Myths About Absinthe You Always Believed

Absinthe has delighted the masses for centuries with its alluring hues and herbal flavor. Its nickname, "The Green Fairy," comes from the French "la fée verte," which was affectionately given to describe the potent and beautifully green beverage. The herbal drink is composed predominantly of wormwood, anise, and fennel. The anise is what typically gives the drink its deep green color, which turns milky when water and sugar are added, creating what is called a louche.

With its lengthy history, absinthe has been a favorite drink of artists such as Pablo Picasso, Ernest Hemmingway, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. The drink even makes a prominent appearance in Baz Luhrmann's film "Moulin Rouge!" with the green fairy interacting with a fictionalized version of Toulouse-Lautrec.

Despite its raging popularity, the drink disappeared after it was banned for decades in several countries, including the United States. Today, despite its return, absinthe is shrouded in myth and misinformation. We are here to demystify this mysterious drink and help all those who are absinthe-curious find their way. Remember, just because a rumor has been around for years does not make it true.

Absinthe is hallucinogenic

Perhaps the greatest myth about absinthe is that it is hallucinogenic. Like all endearing misconceptions, this one has a grain of truth to it. One of the key ingredients in absinthe is wormwood. Distillation of wormwood releases a compound called thujone. There is some thought that thujone might have some hallucinogenic properties. Others, though, say that the effects of thujone, while psychoactive, are not necessarily hallucinogenic. Either way, there is one big caveat. There is not enough thujone in absinthe to cause hallucinations. The maximum amount of thujone allowed in absinthe under EU law is no more than 35 milligrams per liter. In the United States, the limit is just 10 milligrams per liter, which is such a tiny amount that absinthe is considered to be thujone-free.

Let's do some quick math. Assuming a 1.5-ounce pour of absinthe per drink, one liter of absinthe yields roughly 22 drinks. That means, at most, each shot of absinthe contains 1.5 milligrams of thujone under the EU. But with absinthe having an alcohol level of up to 150 proof, people are going to get very drunk before they consume enough thujone for it to have any sort of effect. Sorry, but the green fairy will not be visiting you after your drink.

If any hallucinations did happen from absinthe back in the early days, it was more likely due to poor standards and the addition of harmful ingredients to mask that poor quality rather than the thujone.

Absinthe is toxic

While we are on the subject of absinthe's supposed health risks, let's tackle the other big myth that claims absinthe is toxic. This lore has also been spread far and wide, but we are happy to inform you this is false. Or at least, it is no more toxic than any other alcoholic beverage.

Once again, this particular myth stems from a grain of truth, and once again, wormwood is the culprit. In large amounts, wormwood is considered toxic. However, toxic levels for mice are about 45 milligrams per liter, which, given the current levels of thujone in absinthe, are just not enough to harm a person (people are much larger than mice). You would be dead from alcohol poisoning before consuming enough thujone in absinthe to hurt you.

These days, you can buy wormwood supplements, teas, and other products. According to Healthline, many of those items don't fall under government regulation, so their thujone levels might be higher. We are not medical experts and are not advising anyone to purchase them. But it is clear that absinthe itself is not toxic with the inclusion of wormwood.

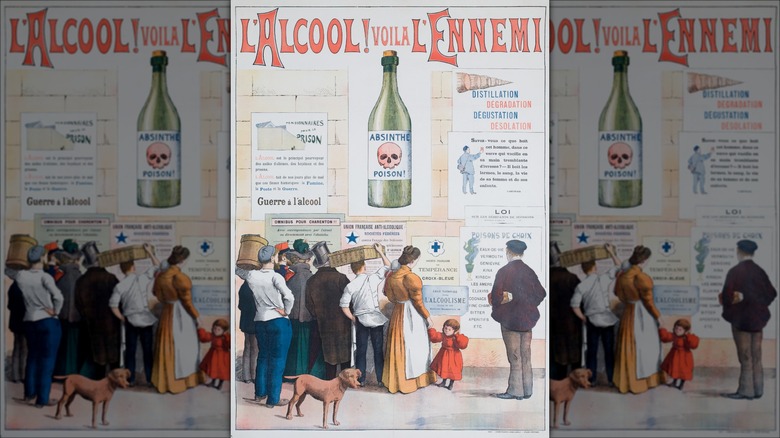

Absinthe was banned in Europe over its hallucinogenic properties

At the height of absinthe's popularity, the drink began to get banned throughout Europe and its colonies. Starting in 1898 with the Republic of Congo, these prohibitions spread through countries over the years: Belgium in 1905; Switzerland and the Netherlands in 1910; France in 1914; and Italy in 1932. It is commonly thought the reason for such bans was the supposed hallucinogenic properties of absinthe, but the truth goes much further. As we already know, absinthe is not hallucinogenic.

But during the early 1900s, absinthe became the scapegoat of poor and violent behavior as well as some ailments, including epilepsy. The drink was often unfairly blamed for Vincent Van Gogh's various mental health issues, including cutting off part of his ear. A few violent incidents of drunken men murdering their families were also linked to absinthe. It did not matter that they were known alcoholics.

