The Untold Truth Of Heaven Hill

Kentucky is a land of stories. Spend any time in Bourbon country and you will find tall tales behind every glass of whiskey, and for good reason. Between the legacy of settlers and early distillers to the whiskey rebellion and the bootleggers of prohibition, there are heroes and antiheroes in every nook and cranny of the Bluegrass State. Big names were making big history, and more often than not, the motivation was simply because they wanted a strong drink versus the goal of making a dollar.

With all of that lore, however, it can be hard to distinguish the truth from fantasy, particularly behind the big brands with big names. Heaven Hill Distillery is responsible for some of the most reputable brands in the bourbon game and just like every major label, there are a ton of stories, rumors, and legends to sort through. Let's get down to the truth of Heaven Hill.

Heaven Hill is the largest independent bourbon maker in the world

For the casual cocktail consumer, it could be easy to think of Heaven Hill as that cheap whiskey on the bottom shelf of the liquor store, which is an easy mistake to make, since its Old Style Bourbon label is often the well whiskey at dive bars across the country. But in addition to that perfectly acceptable cheap booze, it also makes some of Kentucky's most prized aged bourbons and is one of the largest distilleries in the world.

Heaven Hill makes 19 different bourbons and whiskeys including Elijah Craig, Evan Williams, Larceny, and Old Fitzgerald. From the street driving into the distillery, dozens of white rick houses line the hill leading to the main warehouse. It is estimated that Heaven Hill produces 3.5 million gallons of bourbon per year, cranking out 1,300 barrels every day — that's 25% of the world's bourbon supply. And that's just the bourbon, the brand also produces a bevy of other boozy products from spiced rum to Irish cream.

It's also the largest distillery in the world that you can visit

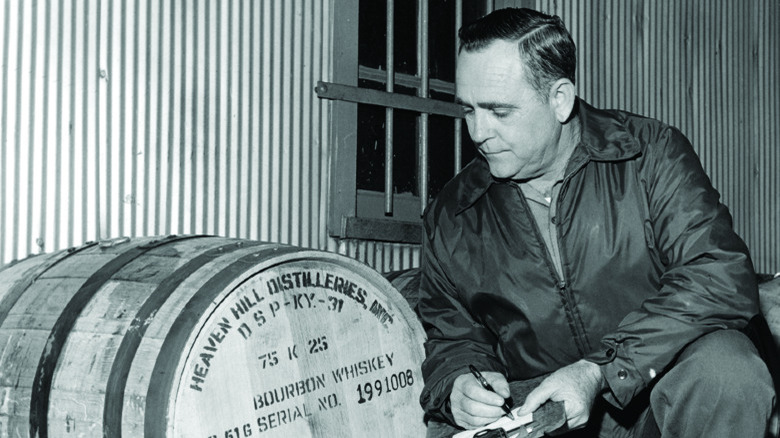

Major distilleries are massive operations. At Heaven Hill, the seventh-largest alcohol supplier in the world, they fill over 1,270 barrels every day. That takes a 500 person team to keep the stills churning and the barrels racking. But despite the massive size of the 23,000-acre facility, it's still open to the public to tour.

By now, the Bourbon Trail has attracted millions of visitors to the hills of Kentucky, and for good reason. The heritage and history there are palpable, and with so many distilleries, it can be hard to make the rounds to all of them, even in a week-long visit — believe us, we've tried. Heaven Hill offers guided tours of the distillery, interactive exhibits on each of the distillery's flagship brands, a whiskey museum, tastings that feature bottles and labels not sold outside the distillery, and even a bar offering craft cocktails.

Heaven Hill was actually founded after prohibition

When the Volstead Act was enacted in January of 1920, it set into motion a 13-year experiment in attempted national sobriety. Nearly 2,000 distilleries, 4,000 breweries, and a burgeoning wine industry were all swept under by the draconian law. Since it took a full year for the law to be enacted after it was ratified in 1919, many of the distilleries pivoted into alternative manufacturing, while just a handful of major commercial producers like Brown-Forman were allowed to continue producing for export.

