Here's What Food Coloring Is Really Made Of

In 2012, Starbucks received some backlash from the vegan and vegetarian communities for their Strawberry Frappuccinos. The issue specifically revolved around the red dye the company switched to after the resurgence of fear over the possible side effects of artificial coloring, as reported by CBS News. The Center for Science in the Public Interest's message to the FDA to ban artificial coloring cites a link with behavioral problems. This time, however, the outcry was due to the discovery that the dye's source was the crushed remains of the cochineal, an insect traditionally used to dye in Peru (via Live Science). "Our point is, vegans are drinking this and it's not vegan," Daelyn Fortney, co-founder of thisdishisvegetarian.com, explained. Obviously, that's right. Even though Howard Schulz exasperatedly pointed out that the dye appears everywhere, from candies to ketchup to lipstick, Starbucks switched to another natural dye.

Besides how it forces us to consider the ingredients that color our foodstuffs, the most interesting aspect of the Starbucks cochineal kerfuffle is the tension surrounding what constitutes an acceptable food dye. Live Science ran a short piece on the disappearance of red M&M's between 1976 and 1987. The reason was that the FDA found that the food coloring Red No.2 caused tumors in female rats, though its damages to humans remained unproven. So, they banned the dye and even though red M&M's don't have that specific food coloring, they were pulled for a while to save the company from public hysteria.

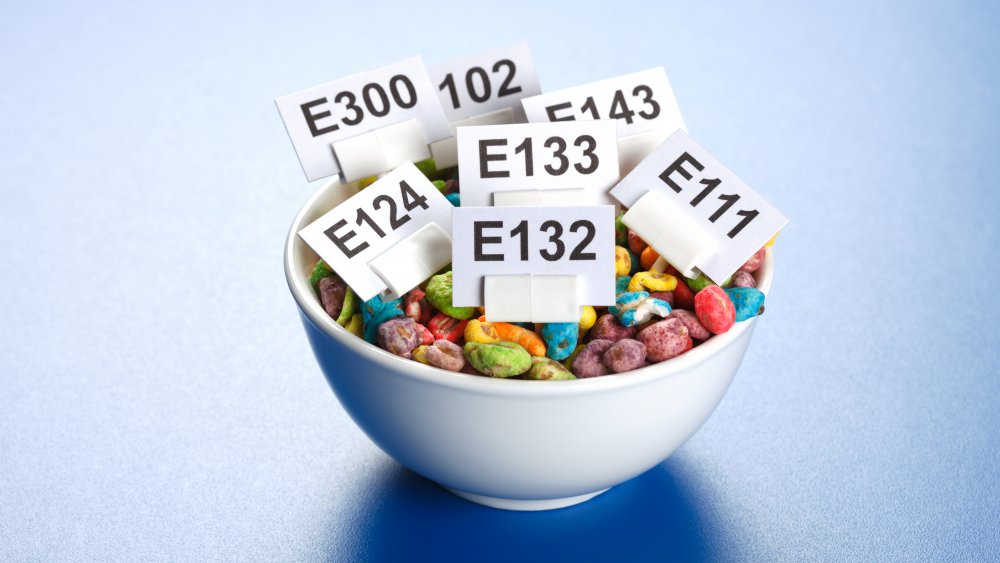

Naturally artificial

A lot of the discourse around the use of artificial or natural dyes is muddied by how we conceive the terms. Culinary Lore struggles to make this point in a 2015 dive into the differences between natural and artificial colorings. When the average person says "natural," they broadly mean anything that could be derived from nature, like caramel which we make from cooked sugars and use to give Coca-Cola that unnaturally rich color. However, this cooking process actually makes caramel an artificial coloring because even though its ingredients may be found in nature, nature did not naturally make them into caramel. In fact, a New York Times recipe for caramel lists the ingredients as brown sugar and water.

After bringing up this point, Culinary Lore leans heavily into impressing a new category: synthetic coloring, by which they mean what people imagine when they say artificial coloring – labs and chemicals. And, continuing their flip of the received "natural vs organic" understanding, they point out that the FDA has a list of naturally occurring color additives that aren't authorized, which includes saffron, charcoal, and cudbear, a purple dye derived from lichens. Cochineal must appear as a listed ingredient because, as Live Science notes, several people developed allergic reactions to it.

For those looking for easy ways to produce natural dyes, Bon Appetit has recipes for turning turmeric into a yellow coloring and simmering beets to produce a red dye – no insects for those who cannot abide them.

An antidote to the poison

The FDA, however, has hesitated on acting upon the claimed link between hyperactivity and artificial colorings. In a 2016 piece for Slate, Shilpa Ravella walks the reader through the reasoning behind unnaturally lurid food. As a species, we evolved to judge foods based on their color – every cell in our being revolts at the idea of eating something colored a mingle of beige and grey. Companies tap into this by tinting their foods to appear fresh. However, these Red No. 40s and Yellow No.1s consistently promote defects in animals upon which they're tested. This has caused many other countries in the European Union to ban these substances. The FDA hasn't followed suit. After all, the colors help sell the products.

Atlas Obscura presents exactly why these colors are dangerous. Namely, after decades of coloring Halloween candies with coal tar – a thick liquid that is produced as a byproduct of coke fuel – and children developing sicknesses from it the FDA put its foot down. Today's colors aren't produced from coal tar but rather petroleum and crude oil. A huge improvement. However, a counter to these trends is underway. In late September, Food Dive noticed that Phytolon, an Israeli firm that experiments with plant-based food colorings, raised $4.1 million in their latest funding round. And, as of 2019, natural dyes make up 69 percent of the food coloring market.