The 22 Most Surprising Facts About Eggs

Eggs have been cultivated for thousands of years and serve as a versatile dietary staple, a building block of many world cuisines, and an important element in baked goods. They are so vital to the human experience that they've inspired sayings ("a good egg," "to put all one's eggs in one basket"), culinary creations, feats of engineering, and modern farming techniques. Every delicate shell holds together a fascinating and sophisticated scientific marvel, a protein source that's easily raised and mass-produced, and an endless gift from nature (as delivered by chickens).

The egg is so omnipresent that it can easily be taken for granted or perceived as mundane or underappreciated — at least when it isn't Easter season or when a shortage breaks out. Those little white (or brown) oblong things are anything but simple or boring, so let's crack a few trivia eggs to make a knowledge omelet. Whether you take them scrambled, poached, boiled, or over-easy, here are nearly two dozen farm-fresh egg facts.

1. They're not considered unhealthy anymore

For decades, conventional nutritional wisdom held that eating too many eggs was unhealthy for the human heart. A single egg, specifically the yolk, contains around 185 milligrams of cholesterol, more than half of the 300-milligram daily limit once advised by the USDA. A high level of blood cholesterol may lead to a heightened chance of cardiovascular disease and issues, so experts recommended a reduction in dietary cholesterol to help stave off such threats.

However, newer research holds that high blood cholesterol occurs when the liver manufactures cholesterol from excess dietary saturated and trans fats. In the wake of this research, the USDA repealed its cholesterol guideline of keeping daily consumption under 300 milligrams, while reiterating that Americans look out for saturated fat. Since eggs have a negligible amount of that, they don't really contribute to heart problems. They're also loaded with protein and lutein (which assists in eye health), choline (for brain and nerve maintenance), and other necessary vitamins.

2. American eggs must be refrigerated

In the United States, it's commonplace and advisable to refrigerate store-bought eggs. In Europe, chilling eggs just isn't done. This is due to differences in how the eggs are processed. In the U.S., factory farming operations wash and dry freshly laid eggs. This generally provides a nice cleansing, but the procedure removes the cuticle, a natural layer that grows on eggs to protect against germs that lead to salmonella poisoning.

Refrigeration can kill that bacteria, so in the U.S., the law requires shippers and sellers to keep eggs at a temperature of 45 degrees Fahrenheit. In Europe, producers don't wash eggs, leaving the cuticle intact. Consequently, they don't need to be refrigerated and should be consumed no more than 30 days after packing.

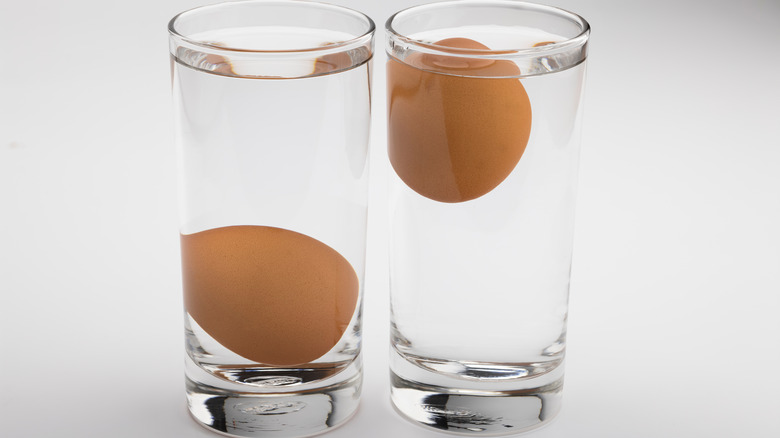

3. A non-buoyant egg is a fresh egg

Maybe the "sell by" date faded off the carton, or the full dozen was transferred to a large bowl and placed in the back of the refrigerator; sometimes an egg's expiration date is hard to discern. There's a simple and scientific way to check it for freshness. Fill a deep bowl or glass with water almost all the way up and place the egg into the bath.

If it sinks, it's a fresh egg, but if it floats, it's at least several weeks old and up to the diner's discretion whether or not to consume it. Eggshells are covered in small holes that allow air to pass through. The longer an egg is around, the more air gathers inside, creating an air pocket that causes it to float.

