What Is Aspic And Why Don't People Cook With It Anymore?

Aspic seems like an old food fad that no one wants to deal with anymore, but that's not true. This meaty gelatin has a long history and has been used for everything from food preservation and waste prevention to signaling that someone aspires to greater social heights. But, aspic hasn't been on the mainstream U.S. food scene radar for years. However, it's still been a vital part of so many other cuisines, and now it's making a comeback across the nation.

Aspic is a great example of how food in the U.S. has changed from being all about simple home cooking to being all about marketing and industrialization. It's the dish that led to the invention of powdered gelatin and that allowed women to unleash scientific creativity at a time when they had limited options for doing so. While many aspic recipes are understandably treated as odd now, they were created with efficiency and nutrition in mind. And as more chefs focus on aspic once again, here's a look at what it is and why people haven't been cooking with it as much as they used to.

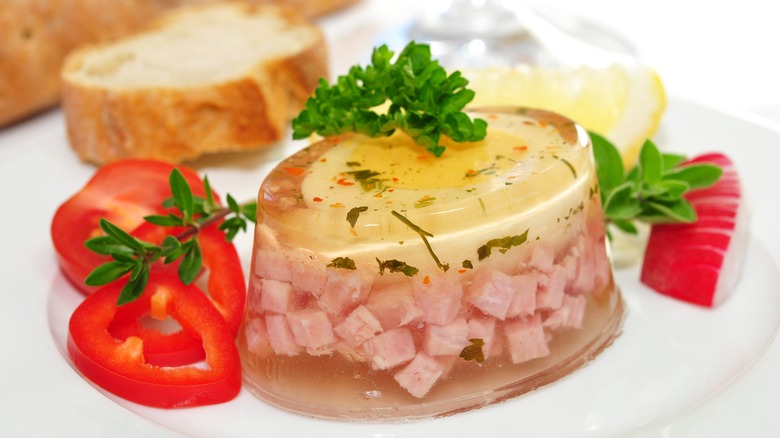

Aspic is a meat-based gelatin

Aspic is essentially a savory gelatin mold made with broth or stock. It's a fantastic way to prevent bacteria from reaching food because the aspic acts as a barrier that seals off whatever's been suspended inside it, although aspic doesn't necessarily need to have food inside it. Aspic can be used inside or alongside other ingredients, but it's best known as the jiggly gelatin stuff that holds a bizarre mix of foods and that is molded into some fancy, towering shape. In the 1800s and 1900s, those molded mixtures were known as molded salads, gelatin salads, and eventually Jell-O salads.

A basic aspic recipe sounds a lot like bone broth or any broth that's filled with collagen. You have to boil bones for hours to get a stock that you strain until it's clear, and then you cool it (via refrigeration) so that it starts to solidify. You can add gelatin to make the solidification process go more quickly. Aspics are often made from beef or pork, but vegetarian versions using agar are possible, too.

People have still been cooking with it

Aspics are not actually completely obscure. Many cuisines still use them, especially those that originate from outside the U.S., such as Eastern European cuisines. If you've ever had soup dumplings or xiao long bao, the "soup" inside each dumpling is actually a heated and liquified pork-stock aspic. In fact, when you make soup dumplings, you have to create a block of meat gelatin that you then chop up and mix with the other ingredients before placing the filling inside each dumpling. Steaming the dumplings melts the aspic and creates the soup.

Aspics are still common in two U.S.-based cuisines. One is tomato aspic in the South, and the other is savory Jell-O salad, which still lives on in Utah and other Mormon communities. It's so popular there that you're likely to find multiple savory gelatin salads when you're at some sort of gathering. So, aspic never really went away in the U.S.; it just got more specific in terms of where it remained popular.

It's actually a centuries-old recipe

Aspic wasn't some invention of a crazed gelatin maker. It's an old technique for preserving food; cooks would encase meats and other perishables in aspics to delay spoilage as early as the 12th century. The clear aspic also provided people with a look at an arrangement of food, and this became a major driver of aspic's popularity over the centuries. The way the food was placed in the aspic, how it was molded, how it was colored, and so on, was seen as a way to show off skill and create an elaborate dish for royalty and upper-class families.

Aspics came over to the U.S. with those upper-class families and their cooks. Chefs at high-end hotels would make aspics for guests, and the dish generally remained as it had for centuries — the territory of the elite. But by the late 1800s, that changed drastically as more household cooks produced aspics for their families.

A shortcut made it more accessible

As more households began to make aspics, a complaint emerged: While using sheets of gelatin made it a little easier to produce an aspic, soaking the sheets was still time-consuming and annoying. Women were making aspic salads at home, but by the 1890s, the process of soaking the sheets of gelatin was beginning to wear on people. An advocate for those home cooks asked Knox, which produced gelatin, if there weren't an easier way to use gelatin, such as in powdered form. Knox answered, and soon home cooks had this lovely powdered stuff that needed no soaking. That saved time, and it wasn't much longer until flavored and colored Jell-O was created.

