The Untold Truth Of Pho

Who can resist the pleasures of a perfectly prepared bowl of pho? Once the gently-spiced aroma of the broth enters your nostrils and you see the piles of beef or chicken and flat rice noodles, it's hard not to start salivating. All the toppings on the side let you customize the flavor exactly the way you like it, and the spices in the broth have been said to have medicinal properties, or at least take the edge off of a nasty hangover (via Medium).

But how did pho become pho? Although it's many people's introduction to Vietnamese cuisine, pho didn't exist for most of the country's history, and it shows numerous foreign influences in its ingredients and cooking techniques. The story of pho is a fascinating, at times depressing, chronicle of how Vietnamese cooks adapted to colonialism, war, and scarcity. Like the broth itself, pho's history combines diverse components from many parts of the world to produce something greater than the sum of its parts.

The numbers in your local pho restaurant's name have an important meaning

Have you ever noticed how a ton of pho places have number-based names? We've seen Pho 888, Pho 67, Pho 75, and more. It's the most common pho restaurant naming convention besides the ubiquitous (and obnoxious) pho-based puns. Restaurateurs take note: the world doesn't need any more Pho Shizzles or Pho King Deliciouses. The number tradition is so commonplace that it's even been lampooned by comedian Ali Wong (via 99 Percent Invisible). Although the numbers in pho joint names might seem random to the average Western observer, for Vietnamese and Vietnamese-American people they are quite meaningful. Some numbers, for example, represents monetary good fortune and business success in some Asian cultures (via Serious Eats).

If the number isn't a traditionally lucky number, then it probably refers to an important date either in Vietnam's history or the family history of the restaurant's proprietors. The number 54 shows up frequently because that was the year Vietnam split into two countries, North and South. Another popular number is 75, as that was when Saigon fell to North Vietnamese forces.

Pho started out as a very basic dish

Pho began in North Vietnam as a simple dish of beef broth and rice noodles (via Asian Inspirations). As it spread throughout the country, cooks adapted it to their own regional styles. The simple Pho Bac of the North became complex Pho Nam in the South, which is the style of pho you're most likely to get in North America. The two styles of pho are still distinct from each other today. Northern pho emphasizes the pure taste of its meat broth accentuated with simple toppings like sliced beef and green onions. Southern pho is an exercise in controlled chaos, with a sweeter, more heavily-seasoned broth, a wide variety of meats to choose from, fresh herbs, lime, and hoisin sauce all contributing to its distinctive flavor.

The question of which style is the ultimate pho still divides North and South Vietnam. Tuoi Tre News reports that one Northerner's takedown of Pho Nam in Ho Chi Minh City caused a firestorm on social media, with partisans from both regions arguing for the superiority of the pho they grew up with. The most levelheaded take on the issue came from Phong Lan Phan Ngoc, who had spent time in both regions of Vietnam: "There is no objectively better pho as northern and southern pho tap into your food senses differently."

The Vietnam War brought pho to South Vietnam and the U.S.

As we alluded to earlier in this article, the 1954 partitioning of Vietnam into two countries that led to the Vietnam War also expanded pho's range beyond its North Vietnamese home turf. The 99 Percent Invisible podcast explains that under the partition the North became communist while the South installed a capitalist government. Before the border closed, citizens had a few months to relocate to the part of the country with their preferred economic system.

During this time, up to 1 million North Vietnamese people resettled in South Vietnam, many of them in the city of Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City). These migrants made pho that suited Southern tastes and ingredients, adding more herbs and chili. When the North Vietnamese communist forces took control of South Vietnam, many Southerners feared reprisal because of their collaboration with capitalists and Americans. They fled the country in droves, opening pho restaurants wherever they settled and turning the dish into a global sensation.

Pho was originally a street food

The exact origins of pho are mysterious, but the most popular story is that it began in a village called Van Cu in the rural Nam Dinh region of North Vietnam (via Viet World Kitchen). The village churned out many talented pho cooks, some of whom brought their local delicacy to Hanoi and opened businesses there. Nam Dinh still has its own distinct style of pho in which the beef is stir-fried with flavorings before being added to the soup (via BBC).

Although pho may have started in Nam Dinh, it first became popular on the streets of Hanoi sometime around the turn of the 20th century. At the time, wandering noodle vendors were a common sight in the city, especially in working-class neighborhoods. A woodcut from around this time shows a typical pho seller of the period balancing a wooden staff across his shoulders with a cauldron of broth hanging from one side and boxes full of noodles hanging from the other.

The first people in Hanoi to embrace pho were the dockworkers and laborers who worked in the city's shipping industry and needed a quick, nourishing, and convenient meal. Vietnam Travel says that pho is still a popular street food in Hanoi today, although the roaming merchants have been replaced with stationary stalls.

