The Real Reason Your Wagyu Beef Is Probably Fake

There is perhaps no more famous type of beef than wagyu. The Japanese beef is widely considered the creme de la creme when it comes to all things bovine, with the highest grades costing up to $200 per pound, according to Business Insider. All that cost is for good reason, as real wagyu is a genuine treat for steak lovers with marbling unlike any other type of beef. Yet the high cost the meat demands — mixed with a general confusion outside of Japan about what, exactly, "wagyu" is — means that there are also plenty of businesses out there peddling fake wagyu.

True wagyu from Japan is rare thanks to strict regulations and both global and domestic demand. The name recognition is undeniable, however, and it seems to appear on menus across the United States. Some of the wagyu sold is real, some of it, though, may have misleading labeling and be entirely fake.

Here's how you can tell if your wagyu beef is fake, and why it garners so much attention from consumers and those who try to capitalize on wagyu's popularity.

There are technically many different types of regional wagyu

The first thing you need to know is that there is no one wagyu. In Japanese, "wagyu" literally translates to Japanese cow. Just like how some countries classify wine and cheese by region, Japan differentiates its beef by region — and there are many types with slightly different regulations, according to Japan's governmental travel resource. Also like regionally designated wines and cheeses, the production of certain types of wagyu is limited to a certain area. As Champagne can only come from Champagne, France, certain wagyu can only come from certain parts of Japan.

The most well-known type of wagyu in America is Kobe. Kobe beef comes from the region around the city of Kobe in Hyogo Prefecture. The cows are fed rice and corn, and the meat is known for its sweetness and marbling. Ohmi from the Shiga Prefecture is another famous wagyu with a fine grain, and it was once given medicinally in the 1800s to the shogun ruling class before beef became widely available. And then there's Matsusaka Ushi, which comes from Matsusaka City in Mie Prefecture. The cows there are fed beer and given intense care for a high fat-to-meat ratio.

While those three are the most famous, they aren't the only types of wagyu. There's Yonezawagyu from Yamagata Prefecture, Hitachigyu from Ibaraki Prefecture, Kazusa from Chiba Prefecture, Miyazakigyu from Miyazaki Prefecture, Kumamoto Akaushi from Kumamoto Prefecture, and others.

There's a good chance your wagyu is labeled incorrectly

When it comes to wagyu, the label may be more than a little misleading. In the mid-2010s, some of New York City's most famous steakhouses and restaurants were listing "Kobe" wagyu beef on their menus. An investigation by Inside Edition brought one problem to light, however: places like Old Homestead Steakhouse and Le Bernardin weren't serving true Kobe wagyu beef like what was listed on the menu. The restaurant brand McCormick & Schmick's was doing the same, and it had to settle a class-action lawsuit because of it.

The problem comes down to labeling regulations set by the United States Department of Agriculture. The law states that beef only has to have 46.9 percent wagyu genetics to sell as wagyu at retail, according to Bon Appetit, and the rest can be angus. Restaurants don't have to listen to these labeling regulations at all and can call whatever beef they wish wagyu. This makes wading through wagyu beef labels like walking through the Wild West of questionable information.

If you're looking to make sure you're definitely getting the real thing, look for "from Japan" on the label. Kobe wagyu that doesn't say "from Japan" isn't actually Kobe. As Larry Olmsted writes for Bon Appetit, if you're not in one of the few restaurants certified to sell the imported Kobe beef, "simply assume any Kobe beef claim is a lie, especially 'Kobe' burgers and hot dogs."

There's more than one rating system to classify wagyu beef

Real wagyu is rated by multiple strict systems in Japan. The first to pay attention to is if the meat is A, B, or C. The letter represents the yield from the cow — A has the highest yield, C is the lowest, and B is somewhere in the middle. This isn't the most pertinent information for consumers, but it means a lot to the people sourcing the meat, with A being more desirable.

The second system is a one through five number that follows the letter grade. Wagyu typically has an A4 or A5 (A5 being the highest), according to Robb Report. This is where things get a little complicated, since that number is based on another number-based rating system called the Beef Marbling Standard. The Beef Marbling Standard goes from 1 to 12, with 12 being the highest level of fat marbling. The A5 rating requires a Beef Marbling Standard rating of 8 to 12, while A4 requires a rating of 6 to 8. This makes an A5 12 piece of wagyu the highest you can purchase.

These ratings aren't taken lightly in Japan and it takes three years of training to become a rater, and each cow is rated by three of these highly trained raters.

American beef grades don't go as high as the beef grades in Japan

The United States Department of Agriculture is responsible for the beef grading system in the country. The grades let consumers know the quality of the meat, and the most common from lowest to highest are Select, Choice, and Prime. Lower grades, from lowest to highest, include Canner, Cutter, Utility, Commercial, and Standard.

How they get those grades all depends on the yield, fat marbling, age, and other quality factors, according to the American Wagyu Association. Even the highest American classification can't account for the fat marbling in wagyu beef from Japan, however. That marbling is part of the reason Japan uses such an intense rating system with the letter rating, the number rating, and the Beef Marbling Standard rating.

