What You Didn't Know About Butter

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Our love for butter can't be disputed. Statista reports that in 2022, the average American consumed 6 pounds of butter, an increase from the 4.5 pounds per capita eaten just before the turn of the 21st century. While we all know butter as an indispensable kitchen staple, not as many of us are aware of what the yellow spread consists of and how it's made. For such a ubiquitous product, many of us are also unfamiliar with butter's intriguing origins and history.

Butter has been an important part of the human diet across different civilizations for thousands of years. At its most basic, the creamy dairy product consists of just three ingredients: butterfat, milk solids, and water. Relatively simple to produce, butter is believed to have been discovered by accident when milk was agitated during transport, leading to the formation of the kitchen staple. Over time, butter has evolved into a versatile ingredient used not just as a spread, but also added to countless recipes worldwide, from French croissants to Indian butter chicken.

Eager to delve deeper into the fascinating world of butter? Take a look at our collection of fascinating facts about this culinary must-have!

Butter has a long and fascinating history

For an everyday product that often gets taken for granted, butter has fascinating origins. This ubiquitous yellow spread, which has been in existence for about 9,000 years, was probably stumbled upon entirely by chance. It's believed that ancient nomadic people would transport milk in sacks during their travels. The swaying motion of their pack animals probably churned the milk into butter. Remarkably, one of the earliest documented records of butter-making can be traced back to a 4,500-year-old tablet, a relic from the Sumerian people of Mesopotamia in the area of modern-day Iraq.

Butter became popular in Europe in the Middle Ages, when it was commonly eaten by the lower classes. Interestingly, the dairy spread was often used as a levy. For instance, in 12th century Norway, the king would demand a bucket of butter as the annual tax contribution from his subjects. In 15th century France, the Catholic church enforced a ban on butter consumption among its followers during Lent. Cleverly, the church also gave its congregation the option of paying a levy to have the butter ban lifted. The number of Catholics who chose to pay the butter tax was so high that the money raised was used to add a tower to France's Rouen Cathedral, today also referred to as the Butter Tower.

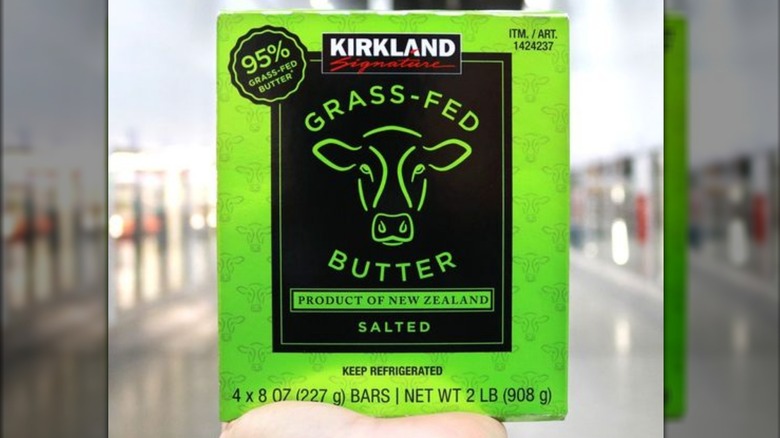

There are many different types of butter

Most of us are familiar with two types of butter: salted and unsalted. Unsalted butter is normally used as a spread and in general recipes that call for butter, as it lets chefs easily control the salt content of their final product. Meanwhile, salted butter isn't normally used in cooking. Instead, the condiment, which was historically salted for preservation purposes, is often used as a spread to enhance the flavor of bread or crackers.

Besides salted and unsalted butter options, there is a plethora of other butter types, each distinguished by its own flavor, texture characteristics, and culinary applications. One such variety is the creamy and rich-flavored European-style butter known for its high butterfat content, which generally ranges from 82% to 90% compared with the standard 80% found in American butter. Whipped butter, on the other hand, has air stirred into it, making it lighter and more spreadable than traditional butters. One of the stronger tasting butter varieties is cultured butter. Not for everybody, cultured butter is fermented, a process that gives it its distinctive tangy flavor.

