Chef David Burke Reveals Answers To All Of Our Best Foodie Questions - Exclusive Interview

Chef David Burke is a one-of-a-kind, multi-award-winning culinary genius, whose creativity and talent are matched only by his astounding entrepreneurial skills. If you haven't seen much of him on television lately, it's only because he's been so busy running his many restaurants around the world (including six he opened during the pandemic), coming up with new programming involving his three-foot-tall puppet sous chef, Lefto, and formulating plans for a very unique sort of culinary school.

David Burke began his career in the early 1980s, training under Daniel Boulud and Charlie Palmer, among others, before rising from sous chef to executive chef at New York City's iconic River Café. He was just 26 at the time. The self-confessed "culinary prankster," low-key French pastry prodigy, and inventor of the patented Himalayan salt method for dry-aging steak, was crushing prestigious cooking competitions a decade before "Iron Chef" or "Top Chef" even existed. Of course, Burke has done those too. In fact, even as dining-in is starting up again, Burke is invigorated by visions of a rematch with longtime friend slash nemesis, Bobby Flay. But first, Burke headed to the Hamptons to help raise funds for the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation, which he's been involved with for many years and has special meaning to him because of his father's recent cancer diagnosis. This year, Burke was named as an honoree at the 17th Annual Hamptons Happening benefit for the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation.

In the midst of all that, Burke somehow managed to squeeze in an exclusive interview with Mashed, in which he told us, basically, everything and then some.

That time when Chef David Burke pranked Chefs Joe Bastianich and Thomas Keller

You're known as the "culinary prankster." Can you talk about what that means?

It's the element of surprise and making people laugh. It keeps it interesting. At the end of the day, we're nurturing people. The word "hospitality" comes from "hospital" – it's nurturing, and no matter how you do it, it's hard work, so you've got to have a little fun.

What are some of the best culinary pranks that you've done?

Some of the pranks we've done on other employees have been quite fun, although not always politically correct. But pranking can be in the way you serve a dish. For example, the lollypop tree we made for our cheesecake, or putting bacon on a clothesline, serving it with clothespins. Or, the time I cooked for Thomas Keller and Joe [Bastianich] in Napa, and I made a watercress and escargot soup. We had local snails, live in the shells. We boiled some, but I also kept some alive. So I put the soup in a bowl — hot, really green, watercress, snail, garlic soup, and I took the live snails and slapped them right on the rim of the plate and they stuck to the rim and their heads shot out because it was hot, and I was like, "That's your escargot soup." We didn't torture the snail, but we surprised everybody.

That reminds me of the time on Top Chef when you had the competitors to your Townhouse restaurant, and there was a dish involving live goldfish.

I think we gave them goldfish to use in presenting a dish on top of the bowl. Say you had a glass bowl and you put water in it with the fish, maybe some seaweed, and then you'd put a salad on top of that on a plate, so that became part of the theme of the dish or the uniqueness of how we served it. Now, we used to do little baby crabs the size of a snail — used to get them from Korea live. We would put these live crabs underneath warm peppercorns and we would put hot oysters on top of the peppercorns, but as you were eating them, they would crawl to the top. They would start coming out of the "sand" — really the salt and pepper — and all of a sudden you'd see a little baby claw come out. To me, I just think that adds something to the conversation and the "Wow, look at this s***, something's moving."

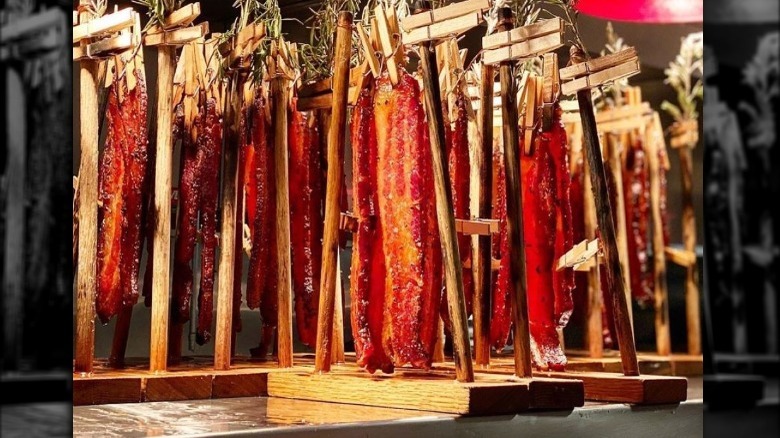

We also did crickets on a pizza, we did crickets frozen into ice cubes, and we served lobster on a bed of nails — like a florist would use. And sometimes it really makes sense to hang bacon from a clothesline. It's just that nobody's ever done it. Why wouldn't you hang bacon and render the fat down, use the clothespins as a chopstick. So that became an instant hit.