The call for the bans was pushed further, not just by politicians and citizens concerned with society's degradation, but also by strategic lobbying from the French winemaking association. French wine was in a rough spot. The vineyards had been attacked by phylloxera, a destructive pest, and people's tastes for alcohol were leaning more toward absinthe. Winemakers were not happy about this, and to boost their own industry, they used their resources to further push for absinthe bans, which were ultimately successful. In the end, these European bans were not about hallucinations at all, but political strategy.

Real absinthe is banned in the United States

Now, this brings us to one of the longest-lasting bans, the one in the United States. Absinthe was initially banned in the United States in 1912. Prohibition, the ban on alcohol in the United States, went into effect in 1920 and was repealed in 1933. However, absinthe remained off-limits.

In 1988 the European Union lifted the ban on the drink by limiting the thujone levels to no more than 35 milligrams per liter. Interestingly, France maintained a ban on the name absinthe until 2011 despite being a prominent producer of the drink. Its alcohol was instead labeled as "a spirit made from extracts of the absinthe plant," according to the BBC.

The United States finally lifted the ban on absinthe in 2007 with the stipulation that thujone levels remain under 10 milligrams per liter. This is actually considered a "thujone free" level, according to a government circular for the industry. Now, some believe that because of these restrictions, American absinthe is not "real" absinthe, but this is false. Many American absinthes are made using traditional recipes and contain the three necessary ingredients to make it absinthe: fennel, anise, and wormwood.

Modern absinthe is different from classic absinthe

Despite the use of traditional recipes and distilling methods, there is still this idea that modern absinthe is different and somehow inferior to absinthe created before the bans. This is likely a case of romanticized history. Let's remember that while there was some excellent absinthe being made before the ban, there were also low-quality and toxic ones aplenty.

The main argument against the quality of modern absinthe is its thujone level. Current restrictions limit thujone to 10 milligrams per liter in the United States and up to 35 milligrams per liter in Europe. For a long time, there was little chemical evidence as to how high the levels were in absinthe before it was banned. There was a lot of speculation, with some estimating thujone levels as high as 260 milligrams per liter.

An analysis published in 2008 in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry of pre-ban bottles has proven those estimates to be wild exaggerations. Thirteen samples of absinthe that were dated before 1915 showed levels of thujone to be from 0.5 milligrams per liter to 48.3 milligrams per liter. The average was 25.4 milligrams per liter, which was actually slightly lower than the modern average of 26.9 milligrams per liter. Both pre and post-ban bottles offer a range of thujone levels, and there is no notable discrepancy between the two. It is definitely time to stop looking upon pre-ban absinthe with rose-colored glasses.

All absinthe is green

Absinthe is often thought to be solely a green liquor. With a name like The Green Fairy, the drink can be difficult to separate from its signature color to the point that many people just assume that all absinthe is green. The truth, though, is there is actually a range in absinthe colors. While the most popular absinthe is green, there are a host of other varieties.

Blanche absinthe is clear. In fact, all absinthe starts as blanche absinthe after initially being distilled. To get the green color, absinthe goes through a second phase where it is steeped with green herbs such as green anise, which releases chlorophyll and produces that distinctive color. Blanche absinthe is not steeped, which gives it a less herby flavor. Blanche absinthe gained popularity with Swiss bootleggers during the bans because it was easier to disguise than its green counterpart.

Since it is in the second phase of absinthe-making that the green hue is added, it is not surprising that some distillers have experimented with the color. Lawrenceville Distilling Company in Pennsylvania, for example, produces a red or "rouge" absinthe using a rare pre-ban recipe, which includes hibiscus to get its red color.

All absinthe tastes the same

With so many different colors of absinthe, it is no surprise that there is a range in flavors as well. Clear absinthe offers the most licorice flavor, as it is made with the three main ingredients: wormwood, anise, and fennel. Anise and fennel both offer a licorice flavor. Once you start adding in more herbs, though, the taste can change. Green absinthe tends to be herby, whereas red absinthe tends to be more of a floral spirit. Even within green absinthes, though, there is a range in flavor, and it is not just licorice, which itself is a separate plant from anise and fennel.

Recipes for absinthe vary by region and distiller. Often, French absinthe tends to be more herby, whereas Swiss versions can have a deeper fennel flavor. Czech or Bohemian absinthe will often have a light hand with the anise. Additional herbs are often used beyond the core three to provide new flavors. These herbs will vary based on who is making them and offer a slightly different bouquet and taste than others. If you have had one absinthe and did not like it, do not write off all absinthe; try a different producer or style to see if one might fit your tastes better.

You need special equipment to serve absinthe

The traditional way to serve absinthe is somewhat labor-intensive and calls for special equipment. For the home drinker, this can be a turn-off. It is easy to assume you need this equipment in order to properly serve absinthe, but that is not true.