When news came of the ratification of the 21st Amendment in December of 1933, the Shapira brothers saw an opportunity. Ed and David Shapira invested a sum of $17,500 and with Joseph L. Beam, created a distillery making bourbon whiskey. Since bourbon must be aged, they weren't able to start selling right away, but while the whiskey was mellowing in the barrel, they developed the brand Heaven Hill Springs Distillery, as it was called at the time.

The real meaning of the label "Bottled in Bond"

With most of America's most trusted liquor brands shuttered for more than a decade, a booming bootleg industry evolved with distillers peddling illegal hooch from stills hidden all over the country. And while a great deal of lore lingers around the quality of classic moonshine, the fact is that much of what was sold was largely rot-gut. With no oversight or regulation of the black market products, it wasn't uncommon for a bottle to poison its buyer. In fact, the Federal government even intentionally increased methanol production in commercial alcohol, a key ingredient for making bootlegged booze in the black market, to try to get people to stop drinking the banned substance.

So by the time prohibition ended, many Americans were skeptical of just what was in that bottle on the shelf. Thus the revival of the long-dormant Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897, a regulatory law passed to both ensure proper taxation of the distillers, and also to ensure the quality of whiskey produced in the United States. When a consumer saw the stamp of "Bottled in Bond" on the label of Heaven Hill, they knew it was a trustworthy product. In fact, just bearing the name bourbon is a mark of quality that sets a high bar for even the cheapest bottle on the shelf.

Heaven Hill has a close connection to another famous bourbon brand

Perhaps one of the smartest decisions made by the Shapira brothers was selecting their master distiller. There are a lot of famous families in the Kentucky distilling world, but few more famous than the Beam family, of Jim Beam. The first distiller at Heaven Hill when the brand launched in 1935 was actually Joseph L. Beam, Jim Beam's first cousin.

Mr. Joe, as he was called, had grown up in the industry, working at four different distilleries from the age of 13 until 30. When prohibition hit, he took his wife and kids with him to Juarez, Mexico, where he made tequila. But he was lured back by a job at the Stitzel distillery — of Pappy Van Winkle fame — one of the few allowed to remain open during prohibition. Following the 21st Amendment, Mr. Joe was among the first investors to back the Shapira brothers, joining the team as their head distiller.

Joseph L. Beam left Heaven Hill to become head distiller at Four Roses, and he passed the Heaven Hill baton to his son, Harry, who passed it to Earl Beam, who passed it to Parker Beam, and finally Craig Beam. For 83 years, the Beam family were the only master distillers at Heaven Hill until the mantle was passed to Denny Potts in 2018.

A massive fire at Heaven Hill once burned up 2% of the world's whiskey overnight

A fire at Heaven Hill's primary warehouse wreaked havoc on the distillery in 1996. As the structure of the primary warehouse collapsed, a flaming ocean of whiskey swept down the hill, consuming six other buildings in its path, all rick houses packed with aging bourbon, which served as fuel for the raging fire. Ten fire departments joined forces to fight the fire overnight, but as a storm blew in with winds of up to 40 miles per hour, the flames proved overwhelming and many of the firefighters abandoned their gear and ran for their lives. In the morning, the smoldering rubble was compared to a war zone by WHAS News, with the charred remains of cars and fire equipment left behind in the embers.

Four million gallons of alcohol were burned up in the fire, which was, at the time, an estimated 2% of the world's whiskey supply, and a significant portion of the bourbon made that year.

The same forensics team that investigated the Oklahoma City Bombing and the crash of TWA flight 800 were flown into Kentucky to look into the cause of the blaze. But the fire had burned up any of the evidence that could have provided clues. With no arson or foul play suspected, the cause of the fire is still simply listed as unknown.

