The Untold Truth Of Simone 'Simca' Beck

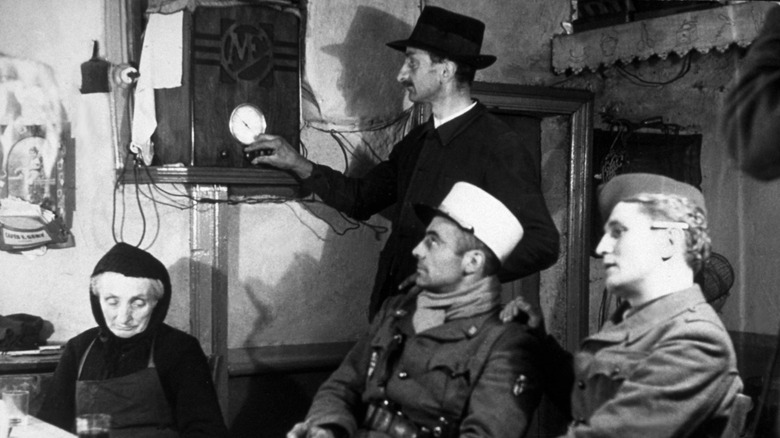

Julia Child may be the chef most closely associated with the famous cookbook, "Mastering the Art of French Cooking," but it was hardly a solo endeavor. One of her co-authors (as portrayed in the 2009 movie "Julie & Julia" — seen above — by actress Linda Emond) was Simca Beck. Born Simone Suzanne Renée Madeleine Beck in 1904 in Dieppe, Normandy, Simone Beck would go on to have an enormous and consequential influence on the kitchens of mid-20th century America (via Hazlit). Best known as Julia Child's collaborator on their seminal work "Mastering the Art of French Cooking," "Simca" had a much lower profile than her more famous partner. Her aristocratic upbringing helped shape her into a strong-willed and imperious woman. She was convinced of her own unimpeachable taste and had no problem letting others know it.

Throughout her long life, Simca weathered many storms, from the catastrophe of Nazi occupation to navigating a loveless marriage. Her experiences shaped her into a woman who was unafraid to defy the customs of her class and sex as she pursued satisfaction, both professionally and in her relationships. Julia Child may be more famous, but some people argue that she wouldn't have gotten anywhere without her "French sister" by her side.

She grew up in with a silver spoon in her mouth

Simone Beck grew up in the French province of Normandy, known for its rich diet of butter, cream, cider and seafood, according to Explore France. Beck grew up eating the traditional dishes of her home region, including heavy seafood soups. Loaded with shellfish from the adjacent Atlantic and cream from the vast herds of cattle raised on the fertile plains of Normandy, Marmite Dieppoise is a great example of this local cuisine.

Part of the traditional eating habits of Normandy include ritual called the "trou normande" or a Normal hole, this is a shot of potent Calvados – an aged apple brandy — thrown down in the middle of the meal. It's called a hole because it's meant to make more room in the stomach in the middle of a copious, high-calorie feast.

The rest of France drinks wine, but here the cider flows (per Cellar Tours). Beck described how a jug of lightly fizzy, dry cider was always present on the dinner table. Often this cider is cooked into the dishes of the region, the same way wine is in — for example — Burgundy. This legacy of growing up in Normandy followed Beck throughout her life and she drew on the inspiration of these family dinners in all of her cookbooks.

Her family's fortune came from the liquor business

Beck's family's wealth came from her grandfather's discovery of the recipe for an ancient liqueur called Bénédictine. This recipe dates back to a monastery formula for a medicinal drink infused with various botanicals and imported spices — an extremely precious commodity at the time. Evidence places the beginning of this tradition all the way back in 1510. It is still produced to this day.

It usually is served as an after-dinner drink, in small delicate glasses. It is wise to pour it in small amounts since it is particularly sweet and particularly strong -– at 40% alcohol, it's as potent as straight vodka. A common way to consume it is mixed with an equal amount of brandy, a ratio that helps temper the sweetness. This is such a popular habit that the company now sells it premixed under the name B&B. Other famous uses for it include classic cocktails like the Singapore Sling and the Vieux Carré

Beck had an affinity for this family heirloom all her life and many of her dessert recipes suggest using it to flavor various custards and soufflés.