Chef David Burke reveals the one and only story behind his iconic Clothesline Bacon

How did the bacon clothesline happen?

The bacon's on all of our menus. It's been around a while — at least 15 years — don't let anyone try to fool you, telling you they did it first. We were doing a charity event in Vegas and we made fruit leather with berries and mango and another one with ketchup, so we had three different colored leathers and they were in big sheet pan sized, rectangular strips. So we were doing the foie gras and duck with the fruit leather, and the leather was going to be like the little wrapper — like a taco. But we couldn't get it to dry quick enough, so I yelled at everybody, of course, and told them to hang it at the event and we'll get a fan to blow on it. I said, "Go buy some of those laundry racks that you put towels on, the wooden folding ones." So we bought three or four of those, put the fruit paper on it, put the fan behind it and we hung a couple of ducks on the racks too.

We were the hit of the party. We were using scissors, we had to cut the fruit leather with scissors, and then we started cutting the duck legs with the scissors and making these wraps, and people were like, "What a genius idea." The clothespins came with those things, so we had clothespins that came with the racks, so the clothespins were laying around, and we started closing the taco with the fruit leather with the clothespin and blow-drying them with the fans. The duck fat was falling down, so I was like, "If we hung bacon, we'd have a home run." That's how it was born, by a mistake.

Is it frustrating when people copy you without attribution?

When I was younger, I'd always get a little upset if someone took credit for a dish I created, and it happened a lot, but now it's like you put it out there and it's like writing a song. You try to get credit, but it's hard to trademark food. I learned this when I worked for Singapore Airlines — some of the best chefs in the world were consultants, and we used to have these ideation sessions. I raised my hand and said, "Don't you get tired of being copied by all the other airlines? Every time we come up with something top level, a year later Lufthansa's doing it." They said, "As long as they're copying us, they'll never be us." The fact is they're never going to out-think you, because they're waiting for you to make the first chess move. You'll always be ahead of the innovation, if you're innovative enough.

Chef David Burke explains what it was like being one of NYC's youngest top chefs

What was it like being one of the youngest chefs on the burgeoning New York City restaurant scene?

I got to New York in '84 and worked for Daniel Boulud, then for Charlie Palmer as sous chef at the River Café. I had been working with a really talented couple of chefs before that, and I was a really good cook, and I had worked in Europe already. But New York was a boiling little pot — simmering to get respect for American food. You had French restaurants all over the Upper East Side and of the top 20 restaurants, 12 of them were French. So after two years at River Café, I went to France for two or three months and worked for various really great restaurants before coming back as executive chef.

Before going back, I told Buzzy [O'Keeffe -- the owner of the River Café], "I don't know if I can handle this job." I was just 25 or 26. He goes, "You're doing the job now and the whole staff thinks you can do it," which was a real vote of confidence because I thought the waiters hated me. I was very demanding on them, I wanted perfection, but they respected me. And then Buzzy and I made a deal to send me to pastry school in Paris and then come back as chef.

Were you the youngest chef at a top restaurant?

I had to be. Listen, I'm still on the young side compared to all the guys I came up with ... Daniel Boulud, Jean-Georges Vongerichten, all the guys you read about. Eric Ripert's on the younger side, and we were probably around the same age. But at 26, to be running a three-star restaurant was impossible. More important, I was following Larry Forgione and Charlie Palmer. That was a big task, and I was nervous. I knew how to cook, but I didn't know how to run a business yet and run a kitchen, but I guess I was doing it without realizing you're actually doing it. I wasn't doing the ordering as much, and I wasn't doing the payroll, but Buzzy flanked me with the right people to do it. He said, "I just want you to create and cook." So I did.

So, the adrenaline factor...

Hundred percent. Being nervous to me creates great energy. Because I love the challenge and I don't like failing, so it's like I got up nervous every day and went to work and turned that nervous energy into productivity and creativity. I could do whatever I wanted, and my imagination, my creativity was boundless. Let's do this, let's do this. I built a beautiful team of people and we knocked it out. We represented the United States that first year in the Culinary Olympics in Tokyo. I was 26, and we won two gold medals, it was fantastic.

