The Untold Truth Of Farmer Brothers Coffee

Any business that has been around for more than a century must be doing something right. Some brands endure because of a unique appeal that extends down the generations. Coke, to give one example, has been based on the same formula since 1886 (except, of course, for a couple disastrous months of New Coke in 1985). Farmer Brothers Co. has a long history, too, but it's no Coca-Cola.

Farmer Brothers, established in California in 1912, packages and ships coffee, tea, spices, and related equipment across the U.S. According to the company's new hometown newspaper, The Dallas Morning News, Farmer Brothers roasts and sells nearly 100 million pounds of coffee a year. Starbucks goes through more than 500 million pounds a year (via Fast Company). At about one-fifth that size, Farmer Brothers is still pretty big. Even so, unlike Starbucks, nobody asks for Farmer Brothers by name.

That doesn't mean you haven't had a cup of the company's coffee somewhere in your travels. It might have been at a fine-dining or fast-food restaurant. Maybe you grabbed a cup at a hospital or retirement home. They serve Farmer Brothers in hotels, casinos, convenience stores, and campus dining halls, according to the brand's site.

Hotels, restaurants, and casinos in particular were hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, Farmer Brothers' business has suffered tremendously in the past year. But before we tell that story, we need to tell the rest of the story: How one man's bright idea launched a coffee empire almost nobody has heard of.

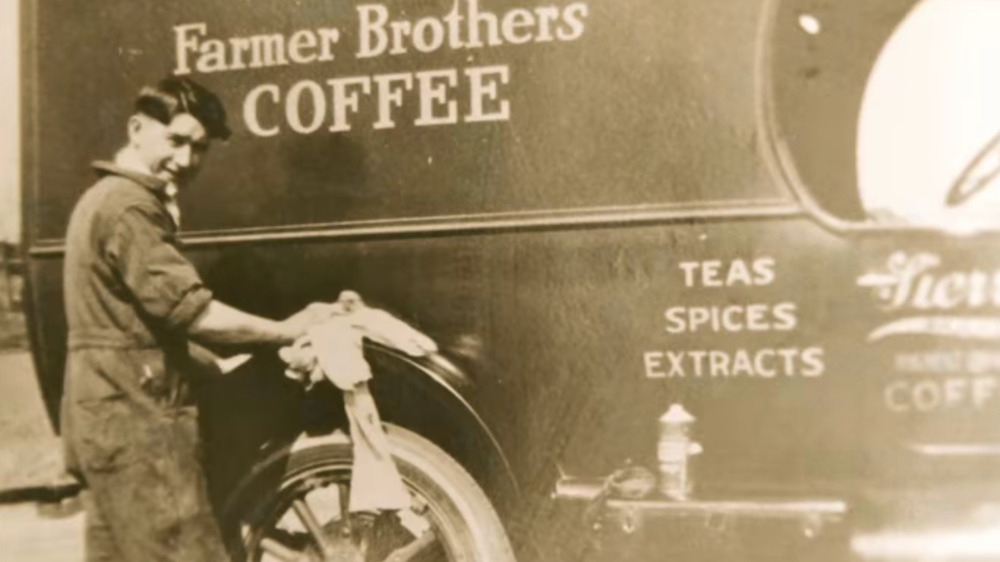

Farmer Brothers coffee started in the back of a bicycle shop

You'll find a five-minute slice of Farmer Brothers' century-long history on YouTube. In 1912, Roy E. Farmer had an idea: The coffee in Los Angeles restaurants wasn't that good, in his opinion, and he wanted to fix that. His coffee business started small, in the back of his brother's bicycle shop. Within three years, the brothers had made enough money to invest in a new coffee roaster and some delivery vehicles — some of them horse-drawn.

Roy and his brother Frank Farmer were innovators. They received a patent for a new type of roaster and started another company called Western Urn Manufacturing. That plant would be converted during World War II into a maker of ejection seats for fighter planes, according to the company video.

Before the war, Farmer Brothers did more than hold its own through the economic depression of the 1930s, managing to expand its turf outside California. By 1939, Farmers was roasting and selling more than 3 million pounds of coffee. Starbucks wouldn't sell its first cup for another 32 years (via Starbucks).

Thanks to a postwar boom, Farmer Brothers in 1949 was able to build a 20-acre headquarters and state-of-the-art manufacturing plant in Torrance, California. The company stayed on the coffee industry's leading edge. In 1965, Western Urn Manufacturing created the Brewmatic, designed to brew larger quantities of coffee at restaurants and cafeterias.

The son of Farmer Brothers' founder wasn't ready to take over

The second half of Farmer Brothers' history has been about expansion. By the time the company was celebrating its 75th anniversary, in 1987, it was selling coffee, tea, spices, and related equipment to three-quarters of the United States, according to the video the company made on the occasion of its 100th birthday.

But recent history also has controversy and even a little mystery. Roy F. Farmer took over his father Roy E. Farmer's business in 1951, after the founder died. A company history on the website Funding Universe, which cites the International Directory of Company Histories, reports that son Roy was not up to the task of leading Farmer Brothers — even though he had held all kinds of jobs at the company since high school (via Legacy).

The Farmer family couldn't pay the estate taxes that came due after Roy E.'s death, and his son was forced to sell shares of the company to the public. Then came a major blunder: Roy F. accepted a shipment of low-quality Cuban beans that made an undrinkable cup of coffee. Through trial and error, Farmer found a way to blend good coffee beans with the bad ones to mask the poor flavor. This method of fixing a big mistake became standard practice, according to the Los Angeles Times. By hiding cheap beans in its blends, Farmer Brothers became known for what the newspaper called a "decidedly average" cup of coffee.

