The Untold Truth Of Cajun Food

We can't find any statistics for this, but we'd wager that Cajun cuisine is one of the most misunderstood types of food in America. We've lost count of how many times we've seen an insipid tomato soup passed off as gumbo or had someone try to sell us fettuccine Alfredo with some cayenne in it as Cajun pasta. The further you get from the heart of Cajun country in rural Southern Louisiana, the more likely you are to get watered-down approximations of the real thing (even in New Orleans).

That's a shame because Cajun food is one of America's truly great regional cuisines. Nothing else tastes quite like it, and it's a celebration of the bounty of produce, seafood, and meat available in Cajun country. If you can't book a trip down to Lafayette, you can at least learn the history of this incredible cuisine. You'll see that the story is almost as rich and complex as a real Cajun gumbo.

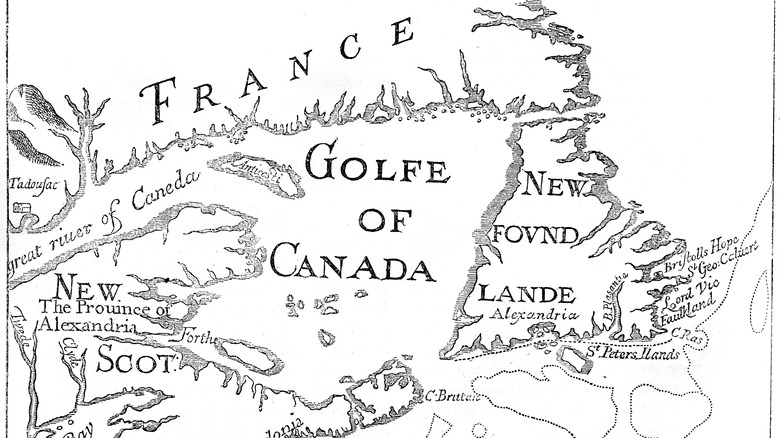

Cajuns emigrated from Canada to Louisiana

Any discussion of Cajun food must begin with some background about who Cajun people are. The word Cajun stems from the French term Acadien used to describe people from Acadie. Before moving to Louisiana, the people who became Cajuns resided in Acadie, a region in Nova Scotia, Canada (via Lafayette Travel). According to the National Park Service, immigrants from Vendée in Western France started arriving in Acadie in 1604. Eventually, around 18,000 Acadians settled in the area ruled by the French.

The English took over that part of Canada in 1713 and had trouble governing the French Acadians, who didn't want to pledge loyalty to the British government or convert to the Church of England. In 1755, all the Acadians were expelled from Canada, an event known in Cajun history as Le Grand Dérangement. They moved to a variety of different places, but many settled in South Louisiana after 1784 when the King of Spain officially allowed them to live there. The displaced Acadians brought their language and culture with them to the region and created the food traditions we associate with Cajun cuisine today.

Cajun food is rural cuisine

Acadians lived a rural life, both in Canada and in Louisiana. They had to be resourceful and cook creatively with the supplies the land offered them. In Acadia, that meant seafood like lobster and fish (via Global Foodways). Per the National Park Service, once Acadians settled in Lousiana, some made their homes in swampy bayous and others lived in Southwestern Louisiana's prairies. On the prairies, they were able to grow rice and maintain cattle ranches. Whether in the bayou or on the prairie, Cajuns started working with a completely different set of ingredients than they were used to in Canada.

They cooked local ingredients like corn, mirlitons (aka chayote squash, considered by The Kitchn to be New Orleans' unofficial squash), crawfish, and alligator. Cajuns had to be resourceful by fishing and hunting, in order to make a living and keep themselves fed. This sense of thrift is expressed in traditions like the boucherie, a traditional hog-slaughtering event where every single part of the animal is used in some way, according to HuffPost.

