Where Did Steak Come From And How Has It Evolved Through The Years

You could travel all over the world and find steak on the menu. Steak is so ingrained into our diets that you might assume we've eaten it forever — and we kind of have. Humans have consumed beef and game meat since prehistoric times, but the concept of steak didn't catch on until more civilized, albeit ancient times. When we think about steak's origins, we also must consider how European colonization and economic shifts have affected humankind's relationship with beef consumption and the cattle that supply the meat.

The term steak refers to how the meat is cut and how it's prepared. The meat is cut across the animal's muscle in thick sections and cooked at high heat, on a grill, or over an open flame (like a spit or a gas stove). This differentiates steak from roast beef, which gets the low and slow oven treatment. If we quantify steak only by its cut, the meat can come from different animals (think ham steak or swordfish steak), but describing meat simply as "steak" refers to beef.

If you're looking for a timeline of how steak has evolved over the years, you've come to the right place. What started as a large cut of meat and some fire, became a culture and a cuisine. From open-air grills to white cloth dining tables, takeout windows, and beyond, we're exploring the history of steak, its longstanding relevance in society, and where it's headed in the future.

Steak as we know it comes from Europe

Mentions of steak as a culinary concept date back to the 1400s. In Scandinavia, historical records from this period refer to thick cuts of meat from an animal's hindquarters as "steik", "stickna", and "steikja". In England, cooks of the Middle Ages were writing down their recipes. One of these recipes was "Stekys of venson or bef" which called for the grilling of sliced meat. Yet, the dish closest to modern-day steak originated in Florence, Italy during the Renaissance.

It was about 1565 when the Florentines established the Day of St. Lawrence on August 10th, an annual feast named to honor a Roman martyr who was reportedly tied to a grill and burned circa A.D. 258. Likely inspired by the gruesome nature of St. Lawrence's death, the holiday was celebrated by cooking large quantities of sliced meat, or "bistecca", on open-air, coal-fired grills. It is believed that English merchants who were present at the Day of St. Lawrence anglicized the word "bistecca" into "beefsteak", or "steak" for short.

Centuries later, Bistecca alla Fiorentina (a.k.a. steak Florentine) remains an essential dish of Northern Italy. An authentic version of this large, charcoal-grilled steak (T-bone or porterhouse cuts are typically used), is made with beef from Chianina cattle, one of the world's largest and oldest cattle breeds. Chianina are prized for their high-quality meat and have been raised in Tuscany for over two thousand years.

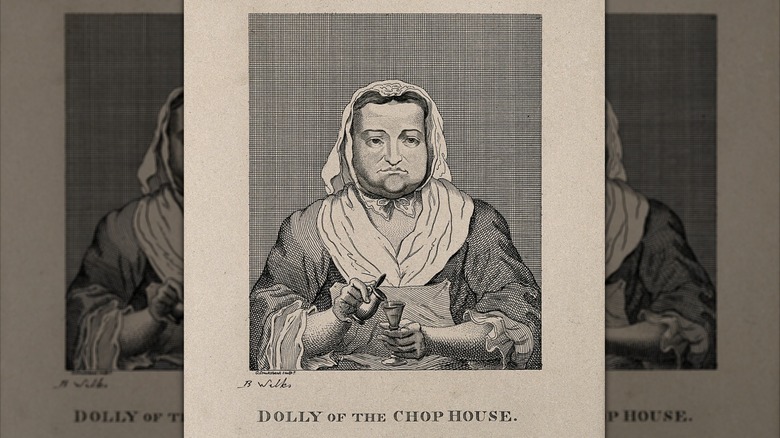

Before the steakhouse, came the chophouse

England has been at the forefront of steak culture from the beginning. Recipes for venison or beef steak were recorded as early as the 1400s, and by the late 1600s, chophouses were popping up in London. Today, a chophouse eatery often indicates a steakhouse that's a little rustic but still high-end. This sense of refinement was utterly absent at the original chophouses.

The purpose of the earliest chophouses was simple: feed workers a hot meal. Back in the Middle Ages, eating beef was a sign of wealth in England, but by this time, it was lunch for the average working man. In the early days of the chophouse, there was no need for a menu — one kind of meal was served each day, usually at a specific time. Since feeding local workers was the goal, the first chophouses did not serve women. There was no ambiance, just communal tables for men to grab a seat, get some sustenance, and return to the job. These kinds of meals were known in England as "ordinaries".