There is also a ritual that some use when serving absinthe, which one could argue is part of its appeal. You start with a Pontarlier absinthe glass. This is a fluted glass that has a noticeable section to measure the absinthe. Then you have either an absinthe fountain or absinthe brouilleur filled with cold water that drips slowly into the glass of absinthe. Then you need an absinthe spoon, which is long, flat, and thin with slots in it. The spoon holds a sugar cube that sits under the dripping water and slowly dissolves into the absinthe, eventually producing a louche, which is the cloudy concoction made from absinthe, cold water, and sugar.

This is all very well and good, but really, that is a lot of investment for single-use items. If you really want absinthe, you do not need any of that stuff. Just get a glass, a bottle of absinthe, cold water, and some sugar to taste. Mix the cold water and absinthe directly in the glass, and then add either simple syrup or sugar. Stir until dissolved. You will still get the louche effect without having to buy a thing.

There is only one way to serve absinthe

There is a popular misconception that there is only one way to drink absinthe: the traditional drip method. But this is simply not the case. As stated above, it is easy to enjoy absinthe without a sugar cube. There are also variations that use a sugar cube soaked in absinthe and lit on fire. This is a controversial method that is more common with Czech absinthe. Many claim that it will ruin the absinthe or that it is primarily used to cover low-quality absinthe – alcohol is also highly flammable, so this carries some risk. Still, if you like it, do what makes you happy. Some even forgo sugar altogether, though the sugar does help to mask the bitterness of absinthe.

Now, if the absinthe drip is not your thing, there are also a host of cocktails that utilize absinthe. A Corpse Reviver No. 2, for example, uses an absinthe rinse on a glass to give just a hint of flavor to the cocktail, as does a classic Sazerac. Author Ernest Hemingway created a cocktail that is simply absinthe mixed with champagne, appropriately titled Death in the Afternoon.

The one way we do not recommend absinthe, though, is drinking it straight. Absinthe can be as high as 150 proof. It is incredibly strong in both alcohol and flavor. Drinking absinthe neat or doing shots might not be enjoyable or even advisable.

Absinthe only comes from Europe

This is one of those myths that probably got its start because people typically associate the drink with Europe. Images of absinthe throughout history have come from artists across Europe. But the truth is, unlike other alcoholic beverages such as bourbon, which must come from the United States, and tequila, which must come from specific areas in Mexico, there is no such restriction on absinthe.

In fact, since the repeal of the law banning absinthe in the United States, many American distilleries have begun to make their own liquor, such as Lawrenceville Distilling Company, which makes an absinthe using an 1855 recipe, and Great Lakes Distillery, which makes two different kinds of absinthe based on old recipes.

Now, where some of the confusion may come in is that there are certain designations of absinthe that are legally defined. For example, absinthe from Pontarlier, France, has always had an excellent reputation. But as of 2019, the label "absinthe de Pontarlier" can only come from that region. This is similar to the rules about champagne only coming from the Champagne region. Sparkling wine and absinthe can both be made elsewhere, but to receive this valuable naming, the two must be produced in the respective areas.

Absinthe is a French drink

Absinthe is often associated with France. It was hugely popular in the country during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Pontarlier, France, is still known as a premier absinthe region, and Henri-Louis Pernod of Pernod is often credited with creating the first commercial absinthe distillery in France.

The spirit undoubtedly has strong ties to France, but absinthe was actually created in Switzerland. It is said to come from the canton of Neuchâtel, which shares a border with France, which may be part of why it became so popular and synonymous with the French. While the exact origins of the first absinthe are unknown, it is thought to have been created by Pierre Ordinaire, a French exile living in Switzerland. Others suggest it started in the 1700s with Mère Henriod, who was Ordinaire's housekeeper and who made and sold the drink after Ordinaire's death. Originally absinthe was meant as a way to use wormwood to treat stomach issues, but obviously, it took off in a totally different direction.

Amazingly, even as Switzerland was the birthplace of the drink, that country was one of the early ones to ban it as well. It was prohibited in the country from 1910 until 2005, not that this stopped some of the Swiss from continuing to produce the drink. Distillers did their work in secret until the ban was lifted, and they were finally able to produce freely again.

Absinthe makes you more creative

Absinthe has long been credited for unlocking creativity. Artists such as Vincent Van Gogh and Pablo Picasso created works inspired by the drink. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was such a fan that he had a hollowed-out cane filled with it. Oscar Wilde reportedly described absinthe in this way: "After the first glass, you see things as you wish they were. After the second, you see them as they are not. Finally, you see things as they really are, and that is the most horrible thing in the world." From this quote, it is easy to see how the idea of absinthe's mind-opening properties and as a way of promoting creativity came about.

We are sorry to disappoint those who were hoping for something greater, but absinthe does not have any magical powers. Absinthe also does not contain enough thujone to act as a hallucinogenic. It is, though, an incredibly potent liquor. But that is not necessarily going to give a boost to creativity. Researchers from Essex University and Berlin's Humboldt University did an analysis and found no positive connection between drugs and alcohol and creativity, despite what some artists may think, per a report of their 2023 study in The Guardian. Absinthe may be enjoyed by many artists, but it is not responsible for their success.