Simca Beck was determined to cook no matter what

Despite the hired help her family employed, Simca Beck began to teach herself how to cook and kept herself busy by inventing recipes that she fed to her grateful family. She especially loved cooking the wild game that her family hunted for — something common among upper-class European families going back thousands of years (per MIT). From a young age, Beck would pester her family's cook, a talented woman named Zulma, to teach her all she could.

In her autobiographical book "Simca's Cuisine," she describes how some of her earliest memories were of the extravagant picnics her parents would host. These were typical of the time period in the early 1900s according to Food Timeline. They would drink lots of Champagne and be served elaborate finger food by the servants they had brought along on their outing.

One particular area Beck was always interested in was cake making. She loved to invent new recipes, often refining the same recipe over and over till she was satisfied it was perfect — a habit that would serve her well in the future when she tested recipes for publication. This is also something that would endear her to her second husband who loved chocolate desserts above all others.

She married young to a rich business man

Simca Beck followed the path laid out by her family and was married at just 18 years old. His name was Jacques Jarlaud. At first, she was complacent in her upper-class life of bridge and ladies luncheons — though such a life eventually would bore vivacious and intelligent Beck to tears.

Her husband was shorter than the statuesque Beck and she quickly found herself repulsed by him, describing him in her book "Food and Friends" as the "unprepossessing equivalent of a frog." She went through the motions, but she found that she wanted something more than a comfortable life, according to Hazlit. When she discovered that they could not conceive children together she sank deeper into a funk, finding even this "normal" accomplishment out of her reach.

Desperate for something to bring some meaning into her life she cast about for distractions. The most promising — and enduring — was letting herself cook. Ladies of her social status were expected to supervise a paid cook who would take care of the hard work of actually producing meals, but Beck was not one to be deterred by a little thing like class expectations. She found the kitchen an escape from the dullness of an unfulfilling existence.

A catastrophic car crash changed her life

It took a 1928 near-fatal car accident for Beck to snap out of her complacency. After such a wake-up call, she made the rare move for a lady in the time period and divorced her husband — something women had won the right to in the French Revolution of 1789, per Ohio University. Such a drastic move would have shocked her conservative father, had he not died of leukemia — perhaps something that gave her enough of a push to finally call it off. Beck was devastated by the loss of her doting father and she refused to wallow in a marriage that made her miserable.

Beck didn't need the money, but briefly turned to bookbinding as a profession to fill her time. However, still finding herself unfulfilled, and determined to find something she truly cared about, she ended up enrolling at the famous Le Cordon Bleu cooking school in Paris.

This was especially surprising considering her upper-class upbringing — most of the students at the time were hardened professionals and grizzled war veterans. Some American soldiers learned here on the G.I. Bill (per Funding Universe) — looking for a life to settle down into after aging out of the army. This formal training allowed her to focus on improving her skills in the kitchen. Le Cordon Bleu also connected her with other food enthusiasts — some alumni, some just wealthy hangers-on, eager to scout the best places to get a good meal.

She met the love of her life in Paris

While living in Paris in 1937, Beck met Jean Fischbacher, a younger, debonair perfume manufacturer. Fischbacher swept her off her feet and Beck finally felt a sense of euphoria, something she had not come to expect out of her life. They were crazy about each other and Jean saw her as his equal, someone with whom he could share all the pleasures that life had to offer. He was the one to nickname her "Simca" after her tiny little car.

Simca Beck, by no means a feminist, insisted on keeping her maiden name for professional purposes. She took — and used — Fischbacher's last name socially, but she was known to her eventual audience by the Beck name, something she was particularly proud of.

After they married, the two food lovers would host friends and family for elaborate dinner parties, where she would proudly present her finest dishes including professional-level feats of sauce making and pastry work — the product of her own skills and ingenuity as much as her professional-level education from le Cordon Bleu.