Chef David Burke on how he became the only American ever to win the "MOF"

So, is it true you were the first American ever to win the coveted "Meilleur Ouvrier de France" ("Best Craftsman of France," aka the MOF)?

The only American to win. I'm probably the only American that ever will. They caught so much flack for that. I think they assumed the French chef was going to win because he was in line for it. But we did such a good job, it would have been obvious it was biased if we didn't win. It wasn't only the French judging, every country had a judge. So with every country judging, we cleaned the clock. It's a great feeling... American food wasn't that respected. It was 1988, and I think they assumed I'm going to make steak and potatoes or something.

What did you make?

The competition was 10 days, so we made a variety of different things. One of our dishes that represented America was quail that had the flavors of apple pie. We smoked the quail with cinnamon, made a pecan soup, a pecan consommé, and made apple raviolis with dumplings, and a poached quail egg, it was gorgeous. I explained, "These are all the flavors of apple pie, but with an American bird and the smokiness."

We also made a Maine lobster with oysters from Maine and the tribute to the East Coast with black olive noodles to represent New York City and the Boston Italian, and Little Italy. For the dessert, we did a chocolate bourbon torte. We built a log cabin out of chocolate with a maple cookie. The log cabin represented Abe Lincoln, and it had a butterfly of chocolate, which represented freedom. That was like the clinch.

Are you able to create dishes like that in your restaurants?

My whole menu is designed around stuff like that. When we design dishes, especially pastry, we try to have a theme to it, a reason. Not just, "Hey, let's make a chocolate malted cake with vanilla ice cream." That's not good enough for me. I want to tell a story, we're writing a song. This is a dish, this is not an afterthought, this is a thought. Think about it, Charlie Palmer, great chef, right? He opens Aureole, on Park and 61st Street, I open Park Avenue Café several years later two blocks away. How is my crème brûlée going to be better than his when we both have the same recipe? I had to out-maneuver him, out-style him. So I made my crème brûlée with chocolate and in a glass sugared candy dish that had a lid on it, and inside that lid I put a chocolate butterfly. So when you lifted the lid at the table, you got a surprise. No other crème brulee in America had a lid on it. It took me a lot, so I had to get up earlier, stay out later, which I was very good at.

Chef David Burke hereby challenges Bobby Flay to a rematch

I remember hearing that the all the top NYC chefs back in the day would hang out at some restaurant or other after hours?

You had Blue Ribbon, and a couple of other chef hangouts. We'd work until 11 or 12 and then go there and eat dinner. In New York, you could serve until three, four in the morning. We'd all gather and shoot the s***. It was a fun time, because it was all new to us, and that's how we communicated. There was no Instagram then. We'd compare dishes and eat some oysters, drink some wine and swap stories.

What's it like competing against these other chefs — like Bobby Flay — who were part of that scene?

It's like playing one on one basketball with them. It's very respectful. But we're still very competitive at the end of the day. I competed with Jean-Louis Palladin in the early days of the Food Network, and he got upset when I beat him. He got visibly upset. I went to pastry school, so I made deserts that were so good, and I beat him on that. I loved the guy, but I'm playing to win, man, I'm playing to win. Jean-Louis Palladin — I beat him, and he wouldn't share a cab with me. It was twisted, he was throwing things on the ground, but he was mad at himself, not me. I'm like, "Hey, have a nice day, take it easy." But he liked me a lot, and he was an older French guy, not that much older, but he was hot s***.

Now Bobby, I always admired Bobby because he was very humble at the beginning, and he also gave credit when credit was due. He had respect for me and I liked that he came out swinging. He wasn't at the French level of food, but he pioneered the Southwestern stuff, and he works hard. I think he's very good on TV, he's had some success in the restaurants, he's a well-known person, he's certainly successful, he's always been nice to me. When I was on Iron Chef with Bobby, I didn't see everything he made, but I honestly I thought he did a better job.

Would you consider a rematch?

Hundred percent. I would love it. Put it in the article, and demand an answer by sundown. Bobby'll get a kick out of it, it will be fun. He comes up to Saratoga in the summer, I usually see him up there, he comes to our restaurant. What's fun about a guy like Bobby or any of the other girls or guys that have been in the city since the '80s is you shared a lot of stuff together. Your paths are cemented, you're talking about four decades in the same city cooking together. You've seen a lot, all the comings and goings. So the people still standing deserve credit. It's a brutal business.