It has French, Spanish, African, and Native American influences

The basic techniques in Cajun cuisine are rooted in the French traditions of the first Acadian settlers. However, this isn't fine-dining French food we're talking about. As we mentioned, Cajun cooks prepared humble country cuisine. As Grapes and Grains describes, Cajun food is based around locally available ingredients cooked in a simple, honest way.

The Acadians were just one of the groups who influenced what eventually evolved into Cajun cuisine as we know it. Jambalaya is a descendent of the Spanish dish paella that dates back to the period when Spain ruled Louisiana (via Chowhound). Creole cooks in New Orleans swapped out Spanish saffron for American tomatoes. When the dish arrived in Cajun country, it lost the tomatoes and became brown.

Gumbo is another dish that shows the multiple influences that shaped Cajun cuisine. As Atlas Obscura explains, one of gumbo's classic ingredients, filé powder, is made from the indigenous sassafras tree and was used by Native Americans long before European colonists arrived. Meanwhile, okra was brought to the region by enslaved Africans. The use of local seafood like shrimp and crawfish also owes a debt to the influence of indigenous people.

Eating crawfish is a Cajun tradition

Crawfish have been an important food source for people in Louisiana since before recorded history. The Native American Houma tribe used the image of a crawfish as their symbol (via Deanie's Seafood). Once the Acadians arrived, they began eating crawfish as well. This was mainly because the mudbugs were plentiful and a good source of cheap meat, but the critters also worked well in the lobster recipes Cajuns brought with them from Canada, according to Jefferson Chamber. However, until the 20th century, many people thought of crawfish as a poor man's food, and they didn't become widely popular until Creole chefs in New Orleans introduced them to urban customers.

These days, large communal crawfish boils are popular all over Louisiana, and even in neighboring areas such as Houston (via Houstonia Mag). Spring is the traditional season for crawfish because flooding forces them to come out of their burrows, making them easy to catch. Crawfish season happens to coincide with Lent, a period during which Catholics aren't allowed to eat meat on Fridays (fish is okay). We can't imagine a more indulgent Lenten feast than a big pot of crawfish.

Cajun food is not Creole food

If you're not from Louisiana, you might be forgiven for thinking Cajun and Creole food are the same thing. To be fair, they are very similar and use many identical ingredients and cooking techniques. A number of dishes including jambalaya and gumbo exist in both cuisines. However, Cajun food and Creole food are not the same.

A lot of the differences between the cuisines come down to the cultural backgrounds they emerged from. As we discussed, Cajun food comes from rural traditions. It tends to be heavier and heartier and uses a simpler seasoning profile. Creole food, on the other hand, developed in New Orleans. It is more influenced by the haute French and Spanish cuisines of wealthier settlers and uses a greater amount of butter and herbs compared with Cajun food (via Grapes and Grains).

Over the years, the two traditions have blended together so much that it can be hard to say whether a specific dish is purely Cajun or Creole. One telltale sign is whether or not tomatoes are present. In general, Creole food uses a lot of tomatoes, whereas Cajun food tends not to include them, according to the New Orleans tourism website.

Fans of spice will love Cajun seasoning

A very common way for home cooks across the U.S. to add a little Louisiana flair to meals is by reaching for a can of Cajun or Creole seasoning. On the Creole side, perhaps the most notable brand is Tony Chachere's. For Cajun flavor, you might choose the entertainingly-named Slap Ya Mama. Much like the Cajun and Creole food traditions they come from, these two spice blends are very similar to each other, but they do have subtle differences.

Both Cajun and Creole seasonings start with a base that usually includes black pepper and cayenne. MasterClass explains that Cajun blends tend to stick with the pepper theme, often including white pepper and paprika. The flavor is usually rounded out with onion and garlic powder. It's typically spicier than Creole seasoning, which incorporates herbs like oregano, thyme, and basil. The complexity of the herbs reflects the cosmopolitan roots of Creole food.

Despite the slightly different formulas, you can feel free to use Cajun seasoning in place of Creole and vice versa. Just know that the Cajun stuff will probably be a bit spicier and less herbaceous than its cousin.