Butter isn't only made from cow's milk

The belief that butter is exclusively made from cow's milk stems from its widespread availability on supermarket shelves. In Western culture, cows have been the primary source of milk and dairy products due to their placid nature and plentiful milk production. Additionally, unlike milk from other animals, cow's milk is flavorful but not overpowering, which lends itself well to butter making. However, in reality, cow's milk barely scratches the surface of possible butter sources.

Historically, butter was made from the milk of a variety of domesticated animals including sheep, goats, yak, and even camels and buffalo. In fact, the first butter was likely made from sheep milk or goat milk since those — and not cows — were the animals that were domesticated when butter entered the scene thousands of years ago.

While butter made from the milk of animals other than cows can be tricky to find today, it definitely does exist. So what does butter from these alternative sources taste like? Hanson O'Haver from My Recipes interviewed Elaine Khosrova, author of the book "Butter: A Rich History." Khosrova describes sheep butter as gamey and somewhat greasy, yak butter as very mild and less sweet than cow milk, and water buffalo butter as very flavorful and a little tangy. When it comes to goat milk, one customer reviewing it calls the taste interesting, adding that it "was similar to regular butter but had more of a sweetness and creamier taste to it."

Butter comes in different colors

Rather than being uniform in color, butter can range from white to deep yellow. The color of butter is largely influenced by the diet of the cows that produce the milk from which it's made. The hue of the kitchen staple can also be the result of the season in which the butter is produced and the specific production practices.

Butter made from the milk of cows fed on hay or grain tends to be pale in color, leaning toward a light yellow or white. This is the kind of butter we usually get in the U.S. In contrast, cows that graze on green pastures tend to produce milk with higher beta-carotene content, which imparts the butter with a deep yellow hue.

Butter produced from the milk of grass-fed cows tends to be more yellow when the dairy is collected in the warm months of late spring or summer when the cows feed on grass that's at its richest in beta carotene. Additionally, some manufacturers may dye their butter deep yellow with natural colorants, such as annatto, to make the products more appealing and consistent to consumers.

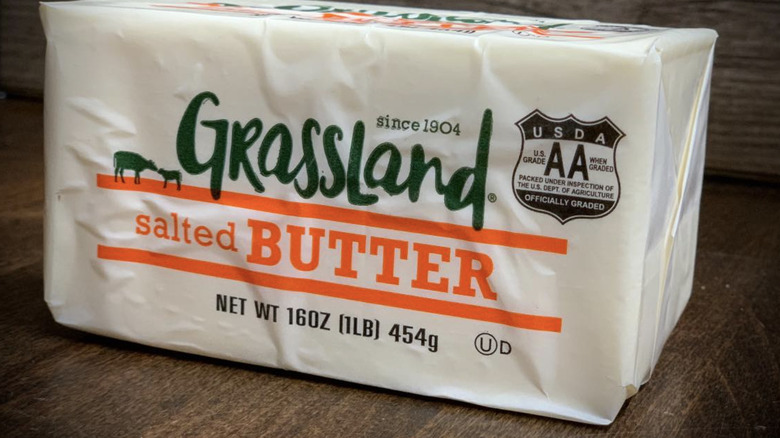

USDA divides butter into three grades

Butter can vary in quality, which can greatly affect its taste and consistency, as well as the culinary outcomes. To help consumers select the right butter for their needs, the U.S. Department of Agriculture classifies the cooking staple into three distinct grades based on various factors such as flavor, color, and texture. If you look closely at butter packaging at the supermarket, you'll likely find a label indicating its official USDA grading.

The USDA divides butter into three grades, with AA being the highest quality, A being the next highest quality, and B representing the lowest grade. Butter with the AA shield is characterized by a superior flavor that is slightly sweet, along with a smooth, creamy texture and uniform, appealing color. Grade A butter maintains a high level of quality, offering a satisfactory flavor and a slightly coarser texture than AA-graded butter.

