The Untold Truth Of General Tso's Chicken

We all know the dish; sweet, tangy, sometimes a little spicy. And let's face it, there's nothing like a big serving of General Tso's chicken after a boozy night out with friends, or even just delivered straight to your door on a day when it's just a little too cold to venture out for dinner.

To most of us, it's just a standard dish that we see on nearly every Chinese take-out menu, but General Tso's chicken, like most of the dishes on that menu, has a much deeper story. It's a story about some of the first immigrants from the east to set foot on American soil. While being a small minority of the population, they would prove to be pioneering entrepreneurs, who helped build the American infrastructure and would eventually create one of the largest culinary traditions in America.

With over 40,000 Chinese restaurants around the U.S. and hundreds of dishes on each menu, it could get overwhelming to dig into the history of every single one. But that's part of what make's General Tso's so interesting. In a lot of ways this saccharine, sour dish lays out the history of Chinese-American cuisine in a single plate.

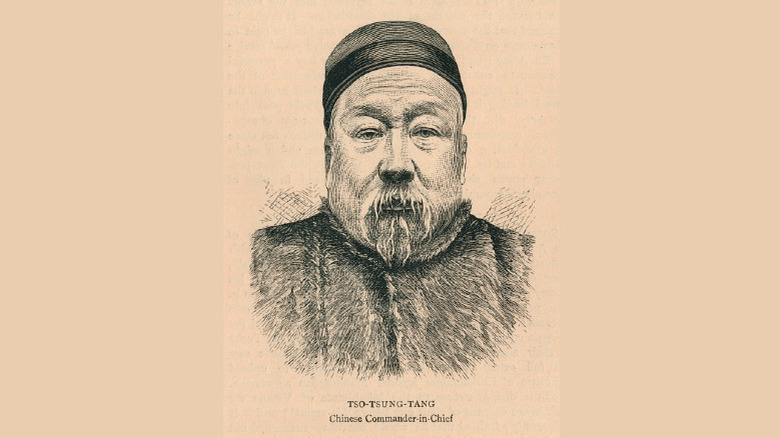

General Tso was a real person, and he was certainly no chicken

General Zuo Zongtang was actually a political administrator, nobleman, and military leader born in the early 1800s in Hunan, China. He fought to suppress the rebellions and uprisings that threatened to topple the Imperial government at the time with methods both tactically brutal, and in other cases, diplomatically brilliant. Whether it was overseeing the conquest of Central China or using taxation and the implementation of Western technology to quiet dissidents, his methods earned him respect both among the powerful and the people.

All-in-all, the real General Tso was a fierce traditionalist, fighting for the preservation of Chinese culture and heritage. So it is both ironic, and in some ways fitting, that most of the world would come to know his name through a dish that only loosely resembles the food from his region. After all, as NPR points out, most cuisine from Hunan shies away from the blending of sweet and savory flavors. One thing we do know for sure is that General Tso never ate the chicken of his namesake.

Ironically, the Chinese Exclusion Act created a Chinese restaurant boom

Perhaps the most influential force in the explosion of Chinese restaurants was the racist and xenophobic law intended to squash Chinese immigration, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (via NPR). The act effectively stopped any new immigrants from coming to the U.S., even denying re-entry to legal immigrants who had returned home for a visit, with a few key exceptions for Merchant Visas, which would allow certain businessmen to travel and even bring employees with them into the country. Restaurants just so happened to be on that list of approved merchants.

At the time of the law's passing, a large portion of the 300,000 Chinese immigrants living in America was based in San Francisco. Rather than compete with one another for the few businesses afforded to them within the law, a diaspora of immigrants spread across the country. The number of Chinese restaurants doubled between 1910 and 1920, and doubled again between 1920 and 1930. A restaurant surge that paved the way for the invention of all of our Chinese take-out cult classics.

The mass production of Chinese restaurant menus helped spread General Tso's chicken around the US

When that Chinese culture migration spread across the country, it didn't happen haphazardly. Long before the passage of the Exclusion Act, a number of regional Chinese associations had sprung up to help find work, healthcare, and other forms of aid for Chinese immigrants. According to the documentary "The Search For General Tso," after the Act's passage, these associations began assigning locations for immigrants to open their restaurants and even helped in printing menus and helping to standardize the kinds of cuisine on each menu.

Ever wonder why most Chinese restaurant take-out menus look strikingly similar, no matter where in the country you travel? Because most Chinese takeout food is deliberated, corroborated, consolidated, and promoted by these regional associations. In New York, for example, there is a two-block section of print shops that is responsible for printing thousands of Chinese restaurant menus around the country (via The New York Times). This intentional standardization of Chinese food in America helped to make regional trends like General Tso's Chicken nationally popular.

Richard Nixon accidentally spawned a Chinese food trend in America overnight

When Richard Nixon visited China in 1972, it was the first time a President had visited China since the communist revolution in 1949. Anti-Chinese sentiment had been high since the Korean War, leaving Chinese restaurants in the lurch. But with news reports revolving around a series of State dinners, Americans watched as the President indulged in foreign meals they'd never even heard of. By the following evening, a Chinese restaurant in Manhattan had recreated the entire menu, dish by dish, for their customers.

