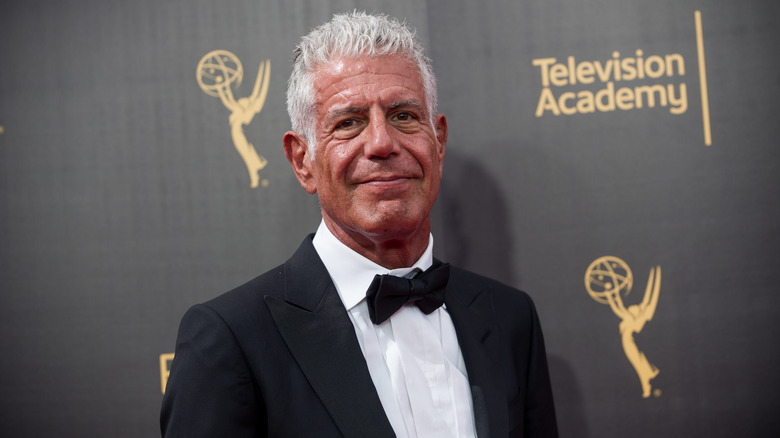

The Transformation Of Anthony Bourdain

"I think of the film as therapeutic," Morgan Neville, director of the Anthony Bourdain documentary "Roadrunner," said to Condé Nast Traveler. "The film itself is a way for us all to process what happened to this guy we thought we knew."

Three years have passed since Bourdain's death by suicide, and yet the pain remains fresh for many, even those not personally connected to him. Just as notable is the fact that Bourdain became so beloved and so central in a relatively short amount of time. Between his bombastic entrance into public life with the publication of "Kitchen Confidential" when he was 44 and his death at 61, he had just under 18 years to transform from a reasonably successful chef into a household name into a cultural icon. The trajectory almost fit together better than any actual story Bourdain wrote. That is in part because the public character of Anthony Bourdain was Bourdain's greatest creation.

Bourdain appeared on America's public radar as a pre-fabricated vagabond chef with stories to tell and dark secrets to share. While he made no attempt to hide his background, Bourdain's swagger, infused with the aura of a recovering addict, shook off memories of his relatively privileged upbringing.

Born comfortable

Bourdain told Patrick Radden Keefe in a live interview (via YouTube) how his mother helped him get his essay "Don't Eat Before Reading This" published in The New Yorker because she knew someone there. As Bourdain explained to The Guardian, she was a copy editor for The New York Times, while his father worked as a record executive in the 1970s.

He even wrote with disdain about his background. "I went to a private school a tweedy institution where kids wore Brooks Brothers jackets with the school seal and Latin motto (Veritas fortissima) on the breast pocket," Bourdain sneers towards the end of "Kitchen Confidential," where he admits the differences between a non-excellent chef like himself and Scott Bryan, a cook of the first order. "I, a product of the New Frontier and Great Society, honestly believed that the world pretty much owed me a living — all I had to do was wait around in order to live better than my parents."

Part of this upbringing consisted of a month-long vacation to France to visit his father's family, recounted in "Kitchen Confidential." Between reading Tintin comics, his parents would try to drag him to French restaurants where, as the picky eater he was, he'd refuse to comply and thoroughly embarrass them. This continued until they left him and his brother in the car while they dined at Le Pyramide, "the center of the culinary universe."

An oyster changed Anthony Bourdain forever

Put out by this move, Bourdain decided to not just eat everything, but to show gastronomic daring by eating almost any food. Everything changed when he ate a fresh, raw oyster. "This," he remembered, "was the magic of which I had until now been only dimly and spitefully aware. I was hooked." However, as he admitted to The Guardian, the pursuit of ever more adventurous tastes was less about exploring new foods and more about other people's reactions. And food offered adventure.

"He liked to be called a writer," Morgan Neville told Mashed in an exclusive interview, "and I think he really fundamentally saw himself always as a storyteller, and he wrote a lot." Bourdain himself had originally wanted to produce comics, but, as Vulture notes, he couldn't draw.

Even though "Kitchen Confidential" is often seen as the starting point of Bourdain's literary career, he had already written and published two crime novels prior. This genre, Thomas Wickersham explains in Crime Reads, lends itself the best to the types of travel shows that followed the success of "Kitchen Confidential." "Crime authors claim ownership of a city by shattering its polished facade and revealing the ugly truths lurking in the shadows," he writes. "They take readers on a ride through society's margins: cops, gangsters, misfits, addicts, and the lifelong losers who can't catch a break."

