The Untold Truth Of Lay's

Everyone knows Lay's. That bright yellow bag with its simple red circle is a vital piece of Americana. Even without the name emblazoned across the front along with the sliced potatoes and chips scattered around the packaging, you could recognize this shape and color combo anywhere. Lay's has become a staple snack for children and adults alike, served at parties or alongside sandwiches, the perfect bite when you're craving something salty. You can find the potato chips, available in a wealth of flavors and a range of textures, all across the globe, even if Lay's potato chips are known under a different name elsewhere.

However, while the classic Lay's bag may be unassuming in every way, there's a lot of history behind the brand, as well as a bit of controversy — some fairly recent. For everything you never knew that you needed to know about your favorite potato chip, here's the untold truth of Lay's.

Lay's founder was a college drop-out

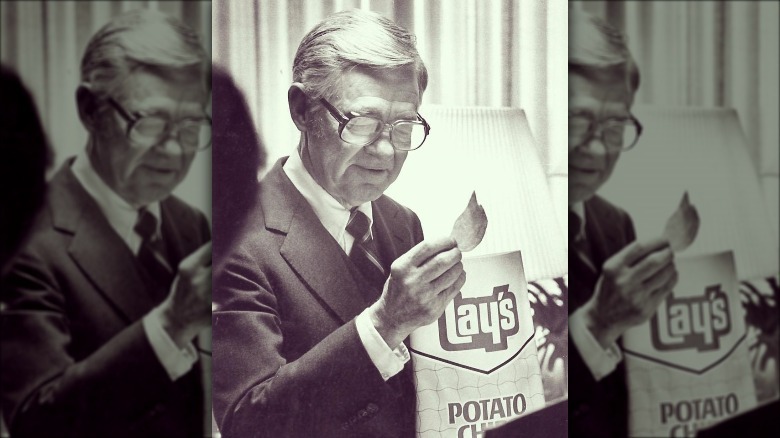

If you think it takes a college degree to create an international snack brand that's stood the test of time, think again. It turns out that Lay's founder Herman W. Lay was a college drop-out. Lay attended Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina, where he received an athletic scholarship, but he only remained in school for two years. After dropping out, he decided to channel his long-standing sales skills (as a young boy, he created and operated a soda stand, even hiring employees) by becoming a snack food distributor in Nashville. He raised funds and, after less than a decade, was able to purchase a snack food manufacturer in Atlanta, which he rechristened H.W. Lay & Company. There, he started turning out Lay's potato chips and quickly saw success throughout the South.

Lay did end up getting his college degree later in life, though. Furman University presented him with an honorary degree in the 1960s, and now the university offers the Lay Scholarship, giving recipients free tuition, room, and board in honor of Lay, who passed away in 1982 at the age of 73.

Lay's was the first national brand

Before Lay's, brands primarily stuck to their lanes, satisfied with regional prowess. However, Lay wasn't interested in only conquering the snack food world of the South, and so Lay's became the first-ever national brand when it merged with the Frito Company in 1961 to form Frito-Lay, Inc.

The Texas State Historical Association notes that the merger came shortly after H.W. Lay & Company acquired Rold Gold pretzels. At the time, H.W. Lay & Company was worth $45 million in annual sales, while the Frito Company was worth $60 million in annual sales. But after the two companies joined forces, Frito-Lay became an absolute juggernaut. By the 1980s, with worldwide distribution, more than 25,000 employees and 9,000 sales people, the company's combined annual sales reached $2 billion. A decade later, Frito-Lay was the largest snack food producer in the United States. According to Forbes, as of 2020, the brand is valued at $16.3 billion.

At first, Frito-Lay offered only four products

Right after the 1961 merger, the new Frito-Lay, Inc. only offered products from four brands, spread across its national distribution system. As Funding Universe details, the company, now worth $127 million in annual revenues and headquartered in Frito's home town of Dallas, offered products from both Fritos and Lay's, as well as Ruffles and Cheetos. With a newly merged leadership, the brand revamped its marketing efforts with the slogan "Betcha Can't Eat Just One" and new advertising spots on television. By 1965, the company had grown to $180 million in annual revenues.

Even after the merger, though, Herman Lay still showed his sales savvy in his new role as Frito-Lay CEO. In 1965 he sketched out a business deal on the back of a napkin while talking to then Pepsi-Cola CEO Don Kendall. The result of that meeting would be the creation of one of today's top international food and beverage companies.

Frito-Lay joined forced with Pepsi

In 1965, Frito-Lay merged with soda giant the Pepsi-Cola Company at the prompting of Herman Lay. Frito-Lay became its own, independent division of a new parent company that would be known as PepsiCo. For a time, the plan was to market Lay's potato chips and Pepsi together, as kind of a suggested dual snack. However, the Federal Trade Commission quickly decided that wasn't an approved marketing tactic and, in 1968, ruled that the two were not allowed to run joint ads.

Still, the merger brought other opportunities, such as expanding the number of products Frito-Lay offered, testing out and launching products such as Doritos in 1967, Funyuns in 1969, and Munchos potato chips in 1971 — all of which are still heavily recognizable today. Items like these helped the company stay relevant while facing new competition from brands like Pringles, which were considered revolutionary due to their molded shape.

