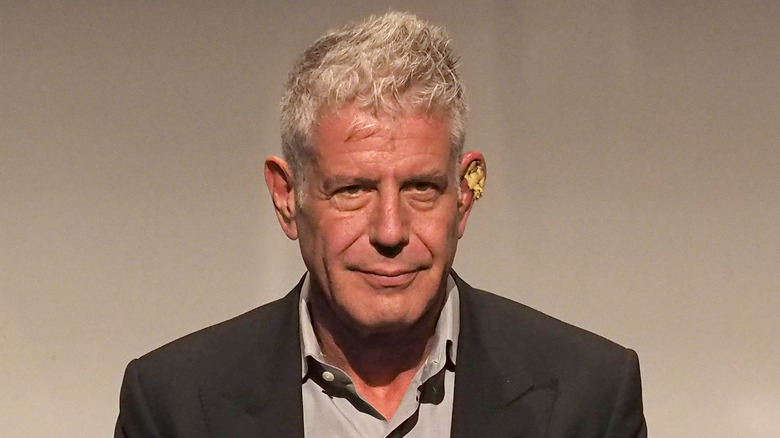

The Untold Truth Of Anthony Bourdain's Kitchen Confidential

When Anthony Bourdain's memoir "Kitchen Confidential" was released in 2000, it turned the food world on its ear. The memoir, Bourdain's snarky, sometimes obscenity-laden story of his rocky journey from flailing rich kid to professional chef, laid bare the unglamorous reality of life behind the doors of restaurant kitchens. "Kitchen Confidential" offered its scandalized (but fascinated) readers a graphic look at an intense, insular professional culture with brutal working hours, dangerous working conditions, (mostly) terrible pay, and a lot of truly strange people. In short, as The New York Times noted, it was a bracing antidote to much food writing of the time, which tended to paint a glossy, idealized image of chefs and their kitchens.