Now that aspics were so easy to make, gelatin companies went to work marketing them. Knox held a contest to find recipes that used the new powdered gelatin, housewives started making those recipes, and Jell-O created advertisements positioning the flavored mixes as perfect for housewives who didn't have a lot of time but who did want to make impressive dishes. Soon, aspics became a standard recipe for many families.

It grew in popularity thanks to the industrialization of food

Food and the world of home cooking began to undergo a stunning transformation that hadn't been seen before. They were becoming industrialized, with the domestic science movement aiming to modernize home cooking, making it more efficient and cleaner, as well as more nutritious. In fact, that advocate who asked Knox for powdered gelatin was a member of this movement.

Home cooks latched onto aspic as part of this movement. A major advantage of aspic was that it was neatly molded food that didn't leave bits and pieces everywhere. You could unmold an aspic without splattering, and everything was contained in this artistic-looking bundle of gelatin. Even better was the fact that you could put just about anything into an aspic, including proteins and vegetables. The presence of an aspic on the dinner table was a sign that the kitchen likely had a refrigerator, something that wasn't that common in the early decades of the 20th century. Aspics, in all their strange glory, were now a sign of a modern and elegant kitchen.

Test kitchens started creating weirder concoctions

Once powdered gelatin was invented, both Knox and Jell-O's parent companies had their test kitchens creating recipes that used their respective products, as you'd expect from any food company. But these weren't just a few recipes meant to help cooks that were new to the products. The test kitchens created more and more — and stranger and stranger — combinations for housewives to try out. And they produced them in overwhelming numbers.

These odd combinations may have been the result of society's view of "women's work." Working in these test kitchens was really the only acceptable way for women to be in anything resembling chemistry and lab research. While women were actually working in those fields, of course, it really wasn't very common at that time. Women were thought to be taking care of the home, not playing around with test tubes. So now you had these kitchens full of women who wanted to do more with their lives but who couldn't, and they let their creativity loose when working with aspic recipes.

Combinations were presented in high-end magazines

As mentioned, aspics were originally something that mainly the upper class, the elites, and royalty had. As more home cooks outside those groups started making aspics, especially after powdered gelatin was created, the dish became less of a rarity. But gelatin companies kept marketing aspic as something that wealthy or cultured people would have by printing the recipes from their test kitchens in high-end magazines. That made it seem like aspic was still aspirational; if you made those recipes, the logic went, you'd be elevating your mealtime to a level similar to what high society had. You would be creating a work of art, just with more convenient ingredients.

After World War II, when many manufacturers were coming out with more convenience food in boxes, housewives faced a double-edged sword. They wanted to use convenience foods to save time, but if the food was too convenient and too easy to make, then they looked like they didn't care about their family. That would have been socially devastating and a major blow to their reputation because they would have looked like they were lazily slapping food onto a plate. With aspics, though, they could use these convenient ingredients like powdered gelatin while still making something that looked like it required effort, thus retaining their standing in the eyes of society.

Aspics became a way to use food scraps

Because an aspic didn't have to have a specific type of food embedded in it, it became a great recipe for using up smaller amounts of food that weren't enough to turn into a meal themselves. This was crucial in times like the Great Depression, when people couldn't afford to waste anything. It also helped during World War II when many staple foods were rationed; wasting food was actually seen as making things more difficult for your neighbors and the country. So, aspics helped cooks use up bits of food that otherwise could have ended up in the garbage. Think of aspics as solid versions of "clean out the fridge" soups and stews.

Aspic also allowed cooks to be a little sneaky. During wartime rationing, for example, the foods that went into an aspic might be a complete mishmash simply because that's what the cook had to work with. But because aspics and Jell-O salads were already so strange in many cases, the use of food scraps really didn't matter. You could throw a party with a food-scrap aspic and the dish would still look elegant.

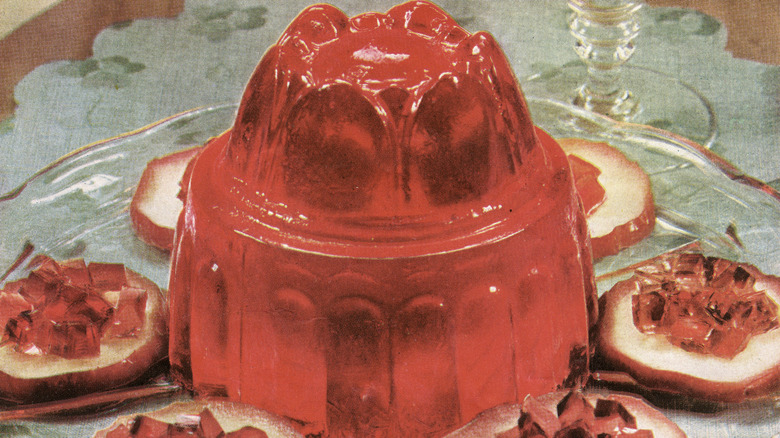

As Jell-O became more popular, aspics became more neon-hued

Aspics were originally made with gelatin that was essentially colorless. But as Jell-O became more available and more popular, it became the default gelatin for many cooks. The aspics those cooks made took on Jell-O's neon hues and fruity flavors. This had the effect of making aspic look even weirder than it already was. Instead of having, say, tuna, olives, and tomatoes suspended in a mostly clear or neutral-colored gelatin, you could have tuna, olives, and tomatoes suspended in a bright green gelatin.