The fire changed Heaven Hill in a big way

For over 60 years, Heaven Hill had played solely in the whiskey game, gobbling up major bourbon brands throughout its meteoric rise as one of the largest whiskey brands in the world. By the 1990s, it had absorbed Henry McKennah and a host of other Seagrams whiskeys. But the disstilery began diversifying its portfolio in the mid-'90s, and it is likely what helped Heaven Hill bounce back from that devastating fire so easily. Instead of exclusively selling bourbon, Heaven Hill now deals in gin, vodka, tequila, vermouths, and liqueurs.

With an inventory suddenly cut short by the blaze, some of the recipes began changing as the aging shifted on many of its classic bourbons, as well. Which has also likely helped the company adapt to the more recent bourbon shortages sweeping through Kentucky. As demand for American bourbons continues to rise around the world, brands like Buffalo Trace and Blantons are becoming increasingly harder to find on the shelves. But Heaven Hill seems to be riding the storm by leaning into the demanding market. The distillery has always had a wide spread of whiskeys available, and its flexibility with those products helps them stay on the shelf while still maintaining their quality.

It isn't just bourbon

That diversification of its products is wide-ranging, not just acquiring brands, but introducing and designing new products as well. In the '80s and '90s Heaven Hill acquired a wide range of labels: everything from Burnett's Gin, Admiral Nelson's Spiced Rum, Dubonnet vermouths and aperitifs, Copa De Oro Coffee Liqueur, Coronet VSQ Brandy, to Two Fingers Tequila, and Bernheim's whiskey now fall under the umbrella of the Heaven Hill brand. They also regularly launch their own new brands, like PAMA Pomegranate Liqueur and O'Mara's Irish Country Cream.

Many of those spinoff products also have cult followings of their own, like the hipster Mellow Corn Whiskey. Unlike bourbon, which is only required to have up to 51% corn and aged in charred barrels, corn whiskey can be upwards of 80% corn and is usually aged in barrels that have not been charred, which makes for an easy drinking, light-bodied whiskey.

Lunazul Tequila has also garnered a cult following, earning a reputation for being one of the best quality value tequilas on the market, made from 100% agave. And why wouldn't Heaven Hill have one of the best tequilas out there? After all, founder "Mr. Joe" Beam was a master tequila distiller in Mexico!

The law-breaking preacher who invented bourbon

Long before Heaven Hill was even conceived in the minds of the Shapira brothers, Elijah Craig began distilling in Kentucky. The story goes that Elijah Craig was a preacher who had been arrested at least twice for preaching without a license in Virginia in the 1770s. Craig spent time in both Kentucky and Virginia, the latter, of which required preachers to receive a license from the Anglican church in order to preach. Craig being a fiery Baptist preacher continued preaching, shouting from the windows of the jail to the crowds outside. Tasked by his church governing body with proselytizing communities along the James River, Craig moved to the region where he founded the forerunner for Georgetown College, built a paper mill for the local newspaper, and began distilling whiskey.

While much of the lore around him seems dubious, at best, Craig is widely credited with the invention of bourbon. The legend goes that a fire in one of Craig's barns charred a barrel. Being a thrifty man, he still used that barrel when racking his whiskey and found that it mellowed the liquor quite elegantly, so he began the practice of scorching his barrels. This fable came in quite handy for those pushing against prohibition in the 1910s, as they had the shining example of the Baptist minister, settler of Georgetown, and the founder of a Baptist college to hold up as the father of bourbon whiskey.

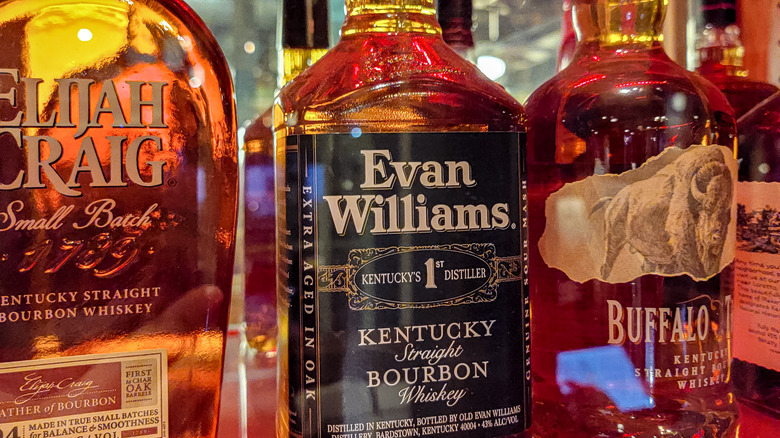

Was Evan Williams really Kentucky's first distiller?