As time went on, England's chophouses began to take on a more restaurant-like appearance. In the 1700s, restaurant culture was catching on in nearby Paris. Sitting at a cafe table and ordering off of a printed menu was becoming the European fashion, and although chophouses mostly stuck to unfussy steak dishes, meal options and meal times lost their initial rigidity.

The American cowboy steak has a Spanish influence

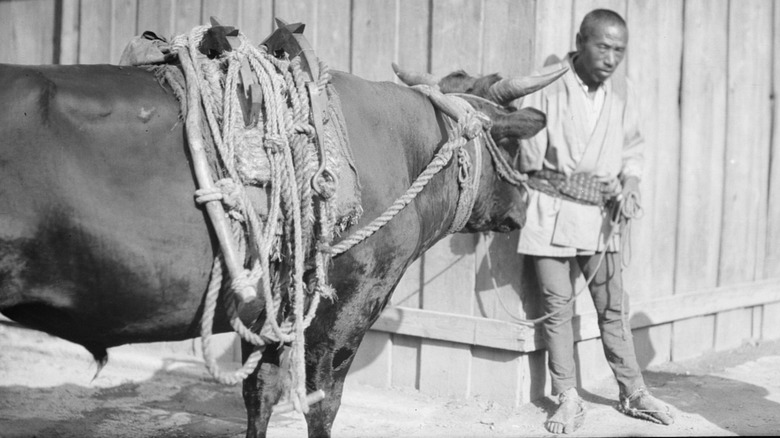

Steak comes from cows, but where do cows come from? Hint: not America. Many studies have been conducted to determine where cows first lived before being shuffled around the world. This meant tracking down the origins of an ancient cow species called auroch. The auroch were huge, wild cattle that were powerful and difficult to domesticate. Scientists have traced their lineage back to regions of the Middle East, Eurasia, and Northern Africa. Aurochs have been extinct since 1627, but smaller descendants of the species touched down on American soil in the 1500s. How did they get here?

Spanish colonists brought domesticated cattle along on their expeditions to the Caribbean. The presence of livestock spread throughout Central and South America, and eventually Texas. A mix of three Spanish cattle breeds make up the ancestry of what would become the Texas Longhorn.

Without the Spanish influence on the New World, cowboy culture would not exist. Vaqueros ( Spanish for cowboy) in Mexico were the inspiration for the American cowboys who wrangled cattle in Texas and later, the West. Since they were responsible for driving cattle throughout the nation's expanding territory, American cowboys didn't eat steak every day — but when they did, they butchered the meat themselves. They favored simple, hearty cuts of ribeye cooked over the open flame of cast iron grills. We still refer to this cut as cowboy steak.

Steaks transitioned from frontier food to fine dining in the 1800s

The Transcontinental Railroad, built between 1863 and 1869, made transporting cattle (and steak) to different parts of the country quicker and easier. Steak became more accessible in urban areas, where its culinary prowess was evolving beyond its outdoor grilling roots. Even before the Transcontinental Railroad was complete, New York City was home to the first modern steakhouse in America.

Delmonico's didn't need the Transcontinental Railroad to get established. The restaurant opened in 1837 in Manhattan's Financial District. Taking a cue from the restaurant format popularized in Paris, Delmonico's was the first fine-dining eatery in the United States. Delmonico Steak became a signature dish. In the early days, the cut of a Delmonico Steak was at the butcher's discretion. As time went on, a tender, thick cut of boneless ribeye was the standard. This storied steakhouse was closed for three years after COVID-19 hit, but reopened in August 2023.

Delmonico's became a celebrity hotspot pretty early on (check out the photo of Mark Twain having his birthday dinner here) yet soon enough, other N.Y.C. steakhouses began to open. The Old Homestead Steakhouse debuted in 1868 and Keens Steakhouse came around in 1885. Both restaurants remain in business today.

Asian cultures were slower to embrace steak

Some of the steak dishes coming out of Asia are so highly sought after, and it's hard to believe that Asian steak culture is a relatively new phenomenon. Mashed spoke with writer Mark Schatzker author of "Steak: One Man's Search for the World's Tastiest Piece of Beef" to learn more about steak's history in the East. "The Japanese ... renowned for their superbly marbled wagyu beef, have only been raising beef cattle seriously for less than a century," Schatzker explained.

Eating beef in Japan was almost unheard of until the Meiji period when the culinary influences of foreign traders took the nation by storm. Emperor Meiji himself started eating beef in the 1870s. Japanese people also believed that beef consumption improved their physical strength.