At the time, this didn't seem so bad. The Jell-O provided flavor and some sugar, even though the aspics were savory, and the color certainly made aspic seem more visually interesting. But as aspics were made less and less, and more people grew up without them, those pictures of meat and eggs encased in neon gelatin towers became curiosities. That didn't help aspic's reputation at all.

Aspic's reputation became old-fashioned and snooty

After helping to extend food supplies in World War II and to provide interesting-looking recipes for dinner parties in the 1950s, aspic suddenly found itself firmly marked as old-fashioned by a lot of younger people. It was seen as something your grandparents might have eaten a long time ago when aspic was considered cool. It didn't help that younger people were encountering it in situations like family get-togethers where grandparents — in other words, the much older people in the family — were the only ones bringing these jellied dishes to the table.

Also, aspic went from being seen as the food of successful, upper-class people to simply being seen as snooty. Many Americans often see the wealthy as more arrogant than other classes, and everything those upper classes like can, by association, take on an air of arrogance as well. Anything that would have been a delicacy for the upper classes became a symbol of just how strange these people supposedly were, and aspic soon became the target of disdain.

Jell-O was later marketed as something anyone could buy

Jell-O initially made it easier for cooks at home to make aspics, but the marketing and recipe creation around aspics kept them firmly in the category of "food you want to make because elite people eat it." That is, until the marketing campaign around Jell-O switched to presenting it as food anyone could buy. Instead of being the ingredient that made those aspics look so classy, Jell-O quickly became a staple food that everyone had, regardless of their upbringing or income. What's more, Jell-O was increasingly used in desserts. That took a lot of the glamour and glitz out of savory aspic recipes.

Remember, part of the appeal of aspic was being able to have this supposedly elite, upper-class (if not royal) dish on your dinner table. Powdered gelatin and Jell-O made it easier to do that. But these were products from companies that needed to survive whatever food issues were sweeping the nation. That meant that marketing for things like Jell-O started to emphasize that cooks could use it for almost anything. That could be creating a meal while on a budget, having a dessert available that wasn't really that sugary (or that had a sugar-free version), or being so easy to use that literally anyone, including kids, could make it. But all that "Jell-O for everything" advertising meant that Jell-O was now pretty much a food of the masses, and no longer something special.

National dietary trends wanted fresher food and more convenience

Aspics were great for making meals out of scraps and all, but as the country headed into the 1960s, the national attitude toward food started to change. People wanted both fresher and more convenient food, and waiting for an aspic to gel — even with Jell-O making that process happen within a couple of hours — around food that was no longer that fresh wasn't in tune with this new outlook.

The shift toward wanting healthier, fresh food was a by-product of investigative work into pesticides and other chemicals' effects on the environment in the 1960s. As people learned more about what they were potentially being exposed to, a movement started to bring more nutrition into school lunches and people's diets in general. In the 1970s, national dietary advice from the U.S. Department of Agriculture started including more advice on getting specific nutrients, rather than just food groups.

The change wasn't immediate. You could still find cookbooks from companies like Knox and Jell-O that focused on savory Jell-O salads and other gelatinized meals in the early 1960s, but by the 1970s, efforts to limit sugar in foods, increase nutritional awareness, and provide foods that were a lot more convenient to make (especially with the influx of women into the workforce in the 1970s) led to aspics nearly fading into obscurity.

It's been making a quiet comeback for a few years

Aspic may have been the "ridiculous food du jour" in much of the U.S. during the past 50 years or so, but it's been making a quiet, unassuming comeback in a couple of ways. One is through retro cooking websites and people interested in trying these bizarre combinations that they'd heard about for so long. There are Facebook groups dedicated to re-creating these bonkers concoctions of yesteryear simply to see how weird they really are.

The other way that aspics have been making a return is through chefs purposefully working aspics (other than tomato or the meat aspic in soup dumplings) back into their menus. And these aren't bored chefs at strange diners along deserted roads; these are professionals at rather elegant restaurants simply trying out techniques that are new to a whole generation of diners. This is happening nationwide, from San Francisco to Phoenix to Washington, D.C. What's really interesting about this revival is that chefs are being open about how much effort and time these aspics take, rather than trying to make it seem like they're working magic in the kitchen. Customers have reportedly been appreciative of the skill involved. It's been suggested that diners may actually be in a great place right now to accept aspics, because they're more used to jellied and other bouncy textures in foods like boba and mochi.