A holy trinity forms the base of many Cajun dishes

One of the secrets to learning how to cook authentic-tasting food from any tradition is mastering the cuisine's signature flavor base. In French cuisine, the classic mirepoix of onion, celery, and carrot shows up over and over again. Cajun food has its own trio of signature ingredients, but even though the cuisine is heavily indebted to French traditions, it doesn't use the standard mirepoix. In Louisiana, cooks swap out the carrots for bell peppers (via LSU Ag Center).

It's not entirely clear why this switch happened, though it could be because bell peppers are native to the Americas, while carrots are an old-world crop. As far as we're concerned, carrots in gumbo would just taste weird. Countless Cajun recipes, from crawfish etouffee to gumbo and jambalaya, start out by sauteeing the trinity. This flavor base has been used for quite some time, but the name itself was coined relatively recently; Chef Paul Prudhomme started calling the celery-pepper-onion trio the holy trinity in the 1980s (via LSU Ag Center).

A Cajun boucherie is a whole-hog party

As we alluded to earlier, a boucherie (French for butchery), is the Cajun term for slaughtering a hog. In the days before refrigeration, the point of a boucherie was to preserve every part of the animal before it went bad so you could eat meat throughout the year. Now that this kind of old-fashioned meat preservation isn't necessary, a boucherie is more like a big meat-centric communal party. One thing that hasn't changed is that every single piece of the pig, from tail to trotter, gets turned into something edible (via Texas Monthly).

The Cajun food tradition is filled with preparations that use underappreciated cuts of pork. Organ meats get turned into boudin, sausage, stew, and a stuffed-stomach dish called ponce. Skin and fat are rendered down into lard in a huge cauldron, with the leftover solids crisping up into delicious cracklins. Even the head is transformed into head cheese. It's a celebration that can bring a whole community together, and it's a great way to eat an animal while producing almost no waste.

Cajun boudin is a sausage like no other

One of the products of a boucherie and among the best-loved foods in Cajun country — boudin — deserves further discussion. It comes in two forms: boudin noir (which is made with blood) and the more popular boudin blanc (via Acadiana Table). Boudin blanc is a mixture of pork meat, pork liver, white rice, and seasonings, stuffed into a sausage casing and then steamed. It's very soft and luscious, and one of the most popular ways to eat it is to simply squeeze the filling out of the casing into your mouth, according to Louisiana Travel. If you want a little more texture, it's also common to find boudin rolled into balls and deep-fried.

The city of Lafayette made a website called The Cajun Boudin Trail that lists all the best spots to buy boudin in Cajun country. These stores also tend to sell other Cajun meat specialties like cracklins, sausages, and stuffed chickens. A Cajun butcher shop is a true carnivore's paradise.

Dark roux is essential for Cajun food

Cajun food has a complex deep flavor despite the fact that it's often made with simple ingredients. One reason for this is that the cuisine has not one, but two flavor bases. In addition to the previously discussed holy trinity, many dishes also start with a roux, usually a dark one. Often the roux is combined with the trinity, as in our recipe for seafood gumbo (take out the tomatoes if you want it to be more authentically Cajun).

According to The Spruce Eats, both Cajun and Creole cuisines use roux, but not the same kind. The Creole version is more French-inspired and is made with butter. Since butter burns at high temperatures, this roux is only cooked briefly. Cajun roux, on the other hand, is made with lard or neutral oil and tends to be cooked until dark. Light roux is useful primarily as a thickener, but dark roux adds flavor to a dish from the toasted flour.

Opinions differ about how dark to cook roux. Real Cajun Recipes says to heat it until it's penny-colored, whereas Acadiana Table advocates for a roux that looks like melted chocolate. You have to be brave to cook it that dark, as it's only a step away from being burned at that point.

