The Untold Truth Of Zima

Do you remember Zima? Few drinks have inspired such feverish interest for such a brief amount of time. During the brand's height, most American alcohol consumers tried the stuff, and its inventor Coors thought that Zima would change the face of the whole alcohol market. Its ads were an inescapable part of the '90s media landscape, and it was the subject of newspaper articles and TV shows. Then, seemingly overnight, people stopped buying Zima, and the American public watched in glee as the fad flopped and turned into an embarrassing failure.

Although the clear malt beverage didn't become a longstanding institution like Coors hoped it would, in many ways we are living in a world birthed by Zima. According to Statista, U.S. consumers bought hundreds of millions of dollars' worth of flavored malt beverages in 2020. The brand's innovative commercials also left an indelible mark on the history of advertising. Why did Zima fail to convince U.S. consumers to embrace malternatives when other brands saw success just a few years later? Read on to learn more about the rise and fall of Zima.

It was a part of the '90s clear craze

Released in 1993, Zima was very much a product of its time. It was part of the early 1980s/late '90s fad called the "Clear Craze." According to the marketing professionals at Dark Roast Media, this trend was built on concepts of purity pioneered by Ivory Soap in their advertisements from the late 1800s. Allison Venezio writes that making products clear signaled that they were free of artificial additives (whether that was actually true is another story). The trend was so pervasive that it expanded beyond household items, food, and beverages to electronic products like the Game Boy and the iMac.

The Clear Craze hit the beverage industry hard in the 1990s, with beverages like Clearly Canadian and TaB Clear hopping on the purity bandwagon. The most well-remembered relic of this period is Crystal Pepsi, an attempt to make a clear cola that debuted the same year as Zima. Several breweries introduced clear beers, with Miller Clear, Pabst Izen Klar, and Stroh's Clash joining Zima in this crowded sector (via Slate). Ultimately, many drinks from the Clear Craze period suffered from a focus on appearance over taste and swiftly lost popularity when the novelty wore off.

Zima was made by filtering the flavor out of low-quality beer

According to Ranker, Coors figured out that they could make a clear alcoholic beverage by removing the color and taste from their worst beer with activated charcoal. They added lemon-lime flavor to this bubbly, flavorless liquid to create Zima. Rival brewery Miller also used the charcoal filtration process to create their Zima competitor Miller Clear (via The Washington Post).

However, as Slate notes, the charcoal removed most of the beer-like qualities of the brew, leaving a beverage that tasted more like soda than beer once the flavorings were added. Coors decided that labeling Zima as "beer" would harm its chances with consumers, so it marketed the drink as a new category of a beverage called clear malt. In doing so, Coors paved the way for future, more successful malternatives like Mike's Hard, Smirnoff Ice, and Twisted Tea that aren't reminiscent of beer at all despite being made with the same ingredients.

It was an instant hit, but sales diminished quickly

Coors had high hopes for its new product and invested a ton of money into rolling it out nationwide. Bloomberg reports that the brewery spent $180 million on the brand's national launch in 1994. Ranker says that $38 million of that went to marketing, which initially paid off: In its first year of widespread availability, about 7 in 10 American drinkers tried Zima, and Coors sold over a million barrels of its new product (via Mental Floss). That was good for 1% of the entire American alcohol market, but the honeymoon didn't last long.

Sales dipped after that year and never again reached their 1994 height. Although the product wasn't the transformative hit Coors was hoping for, business wasn't as bad as Zima's notorious flop reputation would suggest. According to Slate, Coors sold over 600,000 barrels of a reformulated version of Zima in 2000. Since it was made with cheap ingredients and sold at a mark-up, Zima was profitable for Coors long after it fell out of the zeitgeist.

Coors marketed Zima to men, but it developed a feminine reputation

Although you'd think selling your product to only half the population would limit its overall appeal, Coors decided early on that they didn't want Zima to be for ladies. Zima's early marketing stressed that it was a manly product perfect for young men who wanted an alternative to beer (via Mental Floss). The conventional marketing wisdom of the time was that men wouldn't touch any product associated with women or femininity. Beverage consultant Tom Pirko told The Washington Post in 1993 that he worried that young men would decide that clear beer was "a sissy beer."

Apparently, the fragility of the American male knows no bounds, because Pirko's prediction came true. Coors was horrified to discover that women liked Zima much more than men did, and men avoided Zima for fear of having their masculinity challenged. The brewery eventually embraced women in its marketing strategy later in the brand's lifespan, but by then it was too late to save the struggling beverage (via Slate).