Bourdain failed into kitchens

Similarly, as Bourdain grew more confident with his shows, they turned from simply showcasing food to pulling back the curtain covering the real world behind the vistas. Even in the first episode of "A Cook's Tour," when he lands in Japan, Bourdain naturally found himself investigating the edges of the secret world of sumo wrestling. He was a writer at heart.

As Bourdain would often claim, the kitchen was the last refuge for the criminal minded, the misfits, and other types who could not handle the rigors of polite society. Bourdain stumbled into that world during a summer vacation between his second year at Vassar and what should have been his third. He was vacationing in Provincetown at the expense of a few roommates, when one, tired of footing the bill, got him a gig as a dishwasher.

"It was really a big event for me because up to that point, I was lazy," Bourdain would later tell NPR. However, the kitchen forced him to conform to some basic rules, such as punctuality. "And for whatever reason, I responded to that. It was a mix of chaos but also considerable order that I guess I needed at the time."

That order also came at a time when his younger brother was preparing to go to college. The burden of two college tuitions would have proved too much for his family, so, as Bourdain told Wealthsimple, he called his parents to explain that he would drop out of college.

Bourdain wrote himself out of the restaurant industry

"He was going to do well; I clearly was not. I was a waste of money and of an education," he explained. He then enrolled in the Culinary Institute of America to develop the skills further. By 1997, Bourdain had enough of his dysfunctional culinary existence. Explaining his dream to transition from cooking to writing, Bourdain shared in an interview with The New York Times the pitch for a book: "My dream book, a definitive, foody memoir, a ribald account of my 22 years in the restaurant business that would probably appall and horrify anyone thinking of hiring me.” That book was "Kitchen Confidential."

It charts his not very successful career as a chef bouncing from one failing restaurant to another to sustain his addictions until mellowing out at Les Halles. "We cooked and did whatever we wanted to do, which was smoking pot, drinking, rambling around New York hanging out with chefs and talking about life," John Tesar, whom Bourdain calls Jimmy Sears in his book, recounted for Eater Dallas.

The kitchen as pirate ship was a product of its time and Bourdain's own personality. Francis Lam remembers in Salon that when "Kitchen Confidential" came out while they were studying at the CIA, teachers fumed about "this guy Bourdain" who made the entire industry look like scumbags. Ironically, the desperado glamour the book brought to the industry also brought scrutiny to lapses in professionalism.

Bourdain wasn't always interested in television

Much of Bourdain's own career could now exist only as HR horror stories, much to his own approval. Talking to Smithsonian Magazine, Bourdain stated he thought too many people liked the book for the wrong reasons: It validated bad behavior.

"He used to always say, 'Don't let me do TV ... If I ever do TV, shoot me," Karen Rinaldi, one of Anthony Bourdain's long-term friends, remembered for "Roadrunner." Yet the work he is best remembered for is his series of television shows. According to Lydia Tenaglia and Chris Collins, co-founders of Zero Point Zero, the production house behind Bourdain, he remained ambivalent about hosting a television show even as they began filming "A Cook's Tour." Tenaglia had read "Kitchen Confidential" and heard Bourdain was considering a follow-up. She decided to ask if he wanted to meet and his reaction, as she detailed to The Ringer, was something along the lines of "Yeah, sure, whatever."

During the meeting, Tenaglia and Collins realized that Bourdain was only interested in their idea as far as it provided raw material for his next book. However, as the series progressed, Bourdain began to write more and more of the narration himself, transforming the experience into his own storytelling medium. "He was writing ideas and lines before we even got there," Collins remembered, "because he had a greater understanding of what he was gonna get." Bourdain understood that the show was a natural vehicle for his writing.

The shows are one continuous project

You can watch Bourdain stumble through Tokyo in the first episode of "A Cook's Tour," and then follow him along the streets of the Lower East Side for "Parts Unknown," and see the evolution of a single project with a single team.

This, as Caitlin Quinlan writes in Hyperallergic, is in part because all of his shows share a general Bourdain aesthetic: "Starting with the punchy opening title sequences set to guitar-heavy music which splatter images of the chef eating and exploring in rapid succession. All focus on sound as fundamental to the dining experience, paying attention to the chatter of patrons, the screech of cars on streets, the vibrancy of city centers."

