13 Kitchen Appliances Kids Today Have Never Seen

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Take a look around a modern kitchen, and you'll probably notice that the appliances in it are narrowed down to a core handful. There's the stove, fridge, a toaster, coffee maker, and probably a blender or food processor. Anything else — say a panini press or electric mixer — come off like something extra, a specialty appliance perhaps. Back in the 20th century, particularly the second half, many kitchens were a treasure trove of appliances. A lot of the machines inside would be unrecognizable to the kids of today. What were these bygone kitchen appliances, and more importantly, where did they go?

There are a few reasons why the throwback kitchen appliances we'll look at here fell out of fashion. The 20th century was a time of great mechanical innovation. There was practically no end to what could be dreamed up and sold to the masses. The mid-century also gave rise to the suburban housewife. Her cooking, cleaning, and child-rearing duties were many, so anything to make these tasks simpler had marketable appeal.

Several of these appliances are still made today, but exist more in the novelty space. After all, novelty was the uncontested muse for all these once-popular kitchen appliances. Some of them were so successful, they became key parts of well-appointed home kitchens throughout the world. Others were too nuanced to thrive or got replaced by more multi-faceted (and sometimes simpler) machines. Here are some of the kitchen appliances today's kids would struggle to identify.

Electric can opener

It started with a familiar sound, somewhere between a grind and a hum, that sent pets scampering to the kitchen and piqued the interest of children. This was the resounding call of the electric can opener, a common kitchen appliance in many homes during the latter part of the 20th century. Preston C. West patented the first electric can opener in December 1931, as a modern revision of the manual can opener, which was developed in the Civil War Era, and redesigned with a cutting wheel in 1925. West's can opener, however, was a little too ahead of his time.

Electricity in the home wasn't a widespread phenomenon in the early '30s, so West's modernized can opener didn't catch on. In 1956, two California-based companies gave the electric can opener a facelift. Klassen Enterprises introduced a wall-mounted version, while Udico released a free-standing model intended to be kept on the kitchen counter. Walter Hess Bodle engineered the prototype in his garage alongside daughter Elizabeth who sculpted it. The Bodles' design also featured a knife sharpener in the back.

Udico's electric can opener became the de facto model for decades. It was reproduced by just about every major kitchen appliance maker of its day, including General Electric, Sunbeam, Rival, and many more. Yet for the electric can opener, time was a cruel mistress. By the 21st century, most people reverted back to using manual can openers, which are dishwasher-safe, cheaper, and much less bulky to store.

Flying Saucer electric skillet

The Space Race of the 1950s influenced many facets of pop culture — kitchen appliances included. A few years earlier, in 1947, one of the first documented UFOs, or, "flying saucers" was sighted by a pilot near Mount Rainier in Washington state. This was also a time when society was asking itself, "what can't we plug in?" Casserole pans were not immune to the electrical craze, and with a little oomph from America's outer space infatuation, the flying saucer casserole pan entered the stratosphere.

In 1953, Sunbeam was the first appliance brand to introduce electric fry pans. Around that time, Presto also rolled out a line that included both an electric skillet and an electric casserole pan. Sunbeam and Presto kept their electric pan designs pretty straightforward, while competitors like Century Enterprises and Cory Corporation went with a "flying saucer" silhouette. Flying saucer pans are disc-shaped with a domed lid and winged handles and feet. All electric pans feature a dial to control how much heat they produce.

The now-defunct Cory Corporation sold its flying saucer appliances under the Cory Party Chef line throughout the 1950s. Prior to launching its Party Chef cookware, Cory Corporation was best-known for its innovations in the coffee space — most notably the vacuum-sealed coffee pot. Century Enterprises crafted its flying saucer electric casserole pan out of copper and named it the Futuramic Automatic Skillet.

Salton Hotray

The table spread at dinner parties in the 1950s and '60s was hardly complete if the hostess didn't break out the Salton Hotray at some point. This handy kitchen appliance was a mid-century mainstay — and a versatile one at that. Salton Inc. was founded in 1943 by Lewis Salton, an engineer who fled Nazi-occupied Poland in 1939 and settled in New York City. The Salton Hotray was his first of many ingenious kitchen appliances.

