The Truth About Chashu

If you've ever had an authentic bowl of tonkotsu ramen, chances are good it came with a slice or two of chashu pork. One bite of the tasty topping, and you may fall in love. Somehow, the rich flavor of this sweet and salty meat stands out in the intensely flavored environment of the creamy pork broth it's swimming in. The texture is also out of this world, a soft and silken counterbalance to the chewy noodles in your bowl. Many have called it the perfect ramen topping, but unless you live down the street from a restaurant or an Asian market, it's pretty hard to find.

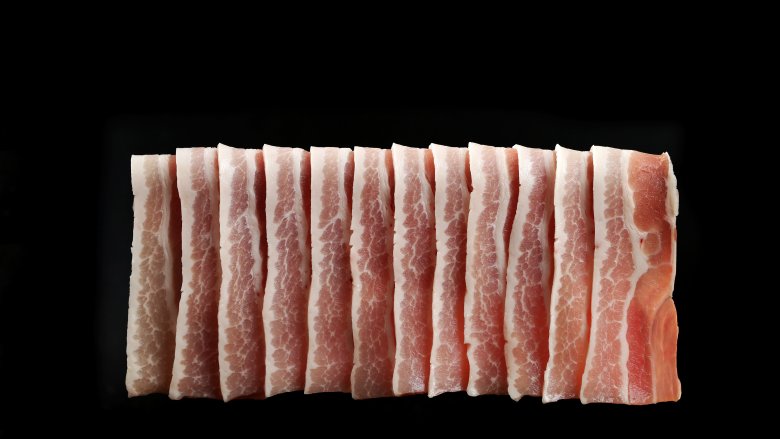

Luckily, the complex flavors of chashu pork don't come from a complicated cooking process. The ingredients list is short: pork belly (or shoulder), soy sauce, mirin, sugar, and sake. Add in some garlic, ginger, and green onions if you like, and braise the mixture for hours until the pork becomes soft and tender. Did you know this super easy way to upgrade instant ramen was that simple to make? Read on to learn what else you might be missing about this Japanese favorite.

Chashu was inspired by the Chinese dish, char siu

Some of our favorite Japanese dishes have roots in Chinese cuisine: rice, soy sauce, and chashu pork. This staple ramen topping comes from "char-siu," Cantonese sweet-and-savory barbecue pork with a chewy texture and smoky flavor. You may have seen these bright red, shiny, almost lacquered-looking pieces of pork hanging next to Peking duck in Chinese barbecue shops. Some of the ingredients are the same as chashu, but the two dishes differ in cooking techniques. Char siu always uses pork shoulder, which is marinated in a sweet sauce made from honey, soy sauce, sugar, five-spice powder, rice wine, and hoisin. It also contains an extra ingredient that creates its characteristic bright-red color. Traditional recipes used sappan wood chips, but most recipes today use red food coloring. Then, the pork is roasted or grilled over high heat until the pieces are glazed and cooked through.

Unlike its Chinese cousin, chashu is softer and more tender because it's braised in liquid instead of being roasted over dry heat. After seasoning the pork with soy sauce, mirin, sugar, and sake (usually pork belly, although some recipes call for shoulder), chashu is rolled into a log and cooked for hours until it's fall-apart tender. As it cooks, the pork soaks up the flavors of the braising liquid, giving it a rich, unforgettable flavor.

What makes chashu pork taste so good?

Pork by itself tastes fantastic — bacon makes everything taste better, and pulled pork is the cornerstone of many tasty dishes. Chashu is in a league of its own, though, thanks to the amazing science of braising. According to Fine Cooking, cooking meat at low temperatures for hours not only helps tough cuts become more tender, but it also makes them taste better, too. This type of cooking certainly takes some patience, but it's worth it when the meat gets a few hours to soak in all the flavors of the braising liquid.

But what really takes chashu to the next level is its resting period. A crucial step in creating chashu pork is to let the meat cool all the way down in the braising liquid before cutting it. We originally thought this was to make it easier to slice, but it turns out this process actually helps the meat absorb more flavor. You see, when meats are cooked low and slow and then cooled, the collagen inside the meat breaks down into a consitency that allows it to reabsorb all the flavor in the sauces. The longer it sits, the better it tastes.

Chashu is an essential component of ramen

Ramen is a pretty simple dish. At its most basic, it's just noodles swimming in a savory broth, like those packets of dehydrated noodles many of us grew up eating. If you've never had authentic ramen, you may not know how fancy these bowls can get. It becomes so much more than a soup; in fact, there are Michelin-starred ramen restaurants in Tokyo. This type of ramen has four major components: the noodles, the broth, the seasoning (also known as tare), and the toppings.

