Mistakes Everyone Makes When Trying To Read Food Labels

It's tempting to cruise through the grocery store aisles as quickly as possible, grabbing your go-to foods without more than a cursory glance at the label. Surely if the packaging screams, "Good source of protein!", "Gluten free!", or "All natural," it's worth bringing home and sharing with your family, right?

Well, not so fast. Packaged and processed foods are a big business, and food marketers know how to finesse the system to make those not-so-healthy options look a little more appealing. And unless you take the time to read the food labels thoroughly — the front and the back of the box — you may end up consuming too much of products or nutrients you know you should steer clear of, like salt, saturated fat, or sugar. And while there are high-quality, healthy options available for packaged foods — items that make day-to-day life a little easier so you're not forced to cook everything from scratch — the reality is you should try to limit processed (i.e., packaged) foods and stick as much as possible to fresher fare with labels you don't have to try to interpret. A bag of carrots is just a bag of carrots, right?

But even if you already take the time to look over labels, chances are there a couple of things you're missing. This is because labels can be inherently confusing, making it hard to differentiate the important information from the less important. So the next time you hit the grocery store, this is what you need to consider.

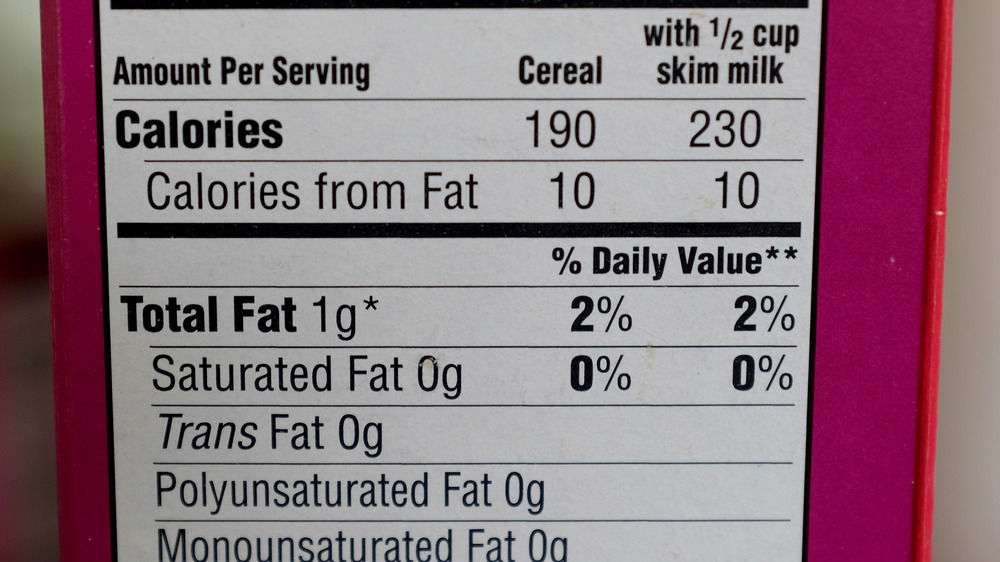

Skipping over serving size

Understanding how many servings are in a container, and how large a serving size is, can make all the difference in understanding what you're really consuming when you sit dive into a bag of chips or bowl of cereal. All of the other information provided on the label (calories, fat, sodium, and so on) is based on a single serving. But often, a serving is less than you might assume. For instance, in a standard container of Pringles, a serving is 16 crisps, and there are about five servings per container. If you've been known to sit down and eat half a canister at a time (who hasn't been there?), you're actually consuming 2.5 servings worth, which translates to 375 calories and 22.5 grams of fat.

And even if you buy what looks like a single-serve package of something, check the serving size. Often packages of nuts or chips you buy at convenience stores or you grab from the check-out lane contain two or three servings per container. As Jen Bruning, MS, RDN, LDN, spokeswoman for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics told The Healthy, "Even with small items like candy bars, it's important to see how many servings are in your hand. Just because it can fit in your hand or you can eat it in one sitting doesn't mean it fits one serving size by nutrition." And not paying attention to these details is a surefire way to inadvertently overeat.