The name comes from a French word (maybe)

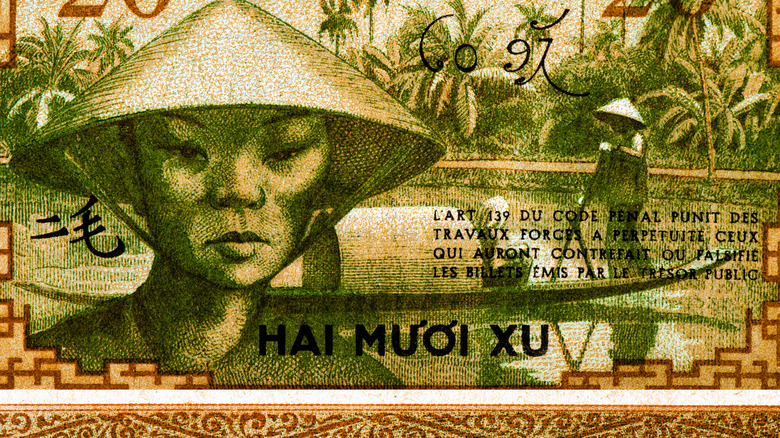

According to Bliss Saigon, beef wasn't a big part of the Vietnamese diet until the French occupied the country in the 1880s, ruling it as French Indochina. Wealthy French colonists began raising cattle for beef production, but they tended to eat steak and other prime cuts, leaving the bones and trimmings for local cooks and butchers to use. Vietnamese innovators began using these castoffs to make beef broth, serving it with rice noodles that were already popular at the time. One theory suggests that they called this creation pho after the French pot-au-feu, a kind of beef stew. Although you wouldn't know this from the way they're spelled, pho and feu are pronounced almost identically.

The French connection is the most commonly cited explanation for pho's name, but not everyone is convinced. Pot-au-feu has almost nothing in common with pho other than containing beef, so it might be a coincidence that the two names sound so similar. Pho expert Andrea Nguyen argues that it's much more likely that pho evolved from phan, the Cantonese name for the type of rice noodles in the soup.

There's a big debate about sriracha and hoisin in the broth

In 2016, Bon Appétit faced a huge backlash because of racial insensitivity in their video department (no, we're not talking about the thing you think we are). The publisher angered a huge swathe of the Vietnamese-American community by choosing to interview Philadelphia-based chef Tyler Akin, a white man, about the "correct" way to eat pho (via Mic).

Critics lambasted the decision, pointing out that Philadelphia has numerous excellent pho restaurants owned by people of Vietnamese descent that Bon Appétit could have asked for pho eating tips. Others took umbrage at Akin's specific suggestions, particularly his declaration that you shouldn't put hoisin and sriracha directly in the broth.

One Facebook commenter said, "I'm Vietnamese and I always put hoisin or sriracha into my pho." Andrea Nguyen told Mic that she objected to the idea that there is one correct way to eat pho, saying "It is, at its core, this 'have it your way' soup." A Vietnamese-American writer on Medium echoed Nguyen's position, arguing that the extra kick from hoisin and sriracha may be necessary to correct for the blandness of the broth in some Americanized pho restaurants. As we've seen, pho is a chameleon that changes depending on what region it's served in, so declaring that there is only one proper type of pho is reductive and simplistic.

Pho is a breakfast food in Vietnam

One strange thing about pho's popularity in South Vietnam is that the region has a tropical climate with double-digit humidity and temperatures that can climb up to the 100s. That's not really the type of weather that makes us crave a steaming bowl of beef noodle soup. The thing is, most Vietnamese people don't eat pho for lunch and dinner like Americans do. Instead, they eat it early in the morning while it's still relatively cool outside. Eater says that pho cooks in Vietnam typically start their broth in the middle of the night so they can open up by 6 a.m. Popular stalls sell out by 9 or 10 in the morning. Diners cherish their morning pho, prizing it as a revitalizing start to the day after a long night. In present times, pho has moved beyond its breakfast roots, and now you can find pho vendors open at all times of day in the big cities.

It's based on an earlier dish called xáo trâu

Before the French popularized beef consumption in Vietnam, water buffalo was the most popular red meat in the country (via Saigon Food Tour). Buffaloes were used for farm labor like plowing fields and pulling carts, and they were slaughtered for food after they could no longer work. The classic way to prepare water buffalo was a simple mixture of boiled meat, broth, and rice vermicelli called xáo trâu. Xáo trâu was a peasant dish, offering hearty sustenance to farmers and laborers in the chilly northern parts of the country. Once Vietnamese cooks started swapping beef for water buffalo, they traded out the vermicelli for a flat rice noodle that traditionally served as the base for a crab soup called bánh đa cua (via BBC).

Although modern pho basically replaced the earlier xáo trâu in the Vietnamese diet, water buffalo meat is still enjoyed today. If you're curious about it and live somewhere where you can buy buffalo from a butcher, this recipe from Ameovat for stir-fried buffalo with water spinach is a good example of how Vietnamese cooks prepare the ingredient in modern times.

Chinese culture also played a role in creating pho

The French may have introduced Vietnamese cooks to beef, but what about the noodles? An article published by the Cereals and Grains Association says that rice noodles were invented in China during the Qin Dynasty over 2000 years ago. Although the specific circumstances of their invention are lost to time, one theory suggests that when wheat-eating Northern Chinese armies invaded rice-eating Southern China, they invented a way to transform rice into the noodles they were accustomed to eating. Rice noodles became a staple in Southern China, including the Yunnan province that borders Vietnam.