Grade B butter is the lowest of the USDA grades, which makes it suitable for use where flavor and texture are less important, such as in baking and in industrial applications. Grade B butter's flavor often lacks the freshness and sweetness of its higher graded counterparts, and its texture may be less smooth. While supermarkets typically stock Grade AA and A butter, Grade B butter is predominantly utilized in industrial environments.

The term butter can be misleading

When it comes to grocery store products, the term "butter" might not always mean what you think it does. This is mainly due to the emergence of various butter-like products that don't fit the traditional definition of butter. And we aren't just talking about products that would be hard to mistake for the yellow-hued spread, such as peanut butter or almond butter.

Consumers can find a range of products labeled "butter" at grocery stores that actually contain no dairy. These plant-based "butters" mimic the taste, texture, and cooking properties of traditional dairy butter without being as nutritionally dense. This can present a problem, as highlighted by a 2018 survey conducted by IPSOS. According to the study, more than seven out of 10 consumers believe that plant-based milk substitutes such as almond or soy milk contain at least as much protein as regular milk. Since traditional butter is made from milk, it's logical to infer that similar misconceptions extend to plant-based butters.

Concerned about the potential consumer confusion, U.S. Senators Tammy Baldwin and Jim Risch called in 2023 for the FDA to amend its labeling regulations. "The inaction by FDA harms public health as a result of consumer misperception over dairy products' inherent nutritional value. As a result, it is imperative that FDA enforce its existing standards of identity for dairy in both current and future guidance," they wrote in a letter to FDA Commissioner Dr. Robert Califf (via a press release from Baldwin's office).

Moderate butter consumption can be healthy

Until recently, butter was deemed unhealthy due to its substantial saturated fat content, which has been associated with heart disease and high cholesterol. This perception resulted in a considerable decrease in butter consumption during the 20th century, as highlighted by Elaine Khosrova in her book "Butter: A Rich History." She explains: "People were eating 17 pounds of butter a year in the 1920s, and it dropped to about four and a half pounds by the end of the century" (via MPR News).

While the Heart Foundation advises exercising caution when it comes to butter intake, research published in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology in 2022 hasn't found a significant link between saturated fat and heart problems. This suggests that while you may not be doing yourself any favors by consuming copious amounts of butter, in most cases eating the spread in moderation shouldn't be a cause for concern.

In fact, eating small amounts of butter could be beneficial to health. Some varieties of butter have a high beta-carotene content. Once converted by the body into vitamin A, beta-carotene is associated with improved eye health and a reduced risk of certain cancers, including lung and prostate cancers. Butter is also a valuable source of vitamin D and calcium, which are beneficial for bone health. Moreover, butter contains vitamin E, which promotes skin health.

Butter is easy to make at home

Making butter in the comfort of your own kitchen is easier than many of us believe, requiring few tools and ingredients. Nevertheless, it's best to start the process with heavy cream rather than milk, since turning milk into heavy cream isn't a straightforward process. For those not in the know, heavy cream is the fat-laden layer that's skimmed off the top of milk before it undergoes homogenization.

Heavy cream is the only ingredient required to make butter. Simply pour the cream into a food processor and blend it until the butter fats and buttermilk separate, which should take about 10 minutes. It's also possible to achieve the same results by vigorously shaking the cream inside a sealed jar, although it may take around half an hour for the cream to turn into butter. It's recommended that you run the butter under cold water to remove as much buttermilk as possible, thus prolonging the butter's freshness. Finally, season the butter with salt to taste.

Butter sculpting is a thing

While many of us are familiar with the intricate beauty of sand sculptures, the idea of sculpting with butter may seem like a somewhat novel means of artistic expression. In fact, the unconventional art has deep roots in history, with Tibetan monks having engaged in the creative pursuit for centuries. Crafted from yak butter, the Tibetan figures — known as tormas — have been traditionally created for festivals and religious celebrations. Nowadays, the elaborate sculptures of deities, plants, and animals, which can take months to make in special cold rooms, are displayed to the public at the annual Butter Lantern Festival.