Cajun gumbo is meaty and thick

As Serious Eats notes, gumbo isn't really one single dish, and every cook makes it a little bit differently. It can vary widely in its consistency, what kind of vegetables are used, and the choice of proteins. The only constants are that it usually starts with a roux and is thickened with either okra or filé powder (or sometimes both).

That said, Cajun gumbo has some common features that set it apart from its Creole counterpart. For one, in keeping with Cajun food generally, it skips the tomatoes. According to Cleveland Magazine, Cajun gumbo is usually made with a darker roux and has fewer chunks of vegetables and a thicker texture than Creole gumbo, which is soupier. Meat is another area where Cajun gumbo sets itself apart. While it can certainly contain seafood, it's more typical to use chicken, sausage, and ham in Cajun gumbo. Meanwhile, the Creole version tends to be more seafood-heavy (via The Gregory).

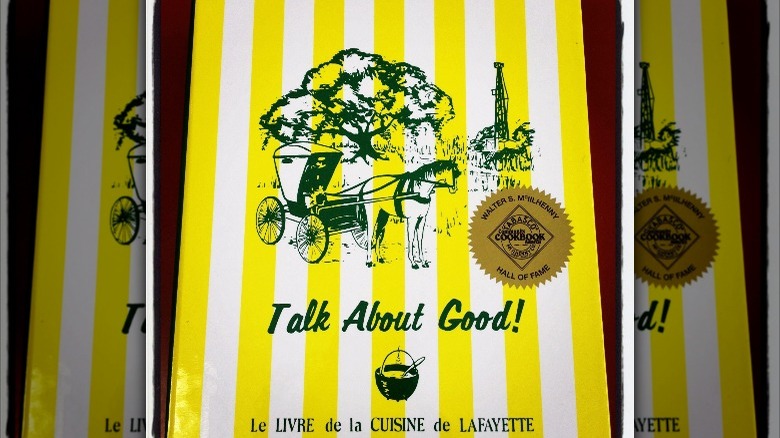

A community cookbook is the definitive collection of Cajun recipes

As befits a tight-knit community like Cajun Louisiana, perhaps the most notable record keeping their food traditions alive is a community cookbook written by regular people. "Talk About Good!" was compiled by the Lafayette Junior League (a women's volunteer organization) in 1967. It's still in print and has sold more than three-quarters of a million copies since it debuted. That's a shocking success for an amateur cookbook and a testament both to its important place in Cajun culture and the quality of the recipes inside.

The Washington Post writes that "Talk About Good" often takes on heirloom status in Cajun families, with battered food-stained copies being passed down from one generation of home cooks to another. One secret to its success might be that it has never changed. Every recipe in the book is exactly the same as when it first came out, making it a valuable historical document that captures what Cajun people really cooked at home in the mid-20th century.

Chef Paul Prudhomme helped popularize Cajun food

No one person did more to popularize Cajun food in America than the late Chef Paul Prudhomme. These days, you might know him as the smiling face gazing from spice mixes on a supermarket shelf. However, starting in the '70s he revolutionized Louisiana food, becoming perhaps the most famous chef in America in the process (via Eater).

According to The New York Times, before Prudhomme got involved, Cajun food was relatively unknown even in New Orleans, just an hour or two from Cajun country. Prudhomme got a job as the chef at Commander's Palace, a venerable old Creole restaurant in New Orleans, and began adding Cajun dishes he remembered from his youth in rural Opelousas, Louisiana to the menu. He later branched out into his own restaurant, K-Paul's Louisiana Kitchen. He was able to synthesize both strains of Louisiana cuisine into a hybrid dubbed Haute Creole.

One Cajun dish he helped popularize was blackened redfish. Blackened fish is common now, but that's only because Prudhomme's original take on the idea spread across the nation like wildfire. It became so popular that it actually had a negative effect on the redfish population (via Eater). If you want to taste a little bit of Prudhomme's legacy, try our recipe for blackened fish sandwiches (but use sustainable fish, please).