantic "Gwyneth Paltrow once dipped a French fry in Goop face cream and ate it to show how organic it is ... There is this idea that your beauty supply should be food, and your food should be beauty, as a signifier that you really value natural and organic ideals."

However, wellness fads can be at best expensive and at worst harmful. One which potentially falls into the latter category is drinking so-called Sole Water; a blend of Himalayan salt and water. This fad which has gained traction in wellness circles is suggested as having many of the same contested benefits of ingesting the salt in its solid form. However, drinking sole water will increase a person's salt ingestion dramatically, a pertinent issue for Western individuals whose diets are already overloaded with salt.

Himalayan salt is used to make a variety of objects

As well as being used as a garnish, Himalayan salt, due to its structural integrity, has been turned into a variety of products mainly for the Western market. Kitchenware is a popular choice for craftsmen, with Himalayan salt often being carved into shot glasses and solid cooking blocks. These blocks can be heated directly (per The New York Times) and used as a surface to fry a variety of ingredients from eggs to steak, the idea being that sufficient salt is added during the process. As stated by supplier Salt Works "Foods placed on a Himalayan crystal salt slab take on a light, clean, naturally salty flavor while absorbing minerals necessary for good health and longevity."

However, the most popular items have nothing to do with the kitchen. Salt lamps and so-called zen blocks meet the demand for Himalayan salt wellness products by promising to purify the air, and emit negatively charged ions. However the efficacy of such products has been challenged, most namely because the lamps do not approach temperatures anywhere near the 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit required to dissociate ions.

Numerous celebrity chefs sell branded Himalayan salt

The gourmet salt market is soaring. As reported by British grocer Tesco, in 2019 demand for Himalayan salt increased by an astonishing 2,000%. Whether this was fueled by excess disposable income and booming interest in home cooking due to the Coronavirus pandemic remains to be seen. However, with gourmet salt now contributing to 40% of Tesco's overall salt sales it can be suggested that this is no longer some passing trend.

Well attuned to this fact is a whole host of celebrity chefs who are looking to profit off this sudden surge in gourmet salt sales. First and foremost amongst these is Nusret Gökçe, who is better known by his alias; Salt Bae. Despite the fact Salt Bae prefers to top his famous steaks with a flourish of Maldon salt (per Mashed), he still sells a Himalayan salt under the title SaltBae Himalayan Pink Salt. Another entrepreneurial chef who has jumped on the Himalayan salt bandwagon is British star Jaime Oliver whose own Himalayan Pink Salt is being sold in British mega-chain Sainsburys.

However, going one step further is American chef David Burke, who is an ardent user of Himalayan salt, having previously used a wall of Himalayan salt blocks to age his steaks. Burke can also boast of having brought Himalayan salt to the attention of America as he used the then uncommon ingredient in the 2004 season of "Iron Chef" for his dish Lamb Carpaccio with Pink Himalayan Salt.