12 Things From Unfrosted That Are Actually True

Jerry Seinfeld's directorial debut "Unfrosted" was released on Netflix on May 3 and tells a highly fictionalized version of the origin of Pop-Tarts. Introduced in 1964, the sugary, rectangular pastry is the best of both worlds: a nostalgic breakfast treat that is still readily available at grocery stores across the country. Although Seinfeld has described most of his film as "complete lunacy," there is more than a grain of truth in the script. There really was an intense rivalry between Kellogg's and Post from their respective headquarters in Battle Creek, Michigan. It really did center on which company would be the first to release a jelly-filled breakfast pastry. And it's true that the machinations that went into Kellogg's victory did involve layers of intrigue and subterfuge.

Unlike other movies about product origin stories released in recent years, however, "Unfrosted" was made without the input of the brand it portrays and does not attempt to be historically accurate. It hasn't seemed to have ruffled any feathers, though. In an email sent to Mashed, Pop-Tarts said that it was flattered by the film. It even found a way to cash in with the help of none other than Jerry Seinfeld himself. In April, the brand announced its limited edition "Unfrosted Strawberry Trat-Pops" featuring an image of Seinfeld's "Unfrosted" character (the fictional Head of Development Bob Cabana) on the box.

The name "Trat-Pops" may be one of the movie's many inventions, but Seinfeld and his fellow screenwriters managed to sneak in the following truths.

1. Thurl Ravenscroft did create the Tony the Tiger pronunciation

If you were watching TV commercials before 2006, you probably heard the original voice of Tony the Tiger, Kellogg's mascot for Frosted Flakes. In the movie, the actor behind Tony is named Thurl Ravenscroft. Played by Hugh Grant, Ravenscroft is a petulant primadonna with an exaggerated British accent and a desperate need to convey to everyone that he spends more time speaking the words of Shakespeare than Kellogg's ad department. In one scene, he sarcastically refers to the writers of the latest commercial as "Great. Just grrrrreat," rolling the r's with maximum English drama. Ignoring the context, Seinfeld's Bob Cabana seizes on the pronunciation, and thus, the iconic Frosted Flakes catchphrase — "They're grrrreat" — is born.

Grant's over-the-top performance and the theatrical name of his character might have some viewers assuming the entire sequence is fictional, but it's more accurate than it appears. Thurl Ravenscroft was a real man (from Nebraska rather than England), and he did originate the pronunciation of the catchphrase. When he was given the script for the first commercial, he suggested extending the "r." In addition to his 50-year stint as the voice of Tony the Tiger, Ravenscroft lent his talents to several classic movies, including singing the gleefully devilish "You're A Mean One, Mr. Grinch" in "How The Grinch Stole Christmas," as well as songs in "Dumbo," "Cinderella," "Peter Pan," "Lady and the Tramp," "South Pacific," "The Jungle Book" and "Sleeping Beauty."

2. Post developed the first shelf-stable toaster pastry

The first shelf-stable toaster pastry was the result of two seemingly unrelated factors: a company-wide push to diversify breakfast and an innovation in dog food. In the 1950s, Post's parent company General Foods Corporation urged its product developers to move outside of cereal and come up with something novel. The developers obliged, creating the astronaut-friendly orange juice alternative known as Tang. Although the drink was nutritionally similar to fruit juice, it was a powder that could be stored at room temperature even after its container had been opened.

Not long after, another General Foods brand, Gaines Burgers, created a type of dog food that was partially dried and packaged in foil, making it reliably shelf-stable. Post seized on the packaging breakthrough and discovered that it could replicate the process with a partially dehydrated pastry encasing a fruity filling. The innovation eventually enabled products like granola bars, fruit rollups, and meat sticks to be pantry items rather than things that had to be refrigerated.

Unfortunately for Post, it got a little too excited about its new invention. In February of 1964, the company announced its new shelf-stable breakfast pastries, only to realize too late that it wasn't ready to market the thing. Thanks to the blunder, Kellogg's was given ample time to recreate its own version of the pastry before Post could get its product to market.

3. Pop-Tarts took a lot of engineering

"Unfrosted" depicts the invention of Pop-Tarts as zany and full of happy accidents (such as getting inspiration for the foil packaging from a pair of metal-lined hot pants invented by real-life muscleman Jack LaLanne), complete with a who's-who panel of 20th-century inventors and a talking ravioli. In reality, it was a lot less colorful and star-studded, but no less complex.

