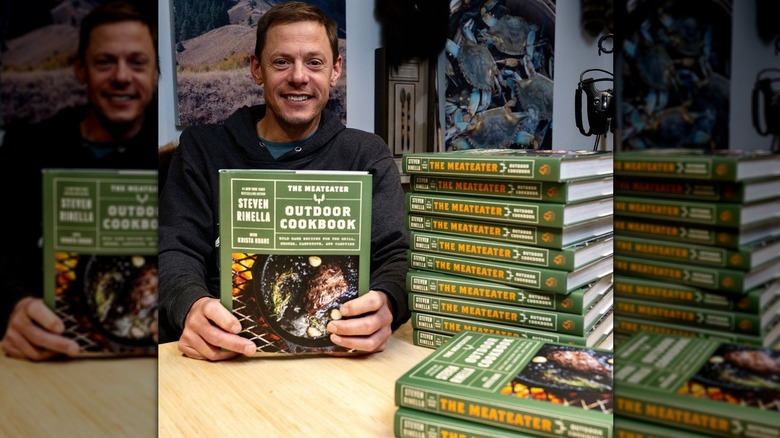

MeatEater Steven Rinella Says These Are The Tools You Actually Need For Your Outdoor Grill — Exclusive Interview

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Steven Rinella has many titles. Most often, what follows his name is "avid outdoorsman," but he's also known as a conservation activist, television personality, podcast host, and founder of the media brand "MeatEater." He's also well-regarded as an outdoor cook. No stranger to writing, these days, Rinella is leaning even further into the title of cookbook author with his new volume, "The MeatEater Outdoor Cookbook: Wild Game Recipes for the Grill, Smoker, Campstove, and Campfire."

The MeatEater's newest cookbook is as comprehensive as his life philosophy on wildlife. For those who don't hunt, it can seem contradictory to attach the word "conservationist" to the act of killing and butchering animals; however, Rinella believes and shows that hunting and conservation are intimately connected. We caught up for an exclusive interview with him, during which he shared some of his top tips for stocking an outdoor grill station, as well as how to begin working with wild game meats. Along the way, Rinella also gave history lessons on some of the more obscure recommendations in his new book.

Equipment you need for your outdoor cooking station

When you're stocking a grill station, what are some essential or underrated tools?

How about I just tell you what's in my outdoor cooking area? I think of my equipment in terms of speed and convenience. Closest to the door I have a standard Weber propane grill, which I use now and then because it's fast.

I have a deep fryer out there, which I think of as being an outdoor cooking item of major importance. We do a lot of fish frying and other stuff. I remember one time we used to live in a small apartment in New York and I had a fish fry for some friends indoors, and my wife yelled later, "Why do the bath towels smell like fried fish?" So I do like my father did and I keep my deep fryer outside.

I have a cabinet smoker that's propane-fired that does wood chips. I have a pellet grill out there and then I have an open fire cooking apparatus.

And then for tools, I'm super simple. I can do a lot of damage with a big set of tongs and a metal spatula. I have all kinds of implements and apparatuses, vegetable grill baskets and fish baskets and perforated skillets and stuff. But all in all, man, I think it's pretty simple. I tend to use mostly my indoor equipment. I don't keep outdoor equipment. When I walk out to work, I'm grabbing the same equipment I use in my home.

I do keep my fish basket and things like that outside, but for the most part, the only thing I actually store outside is wire brushes for my grills. I use my indoor stuff. I guess it's just streamlined. It's more simple. When something breaks, I'm more likely to remember and know about it. I don't like going out and seeing some greasy, rusty spatula hanging off the end of my grill. It's not my scene. I'm a little too fussy.

Unique hand tools for your grill station

What are some obscure tools that the average home cook might not have, that you think just really comes in handy?

Fry baskets for sure. A thing that most people wouldn't have is a fire bowl. It's a big welded steel fire base and it sits about waist-high and it's got an adjustable grill over it. I use it for live fires.

One could say that part of my cooking equipment includes a steel chainsaw, a splitting maul, a hatchet, and a chopping block. Because I'll do my wood up right there and split it to the dimensions I want right there. I think of that as a piece of cooking equipment, but a lot of people would not.

