Sneaky Ways Your Butcher Is Scamming You

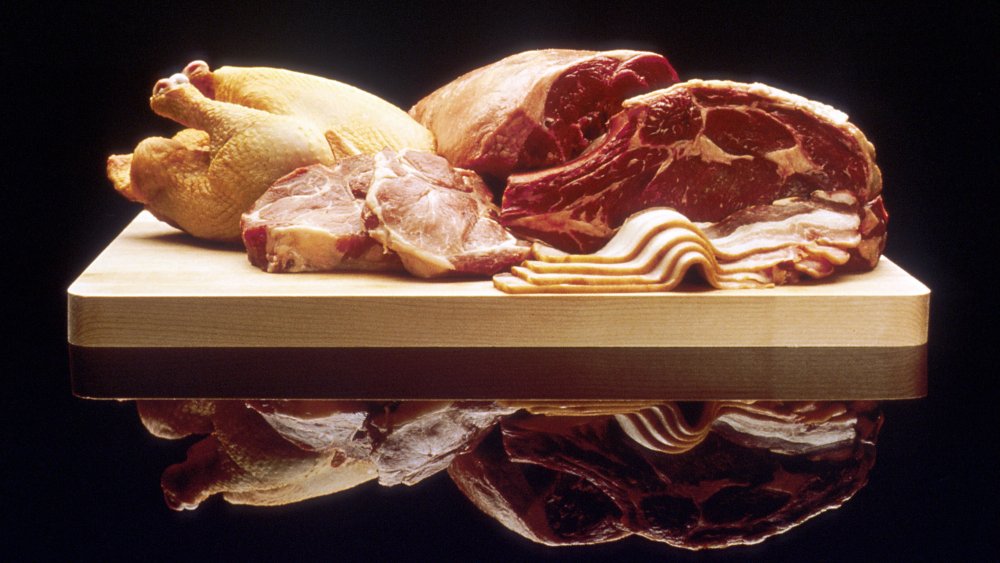

Buying meat from your local butcher seems like a pretty simple proposition. You decide what you want to eat, stroll into the store, and select the cut you want from the case. Maybe, if you're feeling adventurous, you might ask the butcher a few questions.

Is it that easy, however? For the unwary customer, a few pitfalls lay in wait. For instance, how sure are you that the meat is fresh? Butchers and meatpackers can use tricks like infusing packaging with small amounts of carbon monoxide, plumping cuts up with salt solutions, and simply trimming and flipping a cut to hide the sketchy bits. Moreover, things that are sold as great deals, like individually cut steaks, maybe aren't such money-savers, after all.

Now, this is not to say that all butchers are evil villains who want to sell you rotten meat, a la Upton Sinclair's The Jungle. However, they are obliged to sell meat as quickly as possible, which means that they need to take on generally legal tactics that nevertheless have a whiff of a sneaky scam about them.

Things aren't quite so dire as you may believe, thankfully. A little dedication to reading labels, speaking to your butcher, and staying informed can make a big difference. Overall, it can help you buy the best cuts of meat and at a genuinely good price, too. Plus, if you ask nicely and know a reputable butcher, you could learn how to shop with the best of them.

Butchers may use carbon monoxide to make meat look fresh in the package

What makes a piece of meat look its best in the butcher case or on its little styrofoam tray? You may believe that it's just the meat itself. You may also consider how long it's been sitting there, its overall color, or, for the eagle-eyed amongst you, the fine print on the labels. The true answer is more complicated. For some butchers, their secret tool is none other than carbon monoxide.

Why have carbon monoxide there in the first place? According to the journal Foods, some plants have pumped a small amount of carbon monoxide, or CO, into packaging in an attempt to keep things looking fresh. Without it, the meat may begin to oxidize and turn brown, making it look downright gross in the grocery store. Keeping that fresh-looking red color is the goal of modified atmosphere packaging, which can use CO along with carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and oxygen.

According to ABC News, the small amount of CO that might be in your package of steak is itself harmless to the consumer. However, the fact that it can keep meat looking "fresh" for up to 20 days is pretty misleading. In fact, spoilage can still happen even when things look bright red, thanks to CO and modified atmosphere packaging in general. Instead of being potentially fooled by the color of your cut, be sure to take a careful look at the dates printed on the package.

Best-by dates at the butcher counter can be a bit of a stretch

It's a good idea to pay close attention to the dates on the packages at the meat counter. They can tell you when something was packaged and how long it should remain fresh and safe to eat. Then again, you may want to subtract a few days from that best-by date, just to be safe.