To create its famous product, Kellogg's enlisted Air Force veteran Bill Post (no relation to Kellogg's rival corporation), a well-known food manufacturing guru who was running a plant for Keebler Food in Grand Rapids. Kellogg's originally approached Post to see the equipment at his plant, explaining that it wanted to create a breakfast food for the toaster but had only managed to come up with a cracker-like sheet of dough.

Bill Post had to figure out how to make two sheets of dough with filling in between. "We had to put a sheeter over another sheeter, so a 60-ton piece of equipment had to be raised on a platform," he explained to Kalamazoo affiliate WMMT in 2021. "[G]uys at the bakery thought that was crazy." The process took months. The frosting, on the other hand, only took a day, even though Post's colleagues were sure it couldn't be done. In the end, Post's reputation as a food engineering genius proved correct: the sugary formula did not melt in the toaster as his coworkers feared.

4. The rivalry was very real

As far as we know, there was no mafia-style cabal of milkmen forcing Kellogg's employees to run for their lives through a sea of cow manure, but the rivalry between Post and the eventual Pop-Tarts manufacturer was even more entrenched than the movie lets on. In fact, it went back much farther than the breakfast pastry war, and even farther back than Kellogg's itself.

In the late 19th century, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg was a medical director at the Battle Creek Sanitarium, a health clinic that promoted an alternative approach to wellness through exercise and diet. Hoping to provide his patients with healthier breakfast options, Kellogg created cornflakes, only to discover in 1895 that one of his former patients, C.W. Post, had started selling a nearly identical product under his own name. In an attempt to reclaim his invention, Kellogg started a rival company a decade later. Within a handful of years, Kellogg's (then called the Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company) was selling more than 100,000 boxes of Corn Flakes a day.

The companies' headquarters were so close that, in the 1920s, executives could count the number of boxcars ferrying merchandise out of each others' warehouses. Given this fraught origin story, it must have seemed like poetic justice when Kellogg's co-opted Post's innovation in 1964 and became, for many, the maker of the definitive toaster pastry.

5. The inventor of sea monkeys was a Nazi sympathizer

One of the more bizarre plot points of the movie is its subplot spoof of the Space Race. Arguing that the only way to beat Post is by enlisting the most innovative, unconventional minds of the 1960s, the Kellogg's development team brings together a panel of forward-thinkers, including bicycle-maker Steve Schwinn, fitness entrepreneur Jack LaLanne, soft serve ice cream pioneer Tom Carvel, Sea Monkeys inventor Harold von Braunhut, the mustachioed cooking legend Chef Boyardee, and the fridge-sized computer known as UNIVAC. Called the Taste Pilots, these fictional versions of famous figures are tasked with creating the perfect breakfast pastry.

This entire subplot is, not surprisingly, pure fiction. However, the characterization of at least one of the Taste Pilots is not so far off the mark. In the movie, Harold von Braunhut speaks with a thick German accent and makes subtle allusions to right-wing ideology. In the real world, von Braunhut was a passionate white supremacist who posed in front of a Nazi flag and was a committed member of the Aryan Nations hate group. In 1988, it was revealed that a portion of the profits from his minuscule wrist weapon, the Kiyoga Agent M5, went directly to the leader of the Aryan Nations. If anything, von Braunhut in the movie is less extreme than he was in real life.

6. The Soviet Union did play a role in the U.S. sugar supply chain

As the Breakfast Wars escalate in the movie and Post prematurely declares that its new pastries are ready to hit the market, Bob Cabana and his colleague Stan (Melissa McCarthy) decide to do something drastic: cut off Post's sugar supply. Flying to Puerto Rico, they make a deal with the head of the sugar industry (who bears more than a passing resemblance to Pablo Escobar) to purchase his entire supply at a premium. In response, Marjorie Post (Amy Schumer) decides to travel to Moscow and asks Nikita Khrushchev to sell her company sugar from Cuba. While there is no factual basis for this part of the movie, the truth is that the Soviet Union did play an antagonistic role in disrupting the U.S.'s sugar supply chain.

Before the Cuban Revolution in 1959, the U.S. accounted for 70% of Cuba's trade, mostly in the form of sugar. As tensions between the countries spiraled in the early '60s, however, the U.S. canceled sugar shipments from its former trading partner. Seeing an opportunity to strengthen its ties with Latin America, the Soviet Union stepped in to pay the difference, rescuing Cuba's floundering economy and further inflaming its own relationship with the U.S. The Soviets may not have been purchasing Cuba's sugar on behalf of Post, but they did purchase a sizeable amount of it.

