Who Is Fanny Cradock, England's First Female Celebrity Chef?

Fanny Cradock's show "Kitchen Magic" premiered in the U.K. in 1955, and it made her a national sensation. Dressed in evening gowns and sporting heavy makeup and impeccably coiffed hair, she barrelled through recipes that, from a 21st-century perspective, are almost too eccentric to believe. As it happens, she may have belonged to the category of celebrity chefs who are actually terrible cooks, but that didn't stop her from being one of the most influential celebrity chefs of all time. Nearly a decade before Julia Child's "The French Chef" burst onto American screens, Cradock was coloring mashed potatoes green and berating her on-screen assistants.

At the time, television was rare, let alone cooking shows and celebrity chefs. Only 9% of households in America had a television set in 1950. By the end of the decade, 85.9% did. In the U.K., the increase in ownership was just as swift, with about 75% of households owning sets by 1960.

These days, there is a celebrity chef to fit every viewing preference. Over the past two decades, we've been able to follow the traditional chefs, like Ina Garten and Jamie Oliver; the rebellious chefs, like Anthony Bourdain and Gordon Ramsay; and the controversial chefs everyone hates working with, like Paula Deen and the now-disgraced Mario Batali. When Fanny Cradock started her show on the BBC, however, there was no roadmap, and although she is regularly overshadowed by the towering influence of Julia Child, she pioneered the genre.

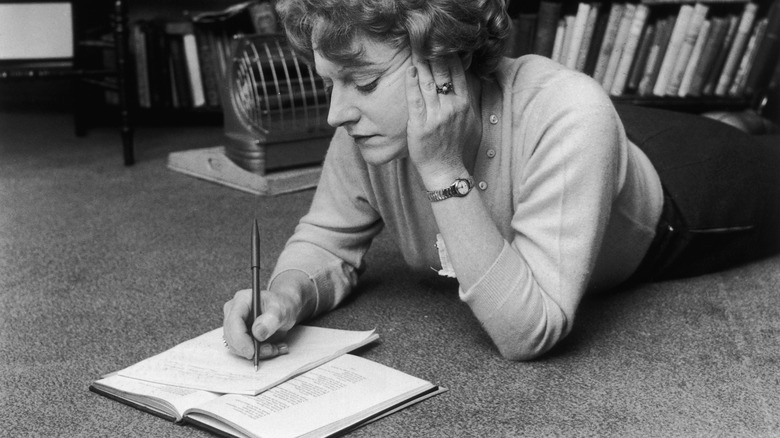

[Featured image by Allan Warren via Wikimedia Commons|Cropped and scaled|CC BY-SA 3.0]

She had a complicated personal life

Despite the level of celebrity she gained later in life, Fanny Cradock's origin story was a source of constant revision. She was born in 1909 as Phyllis Nan Sortain Pechey in Leytonstone, a town southeast of London. She would later claim that her father was a wealthy novelist and gambler, but he was, in fact, a corn merchant. When she was only 1-year-old, her parents gave her away to her maternal grandmother, reportedly as a birthday gift. She married at 17, and was left widowed and pregnant not long after when her husband, an RAF pilot, crashed his plane and died. At 19, she married again, but eventually left her new husband and their 4-month-old son.

Moving to London in her early 20s, Cradock sold vacuums and worked as a dressmaker, but didn't earn enough to be able to look after her first son. Just as her parents had done, she gave him away to his grandparents. In 1939, she married for the third time without having divorced her second husband. Eight weeks later, she met and fell in love with John Cradock, a major in the British army. She took his last name and they stayed together for the rest of his life, but it wasn't until 1977 that they married. At the time, her second husband was still alive, making it her second bigamous marriage.

She began as a columnist and restaurant critic

Early in her relationship with Johnnie, Cradock joined the British Housewives' League, which called for the government to end the restrictive food rationing it imposed early in World War II. Through the League, she landed a job with the Daily Telegraph writing about fashion and beauty, two interests that shone through on her cooking show years later.