That's because, according to the CBC, some grocery stores in Canada in 2014 were found to be padding those dates by a considerable margin. A butcher speaking anonymously with the news service said that his grocery store sometimes relabeled meat, complete with a new date. This is illegal, both in Canada and the United States, but how can you be sure that a manager with poor morals isn't fudging the dates here and there?

This isn't to say that every grocery store out there is illegally messing with the dates at the butcher counter. That said, it couldn't hurt to be cautious. Moreover, be sure you're cooking meat properly. Foodsafety.gov recommends a safe cooking threshold of 160 degrees Fahrenheit internal temperature for ground beef, 165 degrees Fahrenheit for poultry, and 145 degrees Fahrenheit for pork. Steaks, roasts, and chops can also get away with 145 degrees Fahrenheit, with a three-minute rest time. Once you hit these temperatures for enough time without overcooking the meat, you'll be free from worry about many of the food-borne diseases that could be carried by your meat.

London broil isn't an actual butcher's cut of meat

London broil is not a cut of meat. I don't care what the label is saying or what your butcher is trying to say across the meat counter. Officially speaking, says Reader's Digest, there is no such cut. If you happen across a package that claims to contain London broil, it's probably a top round roast. That's a pretty tough steak that, because it's one of those hard-to-chew cuts, is usually offered at a pretty cheap price point. American chef James Beard, in Beard on Food, maintained that "London broil" could also be flank steak, another lean, relatively cheap cut of beef, or sirloin butt, rump steak, or even rib-eye steak. This means that any cost-effective, potentially tough slab of beef could be labeled as the near-mythical "London broil."

If that's the case, then what exactly is "London broil"? According to Carnivore Confidential, it's actually a cooking method. In this case, the chef takes marinated beef, broils it at high heat, then cuts thin strips across the grain. Ideally, this turns a cheap, possibly tough steak into something approaching tender. In Canada, things get even more confusing, as "London broil" might refer to a method where sausage or ground beef is rolled up inside a flank steak and then cooked. Either way, any butcher that tries to tell you a certain cut is London broil may not be the best-informed butcher out there.

'Certified Angus beef' is more butcher marketing than meat

Sure, it may sound good, but that label crowing that a particular slab of meat is "certified Angus beef" means next to nothing. According to a butcher interviewed by Reader's Digest, it's generally considered to be a marketing ploy amongst those in the know.

If all of this "certified" business is a bit of a sham, then what should you look for instead? You'd be better served by going over the U.S. Department of Agriculture's beef grades. It's not as difficult as you may think, though there's plenty of room to get all nerdy about it if that's your thing. Plus, it's an officially federally enforced grading system that doesn't leave too much wiggle room. Generally speaking, USDA "prime" beef is the nicest, especially if you like plenty of marbling from fat. The next step down, "choice" beef, is a little leaner.

"Select" beef is even leaner, though skillful cooking can make it taste plenty good. If you happen to see ungraded beef, that's probably standard or commercial grade as the USDA sees it. Finally, "utility," "cutter," and "canner" grades don't typically make it to the butcher counter, so you're more likely to encounter these grades in processed stuff and ground beef. Ultimately, you need to look for "prime" labels if you want the good stuff.

Give a butcher's discounted meat the side-eye

This may seem old hat to the experienced grocery store shopper, but it bears repeating: be wary of meat on sale. It may seem like a good deal, but you really don't want to play fast and loose with those best-by dates when it comes to raw meat.

The Street maintains that those alluring sale stickers could just be slapped on top of quickly aging meat by butchers who are trying to sell product before it's doomed to the garbage can. Now, if you are pinching pennies or simply love a good deal, it's not the end of the world. First, you'd do well to ask your butcher a couple of questions. Namely, why did this get marked down, and just how old is it, really? Sometimes, you may get lucky and find a perfectly good piece of meat that's been marked down for some innocuous reason unrelated to its age. If it's getting a bit old and you're still set on buying the stuff, be sure to cook it soon, and cook it well.

A butcher's pre-cut steaks are more expensive than a better alternative

It may be convenient for the most harried shopper, but pre-cut steaks and other already sliced meats are a bit of a scam. Yes, of course, no one wants to try and dig into a whole side of beef, but the solution is surprisingly simple. Just nicely ask your butcher to cut it up for you.

According to Reader's Digest, if you can swing the larger overall price, you should really buy a big piece of meat and ask the butcher to cut it up for you. It will take a few extra minutes of your and the butcher's time, but it can save you a shocking amount of money in some cases. For steaks, ask for a nice chunk of top sirloin, and (again, nicely) ask the butcher to cut them into steaks right there. That should be part of the butcher counter service, anyway. You can also ask for cubed meat for stews, individual roast cuts, and even ground beef. Assuming you've got the initial funds and the refrigerator and freezer space, your bank account will be happier with you in the long run.