The programs were more dictated by the production team, refusing to compromise with network executives, than any natural narrative close. Bon Appétit notes "A Cook's Tour" ended because the Food Network refused to fund Bourdain's meeting with Ferran Adria in Barcelona, stating that viewing numbers were better when he visited domestic barbecue. In the second episode of "No Reservations," Bourdain met Adria in Barcelona (via Travel Channel). Similarly, The Ringer writes that "No Reservations" ended when the Travel Channel wanted Bourdain to remain in America and to strip down what they filmed. Instead, the show jumped to CNN, which allowed Bourdain and his team to pursue whatever stories they wanted, in whatever manner they wanted.

An experience in Lebanon expanded his mission

If you wanted to pin a moment when Bourdain's shows jumped from being about Anthony Bourdain wandering around to find something to eat to the ambitious explorations for which many remember him, you have to look to the "No Reservations" episode on Beirut.

After 10 hours of filming various scenes, war between Hezbollah and Israel erupted with rocket attacks, airstrikes, and the bombing of Beirut's airport. The production crew managed to escape, but the experience marked Bourdain. Writing in The Atlantic, Kim Ghattas, a Lebanese reporter for the BBC, remembers how despite the drama surrounding him, Bourdain kept the story focused on Lebanon, and kept it from being terrifying: "I knew his episode had told my country's story better than I ever could."

"I came away from the experience deeply embittered, confused — and determined to make television differently than I had before," Bourdain later mused in a blog. "I just saw that there were realities beyond what was on my plate, and those realities almost inevitably informed what was — or was not — for dinner. To ignore them had come to seem monstrous."

Commercially, the episode cemented Bourdain's place in television. It earned the team their first Emmy nomination, though they didn't win (via IMDb). It also, as Pat Younge told The Ringer, was the first Bourdain episode to receive a .7 or .8 rating.

His addiction to his work ruined his relationships

The impulse behind Bourdain's various addictions attached him to the shows he produced, straining his relationships until they broke.

In a list of revelations in "Roadrunner," Vulture writes that the initial fame that Bourdain dived into broke his marriage of more than 20 years to Nancy Putkoski. Ottavia Busia, his second wife and mother of his only child, said Bourdain was on the road for 250 days a year, which proved too long to sustain their marriage. Asia Argento, his partner at the time of his death, raised the same point when she spoke with the Daily Mail about the people who considered her cheating as the cause for his death: "He was a man who traveled 265 days a year. When we saw each other, we took really great pleasure in each other's presence, but we are not children. We are grown-ups."

But why would a person who repeatedly found himself in a happy relationship advance his career at the expense of those in whose company he found pleasure? Talking to The Guardian in 2006, Bourdain recalled returning to the United States after visiting Vietnam: "I had seen that ... colour ... and I knew that that had changed me, altered the way I would look at things. And the first time I went back to America, I found I was right. Everything was flat. Everything." Bourdain lusted after the novelty he found in his first oyster.

He grew out of 'Kitchen Confidential'

Bourdain and Argento were dating when Ronan Farrow published the accusations of sexual assault made by Argento, Rose McGowan, and many others against Harvey Weinstein in The New Yorker. For Bourdain, the stories led to introspection. "Why was I not the sort of person, or why was I not seen as the sort of person, that these women could feel comfortable confiding in?" Bourdain rhetorically asked Isaac Choitner in an interview for Slate. "I see this as a personal failing."

The stories led him to reconsider his portrayal of the world in "Kitchen Confidential." Reflecting on the topic for Medium, he saw his book in an even bleaker light: "To the extent which my work in 'Kitchen Confidential' celebrated or prolonged a culture that allowed the kind of grotesque behaviors we're hearing about all too frequently is something I think about daily, with real remorse."

However, even without the drama of the Weinstein scandal, Bourdain had already moved beyond that persona. When Ariane, his daughter, was born, he realized that he had become a different man. "The earring's gone," he told Entertainment Weekly in 2010. "It ain't dignified ... I think it's just I don't see myself as the angry young man anymore."