She was also writing books at the time. Her first cookbook, "The Practical Cook," was published in 1949, and soon afterward the Daily Telegraph began sending her to hotels and restaurants to write reviews. She chose to write under the pseudonym Bon Viveur, a French term referring to someone who lives well.

She and Johnnie traveled around the U.K. and abroad for the Bon Viveur column and gained an avid readership. Their popularity may have been down to good old fashioned escapism. At the time, Britain was emerging from the war, its cuisine in tatters. Rationing was still in full force, and upbeat reviews about fancy international foods may have been a balm to Cradock's readers.

She was Britain's first TV cooking star

Much of Cradock's biography is murky, largely due to her penchant for fabrication, but one thing that is not disputed is that she was Britain's first celebrity television chef. Some even argue that she was the first celebrity television chef, period. Glimmers of her celebrity potential must have been apparent in early years, as she and Johnnie performed cooking demonstrations in front of live audiences. These performances, which they called "Kitchen Magic," were so popular that the couple sold out the Royal Albert Hall during a Christmas show in 1956.

Cradock's television cooking show debuted on the BBC in 1955. Also called "Kitchen Magic," it featured Johnnie playing a similar sidekick role as he did during their stage performances. The concept involved making a three-course meal for eight guests on a budget, and sealed their celebrity status. Cradock went on to star in a show for ITV called "Fanny's Kitchen," and things took off from there. For the next 20 years, she was an ever-present figure on British screens, appearing in shows like "Chez Bon Viveur" in 1956, "Giving A Dinner Party" in 1969, and "Cradock Cooks For Christmas" in 1975. She even had a recurring slot on the kids' TV show "Lucky Dip" in the early '60s in which she had a sequence called "Happy Cooking."

She had a very different persona to Julia Child

As a middle-aged woman and the first television cooking celebrity, it's impossible not to draw comparisons between Fanny Cradock and Julia Child — but watching even 30 seconds of their respective shows will reveal just how different they were as on-screen personalities. What made Julia Child exciting to Americans wasn't just the extravagant French recipes she was teaching them, but her warm, relentlessly positive persona. Cradock, on the other hand, was defined by a chilly imperiousness bordering on condescension. She was even brusque with the food she prepared, sharply rapping on the crunchy skin of a roasted leg of pork with a carving knife or demonstrating how to open a can of sardines with a pair of pliers and a metal skewer.

Before American audiences had their confidence buoyed by Julia Child's vigorous encouragement, British audiences delighted in the particular kind of indiscriminate harshness Cradock showed her colleagues, bosses, and underlings on and off-screen. With her cut-glass accent (for her, the word "several" had three syllables and a rolled "r") and thick makeup, she would almost certainly have been a camp icon if she appeared on screen today. At the time, however, there was no indication audiences received her with anything other than earnest fascination.

Her husband played a key role in her career

Although Cradock became a celebrity in her own right, her ascendency to fame was deeply entwined with her partner, Johnnie. They wrote the Bon Viveur column together, and their initial live performances hinged on their chemistry. They were billed as Major and Mrs. Cradock, and they performed a type of marital dynamic that was popular on television at the time. He was the browbeaten husband and she was the domineering wife. Her sharp, dismissive tone became a trademark in her cooking show, and it was Johnnie who was her first target. His role was to sneak sips of wine and pass Fanny whatever kitchen equipment she demanded from him.

Despite this public performance of their relationship, the couple were inseparable from the time they met in 1939 until Johnnie died in 1987. They enjoyed the high life once their fame ushered in wealth. They had a boat in Cannes, a Rolls Royce, and a house in an exclusive part of London. When Cradock's television career came to a screeching halt, they moved to Ireland to evade taxes and practiced faith healing together. Their on-screen dynamic may have been a complete fabrication, but their attachment lasted nearly five decades.