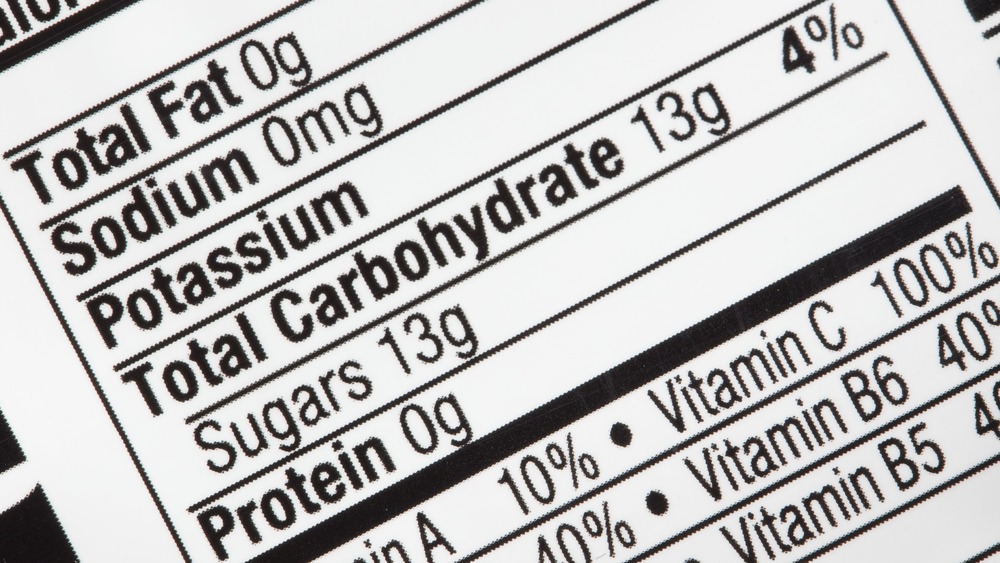

Misunderstanding what Percent Daily Value really means

Another way to misinterpret food labels and nutrition information is to incorrectly read the "% Daily Value" (%DV) information on food labels. As explained on the National Institutes of Health website, Percent Daily Value is an estimate to provide consumers with a quick way to estimate whether they're getting enough of (or too much of) key nutrients. The problem, though, with misinterpreting this number is two-fold.

First, the reference number is based on a 2,000 calorie diet. For individuals who regularly consume more or less than 2,000 calories, these percentage values won't line up. As the NIH website explains, "If you are eating fewer calories and eat a serving of this food, your %DV will be higher than what you see on the label." And if you're consuming more calories, the %DV will be lower. So if you're using %DV to help guide you in your food nutrient intake, but you don't know how many calories you regularly consume per day, the guideline won't be terribly helpful. To make this process easier, keeping a food log through an app like MyFitnessPal can help you track your intake and automatically calculate your %DV based on your real data, rather than an estimate. Plus, these apps calculate all the percentages for you, so you aren't forced to try to do the math on your own.

You only read the front of the package

It's incredibly tempting to scan the front of the packages you pick up without bothering to pay attention to the more confusing fine print located on the back. To be fair, there's a lot of information to be gleaned from the front of packages, but it can be incredibly misleading if you're not aware of common food marketing tactics. For instance, food marketers know what types of diets are trending, and adjust labels to draw people in. Have you ever noticed "gluten-free" on a bag of baby carrots or apple slices? Carrots and apples have always been naturally gluten-free, but it wasn't until gluten-free diets became popular that food marketers started adding this label to the packages.

And just because an item flashes "all natural" or "organic" on the front of its packaging, that doesn't mean the nutritional content is healthy. A cookie is a cookie, whether it's organic or not, and cookies typically come with lots of added fats and sugars. Chowing down on gluten-free cookies likely is no healthier than a gluten-filled variety. As Keri Gans, a registered dietitian and the owner of Keri Gans Nutrition told Eat This, Not That!, "Just because it's made from organic ingredients doesn't mean it's less likely to make you gain weight."