Bourdain's hero gave him the advice he needed

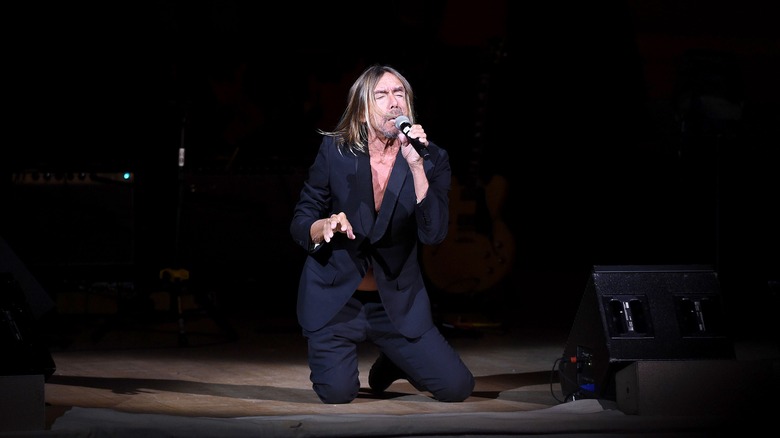

Talking to Grub Street, Neville notes that Bourdain's heroes Iggy Pop and Keith Richards managed to transcend the nonsense of the media, reaching a kind of zen state where they couldn't care less. Bourdain, Neville discovered, existed as a strong contrast to this. "But Tony would constantly say, 'I'm going back to my room to Google my name.'" An example explodes later in which he sees the pictures of Asia Argento and Hugo Clement kissing. His reaction was not so much a heartbroken lover, but that of a humiliated man who survived for decades on the machismo of the kitchen. "I want to be careful about how I say this," Neville said, "but for him to feel that he had staked himself so far out on the limb to be made to feel like a chump so publicly. That was the thing — not heartbreak. Humiliation."

For Neville, the most important moment in "Roadrunner" was when Bourdain met Iggy Pop. Bourdain asks Pop what thrills him, to which Pop replies, "Being loved and appreciating the people that give that to me."

"God," Neville exclaimed to Rolling Stone after describing that scene, "if that isn't what Tony needed to hear — I just don't think he was capable of hearing that."

Anthony Bourdain died on June 8, 2018

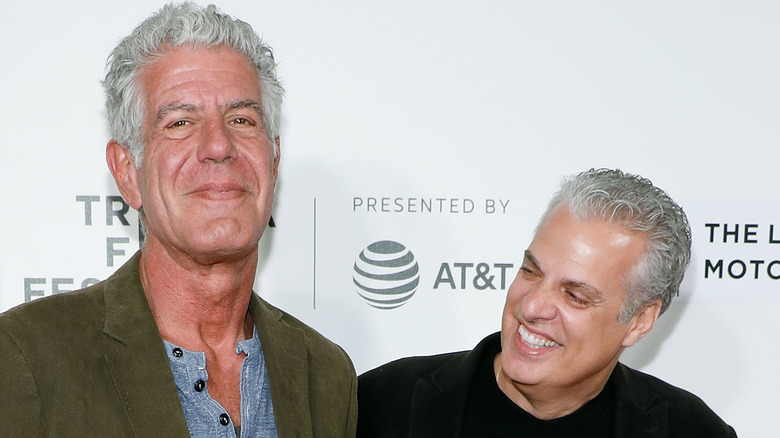

On the evening of June 8, 2018, Eric Ripert, a close friend and fellow chef, found Anthony Bourdain unresponsive in a room at the Le Chambard hotel in Kaysersberg, France. The BBC reported reactions from a range of people encompassing former president Barack Obama, astronaut Scott Kelly, and actress Rose McGowan, among many others.

"I know it was a very unpremeditated act," Neville told Rolling Stone. "He was giving notes on edits that afternoon. He was making lunch reservations with a friend for the next week." Neville also told the outlet that suicidal episodes, which Bourdain was subjected to for decades, tend around 90 minutes. What made this moment different, resulting in his death, has been left as an open question.

What is not in question, however, is the impact that the man who became Anthony Bourdain had made. He brought a holistic attention to food in a way not seen before, and as his career advanced he found the world to be ever more inexplicable. He could never stop moving forwards, but in doing so, he always discovered more and more of the world. The New York Times quoted him this way: "Life is complicated. It's filled with nuance. It's unsatisfying. If I believe in anything, it is doubt."

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).