That's not to say the domestic rating system is bad. The three main ratings are further broken down into plus, neutral, and minus. Texas A&M University has a breakdown of the beef grading system that shows how even the best grade of beef in the U.S., Prime, is classified by abundant marbling, moderately abundant, and slightly abundant. Still, when you're looking at the very top of the line wagyu, you'll need the Japanese rating system to adequately convey the level of fat marbling in the meat because only the Japanese system can grade such a high level of fat marbling.

For wagyu, it all depends on the breed of the cow

Even though wagyu translates to Japanese cow, not all Japanese cows make it into the classification. Only four breeds get that special designation, according to the American Wagyu Association: Japanese Black, Japanese Brown (also called Red Wagyu in the U.S.), Japanese Polled, and Japanese Shorthorn. Japan makes sure their cow breeds remain the way they are, and progeny testing (meaning testing the parents of each animal) is mandatory to keep the genetic line perfect. The most sought after types of wagyu — Matsusaka Ushi, Kobe, and Ohmi — all come from Tajima beef, which is a subspecies of Japanese Black from Hyogo Prefecture.

Regionality defines each breed, according to the American Wagyu Association. Other popular strains of Japanese Black cattle include Shimane (from Okayama Prefecture) and Kedaka (from Tottori Prefecture). Japanese Brown cattle lines include Kochi, which Oklahoma State University's agriculture department notes is influenced by Korean strains of cattle, and Kumamoto, which is influenced by a Swiss breed of cow. The Japanese Black cows are genetically unique, however, and something in their DNA causes the fat in their body to intermingle with the muscles rather than gather in a fat cap like other cows, according to Robb Report.

Breeding is tightly controlled by region and the cows and their offspring are kept inside the country. Each calf has an identification number that links the animal to the farm it was born at, along with the cow's birthday and bloodline.

There's a difference between wagyu and American wagyu

While Japanese imported wagyu is the surest way to know it's the real stuff, there is an American version. According to Oklahoma State University's agriculture department, two Tottori Black wagyu and two Kumamoto Red wagyu bulls were imported to the U.S. in 1976. Then, in 1993, five Tajima cows (two male, three female) were brought in, and 35 more cattle of various Japanese bloodlines made it to American farms in 1994.

Unlike the cows in Japan that were carefully kept apart to make sure the bloodlines stayed the same, the wagyu in the States were crossbred with angus cattle. This has led to the nickname "wangus". According to Robb Report, American wagyu is heavily marbled, but lacks the same consistency, marbling, and flavor as the Japanese wagyu that's so heavily regulated.

"The American stuff is wonderful," Joe Heitzeberg, co-founder and CEO of Crowd Cow, told Robb Report. "You can eat more of it. With the Japanese stuff, because it's so fatty and rich, most people can't eat more than a few bites of it before it's so overwhelming. So if you're in the mood for a steak dinner, and you want a giant steak, you can't really do that with Japanese wagyu."

American crossbreeding is more of an availability issue than anything else. George Owen, executive director of the American Wagyu Association, told Food & Wine that most full-breed wagyu is used for breeding because there are so few of them.

Only a select number of American restaurants can serve the highest grades of beef

Kobe, one of the types of wagyu that people especially chase after, is really difficult to get in the United States. Despite how hard it is today, it was even harder a decade ago. For a period of time in the 2000s, it was illegal to import Kobe beef from Japan, which is the only place real Kobe beef can come from since it must be cut from cows in Hyogo Prefecture.

Things aren't quite as dire for Americans who want true Kobe wagyu beef today, but it's still difficult. According to Robb Report, the Kobe Beef Association only certifies approximately 5,000 cows annually as Kobe beef quality. All true Kobe beef is born, raised, and slaughtered in Hyogo Prefecture before being graded according to strict regulations. It's also tracked and only sold to certified retailers and restaurants. That doesn't leave a whole lot of beef to go around for all of the people the world over who want a taste.

Robb Report notes that there are only 32 restaurants in America certified to sell Kobe beef. New York City (212 Steakhouse), Dallas (Nick & Sam's Steakhouse), Las Vegas (Wolfgang Puck), and Los Angeles (Shibumi) are a few of the cities where you can find restaurants that sell Kobe beef. Ask to see the 10-digit certificate of authenticity that any restaurant selling Kobe beef will have to guarantee it's the real deal.