The son of Farmer Brothers' founder battled shareholders and family members

A decisive proportion of Farmer Brothers stock remained in family control, and Roy F. ran the business more like a dictatorship than a publicly traded company. After 50 years of this, shareholders revolted. For reasons perhaps only known to Farmer and his closest family members, the business in 2002 was sitting on nearly $300 million in cash, which was a whopping 70 percent of the company's total worth, according to Funding Universe. One investor holding Farmer Brothers stock told the Los Angeles Times, "This looks like an old coffee company that has become a pile of cash and a small coffee company." Shareholders wanted Farmer Brothers to use that cash either to buy competitors and expand, or else pay them big dividends.

Roy F. Farmer was even fighting with his own family. The Los Angeles Times reported in 2003 that his sister's son, Steven Crowe, sued to gain better control of his side of the family's 9.8 percent share of the company. Even though those shares belonged to Crowe and his sister, Farmer controlled their voting power. "Farmer is abusing his power ... to solidify his dominance over Farmer Brothers," Crowe's attorney told the Times. By early 2004, Farmer would settle the dispute by buying out the Crowes for $111 million (via Los Angeles Times).

The family lost its tight grip on Farmer Brothers coffee

Critics said Roy F. Farmer was falling behind the times. The company had stopped innovating and was ignoring the growing threat posed by Starbucks (via Los Angeles Times). Despite this, friends and rivals alike praised Roy F. Farmer after his death in March 2004. He pioneered high-speed, efficient ways to roast and package coffee, which led to growth on a scale no one had foreseen. Farmer Brothers was in 29 states by the time Farmer died.

After Farmer's death, his son, Roy E. Farmer, died under mysterious circumstances less than a year later. The company wouldn't comment on what had happened (via Los Angeles Business Journal), but this much was clear: The Farmer family was rapidly losing its grip on the business, and its future had never been more uncertain.

After the third-generation Roy E. Farmer's untimely death, someone not named Farmer led the company for the first time in its 93-year history. But Guenter Berger was no outsider. According to an online forum for Farmer Brothers shareholders, Berger had been with the company for 44 years.

Farmer Brothers struggled under new leadership. An update posted to the shareholders forum almost three years after Berger took over said the company was losing money and losing market share to the competition. Almost half of that $300 million pile of cash was gone, too, with little to show for it.

Farmer Brothers found a path to profitability in the 21st century

Farmer Brothers did accomplish something significant during this period, acquiring a high-end coffee company from Portland, Oregon called Coffee Bean International, according to CSP. Some people in the company apparently realized they needed to respond to the Starbucks threat after all. "We believe CBI will help re-ignite the growth of Farmer Brothers by establishing an immediate presence in the fast-growing market for specialty coffee," the company's president said. Farmer Brothers sealed the deal in 2007, paying $22 million cash (via CSP).

Over the next decade, Farmer Brothers continued to pursue a strategy of growth through acquisitions. In 2009, it took over part of Sara Lee. At the time Sara Lee, known mostly for its frozen desserts, competed directly with Farmer Brothers in the foodservice coffee business. By acquiring that piece of Sara Lee for another $45 million, Farmer Brothers knocked out a major competitor and instantly gained 20,000 customers (via CSP).

Farmer Brothers wouldn't start turning a profit, however, until Mike Keown took over as CEO in 2012 (via The Dallas Morning News). Keown continued Farmer Brothers' expansion. He acquired another competitor, Boyd Coffee Company, in 2017 (via Globe Newswire). The company also acquired the specialty tea company China Mist in 2016 (via The Dallas Morning News).

Farmer Brothers' move to Texas meant mass layoffs

In the past six years, Farmer Brothers made the biggest move in the company's history — a move previous generations couldn't have imagined. And we do mean "move." In February 2015, Farmer Brothers told the 350 employees at its home base in Torrance, California that the company was relocating to Texas. By the way, you're all out of a job, too. Farmer Brothers did transfer more than two dozen Torrance employees to the new headquarters in Northlake, Texas (via The Dallas Morning News), but nobody knew that when they first got the news. "The way they did it was brutal," an employee told The Los Angeles Times. "There was security everywhere making sure we got in our cars and drove away."

Nothing personal to the 300-plus who lost their good-paying jobs — the move was strictly business. Texas had a friendlier business climate, and Farmer Brothers expected to save $20 million a year (via The Dallas Morning News).

Carol Farmer Waite, a granddaughter of the company's founder, said the mass layoffs in California were not the Farmer Brothers way, especially when considered with recent pay raises for top executives. "These are all practices that my father and grandfather would never have dreamed of," she said, according to The Dallas Morning News.

COVID-19 hit Farmer Brothers hard

Poised in Texas to continue its streak of profitable years, the company was hit with something it hadn't seen since the days when two brothers delivered coffee to restaurants in horse-drawn carriages: a global pandemic.

Farmer Brothers was especially vulnerable to the effects of COVID-19. Its biggest clients, those hotels, restaurants, and casinos, were heavily curtailed or completely shut down. In response, Farmer Brothers temporarily cut its workforce nearly in half. Executives made a more modest sacrifice — a 15 percent pay cut (via The Dallas Morning News). Almost a year after the pandemic started, Farmer Brothers reported sales were still down 31.4 percent. The company put a positive spin on this news, calling it a significant improvement over the 65 to 70 percent sales drop it saw in April 2020.

Stock market observers were optimistic, however. An analyst at Seeking Alpha said a recent deal to distribute some of High Brew Coffee's cold-brew flavors could mean record sales for Farmer Brothers — once the pandemic is over, that is.

When that time comes, people will return in large numbers to hotel lobbies and once again pull cups of hot coffee from unlabeled dispensers. They'll be back at the casino tables, ordering cups of Joe to stay focused. And Farmer Brothers hopes that you'll be enjoying one of their blends, whether you know it or not.