Among the earliest butter sculptures in the U.S. that stood out was likely made by Caroline Brooks, who used the kitchen condiment to make a bas-relief of a woman. Called Dreaming Iolanthe, the piece was showcased at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876. Keeping the tradition alive, today's butter sculptors exhibit their pieces at various fairs throughout the U.S. One such event is the Ohio State Fair where sculptures of a cow and calf, as well as a mystery sculpture, are featured each year. Every year, artists dedicate over 500 hours and utilize upwards of 2,200 pounds of butter to craft these sculptures, which are viewed by roughly half a million people.

Margarine was invented as a butter substitute

Initially called oleomargarine, margarine was invented by French chemist Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès in 1869. Mège-Mouriès invented the product in response to Napoleon III's request for a cost-effective alternative to butter for his army and the lower classes. Unlike today's margarines, which are primarily made from vegetable oils, the original artificial butter was made from beef fat, milk, and salt. Notably, in 1871, Mège-Mouriès sold his pioneering invention to a Dutch company called Jurgens. This venture would go on to merge with Unilever, which is responsible for making the Flora brand of margarine today.

Margarine made its debut in the U.S. in the late 19th century and quickly became a competitor to butter, which at the time was of rather low quality. The dairy industry responded with a campaign aimed at ousting margarine manufacturers through legislation and taxation. For instance, since margarine was normally white, manufacturers started dying it yellow to resemble butter. Butter producers convinced certain state legislatures to ban the yellow coloring of margarine, with some states even trying to force margarine be dyed colors like pink, red, or black.

Despite the valiant attempts, margarine manufacturers ended up winning the battle due to the butter shortages caused by the Great Depression and World War II. According to a Journal of Marketing article via JSTOR, the U.S. saw a one-third reduction in butter consumption and a fourfold increase in margarine sales between the late 1920s and the 1950s.

Butter is a base ingredient in ghee

Commonly used in Indian cuisine, ghee is created by removing milk solids from butterfat. It's surprisingly simple to make it yourself at home. Start by slowly heating butter on medium-low until you see whey rise to the top, then carefully remove it. If you don't want to throw it away, the frothy substance can be used to enhance the flavor of some foods like mashed potatoes. Once the water evaporates and the milk solids sink to the bottom of the pan, gently brown them to give the ghee its distinct nutty flavor. Remove the mixture from the stove, and let it cool down. Then strain it using a cheesecloth or a towel to filter out any remaining browned milk solids. With all the dairy content gone, the ghee can be stored at room temperature in your pantry for up to three months, or it can last up to a year if kept refrigerated.

While many people use the terms ghee and clarified butter interchangeably, they are slightly different. The main factor that sets the duo apart is their preparation process. Clarified butter is produced by melting butter and allowing it to simmer until the milk solids settle at the bottom and the water evaporates, resulting in a translucent butterfat layer. The process of making ghee goes a step further by cooking the butter for a longer period, which browns the milk solids before they are strained out.

Butter has a low smoke point

The smoke point of an oil or fat is the temperature at which it starts to visibly smoke and break down. This decomposition not only alters the taste of the oil, making it bitter, but also generates harmful compounds and free radicals, which can be detrimental to health. Each oil and fat has a unique smoke point, with some more suitable for frying and others better for cooking on low heat. The oils with the highest smoke points include safflower oil (510 degrees Fahrenheit), rice bran oil (490 degrees Fahrenheit), and peanut oil (450 degrees Fahrenheit).

Butter has a relatively low smoke point of around 350 degrees Fahrenheit, which makes it unsuitable for cooking that involves high temperatures such as deep-frying. To overcome this limitation, opt for clarified butter or ghee. Since both spreads have had milk solids removed — the component in butter that burns at low temperatures — they can be subjected to higher heat. More specifically, clarified butter has a smoke point of around 450 degrees Fahrenheit while ghee won't burn until it reaches temperatures of around 485 degrees Fahrenheit.