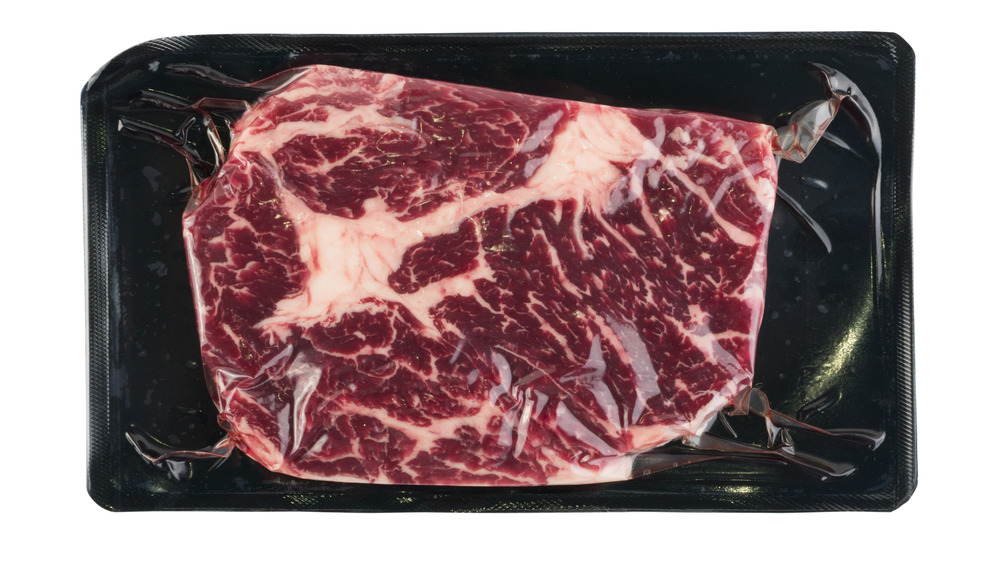

Authentic wagyu beef has a distinct appearance

All of that fat that makes wagyu so desirable gives an umami sweetness to the beef. It also adds a very distinctive quality that is noticeable right off the bat even before you get a taste (if you get to have a taste at all): it's riddled with white webs of fat. In fact, instead of the deep, iron-red color that you're probably used to seeing, wagyu can come off slightly pink because of the different ratio of white fat and red meat.

Another giveaway that you can tell just from the sight is that wagyu beef imported from Japan is always boneless, according to Real Simple. That makes it an easy spot compared to all the T-bone, rib eyes, strip steaks, and other bone-in cuts sold on the meat aisle of the grocery store or butcher shop.

According to Bon Appetit, these are the things to look for when seeking a true piece of wagyu: evenly dispersed fat (dots, a spider web, or thin veins are all apt comparisons) and a "uniformly pink" color that showcases an integrated ratio of meat and fat. Don't assume wagyu is all that bad for you just because of its high fat content, either. Wagyu has a high level of unsaturated fatty acids like oleic acid making it slightly healthier with the added bonus of having a melting point that's lower than the standard human body temperature of 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit.

Even true American wagyu can undergo genetic testing

While it is true that American wagyu doesn't undergo the same detail heavy genetic tests and cattle lineage reports that wagyu from Japan does, that doesn't mean American wagyu is a total testing free for all. Members of the American Wagyu Association can submit for genetic testing and parent verification to be registered as pure-bred wagyu.

American Wagyu Association's 2020 breeders book is filled with companies that certify wagyu cattle for breeding and for eating. Companies like Y2 Wagyu have both Black Wagyu and Akaushi (another name for Japanese Brown). The testing and certification is run through the American Wagyu Association, and can only be done for members for a set fee for each test, certification document, and grading.

It's more than taste, too. The 2020 breeders book states that ranchers appreciate wagyu "for their exceptional calving ease, longevity, health benefits, and premium carcass quality in a single cross which no other beef breed can offer."

Wagyu beef is raised in a very specific way

In the days when fake Kobe beef and wagyu were being routinely passed off as the real thing, rumors swirled about why the meat was so special. Some said the cows were given massages or had a diet of beer and sake. All of it was meant to result in less stressed cows and therefore a better cut of beef. Most of those claims were either exaggerated or flat out lies. Still, wagyu cows from Japan do undergo a good bit of pampering.

The Wagyu Shop notes that breeders in Japan do in fact do everything they can to make each cow's life as stress-free as possible. They get a high-energy diet and have plenty of safe space so they don't burn fat and develop too many muscles. Breeders control the noise, supply clean water, separate animals that fight, and monitor the animals multiple times a day, according to Robb Report.

"[Crowd Cow] works with farms that will check animals every four hours," Heitzeberg told Robb Report. "In America, if you're in Montana with a thousand-plus acres, you may not see your animals for seven days. They're out there foraging on the natural Montana grasses, but you don't know what else they're doing."

As for the rumors about beer, there is a kernel of truth to that. Japan's tourism website notes that Matsusaka Ushi wagyu is famously given beer "to increase their appetites."

Real wagyu comes in many cuts you might not be familiar with

Steak fans know the best cuts of beef. Even people who only eat beef occasionally typically know some of the most famous, like rib eye, filet mignon, and New York strip steak. Every country has slightly different cuts, though, and the same is true with some cuts of wagyu imported from Japan.

There are a few especially popular cuts, according to Live Japan. Sirloin (sāroin in Japanese) is popular as a steak, while rib roast (riburōsu) is popular in the Japanese fondue called shabu-shabu. Haneshita (which comes from a similar area as the chuck flap) is another prime cut, and the same goes for kainomi (the bottom flap of the ribs). There is also, of course, the offal. Wagyu offal is divided into 22 sections, according to the site Tsunagu Japan, which are found from the tongue to the intestines.

One of the best ways to taste all of the different cuts of wagyu in Japan is to go to a yakiniku, which is kind of like a Japanese barbecue spot.