Butchers pretty up the meat before it hits the case

Butchery is, in many ways, a true art. It's not just some simple hack-and-slash job on various chunks of meat, then thrown carelessly into a case or onto a slab of styrofoam. Butchers need to really know their stuff. They also need to understand how to make meat as pretty as it can be, all so the finished product can grab a shopper's eye before it hits their stomach. It's all part of the grocery shopping game, which is a significant part of their job, after all.

To that end, butchers frequently resort to a few little tricks, says Reader's Digest. That means trimming unsightly fat, cleaning up red liquid, and sometimes just flipping a piece of meat to hide any brown oxidized bits. By the way, according to The Healthy, that red liquid isn't blood at all. Instead, it's a combination of moisture being lost and a red hue from myoglobin, a type of protein found in meat.

Some butchers use a saline solution to plump up a cut

Don't judge a cut by its size. Sure, a piece of chicken or cut of pork may look nice and juicy, but that could be more trickery than substance, thanks to saline.

According to NPR, an estimated 30 percent of poultry, 15 percent of beef, and a staggering 90 percent of pork on sale today is pumped up with a saline solution, composed largely of salt. The idea is that injections of this saline are supposed to increase the overall volume of the meat and also make up for any flavor and liquid lost to overzealous cooking. Visually, consumers are thought to be more interested in a visibly large, juicy piece of chicken, pork, or other meat, even though those looks could be little more than an illusion.

Saline injections can also lead to potentially high sodium levels in your food, Deseret News reports. If you're someone who needs to watch your sodium intake, like people with high blood pressure, that can get pretty dicey fast. Be sure to read the fine print on the meat package label. It's also worth asking your butcher if anything like saline has been added to your cut of meat.

Family packs of meat could mean more work for you

Generally speaking, if you can spend a little more money upfront to buy large quantities of something, you can get a better deal. That's the kind of model that's supported businesses like Costco for many years. Even as an individual shopper out for a good deal, you could potentially save a lot of money by purchasing large pieces of meat and simply asking the butcher to cut it for you.

However, there's one occasion where you may want to think carefully: family packs of meat. As per Insider, pre-cut offerings may not always come out to as good of a deal as you may hope. Of course, given the larger quantities and the price set by your particular butcher, this could work out in your favor. The unglamorous advice? Compare prices, do some math, and always take a close look at the label. You'll also want to make sure that the best-by date isn't too close for your comfort.

If you come across a genuinely good deal on a family pack and you're not going to cook it all right away, you've got some extra work ahead, as you should freeze the leftovers. According to The Kitchn, you should closely wrap each cut in plastic wrap or freezer paper, followed by aluminum foil, and then finally closed up in a zip-top bag. Most meats frozen this way can keep for up to three months before developing the dreaded freezer burn.

The butcher's oldest meat is usually in the front of the display

Imagine you're the butcher. You've got to sell meat at a pretty decent clip or else your store and your job could be in jeopardy. If nothing else, poor sales could mean having a manager breathing down the back of your neck until things start to improve. You've also got to abide by important food safety rules, since making your customers sick is a pretty bad look all around.

Ultimately, this means that you've got to move the older meat out of your realm as quickly as you can. Throwing it out is a loss. If you've got to sell it after it's not totally fresh but not ready to trash, what do you do? Put it in the front of the case.

According to Taste of Home, that's just what many butchers do. You can't blame them, exactly, but maybe you want something fresher. If that's the case, simply reach into the back of the case. Be sure to check the dates on the label, of course, but chances are you will find the freshest stuff a little bit hidden behind the older cuts.

Your butcher might be hiding some cool cuts from you

"Primal" cuts are themselves ever so slightly a bit of a scam. What's a primal cut supposed to be, anyway? According to The Meat Stick, primal cuts are the ones that are first separated from the carcass. A "sub-primal" cut would be one that's made from a primal cut. For example, the eight traditional primal cuts for beef are the chuck, rib, loin, round, flank, short plate, shank, and brisket.

However, so-called primal cuts can actually vary quite a lot, says National Geographic, depending on location, culture, and individual butcher. Perhaps your local butcher isn't trying to scam you so much as they want to try out a new kind of cut of meat instead of those same old boring primal cuts.

Creative butchery, as this is called, means there are quite a few new cuts of meat you may have never seen but still want to try out. Ask your butcher if they have any new ideas, which might include interesting new trends like oyster steak, Denver steak, and the bavette, essentially a thicker and more tender version of flank steak.