She dressed to the nines for her cooking show

It is difficult to overstate just how elaborately Cradock dressed for her public appearances. In the live show at the Royal Albert Hall in 1956, she entered wearing fur, white gloves, and glittering jewelry. Early in her television career, her fashion choices could be more reserved than those she made later on, but even then she never stooped to wearing an apron.

As her career expanded, however, Cradock's fashion intensified. She wore fake eyelashes, dark lipstick, and had artfully constructed hair. In one 1963 episode of "Kitchen Magic," she changes outfits four times, starting in a dark pink sleeveless dress with a flowing sash over her shoulder and ending with a cocktail dress with a bold, abstract pattern. In one of her Christmas specials, she wears a bright orange dress with loose sleeves and a deep v-neck, a huge black bow in her hair.

A 1975 episode in which she teaches her audience how to make a mincemeat omelet might take the cake as far as fashion goes. In it, she wears a bright pink dress with wide, kimono sleeves and a large metallic gold belt. A double string of pearls and bright pink hair ornament complement the ensemble, and her white-powdered face and thinly-drawn eyebrows give her an exaggerated appearance. Her stylistic choices may not have been the main draw of her shows, but they certainly added to her air of magnetism.

Her cooking style was eccentric

In addition to her bold fashion choices, Cradock was a maverick in the kitchen. Even during an era that produced foods we're glad to see gone (fish meringue pie, anyone?), she took some big culinary swings. One of her most frequent ingredients was food coloring. In some situations, it made sense. For example, in one of her Christmas specials, she unveils her take on brandy butter, a towering swirl of green butter mixed with brandy and dotted with brightly-colored candies to mimic a Christmas tree.

In other instances, its purpose was more difficult to pin down. Cradock made cheese ice cream, a mixture of ice cream, gruyere cheese, and green food coloring. She turned hard-boiled eggs blue. She mixed green dye into mashed potatoes. In a textbook display of culinary maximalism, she even served swan with gold leaf, never mind that it was treasonous for all but a small minority of wealthy landowners to own or kill swans until 1998 (and illegal since 1981).

For Cradock, presentation was paramount. When serving a whole salmon, she not only used cucumber slices to give the impression of scales but piped eyes back into the head. On another occasion, she served pigeon and kept the feathery wings on-hand to stick back into the cooked flesh for serving. These recipes might not sound particularly appetizing, but Cradock was ahead of her time when it came to producing head-turning recipes that kept audiences hooked.

Her prawn cocktail recipe was famous

Cradock is sometimes credited with having invented the prawn cocktail (also known as the shrimp cocktail to Americans), and although this is unlikely, she played a key role in popularizing it. With its sophisticated presentation in cocktail glasses and mixture of intense flavors, it's no wonder the flamboyant chef took to it wholeheartedly.

Before Cradock made it her own, the dish (likely invented in the U.S.) was mentioned on a popular British soap opera in 1962. It was one of the few dishes Cradock made that became a hit, no matter how much one might wish that blue eggs and fruit-filled omelets had become ubiquitous.

Cradock's recipe was published in 1967, and her wording provides a glimpse into her colorful approach to cooking. She described the dish as "a sordid little offering" and said that the prawns should be "drooping disconsolately over the edge of the glass like a debutante at the end of her first ball," according to The Guardian. The lemon on the other side of the rim should be clutching the glass "like a seasick passenger against a taffrail during a rough Channel crossing." Partly due to Cradock's recipe, the shrimp cocktail became one of the most popular starters of the 1970s and still appears on menus as a retro classic, often with the addition of Marie Rose sauce.

She loved French cuisine

If there was an overarching theme to Cradock's cooking, it was her love of French cuisine. In the 1950s and '60s, British food was struggling. The rationing that had been imposed on the country since the beginning of the war meant that people had grown accustomed to limited ingredients and bland flavors. During that period, Cradock was hostile toward British food, even claiming that there was no such thing as English cuisine.