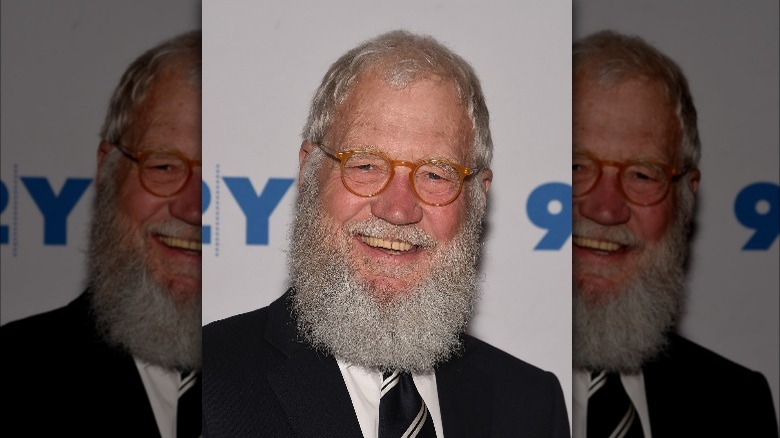

David Letterman helped turn Zima into a cultural joke

As if Coors didn't have enough on its plate trying to scrape the cooties off of Zima's brand when (gasp!) young women decided they enjoyed its lemon-lime kick, David Letterman gave the drink heaps of unwanted exposure by regularly incorporating it into his monologues. Per Miami New Times, some Zima executives thought that being mentioned in one of America's most popular late-night shows was welcome free publicity, while others thought that being the butt of nightly jokes could only hurt the brand's already-shaky reputation.

Early on, Coors played into the gag and gave the comedian free cases of Zima, but ad executive Scott Rabschnuck told the Miami New Times that he regretted adding fuel to the comedic fire. Letterman liked using Zima as a punchline in his Top Ten Lists, but he didn't have a particular grudge against the drink. If anything, the fact that his Zima bits worked indicated that the general public already thought the malternative was a worthy target for mockery.

Zima's taste was divisive

Why did Zima's sales go down so quickly after its first year? Why did most of America decide that the drink was somehow inherently hilarious? It ultimately came down to the flavor. While some people enjoyed it (it did continue to sell hundreds of thousands of barrels even after it slunk away from the limelight after all), a majority of the people who tasted it thought it was gross. This Reddit thread of people sharing their Zima memories is filled with unsparing critiques. One user described the taste as "scotch tape with lime," while another evoked the experience this way: "Allow a can of Mountain Dew to go flat. Mix with equal parts lemon juice and vodka." Sounds delicious!

Zima's flavor issues didn't come from a lack of effort on Coors' part. According to the Miami New Times, the brewery enlisted scientists from multiple disciplines to work for months developing the product and thoroughly tested it with focus groups before finalizing the formula. It performed well in the initial test markets where it was released in 1992. Nothing could have prepared the company for the negative reception Zima got once it went national. Apparently, nobody in the focus groups said that Zima tasted like "tonic water and antifreeze," "icky beer," or "flat Sprite," as the Miami New Times quotes some drinkers in 1995 as saying.

Zima's marketing left a bigger impression than the product

Coors poured a lot of money into marketing Zima when it first came out, spending approximately a third of their total ad budget on the product, equal to what they spent on their flagship Coors Light (via Miami New Times). As we've discussed, they wanted to project a masculine image, but they even more specifically wanted to target Gen-X consumers, who were young adults at the time. The generation that gifted us with slacker culture and Nirvana were the alternative cool kids of the '90s, and Coors thought they would be open to Zima's radical reinvention of beer.

You can clearly see Coors' strategy at work in Zima's first round of ads, which you can watch in this Metro collection. The pitchman is dressed in a Madison Avenue executive's version of a '90s hipster outfit, with a pork pie hat and a thrift store suit, and he quirkily swaps his s's for z's. The settings of the commercials reinforce the alternative vibe, dropping the pitchman into a metal concert, a backyard barbecue filled with pretentious people, and a smoky bar. Although these ads failed at their main job, making people like Zima, their surreal vibe and stylish aesthetics feel prescient. In subsequent years, many brands have used strange pitch-people with random quirks in ad campaigns, from Orbit Gum to Starburst to Old Spice.

After sales dipped, Coors reformulated Zima several times

Once it became clear (no pun intended) that no amount of marketing could make up for Zima's lackluster flavor, Coors scrambled to rectify the situation by messing with the drink's formula. The first attempt at course-correction was Zima Gold, which was amber-colored, boozier, and allegedly whiskey-flavored. It was a last-ditch effort by the boy-crazy brewery to make Zima seem manly, and it was discontinued less than six months after its release (via Slate).