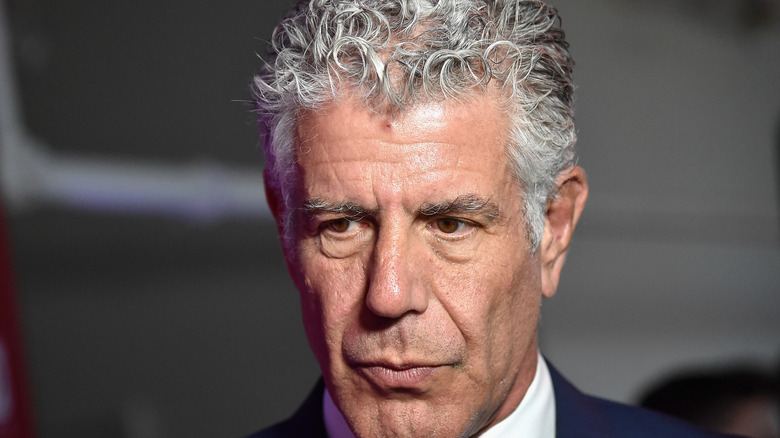

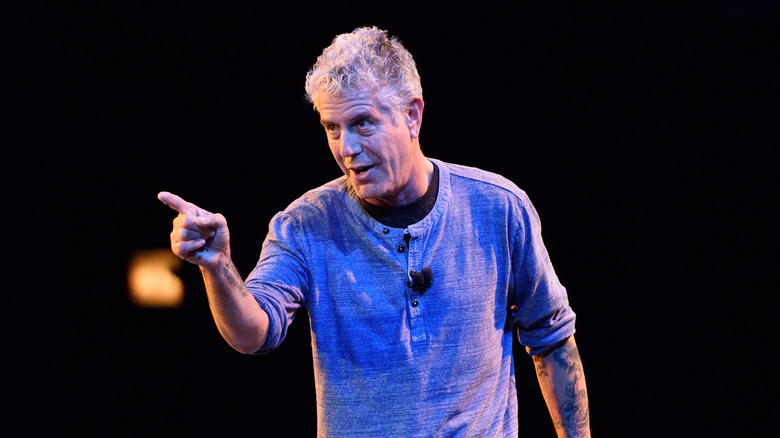

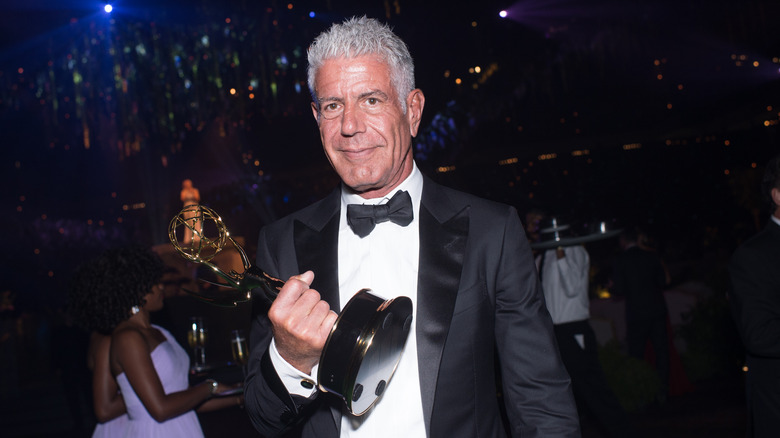

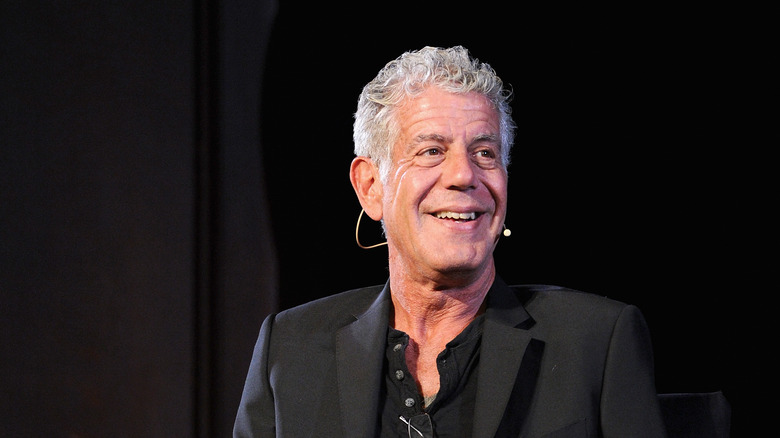

The popularity of "Kitchen Confidential" would radically change the course of Bourdain's life. Almost overnight, he went from working executive chef at what The Ringer called a "middle-brow steak-frites joint" to full-time culinary celebrity, hosting a number of food and travel-related shows including "Anthony Bourdain: No Reservations," "The Layover," and "Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown," as well as guest judging on "Top Chef" according to Britannica.

Unfortunately, while his passion for and curiosity about food endured throughout his busy career, so did his personal demons, and he took his life in 2018 in France while shooting "Parts Unknown." But "Kitchen Confidential" remains a culinary classic and has informed how a generation of food lovers view restaurants and cooking.

Kitchen Confidential began as a tell-all New Yorker article

The first exposure most foodies got to Anthony Bourdain was an eye-catching 1999 article in The New Yorker entitled "Don't Eat Before Reading This," which began with the memorable line "Good food, good eating, is all about blood and organs, cruelty and decay." And it only got more graphic from there: In the article, in which Bourdain identified himself as a working chef, he revealed the seamy underside of culinary culture — such as the strong possibility that the bread in your breadbasket had probably been served to another table before. (And yes, Bourdain wrote that he eats it anyway.)