You can find a multitude of ramen toppings at a fancy restaurant, from mushrooms to bean sprouts, but the protein-based toppings are the most iconic. Chashu pork is one of the most popular of those toppings, bringing more to the bowl than just filling you up. It's all about the flavor and texture. After braising in an aromatic broth for hours, a regular pork belly becomes soft and tender, and its fat is so soft it basically melts in your mouth. It provides a perfect counterbalance to the chewy noodles, and that sweet flavor pairs perfectly with the hot and savory broth. Plus, without chashu's braising liquid, there would be no way to make ramen's second most popular topping, ajitsuke tamago (soft-boiled eggs marinated in chashu sauce).

There are rules for how to eat chashu in serious ramen shops

Believe it or not, there are rules when it comes to eating — and plating — ramen. Even the placement of the chashu pork is done in a specific, procedural way. As the Takeout explains, "there is some nuance involved" in the way the components are placed in each ramen bowl. After selecting a large bowl that can fit all your broth and toppings, add the broth and tare seasonings. Then, in go the cooked noodles, followed by the toppings (in a very specific order at different quadrants of the bowl, of course). The chashu goes in first — placed at 6 o'clock in the bowl, so it's the first thing to greet you when you receive the meal. Adding the pork first keeps it warm and lets it start flavoring the broth as soon as possible. Next up come the remaining toppings, usually an egg at 12 o'clock and any other additions at 3 or 9 o'clock. Finally, the delicate nori seaweed goes on last at 2 o'clock.

Although it went in the bowl first, you're actually supposed to wait until the end of the meal to eat the slices of chashu pork — if you can stand the wait, that is. The pork adds flavor to the broth, and the longer it sits in the bowl, the more flavorful your experience will be. The waiting is the hardest part...

Chashu recipes use either pork belly or pork shoulder

Most recipes are pretty specific when it comes to the ingredient list, but chashu pork isn't one of them. You can use one of two pork cuts when making chashu: high-fat pork belly, which is typically cured to make bacon or pancetta; or pork shoulder (often called Boston butt or picnic roast), which is usually used to make pulled pork or ham. While the pork belly has a naturally rich flavor, the pork shoulder benefits from an injection of gelatin that occurs when the collagen in the connective tissue breaks down during the cooking process, keeping the leaner meat juicy and moist.

How do you know which one to use when making chashu pork? Well, it may depend on which cut you can find at the butcher shop. Depending on where you live, it may be challenging to find uncured pork belly. But, if you have your choice, using pork shoulder results in a chewier, dryer eating experience while the pork belly creates a super soft, melt-in-your-mouth piece of meat. Certain types of ramen actually pair better with different cuts of pork, too. When eating rich tonkotsu ramen, the fattier, more juicy pork belly chashu is the cut of choice because it can hold up to the intense flavor of the thick broth. A more subtle ramen broth, like that found in shoyu ramen seasoned with soy sauce, would pair better with the pork shoulder's leaner character.

You can roll it into a log or cook it as a block

There are two ways to prepare chashu pork: rolled into a log or left alone as a block. If you're preparing chashu pork at home, it's really up to you to decide. The log-form is most popular in restaurants because they prepare large quantities of chashu every day, but it does take longer to cook. The block cooks more quickly and makes it easier to braise a single pound of pork belly, but it can dry out if you're not careful while cooking it.

When it comes to aesthetics, the rolled slices look cooler, like round little spirals in the bowl, but there's also a functional reason we prefer the rolled version. Rolling the meat slows down the cooking time by reducing the available surface area, keeping the inside of the meat as juicy as possible while it cooks. In side-by-side tests, Serious Eats found that rolled chashu lost 18 percent less moisture as compared to flat-braised pork. When the extra moisture stays inside the meat, you end up with a moist, tender piece of pork.

Rolling chashu pork is as easy as trussing up a roast

Rolling chashu pork into a log is as easy as trussing up a roast for the holidays. The major challenge with pork belly is the size difference from one end to the other. We find it easiest to start at the skinny end and roll towards the thicker end. With pork shoulder, things get a little more complicated; you'll need to remove the bone first, and you might have to butterfly the meat with a sharp knife to flatten it out for rolling. Don't worry if any of this sounds beyond your skill level; it's one of those things you can totally ask your butcher to help you with!