Chef David Burke on the pandemic and the related labor shortage

What was your experience like as a restaurateur during the pandemic?

We opened six places during the pandemic. When we got closed down, we were like, "Okay," my team and I, "what are we going to do?" We already planned to open to restaurants — Charlotte, East Brunsick, Saudi Arabia. So we're like, "Let's just move forward." So we continued to build. We opened in Charlotte, and for nine, 10 months, we didn't make a dime, we didn't pay rent, we lost money. But we built a beautiful place. We did a popup in Asbury Park, we built a beautiful restaurant with our partners in East Brunswick that opened in December, and we opened Belmar on the beach and a brewery, Red Horse we opened three months ago. We opened two restaurants, we opened one restaurant in Saudi Arabia, we're opening our next one in two weeks.

Is the restaurant labor shortage a factor?

Well, we're open, but we're struggling to get the right amount of staff and the right people in the right positions. But because we have a little bit of a corporate structure, we're all working. Listen, the people that are working in the restaurant industry now are killing themselves while other people can sit home and collect, and it's really not fair. So the ones that are working deserve a lot of credit, because they could sit home too. They could easily quit their job and collect unemployment, you don't have to get fired. You can just say, "I don't feel like working." It's a very strange thing that's going on, hopefully it's over in a few weeks. Because now, even though I'm busy, I've got to pay 25% more in payroll — it cuts into my profits, after not making money for a year and a half. New York City, we got devastated, we got our butt kicked, and I don't think it's going to come back, nor is the desire to be there as great as it once was for a guy in my position. Or for up and coming chefs. I don't think as much.

Any ideas about how to solve the labor shortage?

Well, you could stop paying people extra money to stay home. That would be the first start. I honestly didn't know they were still doing that, I thought that ended sometime in 2020 and the came back for a brief moment... It's crazy.

Chef David Burke sees nothing wrong with enjoying ketchup with steak ... or anything else, for that matter

I know you've said that Donald Trump did not put ketchup on the steak he ordered at your D.C. restaurant, BLT Prime, but what would be so wrong with ketchup on steak?

Nothing. Ketchup is a wonderful condiment, it's the most popular condiment in the world. Here's the idea of ketchup: Ketchup was designed for a couple of reasons, the number one reason is for digestion. That's why you put it on things that are fatty, like French fries, same as barbecue sauce, same as vinaigrette. All of these condiments are digestive aids, they help you digest fatty foods. It's got cloves and poultry seasoning in it and tomatoes and vinegar and sugar, and molasses. It also adds lots of flavor. My father likes steak with ketchup. If you eat hamburgers with ketchup, why can't you eat steak with ketchup? If your mother was the one that makes ketchup on top of your meatloaf, why can't you eat ketchup with steak? By the way, A1 Sauce and Worcestershire is not that much different than ketchup.

Is there anything you shouldn't have ketchup on? Like eggs or chicken?

I think you should put ketchup on everything, if you like ketchup. Life is too short, man. Life's too short to be having rules about ketchup. And if you want to talk about well-done steak and how people think it's sacrilege, that's another f***ing miss.

Yes, please talk about well-done steak.

Here's the well-done thing, because I got asked by a food critic, "Isn't it disgusting that Donald Trump eats his steak well-done?" I said, "Well, let me explain a couple things to

you. My father eats well done steak and my father's a good man. I would never tell my father that he doesn't know what he's doing when it comes to food, because he put

food on my table for years." But let me tell you something, a good steak — well-done — is still juicy and moist, because it has enough fat content. Look at short ribs, they're well-done. Pot roast, well-done. So a good marbled steak well-done is still a good steak. Now, I've judged many competitions, and the more you cook a steak, the better it tastes. Period. You can't argue with that because the caramelization that occurs creates a Maillard reaction. You know what tastes good on the outside of a roast turkey or ham? The skin, you know why? It's caramelized. Do you know why a hamburger's not boiled and it's grilled? Because it tastes better, you know why onion rings taste better fried? Because they're browned, when you caramelize things they get tastier. That's why English food sucks — because it was boiled. You didn't get any caramelization.

Chef David Burke talks turkey about his famous roast chicken recipe

You mentioned roast turkey, so now I'm reminded of a very well-known roast chicken recipe of yours from the '90s. Everyone was talking about it.

I had a couple — an onion crusted chicken, and a pretzel crusted one. The chicken we do now, the roasted chicken, it's a half roasted chicken. We brine it with seaweed (for umami) and sugar, so the brine helps crisp up the skin. It's fantastic. We used to put a roast garlic puree on it and then dry onion crumbs, and the skin was crispy, I think it's really good.