The article generated a huge buzz (and may have moved some diners to give the breadbasket a pass when eating out). But even before it came out, Bourdain's friend Karen Rinaldi, a publisher and editor, had seen some of his informal written observations about cooking — such as his personal emails — and had been trying to convince him to write about his culinary adventures, according to The Kitchn. He happily agreed — and expanded upon his New Yorker essay, turning it into what would become "Kitchen Confidential." Like his original essay, the book was a huge hit. "We ran out of stock in the first week," Rinaldi said.

The book earned critical acclaim

The appeal of "Kitchen Confidential" wasn't limited to its shock factor. Critics were also wowed by Anthony Bourdain's writing. "I don't know about his cooking, but this guy can write," wrote Deirdre Donahue in USA Today. "This is the kind of book you read in one sitting, then rush about annoying your co-workers by declaiming whole passages," Donahue continued. The New York Times was even more effusive in its praise. "In a style partaking of Hunter S. Thompson, Iggy Pop and a little Jonathan Swift, Bourdain gleefully rips through the scenery to reveal private backstage horrors little dreamed of by the trusting public," wrote reviewer Thomas McNamee.

International critics likewise praised the book. While Jay Rayner, restaurant critic for The Guardian, found some of the New York-specific descriptions would be close to incomprehensible to British readers, he ultimately lauded the book for its clear-eyed wit and for Bourdain's obvious respect for food and the culinary profession. "There are very few books which all professional cooks should read but this is one," Rayner wrote. "To Escoffier and Larousse may now be added the name Bourdain."

Anthony Bourdain was already a published novelist before writing Kitchen Confidential

To most casual fans and foodies, Anthony Bourdain's literary success was a happy fluke — here was a guy who spent his days in front of a deep fryer and by dint of sheer luck and a compelling personal story found himself near the top of the New York Times bestseller list. In short, he's commonly thought of as an overnight literary success.

However, nothing could be further from the truth. In reality, neither his viral New Yorker article nor "Kitchen Confidential" were his first run-ins with editors and publishers. According to the New York Post, Bourdain's mother, Gladys Bourdain, was a copy editor at The New York Times and recognized his writing talent early. And a fellow chef, Scott Bryan, told the New York Post that "Tony saw himself as more of a writer than a chef."

Bourdain took his literary ambitions seriously, writing two published novels while working as a full-time chef before "Kitchen Confidential" was released, according to Eater. Even in his first novel, "Bone in the Throat," Bourdain's love of over-the-top storytelling, dark wit, and food was evident. As Publishers Weekly observed in its review of the novel, "The cast of this dark-humored, street-smart novel romps through Greenwich Village and Little Italy on a testosterone high in a perfect sendup of macho mobsters and feebs alike, while the kitchen antics reveal a real love for – and knowledge of – cooking."

He later regretted glamorizing the macho culture of restaurant kitchens

When "Kitchen Confidential" first came out, a big shock for many readers was the depraved, hyper-macho culture in restaurant kitchens. In the book, Anthony Bourdain described the "testosterone-driven, male-dominated world of restaurant kitchens" as unapologetically crude and sexualized, a place where few women can survive, let alone thrive, professionally. (He does add, though, that "To have a tough-as-nails, foul-mouthed, trash-talking line cook on your team can be a true joy — and a civilizing factor in a unit where conversation tends to center around who's got the bigger balls.")

But as Slate noted, Bourdain's gleeful embrace of this exaggerated machismo has not aged well. In light of the #MeToo movement and with two decades of hindsight, readers can see the world Bourdain celebrated for what it was -– an oppressive, pathologically sexist, and hurtful culture. And Bourdain himself became aware of this in his later years, in part because of his relationship with actress Asia Argento, who was among the many women to accuse Harvey Weinstein of sexual assault.

"That certainly brought it home in a personal way that, to my discredit, it might not have before," he told Slate. He also wondered aloud to Slate if "Kitchen Confidential" contributed to the perpetuation of this culture. "I've had to ask myself, and I have been for some time, 'To what extent in that book did I provide validation to meatheads?'"

