Porterhouse Vs T-Bone: The Steak Showdown

At any steakhouse, you'll have a choice among a wide range of cuts, from filet to strip, sirloin to flank. But perhaps the be-all and end-all of steakhouse steaks are behemoth, bone-in marvels, presented on a platter and often tailor-made for sharing. Both t-bones and porterhouses fit this description, and indeed, according to chef Michael Vignola, culinary director of Catch Hospitality Group, these are some of the best steaks for a crowd. A porterhouse, he says, is "great when cooking for a group, as it affords both textures of a sensuous soft filet versus the unctuous strip."

At first glance, it could seem as though both T-bones and porterhouses — the latter of which Max Crask, executive chef at Madrina in St. Louis, notes can also be called "bistecca fiorentina," seeing as they're so beloved as a traditional sharing steak in Tuscany — are one and the same. Both, after all, boast two very different textures within one steak, divided by an impressive central bone. In fact, it could be said that porterhouses are a member of the T-bone family. But a few subtle differences actually make these two steaks worlds apart. Here's everything you need to know about T-bones and porterhouses.

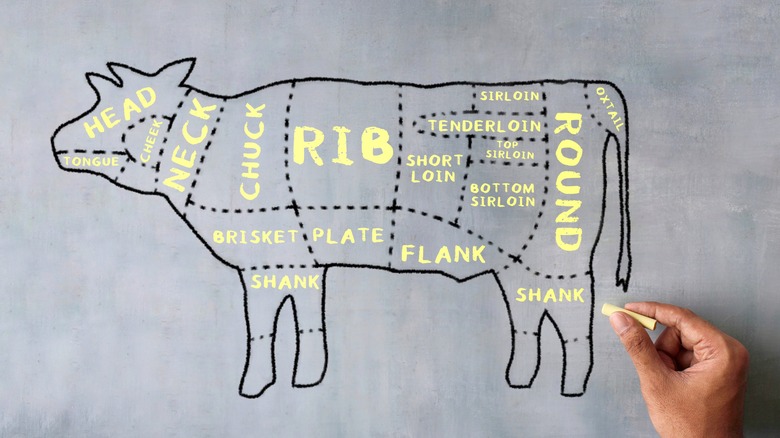

Both come from the short loin of the steer

If T-bones and porterhouses appear to be so similar, it's chiefly because they both come from the same section of the cow. The short loin is a part of the loin primal, a section of the steer below the backbone, between the rib primal closer to the shoulders of the steer and the sirloin primal, just before the round.

The short loin is known for being home to some of the tenderest cuts of steak, including the aptly named tenderloin — and that's no surprise. According to the experts from the Cattlemen's Beef Board and the National Cattlemen's Beef Association, "The further it is from horn or hoof, the more tender the cut." Seeing as the short loin is very close to the center of the steer, it shouldn't shock anyone that it's where the tenderest steaks on the steer can be found.

Porterhouses typically come from the back of the short loin

While given their location in the short loin, both T-bones and porterhouses tend to offer a standout tender texture, they are not exactly the same. Despite coming from the same general area of the cow, porterhouses come from further back along the subprimal than T-bones do, closer to the sirloin area, where steaks tend to be known for their leanness.

This, according to Max Crask, means that one can expect slightly more chew from the porterhouse than from a T-bone: Seeing as "it moves farther from the head and hoof," he explains, the porterhouse is less tender than a T-bone, which will typically have more marbling than a porterhouse will. The flavor of both steaks, however, is largely the same, despite this slight discrepancy, boasting big, beefy flavors and a tender yet toothsome chew. It's no surprise both steaks are so popular.

Both T-bones and porterhouses contain strip steak

The bone running through the middle of both porterhouse and T-bone steaks isn't just there for decoration: It actually divides the two individual steaks that make up these hybrids. Both porterhouses and T-bones, in other words, are comprised of two different muscles, one of which is the strip steak, known for its exceptional balance of beefy flavor, succulent tenderness, and just enough fat to make it delicious.

In the world of strip steaks, two cities go head-to-head on most steakhouse menus. The difference between New York and Kansas City strip steaks, however, has nothing to do with geography, coming down instead to one simple difference: the presence or absence of a bone. Simply put, a New York strip is served off the bone, while a Kansas City strip is served on the bone. For this reason, according to Matthew Kreider, executive chef at Steak 954, "I would consider both steaks to have a KC strip."

The strip steak on a porterhouse contains a vein

T-bones have one major asset as compared to porterhouses when it comes to their texture. Porterhouses, unlike T-bones, often have a "vein" running through the strip side of the steak, according to Matthew Kreider. Actually a tough line of sinew, this "vein" is evidence that the muscle has experienced more work during the steer's life, and it can be unpleasantly tough to try to chew through, often needing simply to be subtly spat out.

Luckily, not all porterhouses have this vein. The biggest porterhouses tend to be "vein-end" porterhouses, and while these porterhouses are usually the most imposing and impressive, they are less pleasant to eat, given their chewy texture. Smaller porterhouses, much like T-bones, meanwhile, do not boast this vein. So look past mere size in this case, and choose the smaller porterhouses to be rewarded with far more tender, succulent meat.

Both T-bones and porterhouses contain tenderloin

Just opposite the strip, on the other side of the bone, the steak on both T-bones and porterhouses is one of the tenderest — and the most expensive — on the whole steer: filet mignon. Filet mignon is one of the most sought-after steaks on the whole steer for a number of reasons.