Why do you think roast chicken became such a thing in the '90s?

The '80s were all about fancy, big wine lists, expensive restaurants, prefixed restaurants. The economy drives the style in which we eat and also how we dress, what we drive and how you travel, et cetera, because that's where the money is, so you follow the trend. In the '90s, everyone started doing cafés and bistros. I went from the River Café to Park Avenue Café, still expensive, but it had that casual feel. We got rid of suit and ties of the '80s. And then what's a bistro? Roast chicken, a great roast chicken, and also it helps your cost. So chefs started getting creative with roast chicken, salad, and more comfort food came into play in the early '90s when we were in a recession.

What's your favorite thing to cook?

Roast chicken's one of them. Anything roasted. I liked to cook at home during the pandemic. Things you can put in the middle of a table like a holiday thing — like a whole roast, like a 10-pound lobster or a six-pound fish, or a big turkey, or a suckling pig. Chefs like to cook stuff like that. Because in a restaurant, we're always cooking in "onesie" portions — four scallops, two shrimp, we cook for one person at a time. So to do a roast and time it right and the whole aroma and the sizzle and the smell of something that you can put in the center of a table, enjoy it with friends and family, that's cool, because you don't do that in restaurants.

Chef David Burke on being a full-fledged American inventor

How did you come up with the Himalayan salt method of dry-aging beef?

People send me things because they know I'm creative, so the salt people sent me salt. It was sitting on my desk for like a year. I'd invented something called Flavor Sprays — fat-free, calorie-free, carb-free, diabetic-friendly flavored waters in little mist bottles. We had 35 flavors, bacon, blue cheese, Parmesan, birthday cake, strawberry, maple, all these flavors. They were selling like hotcakes. So I said, "You know what? If I can get dry aged beef flavor, all that umami into a bottle, I don't have to age all my steaks and my filet mignon could taste better."

So I gave this food scientist a piece of dry aged meat from my cooler at Park Avenue Café, and they analyzed it and came back to me, saying, "This is the most complicated thing for us to analyze from a flavor profile. You've got fat, you've got bone, you've got flesh, you've got decay, you've got mold, you've got umami, you've got blood, but the most interesting thing is that the number one flavor profile in your dry aged steak is cardboard."

I was like, "What?" He said, "Yeah, cardboard. It's interesting, right?" I said, "I'll be goddamned." He goes, "Do you leave the meat in the cardboard box?" I said, "No," but I went back to my refrigerator and noticed cardboard boxes on the floor, so I said to myself, if that cardboard could be absorbed by the meat, why wouldn't salt?" So if I replaced the cardboard with a whole wall of salt, now the salt air will go inside the steak. We were working on one invention to be able to create dry aged flavor in liquid form, and we came up with an aging process.

How'd they like it on Iron Chef?

On Iron Chef, I did a lamb carpaccio on the salt. One of the judges, she's like, "Oh, my god. David, I don't like lamb, and then you give me raw lamb." I said, "Well, if you don't like lamb, why are you judging?" Nah, I didn't say anything. But I put the salt on TV and just wanted to show off. Our theme was lamb, but I had a dish called Angry Lobster that was so beautiful — served on a bed of nails. So I made Angry Lobster and put it with lamb fritters, because I thought, "Let me show this dish to America, I don't care if I win or lose. I want to show them what we can do, because at the end of the day, nobody cares if you win or lose on the show, it's who put out the best product."

Chef David Burke gives us his two-minute egg sandwich recipe

What's your favorite food?

I love good Chinese food, I like everything. No, I have my comfort food, Italian hero, when I'm really down and out that's what I eat, when I'm exhausted. To eat out to dinner, I like everything. But I love good pasta, but I also love good Asian food. If I'm going to go out to dinner, I won't go out to a steakhouse to eat, I usually don't. I don't know, I like to learn when I eat, you know what I mean? So I try to go to a place where I could learn something. I love Peking duck done well, I like dumplings, I like everything. If I could eat a different meal every day for the rest of my life, it'd be great. But if I had to have only one item, it would be eggs.

Can you talk a little bit about that?

Well, eggs, we use them in so many things — pastry, appetizers, you can make bread with them, breakfast, brunch, binding eggs in dumplings, pasta, all that. It's a good source of protein, you throw it in stir fry, you can throw it in salads. It's just a versatile thing that a lot of people take for granted, the egg. Mayonnaise.