After that, Coors decided to switch course, changing Zima's recipe to make it more soda-like and marketing it as a cool refresher for hot days. This approach was moderately successful and propped up the brand's sagging sales. Zima morphed yet again in 2004 to compete with its more famous little sibling Smirnoff Ice, rebranding as Zima XXX and pairing the extreme name with more assertive flavors and a higher ABV. On the eve of its retirement, it transformed one last time, switching to a low-alcohol, low-calorie formula that executives hoped would appeal to women, who had been some of the drink's most faithful customers throughout its run. Despite embracing Zima's real fanbase for the first time, this experiment didn't prevent the drink from getting axed in 2008.

It was popular with underage drinkers

Women weren't the only Zima fans that Coors was dismayed about. Teenagers also loved it, and its popularity with underage drinkers became a scandal. A Washington Post report from 1995 quoted several health officials who had concerns that the beverage could promote underage drinking because it tasted more like soda than beer and it didn't obviously look like alcohol (via Orlando Sentinel). Since Zima didn't have a strong alcoholic odor, teens and concerned parents thought that it might not show up on breathalyzer tests. This rumor was so widely-believed that Coors rebutted it in a letter to police departments and school districts stating the obvious fact that since Zima contained alcohol, it would trip a breathalyzer.

This reminiscence in Gothamist from Jen Carlson, who was a teenager in the '90s, attests to the popularity of Zima among high-schoolers from a first-hand perspective. She says that her peers made it taste even more like candy by dropping Jolly Ranchers in it. One poster in this Reddit discussion also mentions the Jolly Rancher trick, and another says it was popular to put a shot of fruit-flavored schnapps in each bottle. Sounds like a recipe for a hangover to us, but young people are able to tolerate sugary concoctions like Boone's Farm and wake up unscathed the next morning.

Changing tax laws and low sales killed off Zima in the U.S.

A cocktail of unrelated events combined to finally strike the death blow against Zima. For one, California, a very large market, sharply raised taxes on sweetened malt beverages in 2007. The OC Register reported that the state upped the excise on products like Zima, Smirnoff Ice, and Mike's Hard Lemonade from a mere 20 cents a gallon to a steep $3.30. The huge tax increase cut into Coors' profits from Zima, and it died soon after the law passed. The last call came in October 2008, when Coors announced it was ceasing production and would sell out its last remaining inventory by the end of the year. The company wrote in a letter to distributors that falling demand for malternatives was to blame (via Chicago Tribune).

Ironically for those who were concerned about Zima's association with underage drinking, the brewery encouraged retailers to replace Zima with Sparks, a caffeinated alcopop. Newsweek's tribute to Sparks, which was killed off later in 2008, says that teenage drinkers were big fans of this malt beverage too. It was a sort of proto-Four Loko, combining potent malt liquor with sugary flavors as well as caffeine, guarana, and ginseng. Zima looked positively meek in comparison.

Zima is still popular in Japan

While Zima constantly tried to reinvent itself in the U.S. and tested out new identities like a confused teenager, it stayed steady (and popular) in Japan (via The Daily Beast). Japanese drinking culture doesn't have a strong gender prejudice against choosing a fruit-flavored beverage over beer, and Zima is a popular choice among drinkers of both genders. Millions of cases are sold each year, and Zima is a common sight both in bars and in convenience store refrigerators.

As in the U.S., the drink was initially marketed heavily towards the young male demographic because they were the heaviest alcohol consumers. In an inversion of the drink's problems stateside, Zima began to be seen as too macho for women in Japan, who abandoned it in favor of competitors like Smirnoff Ice. In response to this, Coors put out a pink, cherry-flavored version of Zima in hopes of luring back some female drinkers, with moderate success.

Zima returned to the U.S. market temporarily in 2017

In the 2010s, everything from the '90s was cool again, and the wave of Clinton-era nostalgia was sure to reach Zima eventually. In 2017, just one year after its Clear Craze companion Crystal Pepsi was resurrected, MillerCoors announced Zima's limited-time-only comeback (via People and Business Insider). The relaunch leaned hard into '90s kitsch, throwing other period references like JNCO jeans and Troll dolls into the new Zima ads. The version of the product that hit shelves that year turned the clock back on all the rebrands, using similar bottles and lemon-lime flavor to the original iteration of the beverage.

Per Beer Street Journal, the 2017 release went well enough that MillerCoors decided to do it again the next year. The Milwaukee Business Journal wrote that the brewery was shocked at the demand in 2017 and produced 40% more in 2018. Apparently, that was not enough for the American public though, as Zima has not returned to these shores since then.