Kitchen Confidential transformed Anthony Bourdain's life

While Anthony Bourdain had two published novels under his belt before writing "Kitchen Confidential," neither attracted a lot of attention, and according to The Kitchn, he'd grown frustrated with his fiction-writing career. But with the publication of "Kitchen Confidential," his life changed almost overnight. Not only did readers relish his over-the-top tales of kitchen misbehavior, his fellow cooks and chefs saw him as their hero and spokesman. "Since the book came out, I've never had so much free booze and free food in my life," he said on KCRW's radio show Good Food. "Chefs and cooks everywhere seem to see me as the poster boy for bad behavior in kitchens."

Not surprisingly, his transition from working chef to full-time celebrity had its awkward moments. "Honestly he wasn't that great in the media at first. Tony was shy and a little awkward at first — and lovely," his friend Karen Rinaldi told The Kitchn. "In the beginning it was kinda funny to see him on television — but he was incredibly smart, and he started nailing it very quickly," she said.

Kitchen Confidential offered restaurant dining secrets to readers

One of the many unusual charms of "Kitchen Confidential" is that Anthony Bourdain often addressed his readers directly, with everything from advice on launching your own culinary career (if you dare) to essential kitchen equipment for home cooks. But among the most talked-about tips he offered readers were his secrets to restaurant dining — what to order, what to avoid, and why.

Many of these tips relate to the typical schedules of restaurants and their purveyors. For instance, in "Kitchen Confidential," Bourdain advises against ordering fish on Mondays — because seafood purveyors typically make deliveries on Friday, any fish available the following Monday has been sitting around for a while. Similarly, he recommends Tuesdays as the best nights for fine dining — your food will be fresh, since restaurants get fresh supplies on Tuesdays, and because chefs typically get Sundays and/or Mondays off, Tuesday diners also benefit from a refreshed, focused crew in the kitchen.

Bourdain hated the Food Network — and Kitchen Confidential was his protest

While TV was a huge part of Anthony Bourdain's later career and he both hosted and made guest appearances on numerous shows, according to Britannica, he had little patience for celebrity chef culture and the superficial, glamorized view of cooking propagated by chefs such as Emeril Lagasse and TV personalities such as Rachael Ray, according to The Ringer. And, per The Ringer, he absolutely loathed everything the Food Network and its stars stood for — including the way it both glamorized and trivialized food. "I don't dislike Guy Fieri," he wrote in a later book, "Medium Raw" (per Grubstreet), "I just dislike — really dislike — the idea that somebody would put Texas-style barbecue inside a f*ing nori roll."

In "Kitchen Confidential," Bourdain showed not only profound respect for and curiosity about food ("Food had power. It could inspire, astonish, shock, excite, delight, and impress," he wrote), but that unlike cooking on TV, professional cooking in real life is hard and unglamorous work. In real-life kitchens, he wrote, consistency and technical discipline matter much more than a flashy personality, creativity, or personal fulfillment. "The job requires character — and endurance. A good line cook never shows up late, never calls in sick, and works through pain and injury," he wrote.

Bourdain's travels following Kitchen Confidential opened his eyes — and destroyed his two marriages

The success of "Kitchen Confidential" gave Anthony Bourdain the opportunity to expand his horizons — literally. With his move to television and shows such as "No Reservations" and "Parts Unknown," he built a reputation as a globe-trotting cultural anthropologist who explored the world's varied cultures and traditions through the lens of food and culinary traditions, according to The Ringer. Viewers loved traveling the world vicariously with him as he watched cooks prepare their traditional specialties and share their stories.

But while all Bourdain's travel and exploration were great fun for him and his viewers, they proved to be less than fun for those he left behind. His high-school sweetheart and first wife, Nancy Putkowski, gladly endured his years of long hours and bad behavior as a chef, but his constant travels proved to be a deal-breaker for her and resulted in the end of their 20-year marriage, according to Heavy. His second marriage, to fellow restaurant veteran Ottavia Busia, suffered a similar fate — the couple separated (but never formally divorced) after six years, their relationship also irreparably strained by Bourdain's frequent absences.