During the early 20th century, Chinese laborers migrated to Hanoi looking for work in the shipping industry (via Greeley Tribune). They brought their traditional rice noodle soups with them, and many of the noodle vendors in the city at this time were of Chinese descent. It's likely that a large portion of both the cooks and diners at the earliest pho businesses were originally from China.

The broth in pho uses a lot of sweet spices

The exact composition of pho broth varies from cook to cook, with chefs closely guarding their secret recipes. Although each broth expresses the unique personality of its creator, most pho shares the same basic spice profile. Andrea Nguyen says that, like rice noodles, pho spices show a clear influence from Chinese cuisine. A comparison between the pho spices she lists and the components of Chinese five-spice powder shows how similar the two flavor profiles are (via Woks of Life).

Both use star anise, cloves, cinnamon, and fennel seed. You might notice that many of these spices are more commonly used in desserts in Western food, with cloves and cinnamon showing up in pumpkin pie spice. Pho amps up the sweet flavor of its spices by adding sugar and ginger to the broth as well (via Serious Eats). The balance between the sweetness of the sugar and spice and the savoriness of boiled beef bones makes pho the addictive treat it is.

Pho is a cultural appropriation battleground

Pho has a much shorter history than other Vietnamese dishes, with written records only going back a little over 100 years. It's also a product of colonialism and foreign influence on Vietnamese cuisine. Despite this, it's an important part of Vietnamese identity often described as Vietnam's national dish (via BBC). While the popularity of pho in Western culture has been a boon to restaurant owners of Vietnamese descent and increased the visibility of the country's cuisine on the global stage, it has also provided an opportunity for non-Vietnamese cooks to co-opt and adapt food traditions in a way that some find offensive and harmful.

This dynamic came to a head when Tieghan Gerard, a white cook who runs a blog called Half Baked Harvest, posted a recipe she called "Weeknight ginger pho ga (Vietnamese chicken soup)" in early 2021 (via Today). The recipe inspired many negative reactions, as it had very little in common with traditional Vietnamese chicken pho. Critics felt that Gerard carelessly exploited the popularity of pho without bothering to do the research necessary to ground her recipe in the cooking tradition she was borrowing from. The backlash inspired wider discourse on when, if ever, it's appropriate for non-Asian cooks to represent themselves as authorities on Asian cuisine.

The biggest pho in the world weighs over 13 pounds

Pho started life as a quick way for laborers to get a lot of food in their belly, and one restaurant in Seattle is taking pho's generous portions to the extreme. According to Narcity, Dong Thap Noodles claims it serves "the world's largest pho" (there's no word from Guinness on the veracity of this claim). This monstrous bowl of soup contains three liters of broth, three pounds of noodles, and three pounds of a mixture of tripe, tendon, brisket, flank, steak, and meatballs, coming in at over 13 pounds in total (via Seattle Refined). The restaurant recommends eating it with five friends. You used to be able to order it yourself for the opportunity to win $100 if you finished the whole bowl, but Dong Thap no longer lets people do this eating challenge. Although the pho is huge, the restaurant is tiny, seating only a maximum of 35 people. Since the giant bowl of pho is now internet-famous, you might have to wait a while to score a seat for lunch!

The most luxurious pho costs $79

Dong Thap's giant pho costs $77, which puts it two dollars shy of the world's most luxurious pho: the Phozilla from San Mateo, California's Gao Viet Kitchen. What Phozilla lacks in size, it more than makes up for with expensive, fancy ingredients. The restaurant's owner, Viet Nguyen, told Eater that he decided to create this ostentatious bowl of soup after seeing other high-priced foods gain attention on The Food Network and Instagram. His own bid for virality is certainly a head-turner. It's topped with filet mignon, brisket, bone marrow, an entire beef rib, braised oxtail, and the piece de resistance: a steamed whole Maine lobster.

With all those luxury ingredients, Nguyen could probably set Phozilla's price significantly higher, but he says "I just do not have the heart to charge people $100 so instead I just charge $79." Although Phozilla is kind of a joke, serious technique goes into making it. The broth is simmered for more than a day and is enriched with bone marrow to give it an exceptionally deep flavor. If you want to try it yourself, bring a friend, because only two people have ever finished it by themselves.

The Tet Offensive was planned in a pho restaurant

The Tet Offensive was one of the most pivotal turning points in the Vietnam War. It consisted of a series of strikes on strategic locations in the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon by North Vietnamese Viet Cong forces in 1968. The whole thing was planned in the upper room of Pho Binh, a restaurant in Saigon popular with American soldiers (via Roads and Kingdoms). U.S. troops had no idea that this little noodle shop was actually a Viet Cong front and that upstairs a secret organization called the City Rangers was formulating a strategy to attack the city. The Viet Cong asked Pho Binh chef-owner Ngo Van Toai to supply the North Vietnamese forces with food once the Tet Offensive began. When the South Vietnamese temporarily regained control of Saigon, they punished him with imprisonment and torture. Although he passed away in 2009, Pho Binh is still open today.