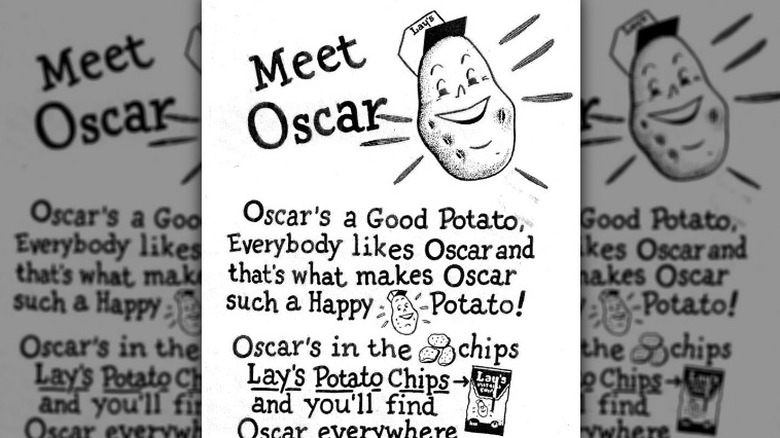

Lay's was the first snack food company to purchase TV advertising

As Insider reports, Lay's — when it was still known as H.W. Lay & Company — was the very first snack food producer to purchase television ads. The brand further notes that its spokesperson in these ads was an animated potato named Oscar who was introduced in 1944. Oscar the Happy Potato was described as "a good potato" and one that "everybody likes," which is what makes him so happy. The smiling, humanoid potato with a jaunty Lay's cap was then reported to be found emblazoned on every bag of Lay's potato chips, which, at that time, didn't feature the classic yellow hue with the red circle.

Even though the whole push to eat Oscar the Happy Potato is a little odd, the character proved to be popular, and you can even find him as a larger-than-life character (much like Tony the Tiger) on a 1950s Orange Bowl Parade float, where he was joined by several other potatoes with faces on the Lay's sponsored float.

The actor who played the Cowardly Lion was a spokesperson for Lay's

When Lay's upgraded from a smiling potato to a real-life human spokesperson in the late 1950s, they went with comedian Bert Lahr, best known as the Cowardly Lion in "The Wizard of Oz." According to son John Lahr, his father's television spots were so popular that while they aired, his prior credentials took a back seat and he became known pretty much exclusively as the Lay's Potato Chips guy.

"Never mind that Cole Porter had written shows for him, that he'd been the Cowardly Lion in the 'Wizard of Oz' and Estragon in the first American production of Samuel Beckett's 'Waiting for Godot': all these great performances were crowded out of the public imagination by the imperialism of the small screen owned at that point by nearly nine out of 10 American households," writes John in a 2011 New Yorker article. "To the new generation, Dad's fame didn't come from his exploits as a comedian onstage, but from his visibility as a guy saying, 'Betcha can't eat just one.'" Luckily for Bert Lahr, his legacy is now first and foremost tied to his iconic film role rather than his years as a potato chip spokesperson.

Lay's takes potatoes from field to fryer in 24 hours

If there's one thing that's key to Lay's success, it's not marketing or spokespeople (or spokes-potatoes) but the actual potatoes that go into each bag of chips. According to Keith Ballard, senior procurement director at Frito-Lay, he buys about 4 billion pounds of potatoes per year to make enough Lay's potato chips for both the United States and Canada. But getting those potatoes from field to factory to shelf is no easy task — especially when your goal is to get from field to fryer in 24 hours or less.

Lay's moves its potatoes from field to factory via truck or rail, depending on the farm location and potato quality. The company works with approximately 165 farms, and the longest route between farm and factory is from a North Dakota farm to a Georgia factory. Occasionally, if Lay's doesn't need the potatoes right away, the farmer will store the potatoes in a "sleeping" barn to await travel to their final destination at a more convenient time.

Lay's chips go from factory to store shelves in a few days

Once the potatoes reach the factory, it only takes about 20 minutes in total to unload the future Lay's chips from the truck, slice them, cook them, season them, and bag them, according to PepsiCo. The company attempts to keep its potatoes (and chips) as local as possible. A representative from Frito-Lay told ABC News in 2018, "We source these products locally and we produce them locally and get them straight into the store in a matter of days."

At the time, Frito-Lay said that it sourced most of its potatoes from Michigan and Wisconsin, though some of its most experienced farmers were located a little further south. One farming family told ABC News that they had been growing potatoes since 1928, and now, they send their potatoes just a few hours' drive to Georgia to be processed into Lay's potato chips. Another fun fact about the potato-to-package process: Each bag of Lay's potato chips contains the equivalent of approximately four to five potatoes.

In 2019, Lay's filed a lawsuit against farmers in India

As much fun as all the potato talk is, Lay's is pretty serious about its spuds — so serious, in fact, that PepsiCo attempted to sue farmers in India who were accused of growing the Lay's protected variety of potatoes, which are legally registered for exclusive use in Lay's products. However, PepsiCo did offer to settle with the farmers, telling them that they could either grow other, non-Lay's potatoes or they could join PepsiCo's "authorized cultivation program," in which the company provides seeds and purchases the potatoes from the farmers. The original lawsuit requested that each farmer — who individually own and farm just a few acres of land — pay PepsiCo nearly $150,000 in damages.