And for my cabinet smoker, I usually put everything away inside there. Then I have bins outside that I use to store lump charcoal. I store pellets for my pellet grill. I store wood chips for my smoker. I'll even store — seasonally — peanut oil and beef tallow out there in the area where I cook.

Are there any particular tips you could recommend for using cast iron over open flame or over grill grates?

I feel that in recent years, cast iron has become really popular. There's just been a real resurgence in cast iron use. Walk into any hardware store and you're often met with a cast iron display.

I feel like its use is spreading around faster than knowledge of how to properly use it might be. Cast iron is great because it's so forgiving over heat. It can hold a lot of heat. It can prevent you from having real hot spots on your pan that could destroy dishes. But I also think of it as ... somewhat of a fussy item in that it needs to be properly cared for.

Tips for using cast iron on your grill station

So you'd say the key to cast iron is keeping it clean?

I have a fish shack in Southeast Alaska on the ocean. We keep cast iron there and one of two things can happen. You can go up there and that cast iron will be rusty, you can go up there and that cast iron will be moldy. It comes from extremes, like being over-coated, over-seasoned, over-greased, or inadequately seasoned. I think of it as something that requires constant love. It's forgiving over the fire and it's unforgiving in storage.

When I use mine, I put it away in really good condition. If there's something stuck to it, I might scrub it off with a little bit of coarse salt. I do not use soap in it. I give it a very fine coat of oil to store it and I treat it like something that needs a lot of TLC. And if you do that, it winds up being a really good outdoor cooking implement.

When I was a little kid, we did tons of camping and a lot of outdoor cooking and it was all done on aluminum. And man, that stuff can be just a disaster to try to use over the fire, but that's what we used and it leads to tons of burnt eggs and ruined dishes. I love cast iron, but I like my cast iron because I take care of it. Other people's cast iron, I often get frustrated with.

It took me quite a long time to learn how to properly care for my cast iron pan.

Yeah. What I was saying about salt is now and then if I just need something abrasive, I might rub a little coarse salt with my thumb and then quickly rinse it off as opposed to taking a piece of steel wool or something to it.

The historical importance of cooking with bear grease

There are recipes calling for bear grease in "The MeatEater." I'm really curious about what this fat brings to the table that other sources of fat do not. And what are some of the best ways to employ it in your home cooking?

In all honesty, what it brings to the table is a deep history lesson and a skill set required in getting it, more than it brings a remarkably different flavor profile. Anything you're using bear grease for, you could substitute in pork lard. That's an honest substitution, but what you don't get with pork lard is you don't get that deep, deep lesson in ancient cooking oils.

Sure.

You go back to the Coronado expedition when the conquistadors first pushed up into the American Great Plains, and they're talking about native people's use of bear grease for cooking, as a hair dressing, as a base for dyes that are used on fabrics, a base of dyes that are used in makeup. Even before the English had ever established any colony in North America, when they were listing the potential export items that would come out of a proposed colony, they were listing bear grease.

In colonial times, people killed deer because they sold the skins and they killed bears because they wanted the lard. People know Daniel Boone, they recognize the name as a pioneer, but a lot of people don't know what he actually did for a living. Seasonally he was a bear grease hunter. He would hunt bears just to render out the lard and then sell the lard as a commodity. This item is a great throwback to our backwoods traditions.

And it's super cool because you can make it yourself. My first exposure to skinning bears and bear hunting, I wasn't aware of it. It was only until later, after I had a lot more experience, that I realized you could produce this awesome, great-tasting lard from your own black bear. And some of it is pretty phenomenal.

When you get bears that have been feeding on blueberries, that dye from the blueberries makes it into the fat and you can get fat that has a slight purplish tint to it. So it's cool like that. I love it. But I can't tell you that it's somehow superior to pork lard in taste. It's just far superior to pork lard in narrative.

How to get started with game meat

If you're somebody who's not cooked with game meat before but you're interested in getting started, what are some of the most accessible cuts and or animal proteins to work with?