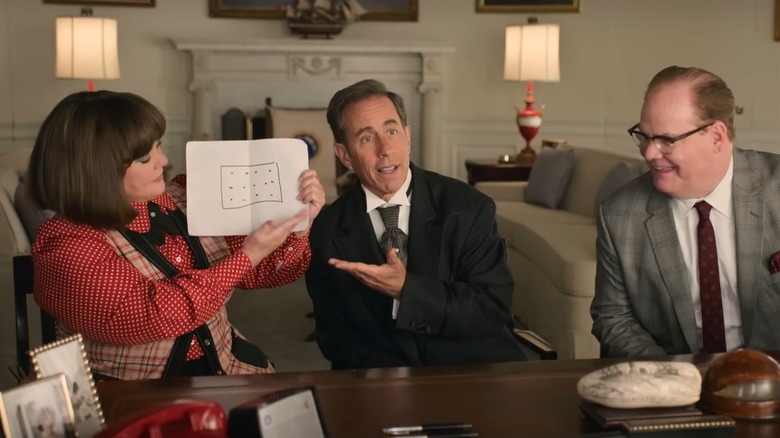

7. Executives did make the Andy Warhol connection

The movie freestyles the naming process of Pop-Tarts, imagining a brainstorming meeting in which Melissa McCarthy tosses out names such as Fruit Magoos and Oblong Nibblers before settling on the acronym for "toaster ready anytime treat, put on a plate" (Trat-Pops). The eventual shift to Pop-Tart arrives when legendary TV anchor Walter Cronkite loses his notes on the product during a live broadcast. "Isn't Pop-Tart a little too close to Andy Warhol's Pop Art?" McCarthy's character asks. "Nobody will make that connection," Seinfeld's character retorts.

In real life, that connection was the whole point. After discarding the original (and highly forgettable) name of "Fruit Scones," Kellogg's executive William LaMothe alighted on Pop-Tart thanks to his appreciation for the era's Pop Art movement. The association was a savvy move since it immediately aligned the humble breakfast product with one of the most popular and modern artistic movements sweeping the U.S. and the U.K. The brand took its ultra-modern approach even further by releasing four original flavors — Strawberry, Blueberry, Brown-Sugar Cinnamon, and Apple-Currant — and dubbing them the "Fab Four" in reference to the Beatles.

8. Children were used as taste testers

No one will be shocked to learn that Kellogg's did not, in fact, get the idea for Pop-Tarts when one of its executives spied two kids dumpster diving for discarded pastries in Post's backlot. It got the idea when Post made the announcement that it had developed jelly-filled, toaster-ready pastries. The recurring presence of the kids in "Unfrosted" might therefore seem like a clunky plot device, but the scene in which they're given a sample of the unreleased treat is partially accurate.

Before Pop-Tarts were released, Kellogg's enlisted a small army of children to test them, including Bill Post's own offspring. "I used to bring a lot of stuff home ... and they'd turn up their noses," he told Midland Daily News in 2003. "[T]hey didn't like this or that. But they used to ask me, 'Bring those fruit scones home.'"

Aside from the Post household, families in certain parts of the country were selected to help develop new flavors. One participant recalled that the pastries were delivered to her family's home in a cardboard box with only a number to indicate the iteration of the recipe (via The New York Times). Kids as young as kindergarteners were tasked with filling out forms to judge the pastries on texture and flavor. They may not have played an integral role in the naming of the product as they do in the movie, but they did help determine which flavors made it to grocery store shelves.

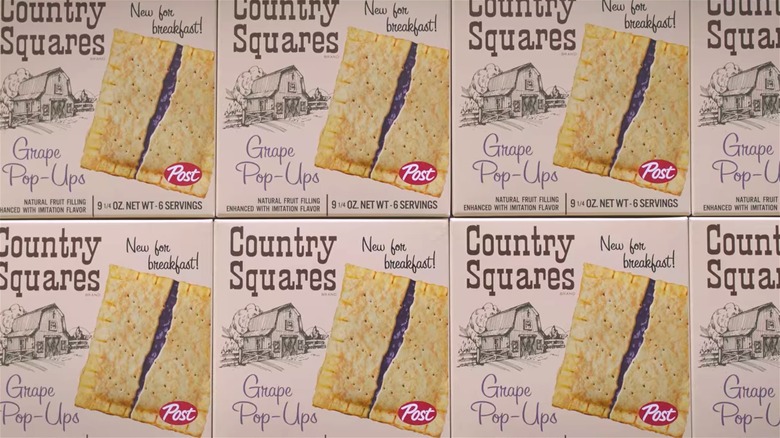

9. Post did struggle with branding

"Unfrosted" is less than charitable toward Post's marketing of its new breakfast pastry. When the grocery stores are sold out of Pop-Tarts but have plenty of its competitor's product, Country Squares, left behind. The head of Kellogg's, Edsel Kellogg III (Jim Gaffigan), theorizes, "It's the name. No kid wants to be a square. And a square from the country? Forget it." In comparison to Kellogg's cutting-edge reference to the Pop Art moment, a product evoking the countryside and prudishness was the last thing kids in the '60s wanted to be associated with.