To roll chashu pork, simply start at one end of the roast and use your hands to roll the meat tightly up towards the other end, forming it into a large log. Secure one end by wrapping it with a long piece of butchers twine, tying it into a tight knot before moving to the other end. Then, tie the rest of the roast in 1-inch increments.

There are a few different ways to cook chashu

When cooking chashu pork, you're really looking to coax out the gelatin from the connective tissue, slowly infusing the broth (and meat) with out-of-this-world flavor. The best way to do that is by cooking a pork shoulder or belly at low temperatures for a very long period of time. According to the Takeout, there are a few cooking techniques that will get you there.

The least popular method — but the closest to the original Chinese char-siu dish — is to roast the meat in a 275 degree Fahrenheit oven for about three to four hours. The problem here is that roasting is a dry cooking technique, which doesn't give you any cooking liquid to use to cool down the chashu. Since that cooling process is critical to making the best tasting chashu pork, a better way to cook chashu is to put the pork in a pan with a flavorful liquid — traditionally, a combination of soy sauce, sake, mirin, and sugar. Then, you can roast the meat at 275 degrees for four hours and cool it in the broth.

If you happen to have an immersion circulator, you could place the pork and cooking liquid in a plastic bag and cook it in a water bath, also known as sous vide. This is the slowest cooking technique of them all — you'd need about 24 hours at 145 degrees to make this one happen — but some people say it results in the most tender meat.

You can make chashu in the slow cooker

If you love your slow cooker as much as we do, skip the fancy sous vide, roasting, and braising cooking methods altogether. The slow cooker is already designed to cook at low-and-slow temperatures, so why fuss with the oven or stove top flame settings when you don't have to? Simply set the slow cooker to low and let it do its thing.

The key here is having the right sized slow cooker for the job. You'll need to have enough room to put the entire roast (plus a few cups of braising liquid) into the bowl, so don't use a tiny slow cooker meant for appetizer dips and expect things to turn out. Next, you'll want to make sure there is enough liquid in the pot so the pork doesn't dry out as it cooks. As a general rule of thumb, we recommend using 1-1/2 to 2 cups of liquid for a 2-pound pork belly. Finally, we would advise against cooking a block chashu when using the slow cooker. It can cook too quickly if the chashu isn't rolled, leading to dry meat.

Feel free to reheat chashu using a torch

Chashu is always best if it's cooked, cooled, then reheated. This definitely requires planning ahead if you're making chashu at home, but trust us; it's totally worth it. When meat cooks, it slowly releases juices and gelatin as it hits certain temperatures. Cooling meat in the cooking liquid is always a good idea for braises, soups, and stews, allowing the meat to reabsorb many of those juices. It not only adds flavor to the dish, but it also prevents the meat from drying out. As an added bonus, cooled chashu pork is significantly easier to slice. If you've ever tried to cut room-temperature butter into perfect little cubes, you know how difficult it is to work with warm fat.

Then comes the question of how to reheat your chashu slices. You can drop them directly into your ramen broth, or you could simmer them separately in the cooking liquid, gently bringing them up to temperature while infusing the meat with some last minute flavor. When the slices are soft and pliable, they're ready to serve. But, wouldn't it be more fun to use a blow torch? It's important to keep safety in mind here — of course — but if you feel comfortable with it, you can use a regular crème brûlée torch or pick up a heavier-duty, handheld propane torch if you want to really get cooking. Then, place the slices on a piece of aluminum foil and fire up the torch. Lightly brush the flames against the surface of the pork, adding a charred, crackly layer to your chashu pork.

There are so many tasty ways to use chashu pork

Chashu pork is one of our favorite toppings for ramen, but that doesn't mean it can't be used in other dishes. If you find yourself with leftover chashu pork, or you want to try making it but it's too hot outside for ramen, think outside the bowl! Keep in mind that chashu (especially the kind made from pork belly) is very rich, so a little goes a long way. You wouldn't want to use it as a substitute in a recipe that calls for pork loin or even pulled pork. Those meats are typically less intense tasting, and using chashu could create flavor overload. But, it would make a great swap for bacon, and you can always add vinegar or tangy pickles to your meal to balance out the chashu's intense flavor.

The easiest way to use up leftover chashu pork is chashu don, a simple dish of pork belly served over steamed white rice. But, our favorite way to use it is chopped up and added to steam buns, also called char siu bao. These buns traditionally use Chinese char siu, but Japanese chashu would be a great substitution. You can also cube it up and add it to stir-fries and fried rice dishes, or thinly slice it and create sandwiches like banh mi.