Firstly, it represents a fairly small proportion of the entire steer, seeing as there are only two filets mignon on each cow, and each one is just 4 to 5 pounds in weight. And because this steak comes from a muscle at the top of the cow, just ahead of the hind legs, that does very little work when the cow is still alive, filet mignon is super tender with no connective tissue to speak of. Buttery and lean, filet mignon isn't the most flavorsome on the cow by any means, but what it lacks in robust beefiness it more than makes up for in tender texture.

Porterhouses have more filet mignon than T-bones

Perhaps the most essential difference between a porterhouse and a T-bone is the size of the filet: porterhouses simply have more of it. This stems, in large part, from where it's found on the steer. Seeing as it comes from further back, Matthew Kreider explains, "the porterhouse will [...] have a much larger portion of filet."

"A T-bone," he adds, "will be thinner and have a smaller filet due to where it is cut from, the front of the short loin." And this isn't just a question of location. To be deemed a porterhouse by the USDA, porterhouses must be cut slightly thicker than T-bones, with a filet at least 1 ¼ inches thick. "Anything smaller," says Andrew Lim, chef and owner of Perilla Korean American Steakhouse, "is a T-bone steak." A T-bone, meanwhile, explains Michael Vignola, has no size requirements.

This more imposing size means that porterhouses regularly weigh upwards of 2 pounds, making them many chefs' go-tos. "I prefer a porterhouse," says Kreider, "as the larger filet typically cooks to a more consistent temperature to the striploin. I also prefer a thicker steak." Even Lim, despite not usually being a fan of either strip steak or filet, prefers a porterhouse over a T-bone. "It has more of the tenderloin portion," he says, "which is usually super tender."

T-bones are cheaper than porterhouses

It should be no surprise, given the consequential size of a porterhouse as compared to a T-bone, that the latter is far less onerous — and this for more reasons than one. Not only are T-bones lighter than porterhouses, but because porterhouses have a larger ratio of more expensive filet as compared to strip, they tend to fetch a higher per-pound price. Wilson Beef Farms, for example, prices its T-bone at $18.49 per pound, for a total of approximately $14.80 per steak. They price their porterhouses, meanwhile, at $20.89 per pound, for a total of $16.72 for a ¾-inch thick steak.

But just because it's a little bit less expensive doesn't mean a T-bone is not a good steak. "I think if you want a bone-in, more price appropriate steak like a strip, a T-bone is a good choice," says Matthew Kreider. "However, if you are sharing and someone prefers a filet or a thicker steak, stick to the porterhouse."

Both steaks can benefit from dry-aging

Dry-aging is all the rage these days to impart even more flavor to beef. Any steak can benefit from this method, according to Michael Vignola, which "pulls out the water weight and intensifies the marbling within the meat," he says. But for our experts, both T-bones and porterhouses are particularly well-suited to the method. "Bone in steaks definitely benefit from dry aging," says Matthew Kreider. "The aging process also helps to create a better texture, as sometimes strips can be very chewy." And even the filet can benefit, he adds, noting, "I really appreciate the dry aged filet on the porterhouse. I don't typically eat filets, but I find the age makes them much tastier."

When it comes to how long these steaks should be aged, bear in mind that the longer you age it, the tenderer — and funkier — it will become. "I like my steaks aged longer (40-plus days)," says Kreider, "But like everything else it is about preference. I find you start to notice dry age around 21 days, so I would not go for less than that." Max Crask adds, "If you have some love for stinky cheese, a nice six-month age is what you're looking for."

It can be hard to cook either steak perfectly

Anyone who's roasted a turkey only to find the breast bone dry by the time the legs are done can understand the difficulty of cooking a steak with two cuts on the same bone. Andrew Lim notes that tenderloin should be cooked "a few degrees less than" strip, with tenderloin ideally enjoyed at between 125 and 130 degrees Fahrenheit and strip between 130 and 135 degrees Fahrenheit. "The tricky thing is that the tenderloin always seems to get slightly overcooked," says Max Crask. But our experts have a few tricks.

Start, Lim suggests, by letting the steak temper to room temperature. "This should ensure even and controlled cooking," he says. With a thinner porterhouse or a T-bone, Crask recommends a hot sear, finishing it on the oven, or grilling the steak and leaving it on the colder side of the grill to ensure it comes to the proper temperature all the way through. Thicker cuts, he says, benefit from a reverse sear or a sous vide method. "With these bone-in cuts, a low temperature (127 degrees Fahrenheit) bath for a couple of hours can pull quite a bit of flavor out of the marrow and keep the steak medium rare all the way through."

If you want to reduce the guesswork even further, Michael Vignola suggests simply taking the steak apart. After searing it on both sides, slice off the filet and let the strip roast a touch longer so that both steaks are cooked to perfection.

Both are great cooked over an open flame

If you want to get the best flavor out of your beef, our chefs recommend taking advantage of perhaps the oldest cooking method. "I would prefer open flame for both steaks," says Matthew Kreider. "When I was in Florence, Italy they cooked their bistecca alla Fiorentina over olivewood. Typically, they use an aged porterhouse. It was a great experience."

Michael Vignola agrees, noting his preference for hardwood charcoal whenever cooking larger pieces of beef. Given the high heat of this method, he says, diners are rewarded with "a delicious salt and pepper crust that transforms the meat into something greater than the sum of its parts." If you don't have access to hardwood charcoal, he says, a comparable effect can be produced under the broiler, which offers a similar surge of high heat to ensure you get the perfect crust to contrast with the juicy, tender meat within.