In Kitchen Confidential, Bourdain shared his struggles with addiction and depression

In "Kitchen Confidential," Anthony Bourdain was brutally honest about his own flaws and personal struggles. He described his college-age self as a "spoiled, miserable, narcissistic, self-destructive, and thoughtless young lout." And life did indeed kick his butt many times over the years. Some of his heartaches came from the stress and pressure of professional cooking, but all too often, it was caused by his own personal struggles with both depression and drug and alcohol addiction. Even worse, none of these stressors occurred in isolation — his depression and emotional instability, attempts to self-medicate (or resist self-medicating) with drugs and alcohol, and work demands made for a toxic combination. "It is one of the central ironies of my career that as soon as I got off heroin, things started getting really bad," he wrote in "Kitchen Confidential" (per Slate). "Stabilized on methadone, I became nearly unemployable by polite society: a shiftless, untrustworthy coke-sniffer, sneak thief and corner-cutting hack."

The fact that Bourdain found his calling and passion in the restaurant industry didn't help. According to FSR Magazine, restaurant workers have the highest rate of alcohol abuse and the third-highest rates of drug use of all professions. Late working hours and easy access to alcohol, combined with low pay, high stress, and job insecurity, make the temptation to self-medicate too great to avoid for many culinary workers — Bourdain among them.

Bourdain considered himself a good — but not great — chef

"Kitchen Confidential" revealed Anthony Bourdain to be a tough critic of his fellow chefs, and in his career following "Kitchen Confidential," he didn't hesitate to take down high-profile figures he believed to be overrated. He blasted Rachael Ray, for instance, for promoting "the smug reassurance that mediocrity is enough" and in "Kitchen Confidential," he even dissed his fellow Culinary Institute of America alumni as "clumsy, sniveling little punks" who were "possessed of egos requiring constant stroking and tune-ups."

But he was also an honest-enough critic to recognize that while he was competent, he wasn't among the culinary elite himself. He shared in "Kitchen Confidential" how he was ecstatic to land an executive chef position at an elite restaurant — and immediately found himself way in over his head.

"I was, I'm telling you for the record, unqualified for the job," he wrote. One reason he was unqualified, he later shared, was that his early career choices were more often driven by money than by intentional professional development. Unlike many ambitious aspiring chefs, he opted to take better-paying chef positions at less-reputable restaurants rather than lower-paying apprenticeships with master chefs, where he could have mastered the fine points of cooking technique and kitchen management. "Used to a certain quality of life — as divorcees, like to call it, living in the style to which I'd grown accustomed — I was unwilling to take a step back and maybe learn a thing or two," he confessed.

In both his kitchens and his shows, Bourdain embraced people of different cultures

In his later career, Anthony Bourdain gained a reputation as not only a food lover, but as a cultural explorer who used food as a window into learning about other cultures. But his interest in cultural exploration wasn't new to him. Instead, it was fundamental part of his professional toolkit: As he shared in "Kitchen Confidential," kitchen crews tend to be largely composed of Spanish-speaking immigrants, and to lead them effectively, a chef needs to understand their backgrounds and cultures. "It's important that the crew knows that I care about them and will take care of them," Bourdain told the Harvard Business Review. "I take pleasure in personal details. I take pleasure in their lives. And I protect them."

And to do this effectively, Bourdain wrote in "Kitchen Confidential," chefs need to do their homework. "Should you become a leader, Spanish is absolutely essential," he wrote. "Also, learn as much as you can about the distinct cultures, histories, and geographies of Mexico, El Salvador, Ecuador, and the Dominican Republic." And even then, long before his television career, Bourdain described food as a means of intercultural education. "Learn their language. Eat their food. It will be personally rewarding and professionally invaluable."