What's your favorite way of preparing eggs?

I like soft fried eggs, but I have something that I used to call the Chef's Express Breakfast, it was a two-minute breakfast. So here's how it goes, I cooked for my kids, I crack two eggs in a coffee cup with a little bit of butter, salt and pepper, a little bit of water, I scramble them, I put them in the microwave on two minutes. I drop two pieces of toast down and I make coffee. The coffee takes three minutes, the eggs are two minutes, and the toast is about two minutes, so in three minutes I've got the Chef's Breakfast. All I've got to do is clean two coffee cups.

The truth about Chef David Burke's "career" as a puppeteer

Did you always know you wanted to be a chef?

I was with some high school friends, and they were like, "You wanted to be a chef when you were a sophomore in high school. How did you know?" I'm like, "I didn't know anything about where it would take me." I just knew that there was something in it that made me happy to produce and cook and create and be part of a team, and be able to see a finished product on a daily basis. You don't have to wait a year to see the project done, you make something and you're part of a team. I think that was part of it. I also think there's a hospitality gene in certain people. You understand you're doing something good.

Was your family supportive?

When I got in the restaurant business, it was a bad choice of career. Everybody told me that. It was in the late '70s and you didn't get into it because it was respected, you didn't get into for the money, you didn't get into it for the fame. Being a chef was nothing back then. My dad says to me, "David, what is this talk about you want to be a chef or cook or whatever?"

I said, "Yeah, dad." I'm a smart kid, I'm a good athlete, I'm a pretty good boy in school, a little bit of a rascal, a little bit of a prankster.

My dad goes, "David, I know you smoke pot. I just didn't realize how much. Why the hell would you want to be a chef? Are you stoned?"

It was like telling your father, "I want to be a maid. I want to be a janitor." Being a cook was not looked upon as a profession. It was something you did without an education. First of all, you didn't need a license for it, you still don't, which baffles me. Here's a profession, you could poison somebody, and you don't need a license. But in order to fix their toilet, you do.

I understand you're also a puppeteer?

Amateur puppeteer, yes. I'm proud of that.

Can you talk about your puppet assistant, Lefto?

Entertaining people with Lefto, that was fun actually.

Any plans for Lefto going forward?

Yeah, Lefto, he's been dating a little lately, so I gave him a break. He's got a girlfriend — a female puppet, her name is Nutmeg — she's a mixologist, so she's going to teach drinks, and I'm going to teach, through Lefto, how to cook for a woman you meet on a dating site, like how to cook your first date meal.

Seriously? I'd watch.

It's educational, it's humorous, and it gives you tips on dating and cooking and drinks.

Chef David Burke muses on hotdogs and the difference between a cook and a chef

So just a few quick questions left here. First, where do you stand on whether a hot dog is a sandwich?

I don't think a hot dog is a sandwich. I don't think a hamburger is a sandwich, I think they're their own entity. I think sandwiches are cold, I don't think sandwiches are hot. A meatball hero is a hero, it's not a sandwich.

What do you see as the difference between a cook and a chef?

Well, a cook knows how to cook, and a chef knows how to run a kitchen and create. A cook can know one station, but there's many stations in a kitchen. We're working on opening up a culinary school in New Jersey, and we're working on something called "Culinary Religion." Not a cult, just a belief in hospitality and what it means to be a chef and being hospitable, and also layering in not wasting food, being kind, sharing food, doing charity work, community service, local farming, sustainability, all that. Then we're going to just build a clothing company for Culinary Religion with a great logo and fun little quotes that will be like, "Hug your farmer. Thank your fisher." Things like that, one-liners.

I want to make that something that's like what it means to me and some of my colleagues, and we're going to get some advisory boards, and we're just going to lay out a list of what we think. Basics, back to basic fundamentals of why we're in this business and our obligation to the public and our workers. We have an obligation to teach them how to do things correctly and mentor them so they can get in a better position.

Will Lefto be involved??

Lefto has got a following. Lefto gets away with things I can't say. Lefto could call out Bobby Flay and I can't. Lefto could say, "I think Bobby Flay cheated." And I can't.

If Lefto were to meet Bobby Flay on the street, what would he say to him?

He would say, "#ChewDoing, Bobby? Chewdoing?"

Learn more about the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation by visiting their website. Stay up to date with Chef David Burke's activities by visiting his website and social media.