Cradock's love of French food and culture was made plain when she chose Bon Viveur as the byline for her Daily Telegraph column. Unlike Julia Child, who had trained at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris, Cradock did not have any French cooking experience, but looked to the country — and in particular famed French chef Auguste Escoffier — as a guiding light. She favored French meringues and added brandy to just about everything. Her lack of expertise in French cooking might have been glaringly obvious to those who had some familiarity with it, but Cradock had a cuisine all her own, and it was enough to keep her audiences tuning in.

Her career ended in disgrace

The harsh persona that made Cradock a star was also what ended her career. In 1976, she was set to appear as a mentor on the popular reality TV show called "The Big Time," in which members of the public were given the opportunity to try their hand at "the big time" version of their favorite hobbies. One contestant got to conduct an orchestra at a large London venue, another got to take a shot at being a TV presenter, and another went head-to-head with a professional wrestler in a public match.

Cradock's episode involved a farmer's wife named Gwen Troake who was tasked with cooking a celebratory meal for former prime minister Edward Heath at the Dorchester Hotel. As Troake listed the dishes she would be making, Cradock rolled her eyes, grimaced, and even pretended to throw up in her mouth (twice).

Troake's menu might not have been the definition of haute cuisine, but it was far from repulsive. It consisted of a seafood cocktail (one of Cradock's signature dishes), duck made with blackberry jam, and rum and coffee cream pudding. Cradock's unbridled disdain didn't go over well with audiences. They were not yet accustomed to tyrannical television chefs ripping hopeful amateurs to shreds, and the incident ruined her career. Even The Daily Telegraph, the paper that had made her a celebrity, wrote, "Not since 1940 can the people of England have risen in such unified wrath".

She published dozens of books

Amidst all the TV shows and newspaper columns, Cradock also managed to rack up an extensive bibliography. In the early years of her relationship with Johnnie, she started writing novels under the name Frances Dale, including "Women Must Wait" in 1944, "The Land Is In Good Heart" in 1945, and "O Daughter of Babylon" in 1947. She also wrote 10 children's books during this period.

During the peak of her on-screen cooking career, Cradock started writing a series of historical novels. The first, "The Lormes of Castle Rising," was published in 1976 and was followed by nine others. Her final novel, "The Windsor Secret," was a fictionalized account of the romance between Wallis Simpson and King Edward VIII.

Between 1949 and 1985, she published dozens of cookbooks, often in collaboration with Johnnie and, at least in the beginning, under their joint Daily Telegraph pseudonym, Bon Viveur. The topics were eclectic, including a children's cookbook, a collection of recipes from "Sherlock Holmes," and one entitled, "Coping with Christmas." She also wrote nearly two dozen travel guides to locations around Europe. In 1960, she published her first memoir, "Something's Burning." All told, Cradock wrote or contributed to around 100 books.

Her fans included the Queen Mother, Amy Winehouse, and Gordon Ramsay

Cradock's fall from grace was swift and, aside from a few guest appearances on game and talk shows before her death in 1994, permanent. Today, she isn't a household name the way other celebrity chefs of the '70s are, but during and after her lifetime, she enjoyed many high-profile fans. Chief among them was the Queen Mother (the mother of Queen Elizabeth II) who told Cradock and Johnnie that she credited them with improving British cuisine after the war. Cradock admitted to being so startled by the compliment that she forgot to curtsey.

One of the most unlikely Cradock admirers was Amy Winehouse. When the R&B singer's husband, Blake Fielder-Civil, was in prison, she allegedly told reporters she was planning to welcome him home with an old-fashioned meal in the mold of the retro chef. "I'm all about Fanny Cradock," she said, according to The Guardian.

Finally, as the original ruthless celebrity chef, it is only fitting that Cradock should find Gordon Ramsay among her most passionate fans. Not only has he cited her as one of his dream dinner guests, but he also shaped part of his show, "The F Word," around her legacy. During season 3, he ran a competition to "find the next Fanny Cradock." There were 9,000 entries, and the winner, Ravinder Bhogal, is now a successful cookbook author and chef in her own right. It's worth noting, however, that she has not attempted to emulate the inimitable Cradock.