First off, I'll point out that there's really no recipe in "The Outdoor Cookbook" that you couldn't replicate with domestic meats. Domestic meats are different. If we're speaking very generally, wild meat has less fat. Wild meat is capable of being tougher than domestic meat. So these are some things you have to be mindful of. There's a joke that I have with some friends of mine: "If you're having trouble cooking wild game, you're either cooking it too long or not long enough."

If you take a deer, there are parts that are really suitable for raw preparations. And there are parts that, unless you grind them or braise them for six or seven hours, are going to be un-chewable. Something that's obvious to a professional chef is that different cuts of an animal need to be prepared in different ways. It's somehow a bit of knowledge that has escaped a lot of hunters.

How has your approach to cooking game changed?

Looking back on it, we had pretty simple cooking strategies for venison. The rounds, the sirloin off the back legs on a deer, and the loin we would do as steaks and roasts and the rest of that thing we would just grind up. We didn't know that you could do a really good grilled bone-in rib chop with venison. We didn't know that you could make ossobuco with the shanks. In our minds, there were the parts that you could cut with a fork and knife, and then there were the parts you grind.

Since then, I've come to realize that you can do so much. You can do anything with wild game that you can do with domestic meat. You just have to have the will to experiment with it. It often comes down to achieving a level of tenderness with game. Sometimes that takes a bit more effort than with domestic meats. You could easily wind up with a deer that's five or six years old. When you're buying beef, you're not buying steaks and roasts off five and six-year-old cattle.

I think a great place for someone who wants to experiment, start with those whole muscle cuts that are pretty easy to deal with, that are best served rare, medium-rare. It allows you to have a quick preparation. If you take a venison loin and put some salt and pepper on it and brush it with oil and throw it on a grill to medium-rare, pull it at 125-130 [degrees F], let it sit there for a minute, slice it thin, you're experiencing the essence of venison. You can see what it's really all about. It's a really great comparison to a beef loin or a beef steak, side-by-side. With other preparations, by the time you're done, frankly, you wouldn't know that it's wild game.

Cooking with wild meats

What do you need to know about cooking with game meats?

When I was a kid, people took game because they had it. Because it was readily available. And they tried to use it to make those recognizable dishes that everybody else was making with beef. Make a meatloaf, make spaghetti and sauce, and you just throw the venison in there and you wind up with something that is indistinguishable from those domestic productions. If people are curious about game and want to experiment with it, I recommend those things that are really simple where you can find out what it actually tastes like in its pure form.

Which cut would you recommend from deer for raw preparation?

I almost exclusively do raw preparations from the backstrap. Backstrap is hunter lingo for loin and tenderloin. You can do stuff with the rounds and the sirloin, but I usually do it with that loin and tenderloin because it's just so tender. Those are definitely your most tender cuts. You can take it right off the carcass and slice it thin and it's going to have a very familiar mouthfeel to someone who's accustomed to carpaccio or tartare.

In the cookbook, you're recommending a grilled top round roast. Are there any mistakes or pitfalls that you ran into when you were learning how to grill this cut?

It's my favorite one on a pellet grill. I do them pretty hot. What I'm after really is a nice rare center and a little char on the outside. Not like black charcoal, but I like a crispy outside.

I will pretty heavily salt the exterior and I'll brush it in oil in order to get that crispiness on the outside. The reason I think it makes a great whole roast is that it has a pretty firm texture. At times you can take venison tenderloin, it can be so tender that sometimes people will eat it and they'll describe it as pasty. It doesn't have a strong enough grain when you cut it, doesn't have a steaky mouthfeel when you chew it.

But the round does. The round has a really identifiable grain. It holds together really well. In fact, so much so that if you're doing one-inch thick cuts, it's just too thick. I will do micro slices that are less than a quarter inch.

Grilling burgers from game meat

When making burgers out of lean meat, is there anything in particular that you have to avoid or really look for?

Oh, this is a controversial subject among hunters, and it has to do with whether you cut fat into your burgers. Even when you're dealing with domestic meats, when you make sausage, you're cutting in pork back fat or whatever. Now, when someone's grinding burgers at the grocery store, they're dealing with a marbled meat already. There's inner tissue fat, there's inner muscle fat, and you can make it more fatty or less fatty by putting in some of the trim as well.