Falling for food marketing ploys

Food marketers will do practically anything to paint their products in a healthy light. Often, this is with front-of-package labeling that makes claims about health-related content. Food marketers might highlight a single nutrient, like carbohydrates, to imply that the product is "low carb," or they might claim their product is "made with real fruit," or features calorie-free sweeteners like Splenda. Food marketers will basically do anything they can legally get away with to increase the odds that you'll throw their product into your cart, rather than the product of the competition. That's why it's wise to ignore front-of-package claims, and take a more full assessment by reading the complete nutrition label.

For instance, "made with real fruit," or "contains fruit juice" doesn't mean the product is 100-percent fruit. As Jen Bruning, licensed dietitian nutritionist, and spokeswoman for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics told The Healthy, "It can say 'made with real fruit,' and real fruit is included in that product, but that doesn't mean there aren't other things. You still want to check the ingredient list and see what else is there."

Take, for instance, Sunny D. This fruit drink makes claims like, "100% vitamin C per serving," and "orange-flavored citrus punch with other natural flavors" on the front of the label, but one quick glance at the back notes that it only contains 5 percent juice, and of the 14 grams of sugar per serving, 12 grams are added sugars, not from fruit itself.

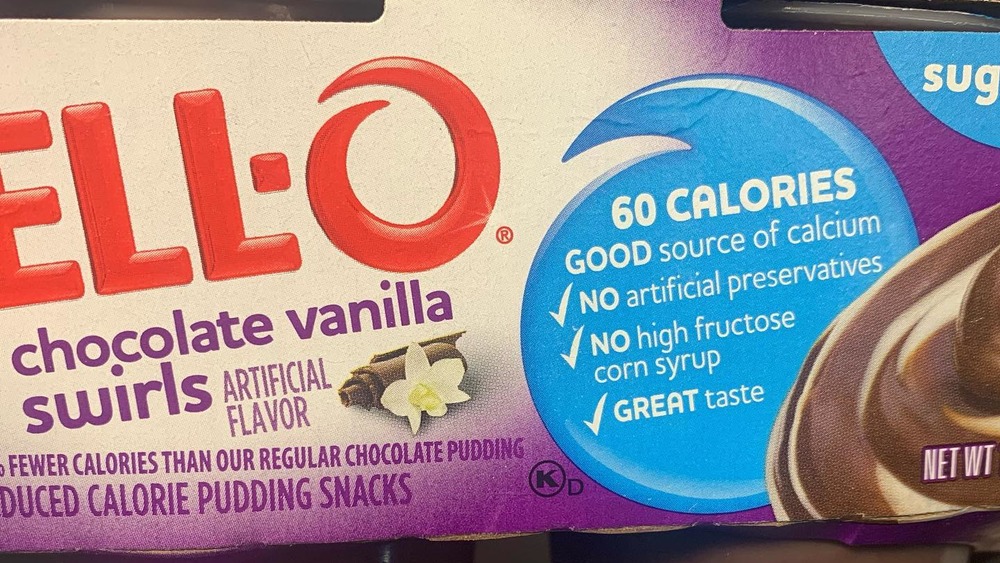

Assuming "good source of" labels automatically make the food healthy

Using the phrase "good source of" on the front of a food package is another food marketing ploy designed to catch your attention and make you consider purchasing a product that might otherwise have some nutritional red flags. Think about it — almost every food will be a decent source of one or two nutrients — for instance, calcium, protein, or vitamin C. In some cases, these nutrients occur naturally, but in other cases, manufacturers add them to boost the nutritional (and marketing) value of the product. But to focus on a single nutrient, and not consider the other ingredients in the product or the nutritional value of the food as a whole, is a good way to end up consuming added fat, sugar, sodium, or calories that you'd be better off avoiding.

Consumer Reports points out how the "good source of" phrasing can be used for good or for ill when used on plain yogurt packaging versus cookie packaging, "Highlighting the calcium content on plain yogurt is one thing because overall, plain yogurt is a healthy food and calcium is naturally present," the site says. Then it notes that Stella D'oro Breakfast Treats also claim to be a good source of calcium, but it's calcium that's been added to the product, and with 90 calories, six grams of sugar, and zero grams of fiber, all-in-all, "the cookie is far from a health food." It's just another example of "buyer beware."