The stark contrast in marketing isn't just a fabrication in the movie. When Post announced that it had created a shelf-stable breakfast pastry in 1964, it did, in fact, dub the product "Country Squares." While this might not have been the determining factor in its failure, it was a misstep that the company came to recognize. By 1967, it had rebranded the product to the embarrassingly derivative yet somehow much worse name "Toast-Em Pop-Ups." Meanwhile, Pop-Tarts was playing offense, taking out full-page ads in local newspapers and appearing in commercials during the most popular TV shows of the era including "Beverly Hillbillies," "My Favorite Martian," and "What's My Line."

10. Pop-Tarts did sell out quickly

In the movie, the day that Pop-Tarts are introduced into stores is nerve-wracking for the Head of Development, Bob Cabana. The company's phone lines are down and he and Edsel Kellogg III are unable to get updates on the sales numbers. When someone finally gets through to them, it turns out that the product has been even more successful than they could have hoped. "Every store in the continental U.S. was cleaned out within 60 seconds," Kellogg says, adding, "Kids are doing anything to get their hands on these Pop-Tarts. Six stock boys were bitten. It's a feeding frenzy."

The newly launched product didn't sell out in 60 seconds (nor were there reports of supermarket employees being assaulted by elementary school children), but it did sell out quickly. Within two weeks, store shelves were empty. In yet another savvy marketing move, Kellogg's released an ad apologizing for the popularity of its hit product, saying that a new and improved version would be back in stock soon. As intended, this only served to heighten the demand for the pastries.

11. The mascots are real

"Unfrosted" is full of outlandish subplots, from the mafioso milkmen to the dumpster-diving kids. One of the most far-fetched is the mascot rebellion that threatens to interfere with the launch of Pop-Tarts. Under the leadership of Thurl Ravenscroft, who has grown increasingly disgruntled with his employers ever since Cabana refused to provide a cooling unit inside the head of his lion costume and dismissed his plans to stage "King Lear" in the food lab, the iconic food mascots go on strike. As the executives argue over the naming and marketing of the new product, a sea of mascots assemble at the entrance of Kellogg's headquarters, growing increasingly threatening.

The mascot rebellion is fictional, but the writers of "Unfrosted" wanted to keep at least one aspect of the subplot true to life. "Almost everything is identical to the way it was in the '60s," co-writer Spike Feresten revealed in an interview with Eater. "Tony the Tiger is the 1960s Tony the Tiger, and so is the Cornelius [Rooster, of Corn Flakes]. Everything wrapped around the movie — the set design, the set decorating, the logos — is all hyper accurate, with a few exceptions ... That part of it is very, very accurate."

12. Marjorie Post did build Mar-a-Lago

If there is an out-and-out villain in "Unfrosted," it's Amy Schumer's Marjorie Post, the president of Kellogg's rival and a gleefully nasty employer. Whether she's shooting elastic bands into the eyes of her minions or knocking them out with a swift typewriter to the head, she oozes malevolence from every pore. The movie doesn't make many claims of historical accuracy, but at the end, a voiceover reveals what happened to the characters. Most of it is fictitious. For instance, Thurl Ravenscroft was not dragged before Congress and Chef Boyardee and Harold von Braunhut did not move in together and raise their sentient ravioli love child. However, one claim is accurate: Marjorie Post did build the Palm Beach resort known as Mar-a-Lago.

Post was one of the first female chief executives in the country and was one of the nation's wealthiest women during her lifetime. She spent about $7 million on the estate (over $90 million in today's currency), which was completed in 1927. It had 58 bedrooms, 33 bathrooms, a 1,800-square-foot living room, and gold-plated fixtures throughout (which Post insisted made them easier to clean). The cereal heiress intended to eventually donate the property. Yet, the Smithsonian, the state of Florida, and the U.S. government all declined to accept such a donation due to the astronomical sum required to maintain the estate. Eventually, it went on the market for a mere fraction of its original price.