Necessity being the mother of invention is certainly true in the Salton Hotray's case. In New York, Salton worked long hours and arrived home after dinner most evenings. Rather than task his wife with having to reheat his dinner in the oven, Salton invented a warming tray on wheels that could be rolled wherever he decided to eat. Salton began selling his product to department stores and by the '50s, it was considered a household staple in the American home.

Over the years, Salton sold various sizes and styles of his famous Hotray. The Hotray cart on wheels was Salton's top-of-the-line model, featuring a solid brass and walnut frame. Over time, Hotray's popularity dwindled (vintage Hotrays are still sold as a rarity item) — likely due in part to the rise of the microwave.

Air popper popcorn machine

Popcorn's origins lie with the indigenous people of the Americas, who were among the first to heat and pop corn kernels thousands of years ago. In the late 1800s, Charles Cretors, a candy store-owner from the Midwest, converted a peanut roaster into the world's first popcorn machine using power from a steam engine and later, an electric engine. The Cretors Company developed an industrial-sized air popper in the late 1960s and by the '70s, small air poppers were gaining popularity as a home kitchen appliance.

The air popper popcorn machine allowed consumers to make their own popcorn at home and flavor it however they like. Prior to the air popper as a kitchen appliance, people popped popcorn on the stove in pre-packed aluminum bags from brands like Jiffy Pop. Using an air popper was a great way to avoid all the butter and salt inside the stovetop popcorn.

Microwave popcorn proved to be a booming market in the '90s and into the 2000s, and air poppers as a trusty kitchen appliance became less commonplace. In recent years, consumers looking to avoid ingesting the chemicals lining the inside of microwave popcorn bags have begun to embrace the air popper again. Not every kid will recognize one, but more than a few health-minded moms have made an air popper purchase purchase in the 21st century.

Presto HotDogger

In 1905, Northwestern Steel and Iron Works (renamed Presto in 1939), was a national leader in the pressure canning industry and got its start in the kitchen appliance market by developing the first saucepan-style pressure cooker for home use. Throughout the mid-20th century, Presto made catering to the busy homemaker its mission. Among the slew of appliances it developed in that era, one that hasn't retained its staying power is the HotDogger.

To kids today, a HotDogger sitting on the kitchen countertop would look like something from a past civilization, and well, that's because it pretty much is. The HotDogger sounds exactly like what it is: an electric cooker fitted to cook multiple hot dogs at once. Presto began selling the HotDogger in the 1960s. Remember how we said Presto loved making appliances for busy homemakers? This was an ode to that. All one had to do was impale both ends of a half-dozen dogs on the spikes inside the HotDogger, close the lid, wait 60 seconds, and voilá, lunch for you and the kids.

Kids of the '60s and '70s don't have the fondest memories of the HotDogger. On one Reddit thread discussing the HotDogger, many recalled that more often than not, the hot dogs would split, and make the machine a hassle to clean afterwards. There was also some chatter about the prongs on which the hot dogs were impaled being made of lead.

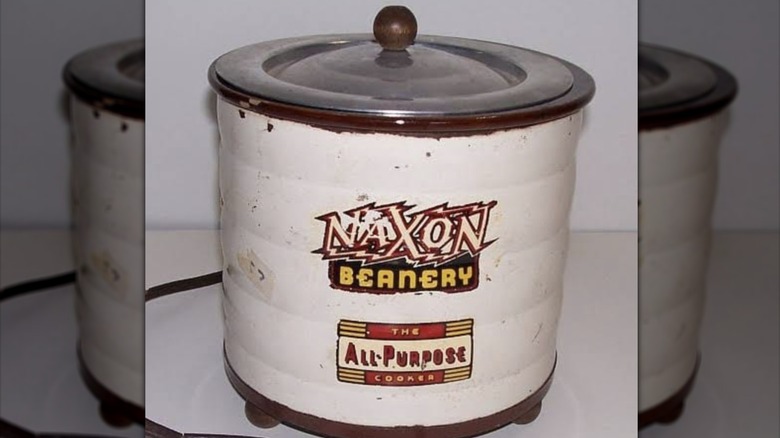

Naxon Beanery All-purpose Cooker

It's unlikely that modern kids are familiar with the Naxon Beanery All-Purpose Cooker, but most people would recognize the kitchen appliance that spawned from the Beanery's existence. Naxon Beanery walked so that Crockpot could soar. The inspiration for both lies deep in the home-cooked heritages of Eastern Europe.