Deer meat doesn't have that. Deer meat, elk meat, moose meat, any of the cervids. They don't have that inner muscle fat. If you slice a top round or bottom round, you will see there are no specks of white, there are no specks of yellow or orange. If you take a good fat round of beef and you cut it, you're going to see a lot of white inside there.

We all have our different strategies around combating that leanness. I used to be a big fan of doing 10% beef fat. I will get beef from friends who raise it, and I cut in 10% beef fat. That winds up making a burger that behaves very similarly to a store-bought burger. When I said it's controversial, that's because some purists don't want any domestic meat in their game meat at all. They might crack an egg to try to get it to bind, but they don't want any farm animals in their burger.

Other people will go in and they'll add 20% beef fat. And then you question, is that actually game meat? At what point do you have a sort of hybrid creation of wild-domestic? I'm not bothered by that question. I'll do 10% or 15% beef fat.

Using fish on your outdoor grill station

What are the most important things for people to keep in mind when grilling whole fish?

I distinguish in my mind between recipes and preparations. I think anytime you're grilling a whole fish, it is a preparation, it's a method. And in trying to explain it to someone, you're giving clues about what to look for, what you hope to see, and what you don't want to see.

As an example, the other day, my 13-year-old boy and his buddy were fishing in the creek and they caught a big rainbow trout. I was traveling for work and they wanted to cook the trout whole. And I'm trying to explain to them what the skin will look like, how easy the skin will peel away from the trout, and how its backbone will easily separate from the rest of the body at a certain point in doneness. I couldn't tell him a thing about minutes, or a thing about heat. The biggest risk in cooking whole fish is that you're going to burn it. And there are a lot of fish that just aren't that fun when they're overcooked. I love salmon, but I hate overcooked salmon.

The other risk is that you'll embarrass yourself by preparing a whole fish, inviting people over, and someone pointing out that the fish is simply not cooked and the meat is still glued to the bone and this thing's raw in the middle. How you get around that is experience.

You get around it by just looking for certain clues as it cooks. So in our preparations for whole fish you have photography and you also have a lot of mentions of things to keep your eye on. The cook needs to bring a level of awareness to it and be willing to stand over that thing and watch it and poke it and prod it and put a thermometer in it. There's no setting a timer and walking away and going and watching television, it just doesn't work.

What a beaver tail brings to the table

What should our readers know about cooking with beaver tail?

Beaver tail, again, is one of those dishes where you need to come at it with the perspective of a historian. A mountain man, historically, has a very specific definition. You're referring to people who were engaged in the Rocky Mountain beaver trapping trade of the early 1800s.

In reading about mountain men, you'll find many references to it being their favorite food. The reason it was their favorite food, most likely, is because they were eating a very fat-poor diet. If you're supporting yourself and living off of deer meat, elk meat, buffalo, particularly buffalo killed in the winter, you're not getting much oil in your diet.

But then, here's this animal that stores fat in its tail and it's an animal they're dealing with anyways. They're making their living trapping beaver and eating the meat, which is also very lean. But it has this crazy tail. And if you slice that tail open ... especially in the fall ... It's made of fat and gristle.

You need to approach it with this historical appreciation for what that meant, for how you'd have this conveniently packaged dose of fat running around out in the mountains at a time and place when you just weren't getting it. There's a term called "rabbit starvation." Rabbit is so low in nutritional value that you can starve to death eating rabbits because there's no fat. From that perspective, [beaver tail] is really fun and enjoyable.

My tip is, don't judge a book by its cover. That black scaly exterior hides an interior that is very similar to the gristle you'd find on a grass-fed beefsteak. It's a fun thing to mess with. It's a great little history lesson. When you say something's an acquired taste, that seems to be a negative, but it's a taste and texture that you need to bring an open mind to.

Steven Rinella's "The MeatEater Outdoor Cookbook: Wild Game Recipes for the Grill, Smoker, Campstove, and Campfire" cookbook is on sale now. You can purchase it here. You can also stay up-to-date with Steven Rinella at themeateater.com.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.