And then there's wagyu. According to Schatzker, "Unlike most breeds of cattle, wagyu have truly distinctive genetic traits that affect the eating experience. They marble incredibly well, and the fat has more monounsaturated oleic acid, which gives it a lower melting temperature and sweet taste. These traits are best expressed when wagyu cattle are raised slowly and processed after their second birthday."

In South Korea, thinly sliced, marinated beef has been eaten since the Joseon dynasty (beginning in 1392), however, it was reserved for royalty back then. Bulgogi beef (which translates to fire meat) started popping up in restaurants in the 1920s. Today, Korean barbeque spots enjoy widespread popularity in the U.S. and beyond.

Fried steak dates back to the early 20th century

By the 20th century, steak was entering its boundary-pushing era. Frying steak rather than grilling or spit-roasting started gaining popularity in the early 1900s. A dish like country-fried steak sounds all-American, but like most U.S. foods, it's cross-cultural.

Recipes for deep-fried steak — also called chicken-fried or country-fried steak — have graced cookbooks since the early 1900s. Fried steak dishes are known by many different names depending on where you are in the world, but it was likely German and Austrian immigrants arriving in Texas between 1844 and 1850 who inspired country-fried steak in America.

Country-fried steak bears a lot of similarity to wiener schnitzel, a pounded veal cutlet, that is breaded and fried. Wiener schnitzel is a hallmark dish of Austria and Germany, but to contend with the more affordable, tougher cuts of beef sold near ranching communities in Texas and Oklahoma, veal was swapped out for lesser-quality beef which could be tenderized by pounding. The steak version of the dish was a huge hit.

Yet, no country-fried steak is complete without its rich gravy. White gravy is commonly used, and its roots are distinctly Southern. The details of country gravy have been subjected to much debate, but it is widely believed to have originated in Southern Appalachia in the 1800s.

The Great Depression era gave us cheesesteaks and the steak burger

During the Great Depression, many American families struggled to keep food on the table. Meat and other household food staples were expensive and the goal was to make a little go a long way. Getting creative with scraps that might have been thrown away in rosier times was the new normal. It was also the beginning of what would be a true icon of the American food scene: the Philly Cheesesteak.

Pat Olivieri invented the cheesesteak in Philadelphia in 1930. Olivieri operated a hot dog stand in South Philadelphia. Looking to fix himself something different for lunch he bought some beef scraps from a nearby butcher shop, grilled them with some onions, and placed them inside a roll. Olivieri shared the sandwich with a local cab driver who insisted it was superior to hot dogs. The hot dog stand became Pat's King of Steaks, a longtime landmark of the city.

Over in Illinois, a married couple named Gus and Edith Belt decided to turn their struggling gas station into a restaurant. During the Great Depression, some burger joints advertised steak burgers, which contained higher-grade beef than basic hamburgers. The Belts saw potential in the idea and started selling steak burgers under the restaurant name Steak 'n Shake. Today, there are more than 400 Steak 'n Shake locations in the United States.

Steak with sauce was all the rage in the 1950s

The 1950s was brimming with food trends, and for good reason. World War II rations were over and the economy had improved. The decade also saw the expansion of cattle feedlots in America's midland, which ensured that the growing demand for steak could be adequately supplied. Steak with sauce was having a major moment. Classic European dishes like steak au poivre and steak Oscar weren't brand new in the '50s, but they were experiencing renewed popularity and are now considered fine dining steakhouse staples.

If there had been social media in the 1950s, you better believe steak Diane would've had a viral moment. Steak Diane was soaking up the limelight on account of its exciting tableside presentation. A filet mignon pounded thin, was cooked in a pan, and doused in a luxuriant sauce of mushroom, butter, beef jus, Dijon mustard, and Cognac. Just before serving, steak Diane was flambéed at the table, much to the delight of high-society diners.

Not all the steak and sauce dishes popular in the 1950s hailed from big cities. Steak de Burgo originated in Des Moines, Iowa. Featuring a filet with creamy garlic sauce and Italian herbs, steak de Burgo became a Midwestern classic. Within the home, Salisbury steak was getting a mid-century modern makeover. The budget-friendly hamburger steak with mushroom gravy was among the earliest T.V. dinners.

Like any popular food, steak can get weird

To find out more about steak's international popularity, we asked Schatzker about the progression of steak culture. "Historically, many countries that raised cattle were oriented towards dairy production and veal," he said. And although cattle raising has been a centuries-long practice, Schatzcher noted that "much of the steak culture we know and love is comparatively recent."