When PepsiCo was accused of essentially bullying the little guy, the company's spokesperson noted that "the company was compelled to take the judicial recourse as a last resort to safeguard the larger interest of thousands of farmers that are engaged with its collaborative potato farming program." However, after much pressure from unions and activities, PepsiCo dropped the lawsuit.

There are dozens of Lay's flavors and products

While Frito-Lay may have started out with just four products, today, you can find dozens of Lay's flavors and products available on store shelves around the world — and that's not even counting the products from the 28 other snack brands that fall under the Frito-Lay umbrella.

In addition to the traditional Lay's chips, which come in a bevy of flavors, there are also the Lay's lightly salted chips, Lay's dips, a line of kettle-cooked chips, Lay's Poppables, Wavy Lay's, Lay's Stax, and, most recently, Lay's Layers, which debuted in early 2022. The new chips, available in three-cheese and sour cream and onion flavors, are described as "multi-dimensional, one-of-a-kind potato bites with layers of delicious crispiness," according to Food Business News. However, despite the many popular Lay's potato chip flavors that are available, a bag of Lay's Classic potato chips is tough to beat — versatile, simple, yet full of flavor.

Lay's offers even more options internationally

If you look at Lay's international offerings, you'll find even more flavor options, as well as Lay's chips sold under a variety of different names. In the United Kingdom, for example, Lay's chips bags still sport that recognizable yellow sun with the red banner, but the name across that red banner isn't Lay's — it's Walkers. In Egypt, Lays' are Chipsy; in Israel, Tapuchips; and in Mexico, Sabritas. Different flavors range from a crab-flavored chip available in Greece, to a shrimp and garlic-flavored chip available in Spain. Seafood flavors are pretty popular elsewhere in the world, too, as there's a hot chili squid variety available in Thailand and spicy crayfish and fried crab flavors offered in China.

Lay's must have realized the appeal these seemingly off-the-wall flavors (at least to American palates) have to those who can't get their hands on them in the United States, because, starting in 2012, PepsiCo launched its Do Us a Flavor campaign, wherein it crowdsourced new flavor ideas and then asked America to vote on those that were actually made, making unique, never-before-seen flavors like Cheesy Garlic Bread and Chicken & Waffles available in stores.

Soil from NFL stadiums was used for a limited edition Lay's chip

The company's latest innovation is Lay's Golden Grounds. These chips are basically made the exact same way as normal Lay's original potato chips, but with an interesting twist. For the potatoes that will be used to make these chips, Lay's is taking dirt from NFL stadiums, adding that dirt to potato fields in Texas, and then giving fans the opportunity to say they've eaten a potato chip made from NFL dirt.

Unfortunately, it's going to be a little difficult to get your hands on these limited-editing bags. The chips are going to be distributed through a Twitter sweepstakes that ended Jan. 25, 2022. Entrants were required to post about their favorite NFL teams and also follow the Lay's Twitter account. Lay's plans to give away 5,800 bags of the Golden Grounds chips. It should be noted that the special chips did not recognize every single team in the NFL; the Browns, Bengals, and Broncos apparently did not contribute their dirt to the cause.

Lay's aims to become eco-friendly by 2025

You could probably guess that it takes a while for your Lay's potato chip bag to break down in a landfill. In 2019, United Kingdom publication Eastern Daily Press reported the discovery of a buried 1999 Walkers chips bag which had hardly decomposed over that decade.

Thankfully, Lay's is attempting to do something about the issue. The brand pledged to design 100% of its packaging as recyclable, compostable, biodegradable, or reusable by 2025. This pledge goes hand in hand with some of its other sustainability efforts, such as its goals to cut carbon emissions by more than 40% by 2030 and to achieve net-zero emissions by 2040.

Unfortunately, this isn't the first time Lay's has tried something like this and failed. In 2010, Frito-Lay unveiled a 100% compostable chip bag for its SunChips line, but quickly pulled the new packaging after sales declined by more than 10%, likely due to complaints that the bag was too loud.

Lay's hasn't made it through the pandemic without its controversies

Like many large corporations, PepsiCo and Lay's have earned some negative press during the pandemic — and if you're not familiar with the labor issues at Frito-Lay plants, it's time you got acquainted. In mid-2021, as CBS reports, hundreds of laborers at a Frito-Lay factory in Kansas picketed for nearly three weeks in response to excessive working conditions.

As demand for Frito-Lay products went up during the pandemic, so did the number of hours employees were forced to work, with many experiencing 12-hour shifts, mandatory overtime, 84-hour work weeks, and no days off. The company offered employees a 2% wage hike and a 60-hour-per-week working limit, which the employees denied. As a result of the strike, the workers secured a 4% wage hike and the guarantee of one day off each week and no more "squeeze shifts," which require employees to work 12 hours, be off eight hours, then come in to work another 12 hours.