There should be no understating that lore and legend are of far more value than historical accuracy when it comes to bourbon; tall tales are part of the fun. According to the scrawl on their famous black label bottle, Evan Williams was Kentucky's first distiller, firing up his still in 1783. But historians debate if it is true. In his book, "Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey: an American Heritage," historian Michael R. Veach notes that the claim of Evan Williams as Kentucky's first distiller did not appear until a publication by Reuben Durrett more than 100 years later. Records actually show Williams traveling from London to Philadelphia in 1784, much later than the Evan Williams bottle claims. Williams, himself, made plenty of history in his own time, whether he was or wasn't the father of Kentucky distilling. He served in several elected and official positions before and after Kentucky became a state.

While we may never know the identity of the first distiller in Kentucky, since record keeping wasn't exacting at the time, it is worth noting that Jacob Myers was already giving away his own whiskey to promote his run for office on election day in 1781, two years before the claim of Evan Williams. Isaac Shelby, Kentucky's first Governor, was also a distiller, following in the footsteps of his father, Evan Shelby, who settled the area that is now Bristol, Tennessee, and made whiskey for settlers heading west.

The Jewish origins of Kentucky whiskey

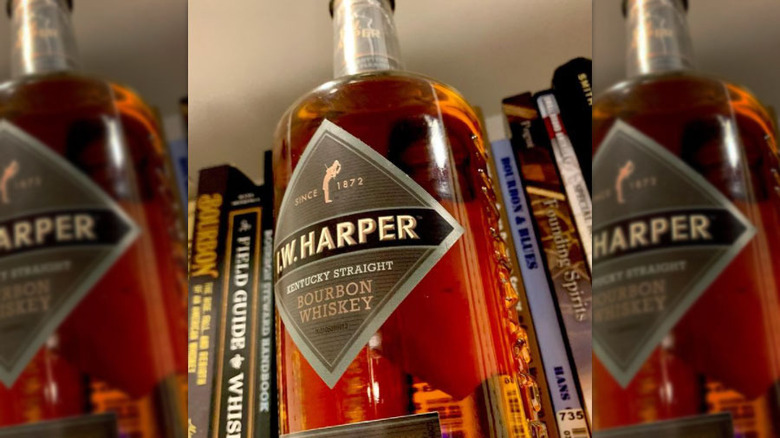

It made perfect sense when Heaven Hill acquired the Bernheim distillery, after all, why wouldn't a brand known for preserving the legacy of historic distillers invest in one of the most underrepresented whiskey stories of them all? In 1872, Isaac Wolfe Bernheim, concerned over the rampant anti-semitic sentiments in his newfound homeland, used his initials and adopted a more European moniker when he founded I.W. Harper Bourbon (via The Atlantic). It is said that the scant minority Jewish population — just 3% — comprised a whopping quarter of the whiskey trade in Kentucky in the late 1800s, a legacy lost in much of the lore from that era. The anti-semitic attitudes in the U.S. were so clear at that time that even Henry Ford, an ardent supporter of prohibition, felt comfortable proclaiming that distilling was "one of the long list of businesses which has been ruined by Jewish monopoly."

Bernheim died in 1945 at the age of 96, but his bourbon far outlived him. By 1966 it was available in 110 countries around the world. The company eventually shuttered following a decades-long pivot away from American bourbon in the public through the '60s and '70s. By reintroducing Bernheim's Whiskey over 120 years later, Heaven Hill pays tribute to an even more storied history, one that includes Jewish immigrants like Isaac Wolfe Bernheim, who brought his tradition of distilling across the Atlantic in 1867.