4. Every part of the egg has a name

All kinds of animals lay eggs, particularly domesticated fowl like chickens. Scientists need words to describe the different parts, so the sections of an egg have a technical name. The eggshell is a type of chorion, or a network of cells that protects its contents. Inside the shell is mostly albumen, the slimy stuff more commonly called the egg white. That's not the same material as the strands that hang down when cracking an egg — that's the chalazae, which keep the yolk in place. The richly flavored and yellow round in the middle of it all is the vitellus. Most folks call it the yolk, which comes from an Old English word that means "yellow."

5. A sell by date is not the same as an expiration date

Most cartons of eggs purchased in a grocery store in the United States come with a date prominently stamped on the side. It's often accompanied by the words "sell by." This becomes a deadline for the eggs inside, a warning to use the contents before they expire and turn inedible or dangerous. In fact, that date is just a designation for egg sellers looking to track inventory and the freshness of products, not an expiration date for the egg buyer. If stored properly in a refrigerator, eggs can be safely eaten for three to five weeks after the printed "sell by" date.

6. There's a difference between free-range and cage-free eggs

"Free-range" and "cage-free" designations both imply that the eggs inside a carton were produced by chickens free to move about a farm. While the birds are granted a limited amount of autonomy, exactly how much and where they can go will vary. Free-range hens spend most of their time inside massive, densely packed chicken houses with access to fenced-in outdoor areas should they want to wander. Cage-free hen-laying eggs are kept in much the same manner, and while they can roam around their indoor facility, they aren't ever allowed to leave those environs. As far as the nutritional benefits of free-range or cage-free eggs go, there are none — biologically, eggs from both kinds of chickens are identical.

7. Most carton signifiers are meaningless

Egg distributors employ many tactics to differentiate their products from the competition's nearly identical wares. These companies are fond of using marketing language that suggests health benefits while skirting strict laws about making such claims. For example, "hormone-free" means the eggs are laid by hens that haven't been given hormones, but that's not really something worth boasting about because it's illegal to give hormone-laden feed to egg-laying chickens in the U.S. "Antibiotic-free" is a similar claim, because antibiotic use in egg farming is extremely rare.

"Farm fresh" means very little, because all mass-market eggs come from a facility that could also be called a farm. "Organic" does carry weight though — eggs with that word on the carton mean they've been subjected to and passed organic certification rules set up by the USDA.

8. How eggs are graded

The USDA offers a grading service for egg producers to assure consumers that eggs abide by a certain level of quality. The rating system consists of three degrees: Grade AA, Grade A, and Grade B. Exactly where on the scale a batch of eggs rates is determined by the perceived quality of the edible parts and the appearance of the shell.

Grade AA, the highest mark, is reserved for eggs with dense whites, round and flawless yolks, and clean shells. The rating falls to Grade A, the most commonly bestowed score for commercially available eggs, if the whites aren't as firm. Grade B eggs have noticeably thin whites, ill-formed yolks, and marred shells.

9. How eggs are sized

Every egg is different, so there will be variations among the 12 included in a carton. They'll differ slightly in size, shape, and weight, which explains in part why the USDA requires that eggs marketed by size be based on the total weight of a full dozen. Federal and state checkers ensure that eggs in the U.S. are accurately sold within five weight classes: small, medium, large, x-large, and jumbo.

A dozen small eggs weigh 18 ounces, medium eggs come in at 21 ounces, large-certified eggs weigh 24 ounces, x-large eggs measure up at 27 ounces, and 12 jumbo eggs weigh 30 ounces. The nutrition inside changes with size, too — a small egg contains 50 calories, and each step up in weight designation adds 10 calories.