Beck's husband was held captive during WWII

Jean Fischbacher enrolled in the French army to fight the Nazis in WWII. When France surrendered, he was placed in an internment camp. Meanwhile, Beck's family estate in Normandy was taken over by German officers and she and her aging mother were forced to share their living space. She would barter her family's stash of Bénédictine for extra wartime rations to send to her husband, and recount these harrowing stories in her book "Food and Friends." She also revealed how her family closed up their wine cellar behind a false wall as the Germans approached — something that happened all over France, per Decanter.

Once Fischbacher was liberated he and Beck were reunited while the rest of France recovered from its humiliating defeat. Despite the supplies of food she had sent him, he came home terribly malnourished and had trouble with the rich food they were used to eating together. She treated him to nutritious but gentle bouillons that she could once again find the ingredients to, as France picked itself back up again, quite a change from the privations brought on by occupation, according to Secret Food Tours.

Swept up in the postwar bliss of being reunited, Beck and her husband fell into their old habits of savoring meals and she joined the exclusive ladies' society eating club Le Cercle des Gourmettes. She was drawn to one fellow member in particular, a social butterfly who shared her enthusiasm for food named Louisette Bertholle.

Simca Beck met and bonded with Julia Child in Paris

Meanwhile, Julia Child had moved to postwar Paris with her diplomat husband in the 1950s and, after becoming enamored with French food, she fell in with other enthusiasts — including Beck, Bertholle, and le Cercle des Gourmettes. Similar to Beck, Child found herself unsatisfied with an easy housewife's life and had even found her way to the same cooking school, le Cordon Bleu. In her book, "My Life in France," Child describes her cooking mentor Max Bugnard giving the ladies' group demonstrations complete with a catered lunch.

The three women began a small cooking school that specialized in demonstrating the fundamentals of French cooking to American women who were visiting Paris and wanted to soak up some culture. They called it l'Ecole des Trois Gormandes or the School of Three Hearty Eaters. Julia would go on to wear a patch sewn with this name on her future show.

Beck had been working with Bertholle on a book on the fundamentals of French cooking aimed at an American audience. Although they had strong mastery of the subject and Bertholle was particularly well connected, the book wasn't finding any traction. When they met Child, it soon became clear that she was the perfect "secret ingredient." As an American, she had insight into what was feasible and familiar to their intended audience. It wasn't long before Child was pulled into Beck's project (Chicago Tribune).

The book took many years of letter writing correspondence

The book that the three women wrote was an enormous undertaking. Their magnum opus was the incredibly influential two-part "Mastering the Art of French Cooking." In it, they demystified French cuisine for readers and pulled back the curtain on how many classic dishes were prepared, even if some of them were a bit complicated.

The process of thorough testing that they insisted on for each recipe meant that the huge book came together very slowly. Child's husband, Paul Child, an American diplomat, was reassigned, first to Marseille — in the south of France — and then to Norway and Germany. Therefore, much of the actual writing and back and forth correspondence was done remotely, as Beck and Child tirelessly tested recipes and assiduously took notes and mailed them back and forth,

When the book was released, it was an instant phenomenon. No other English book at the time spoke with such detail and authority, patiently guiding a beginner through the intricacies of cooking French food. The cuisine and culture of France was particularly en vogue during the time period and a curious and receptive audience bought out each successive printing of the book. It remains in print to this day and the Telegraph named it the second best cookbook of all time.

The women joined the nascent food scene of the time, populated by the likes of the New York Times' influential restaurant critic Craig Claiborne and the endlessly knowledgeable James Beard.

She was considered the ultimate French woman

Throughout their collaboration, Julia Child always regarded Beck as the quintessential French woman. This was not always meant as a compliment. Child associated stubbornness with French people and she saw this trait exemplified in Beck. She was perpetually convinced that her way was the only way. She was the ultimate authority for all things French and she often declared things "unfrench", something that — to her — was the worst insult she could think of, per her New York Times Obituary.