Over time, chefs have prepared steak in new and inventive ways, which sometimes fostered an environment for weirdness. Take carpetbag steak for instance. This boneless rib-eye stuffed with oysters is a funky version of surf and turf. Carpetbag steak's origins are murky, but it is often associated with mid-century Australian cuisine.

Then there's steak tartare. This dish of raw beef topped with a raw egg is the epitome of an acquired taste. Steak tartare as a concept has been traced to the eating habits of ancient Mongolian warriors, however, steak tartare's refinement occurred in France. Steak tartare is definitely old-school, but it's still served at fine dining establishments.

Then steak became huge

Cowboy steaks were an emblem of the Old West, but what about tomahawk steak? The tomahawk steak takes its name from the large cuts of buffalo meat Native American tribes of the past consumed. The long bone inside this ribeye cut resembles the handle of a Native American tomahawk.

Yet, tomahawk steak cuts didn't go mainstream until the 1950s. By then, the steakhouse scene was moving beyond the stiff traditions of formal fine dining and began flirting with steak's role in the American Wild West. Chefs (and diners) favored the tomahawk cut for its large size, well-marbled meat, and the dramatic length of the ribeye bone.

Tomahawk steaks are still popular at many steakhouses, but the sheer size can be a little intimidating. Tomahawk steaks for two are also popular, including those made from coveted wagyu beef. Empire Steakhouse, a small New York City chain, sells a wagyu tomahawk for two wrapped in 24-karat gold — which will currently set you back $495.

The demand for leaner meat inspired select grade beef

In today's health-conscious world, a huge portion of fat-marbled steak is not how everyone wants to approach dinner. In fact, in the 1980s and into the '90s, demand for leaner steak grew. In the United States, federal beef-grade standards have been in effect since 1927, but it wasn't until 1987 that a new grade of steak — USDA Select — came into prominence.

As health consciousness grew, red meat consumption waned, but USDA Select allowed consumers to enjoy steak without guilt. USDA Select was thriving, yet the biggest criticism was that this leaner form of steak lacked flavor. Since the Select grade focuses on cutting away the fat, it misses that tender, juicy taste that the fat marbling of say, a USDA Prime Grade.

Select beef may not yield a decadent steak, but the USDA designation is a literal stamp of quality. This makes it a popular buy in grocery stores. Lean steak can be versatile — it's great in a salad or as steak tips — but if you're looking for an indulgent steak moment, select will likely underwhelm.

All-American steakhouses have company

For so long, steakhouses in America were pigeonholed into an austere fine dining atmosphere or a casual, family-oriented eatery that paid homage to the American West. At the former, you could expect elegance, haute cuisine plating, and, of course, higher prices. The latter offered decent steak and decent prices, but not much else. Nowadays, there are more options.

After a near century of Americanizing steak, the cultural ties to what made this dish so beloved in the first place are staking a real claim in the restaurant industry. Not only are many chef-centric steakhouses bringing in sauces and flavors that go beyond the European de rigueur, but steakhouses like Fogo De Chão are experiencing success in the U.S.

Fogo De Chão is an authentic Brazilian steakhouse chain that introduced all-you-can-eat steak to mainstream America in a way that rattles our previously conceived notions of mediocre steak at budget buffets like Sizzler and Ponderosa. At Fogo De Chão, "churrasco", Portuguese for barbecue, is the main event, but fine dining touches like tablecloths and cocktails are part of the experience. As of now, Foge De Chão operates over 70 locations around the globe.

In the modern age, sustainability is key

As our food processing methods continue to strive toward the most sustainable methods possible, it's easy to wonder how factory farms and feed lots known for processing mass amounts of cattle into beef can do better. Beef sustainability is the priority on many American farms, but perhaps not enough. What does the future of beef sustainability look like?

"My hope is that it's headed towards more pasture-based, regenerative production methods," Schatzker says. "Grass-fed beef has a deep and resonant flavor profile that cannot be equaled by grain-fed beef, in my opinion. Cattle also have the ability to turn plants that grow on marginal farmland—grasses and forbs—into nourishing food." But maybe it's not as simple as it seems.

Schatzker goes on to say that, "Managing pasture doesn't require fossil-fuel-based fertilizers. But raising cattle on grass is more like winemaking — both a science and an art. We've come a long way since I wrote Steak, and I'm more excited than ever to see, and taste, where we are headed."