Overnight the demand for Chinese food skyrocketed. The demand for Peking Duck — Nixon's favorite dish of the trip — went from being one of the least popular dishes in American Chinese restaurants to one of their best sellers. While most of the Chinese-American restaurants in the U.S. served largely Americanized versions of Chinese food, the Nixon-inspired boom gave Chinese chef's the chance to feature more traditional dishes, as well as test out new ideas. It's no coincidence that General Tso's Chicken appeared on the menu that same year, riding on the tails of an American wave of Sinophilia.

General Tso's isn't Americanized Chinese food, it's actually from Taiwan

Long before General Tso's Chicken made it to the U.S. menus, it was born in Taiwan at the restaurant of chef Peng Chang-kuei. A former banquet chef for the Chinese Nationalist Government, Chairman Mao's revolution forced Peng into exile in Taiwan from his home province of Hunan. Craving the taste of home, Peng began riffing on Hunanese style dishes, giving them his own spin, and making them more accessible to non-Hunanese diners.

One such creation featured crispy, chunks of breaded chicken flash fried with spicy peppers, vinegar, ginger, and soy sauce making for a tangy, spicy dish that was neither traditional nor completely unfamiliar. He called it Zuo Zongtang's Chicken — Zuo Zongtang being the full name and formal spelling of General Tso — the second most famous general from Hunan, right behind Mao, who had pushed Peng into exile. Peng claims to have named the dish when preparing it for visiting U.S. Admiral Arthur Radford in 1952. In his own way, Peng used the dish as both a tribute to a Hunanese hero and a subtle criticism of the revolution.

The original General Tso's chicken tastes a lot different than the one at your local take-out

Shortly after his death in 2016, Taiwan News published Chef Peng's recipe for General Tso's chicken, and it is strikingly different from the standard General Tso's you get from the local takeout joints. For starters, there is notably less sugar than the classic recipe we've all come to know. It is also noticeably spicier than what you might get from your local takeout joint, as many restaurants dial back the heat to make the dish more palatable to a wider audience.

Peng himself described the original dish as sour, hot, and salty. In the documentary "The Search for General Tso," chef Peng is shown pictures of takeout General Tso's, to which he dismissively waves his hand calling it, "nonsense." One can't help but note the irony of a dish that isn't even traditionally Chinese spun even further from its roots. But, then again, that seems to be the story of nearly all Chinese food in the American diaspora.

Chef T.T. Wang introduced the first General Tso's chicken in the U.S.

Perhaps one of the savviest entrepreneurs to ride the wave of the Chinese restaurant boom following Nixon's diplomatic dinners was Michael Tong. With numerous restaurants to his name, he sent his head chef, T.T. Wang, to Taiwan to recruit workers and to pick up new recipes. It just so happened he sent him at the same time as a rival New York chef, David Keh made his mecca to Peng's restaurant. Both chefs specialized in Hunanese cuisine, and Peng was the man to learn from at the time. And both returned to their restaurants with strikingly similar menus to Peng's in Taiwan, and both brought their own riffs on Zuo Zongtang's Chicken.

Tong stuck closely to the original flavor, tangy and sour, but added mushrooms, hoisin sauce, and water chestnuts. According to Salon, Wang's reinvention of the dish proved to be the winner of the day, making the chicken noticeably crispier and the sauce considerably sweeter. Both chef's restaurants won critical acclaim and 4-star New York Times reviews, but it was Wang's version of the dish that would come to be the standard General Tso's recipe eaten around the country.

Chef Peng followed his dish to the US, but everyone thought he was a copycat

In 1972 Chef Peng himself, came to the U.S., opening restaurants and making the media rounds to reclaim his title as the rightful creator of General Tso's Chicken. But New Yorkers didn't understand who he was, and he was widely regarded as a copycat. He opened Peng's on E 44th St., which was quite successful, counting even Henry Kissinger as a regular.

Peng even altered the dish to emulate the sweeter American versions. "The original General Tso's chicken was Hunanese in taste and made without sugar," Peng told New York Times Magazine. "But when I began cooking for non-Hunanese people in the United States, I altered the recipe." Jennifer 8 Lee, author of "The Fortune Cookie Chronicles," notes that Peng even tried to open a restaurant in Hunan in the 1990s, with General Tso's Chicken riding as the flagship dish, but the venture quickly closed with locals complaining that the dish was too sweet.

Just because it isn't historically Chinese doesn't make it inauthentic

Perhaps it was Chef Lucas Sin who put it best, when talking to author Francis Lam on an episode of Splendid Table. They were talking about Chinese takeout food when Sin said, "I am so sick and tired of people telling me that this Chinese food, made by Chinese Americans for the last 100-200 years is inauthentic. It's such a silly way to characterize a cuisine that spurred on generations of immigration." Sin's team did a count of restaurants registered on Yelp as Chinese and found over 46,000 across the country. "This is the second most delivered food in the U.S. after pizza, and you're just going to tell me that it's inauthentic?"

While the authenticity police might take umbrage at the very idea of General Tso's chicken, it would be disingenuous to call it inauthentic. While it may not be traditional Hunanese food as they would eat it in Hunan, it was made by a chef from Hunan. Not only that, it was made for the expressed purpose of sharing Hunanese style food with a foreigner — Admiral Radford — and even the name seems to have been Chef Peng's way of sharing his culture with his neighbors while in exile and beyond. Which — whether or not Chef Peng would approve of every version of his dish — seems to be exactly what General Tso's Chicken will continue to do for hundreds of Chinese-American chefs around the U.S.