The inventor of the Naxon Beanery was Irving Nachumsohn, who received the U.S. patent for his "cooking apparatus" in 1940. Growing up, Nachumsohn had heard stories about how beginning in the 19th century, the Jewish community of Vilnius, Lithuania prepared for the Sabbath by making a large crock of stew — consisting of meat, veggies, and beans — on Fridays before night fell and Sabbath began. The crocks would be placed into the ovens of local Jewish bakeries to slow-cook overnight in the ovens' dying heats. This stew was and is known as cholent.

Instead of relying on fleeting oven heat, the Naxon Beanery relied on electric heat dispersed throughout its inner chamber for an even cook. Nachumson sold the Naxon Beanery, through the 1950s before retiring and selling his design to Rival in the 1970s. Rival catapulted Nachumsohn's design into the Crockpot — an appliance that never went away.

Salton yogurt maker

Salton took a slightly different approach to 20th century kitchen appliances. Rather than just make food preparation easier, Salton created appliances that encouraged people to make foods that they would otherwise buy in a store. The Salton Yogurt Maker embodied this intention. The Salton Yogurt Maker came on the market around 1974 and allowed users to make five portions of homemade yogurt at once.

The process was simple enough. Heat milk in a saucepan on the stove, add a packet of yogurt starter culture (or use a little yogurt as a starter), let it cool to 110 degrees (a Salton Spoon Thermometer is included), then pour the mixture into the Yogurt Maker's glass jars. Secure the jars' lids, and place them inside the electric induction unit — the main component of the appliance. Fermentation time was ten hours, and another three or four hours was needed for cooling time before eating.

Although they're a less-common sight, yogurt makers are still sold, with many models closely resembling the Salton model. For years, store-bought sugary, brightly colored yogurts took attention away from homemade yogurt, but as trends tend to do, plain and Greek-style yogurt have circulated back into mainstream relevance.

Ice cream machine

Hand-cranked ice cream machines of the 19th century became ubiquitous enough that the wooden barrel freezers that housed these dessert-forward butter churns became a repeated motif for years to come. The mid-20th century was all about doing away with manually operated appliances, plugging in, and letting go. When the electric motor was incorporated into the ice cream machine, the rollout of a pint-sized, kitchen-friendly ice cream machine became possible.

Ice and salt are the main components that keep ice cream mix frozen, and once electricity took over, manual churning was no longer required. Downsizing the electric ice cream machine to a kitchen-friendly size was the kind of thing that appliance maker Salton specialized in. Salton manufactured its electric ice cream maker in Italy and added it to the brand's ever-growing line of kitchen appliances that encouraged consumers to DIY it instead of resorting to the product readily available in stores.

Salton was a chief purveyor of quirky appliances, and its blueprint for a modern at-home ice cream machine persists, albeit in a marginal sense. Craving an ice cream machine of your own? They're still made, but like many single-function kitchen appliances of yesteryear, it lives on as a novelty item.

Electric carving knife

For the busy housewife, why carve when you can buzz? Such was the thought process behind the electric carving knife. The earliest incarnation of the electric carving knife arrived in the mid-1960s. Inventor Jerome L. Murray, who had found success with electric-powered novelties like the peristaltic heart pump and the airplane boarding ramp decided to give some power to the humble carving knife — because sawing into bread, meat, and anything else really gets tiring.

General Electric proffered the electric carving knife in 1964, aimed at housewives who would simply need to guide the appliance and forgo the muscle. The grunt work was done by a pair of serrated blades that acted much like an electric hedge trimmer but was meant to slice up food. The electric carving knife was saleable enough that companies like Black & Decker and KitchenAid developed their own models.

Is the electric carving knife dangerous? Hell yes, and that's probably why you don't see it around much today. Carving knives are dangerous too, but they don't slice things up on their own like their electric counterparts.