You think zero grams trans fat is always the truth

While the front of food labels can be misleading due to marketing claims, the back of food labels is occasionally tricky as well. This is most evident when it comes to labels that read "0 grams trans fats." As explained by NPR, trans fats are the worst types of fats you can consume because they increase bad-for-you cholesterol (LDL), decrease good-for-you cholesterol (HDL), and raise triglycerides. As such, the FDA started requiring the inclusion of trans fats on labels in 2006, and in response, companies reformulated product ingredients to significantly decrease trans fat content.

That said, there's a loophole. Because trans fats occur naturally in some foods, the FDA allows products with less than .5 grams of fat per serving to use the "0 grams trans fat" terminology. This may not seem like a big deal — if a food has .4 grams of trans fat per serving, it's unlikely to cause major damage. The problem is if you're eating a lot of processed foods. As NPR summarizes, consuming 8 grams of trans fats per day on a 2,000 calorie daily diet can negatively impact cholesterol. With hidden trans fats, "an adult who has coffee cake in the morning, cookies with lunch and then some fries at dinner" could easily hit this mark.

The solution? Read ingredient lists. Whenever you see "partially hydrogenated" in the ingredients, that's a sign that the product contains trans fats.

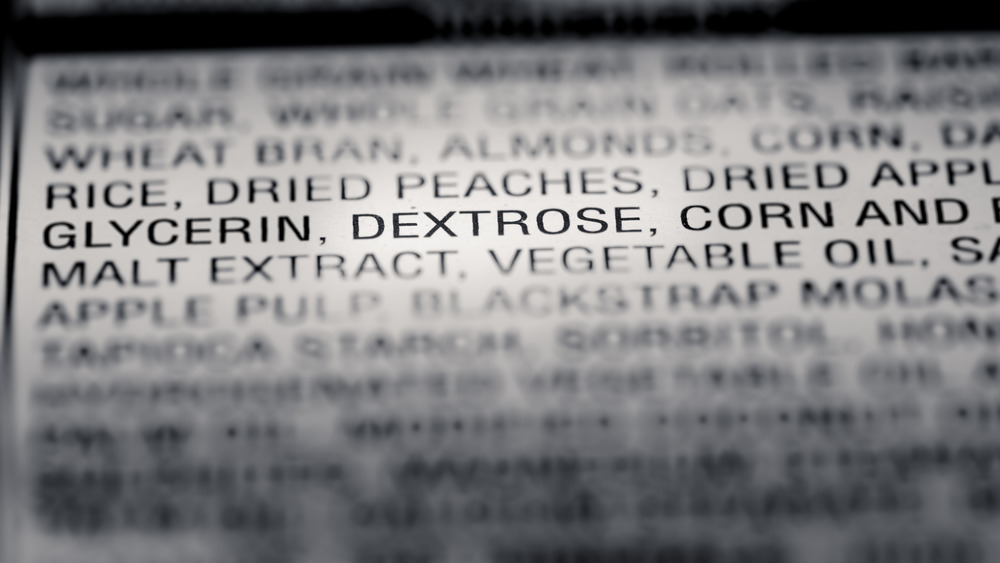

You don't read the ingredient lists

Labels provide lots of information about the nutritional content of your food, but if you're reading labels without noting the ingredient lists, you're missing out on critical information. First of all, the ingredients listed are listed in order of weight. As in, which items are most prevalent in the product. Second, ingredient lists can give you a clue as to whether there are hidden trans fats or sugars, or highly processed additives in the product. Generally speaking, if it's hard to pronounce an ingredient in a food, you may be better off skipping the food altogether.

But that brings up another issue — as soon as ingredients become harder to pronounce or interpret on a list, you're more likely to "tune them out," and simply focus on the first couple ingredients you can read. Elana Natker, a registered dietitian who spoke with Eat This, Not That! explained, "You don't want to ignore the end of the ingredient list because this is where you're going to find your added vitamins or the smaller weighted things." Things like artificial sweeteners, like sucralose and aspartame, or monosodium glutamate.