Her uncompromising nature endeared her to several food purists, and late food writer Richard Olney wrote — in his own memoir "Reflexions" — with relish about visiting Beck and her husband at their home in the south of France and the meals they would prepare together. Every meal was finished with a rich chocolate cake — always a different recipe — because that was her husband's favorite.

She and Child collaborated on a second volume of "Mastering the Art of French Cooking" that expanded upon and took a deep dive into several French specialties; the recipe for French bread alone took up 22 pages. Although the book was well received and was another exceptionally well-researched project, it marked the end of the professional collaboration between the women. The frayed nerves from the second project of this magnitude were enough to cause Child to swear off any more work with "La Super Française" — a title that roughly translates to the Ultimate French Woman.

Her celebrity never equalled her writing partner's

Although Beck provided many of the recipes and techniques that endeared the two of them to the American public, she never earned the same celebrity that Julia Child did. However, the two women remained close, calling each other "sisters." In fact, Child and her husband had made an arrangement with Beck and Fischbacher for a tiny sliver of their estate — called Bramafam — where Julia and Paul could build a small Provençale cabin which they labeled la Pitchoune — or Tiny Little Thing.

Beck, feeling left out and marginalized when she realized what a household name Child had become, arranged a photoshoot at her estate to which she insisted her collaborator come. Child found herself less than willing and the tension caused a small rift between the two women. Despite such differences, the two remained friends for life and exchanged an enormous number of letters back and forth, many of them bursting with ideas and stray thoughts on new recipes and variations.

She taught cooking classes in the South of France that attracted international students, but she didn't have Child's exposure to an American audience thanks to her television show "The French Chef." Beck, although she spoke perfect English, was uncomfortable in front of the camera and when she appeared in an episode, she came across as cold and demanding — in direct contrast to the natural warmth that Child showed on camera.

She stayed as busy as ever as she aged

Beck never slowed down and she continued to publish books, putting her personal spin on French cuisine. Judith Jones, the editor who had taken a chance on Beck and Child's original manuscript, continued to work with Simca. She encouraged her to write herself into her work.

Such was Beck's work ethic that she was discovered at her home in the South of France stuck on the ground with a broken leg. Unconcerned about the pain, Beck was most annoyed at the inconvenience of not being able to bounce around the kitchen and had actually used her shoe to knock one of the bones back into alignment. When she recounted this tale to close friends, they were appalled — but not surprised. After all, it was perfectly in line with her standard mode of utter determination and single-mindedness.

Each book she produced during this time was brimming with personal anecdotes and stories from her long and fascinating life. The recipes that she produced were often drawn from the provinces of France that she and Fischbacher had lived in, including the traditions of Normandy, his family home of Alsace, and the Provence where they settled together at Bramafam. She was as thrilled with the rich, cream-based cuisine of her youth as she was with the Germanic-inspired Alsatian food and Provence's famous sun-soaked Mediterranean fare. To the end, she remained opinionated and endlessly curious.

She kept publishing cookbooks until the end

Part of her happiness was snuffed out when her beloved Jean passed away in 1986. With his passing, Beck tried to keep herself occupied and published one more book. This one, "Food and Friends," was equal parts recipe book and memoir and, in it, the typically reserved Beck shared the most personal and foundational stories about herself. She recounted a full lifetime of good food, cooked for and enjoyed by loved ones the world over. The tremendous effort she put into this book — she refused to compromise on the thorough testing and research that she submitted all her books to — caused a great strain on an aging Beck.

She found herself unable to attend the premiere party for the book and passed away soon after, at the age of 87, from heart complications. She left behind a legacy of detailed and authoritative books on her favorite subject and cemented her place as an icon of the food world. Although her business partner and friend, Julia Child was much more famous and well-known among the general population, Simca Beck had an incalculable effect on food culture in both the United States and France. Her steady, uncompromising hand left a strong impression on those who were able to learn from her lifetime of experience in cooking traditional French food.