Peanut Butter Machine

After bursting on the scene with its ingenious Hotray in the 1950s, Salton Inc. spent the next several decades continuing its quest to simplify life for the home cook. In 1975, it unveiled the Peanut Butter Machine, a downsized, domestic version of the industrial machine. The inspiration was simple. Salton recognized the purity in the peanut butter machine's function — nothing but peanuts had to be added to the machine to get great tasting, fresh peanut butter.

The peanut butter machine operated like a meat grinder for peanuts. Small steel wheels ground up the peanuts poured into the hopper (tree nuts could also be used) and within two to seven minutes, a half-pound of fresh peanut butter was yours. In the '70s, consumers embraced what Salton was selling.

From a certain angle, the peanut butter machine read a little gimmicky. Between purchasing a bulk quantity of peanuts and the machine itself (plus some extra jars and lids), investing in a peanut butter machine (which retailed for $29.95 in 1975) didn't actually save money in the long run. At the time of its release, an 18-ounce jar of Skippy Super Chunk peanut butter cost 99 cents.

Vacuum Coffee Pot

Coffee machines lend themselves to incessant innovation, and in the early 1900s, fixation on the vacuum coffee pot was real. Silex Company ushered the vacuum coffee brewer into American consciousness in 1915. It was a two-tiered appliance that used pressure to heat water in a lower glass chamber, raise it to the upper glass chamber, brew the coffee grounds, and suck the brewed liquid back into the bottom portion. It's similar to the still-popular moka pot percolator, but more scientific looking.

Silex was a leader in vacuum coffee pots, but as it worked to patent new and improved gasket seals between the appliance's two chambers, competition arrived. Cory Corp, the enterprise of inventor Harvey Cory, built its business on a glass coffee brewer that was very similar to what Silex had going on. Cory actually beat Silex in the patent race for vacuum pot modernization. The company submitted a patent for a vacuum pot featuring a glass filter rod in 1942 — Silex didn't perfect its version of the same design until 1946.

Both companies were intuitive enough to see the impending culture shift. Instant coffee and the automatic drip coffee maker grabbed ahold of the public's attention and didn't let go. Vacuum coffee pots are still around, but you'll most likely find them in the clutches of adventurous coffee snobs the world over — the average consumer has long been preoccupied.

Electric egg cooker

The electric egg cooker was patented in 1916 by Marshall Hanks, founder of Hankscraft Inc. The Hankscraft Egg Cooker, was the first appliance sold by the Wisconsin-based company. You can find '30s-era Hankscraft Egg Cookers on the second hand market today (that still work!), but the average kid would gaze upon its petite silver cloche and colorful ceramic body with befuddlement.

The Hankscraft Egg Cooker used closed circuit electricity to heat the water inside and boil the eggs. Once the water evaporated, the circuit would break and the machine would shut off. The amount of water added to the egg cooker would dictate the cook time. Hankscraft Fiesta go-along egg cookers — the vibrant-colored ceramic ones — were first produced toward the end of the 1920s. They were meant to "go along" with the Fiesta dinnerware line made by the Homer Laughlin China Company. Hankscraft also made double egg cups inspired by the Fiesta dinnerware design.

Meanwhile, competitors like Sunbeam and Hotpoint wasted no time developing electric egg cookers of their own. Both brands riffed on Hankscraft's simple, circular design but could hold six eggs rather than the typical four of the Hankscraft Egg Cooker.

Frigidaire Flair

If there was ever a kitchen appliance of yore worthy of a revival, it's the Frigidaire Flair. It's sleek, well-engineered, and cute. The Frigidaire Flair was immortalized as Samantha's kitchen range of choice in the classic television series "Bewitched," but would look equally stylish inside a minimalist's apartment in the 2020's. General Motors owned the Frigidaire name when the Flair made its commercial 1962 debut.

At the time, the Flair was advertised as being equipped with a boatload of automatic features. There are two ovens with vertically lifting doors, a moveable range hood, and an electric stovetop that pulls in and out like a drawer. Several of the Flair's design features were designed by M. Jayne Van Alstyne, who helmed the research and development arm for Frigidaire at the time and was entrusted with maximizing the feminine appeal of Frigidaire's kitchen appliances.

Numerous online forums are dedicated to enthusiasts of the Flair, many of whom own still-working models. Replacement of the electric burners or oven components is often needed, and spare parts can be tricky to find. Yet the design itself has an air of timelessness.