Also, the ingredient list is where you can sniff out claims about "multi-grain" or "wheat" products — many of which primarily use enriched wheat flour rather than 100-percent whole grains. Unless the label says 100-percent whole grains or includes whole grains or whole wheat as the first listed ingredient, it's not going to be as healthy as you think.

Buying "cage free" or "vegetarian fed" eggs

Unless you're paying close attention to the food industry's labeling guidelines for eggs, egg carton labels can be exceedingly confusing. There's "free range," "cage free," "vegetarian fed," "pasture raised," "farm fresh," and "natural," just to name a few of the buzzwords. So how do you know which carton to buy?

First things first, according to the Humane Society, "cage free" does not mean the chickens laying the eggs have access to natural, outdoor spaces. These chickens are usually kept in large buildings, in close quarters with many other chickens. They may also be subject to beak cutting and starvation-based forced molting. If the humane treatment of animals is important to you, you'd be better off looking for labels that say "free-range/free roaming," "pasture raised," or "certified organic." You may also want to look for labels from voluntary certification programs, like "American Humane Certified" or "Certified Humane" that verify the hens are being treated humanely.

Second, it's worth skipping eggs that are labeled "vegetarian-fed" or "vegan-fed." Maria Marlowe, author of The Real Food Grocery Guide, explained to Well + Good, "Chickens are not naturally vegetarians, meaning this diet deprives them of a natural food source and thus isn't necessarily good for their health." Plus, in a natural environment, chickens eat worms and insects, so a label that indicates "vegetarian fed," even when paired with "free-range," may be a signal that the chickens aren't being given adequate access to the outdoors.

Noting the carb count, but not noting which parts are sugars and which are fibers

Carbs have gotten a bad rap. It's unfortunate, really. Carbohydrates are one of only three essential macronutrients — fats, proteins, and carbs — and they play an essential role in energy metabolism. In fact, almost every naturally grown food — fruits, vegetables, and whole grains — is primarily made of carbohydrates. This is why noting the carbohydrate content on a food label, but failing to look at what type of carbohydrate the food provides, is such a big label-reading mistake.

Of course, labels won't necessarily break down exactly what type of carbohydrate the food contains (such as monosaccharides, disaccharides, or polysaccharides), but it will tell you how much of the total carb content is derived from sugars or fiber. Most Americans consume too much sugar and too little fiber in their diets, so as pointed out by Prevention, you want to look at how much of the carbs you're consuming are coming from sugars or fiber. A good rule of thumb is to look for products where sugar content comprises less than 25 percent of total carbs per serving, and to look for items that have at least four to five grams of fiber per serving. Fiber that occurs naturally, and isn't added as a nutrition "bonus" during processing will come from whole grains, fruits, and vegetables.

Not understanding what "made with organic ingredients" means

"Organic" is another one of the most popular food marketing buzzwords that can be highly misleading. As explained by Farm Aid, foods that are labeled with the USDA's Organic Seal must contain at least 95 percent organic ingredients. These foods can't include or have been raised with synthetic growth hormones, antibiotics, pesticides, biotechnology, synthetic ingredients, or irradiation in production or processing. But even products with the USDA Organic Seal can include up to 5 percent ingredients that fail to meet these guidelines.

Second, foods that are labeled with "made with organic ingredients," but don't include the UDSA Organic Seal, only need to contain 70 percent organic ingredients. That means up to 30 percent of the ingredients don't have to be organic. So if eating organically-produced food is extremely important to you, you're best off seeking out the items with the official USDA Organic Seal or looking for local farmers in your area who pride themselves on maintaining organic practices with their animals and plants.

Finally, just because an item is "organic," that doesn't mean it's healthy. A cake made with organic ingredients is still a cake. Chips with an organic seal are still chips. These products are still likely to contain high levels of fat, salt, and calories, and aren't likely to offer much in the way of key vitamins and minerals. If you're going to eat organic, great. Just try to stick to organic fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and meats, not highly-processed foods.