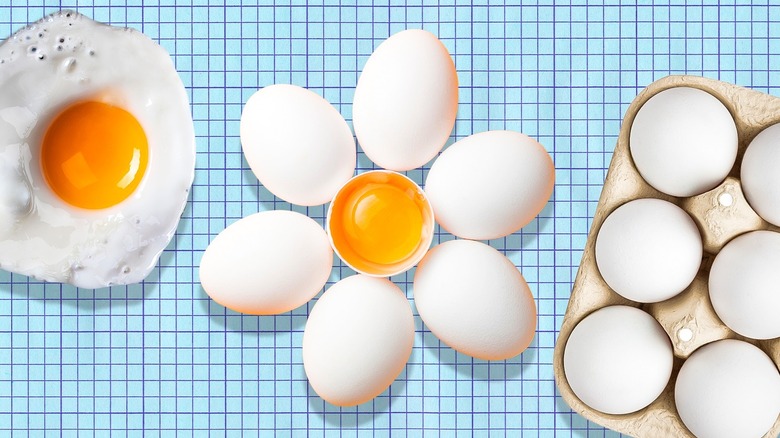

10. The color of an egg yolk is diet-determined

Egg yolks are generally some shade of yellow, although the intensity varies based on what the hen that laid it eats. A yolk on the lighter yellow side suggests its chicken eats a diet primarily made up of feed that's heavy on wheat. If that yolk winds up deep yellow or orange, the hen's feed is abundant with carotenoids, a naturally growing plant pigment. Darker-colored yolks are more commonly found in free-range eggs, laid by chickens that feed on carotenoid-boosting elements, like marigolds or a marigold extract. Dark yolks may seem more appetizing, but there's no nutritional benefit to eating eggs with more vividly colored yolks.

11. An eggshell is mostly calcium

An egg is a natural source of protein, fat, various vitamins, and minerals, including calcium. The shell that carries all that wholesome material is made up almost entirely of minerals — 95% of the 2 grams or so of a shell, by weight, consists of calcium carbonate crystals. Dotting the surface of eggshells, which you shouldn't throw out, are around 7,000 microscopic pores that allow easy airflow. Underneath the shell are two more protective layers, the inner and outer shell membranes. They guard against bacteria entering the egg and prevent the liquid inside from dissipating.

12. A lot of people eat a lot of eggs

Eggs are a crucial element of cuisines around the world, and the supply keeps up with the demand. Globally, the biggest consumer of eggs is China, where the average person eats, in some fashion, 400 per year, a rate of more than one a day. The United States isn't far behind, and is the second-biggest collective egg eater on the planet — Americans consume 320 eggs per person per year. More likely than not, their eggs come from Iowa, the most prolific domestic supplier. Each year, the state's farms produce about 16.5 billion eggs.

13. One hen lays many eggs

Healthy hens, including those raised by large-scale egg farming operations and in backyard chicken coops, lay eggs at a rate of about one per day. The entire biological process takes approximately 24 to 26 hours to complete, so over the course of a year, the average hen winds up producing about 250 eggs.

That number isn't 365 because of the slightly less-than-daily rate and the fact that most hens stop laying eggs for several weeks each year. Typically, chickens enter their molting period in the early days of fall and stop producing eggs. They need to conserve energy to rid themselves of old feathers and grow new ones.

14. The egg came before the chicken

The hypothetical question, "Which came first: the chicken or the egg?" poses both a scientific and philosophical conundrum. It's tricky to conclusively answer without the argument descending into circular logic — the chicken theoretically came first to lay the egg, but then the egg had to have been laid by a chicken, and so on.

Nevertheless, there's a solid and reasonable argument to be made that the egg came before the chicken. Eggs, as a biological entity, predate chickens by millions of years. Numerous other animals begin life inside eggs, including the dinosaurs of long ago. Those prehistoric beasts were born after gestating in eggs and evolved into modern birds, like chickens — which lay eggs.

15. How eggshells get their color

Most commonly sold in brown and white varieties, hens can lay eggs in several colors, including shades of blue and green. The hue of eggs can be predicted; the color of the hen's earlobe generally correlates to the color of the eggs they're most likely to lay. For example, white-eared hens produce white eggs, while red-lobed hens provide brown eggs.

Other factors influence egg shade, too. Just before the egg is laid, the cuticle is applied to protect against the entry of germs. The cuticle, also called a bloom, can affect the color, and so can time — the earlier a hen may be in a laying cycle, the darker the tint on the egg.

16. Green hard-boiled eggs are fine to eat

Eggshell colors vary greatly, but the inside of an egg, particularly a cooked one, is consistently white and yellow. Sometimes a hard-boiled egg will take on a sickly green hue, a color so unappetizing that it seems to serve as a warning to stay away and avoid eating those eggs. It's actually perfectly safe to eat green hard-boiled eggs. It's not bacteria or germs that cause that color to develop but a symptom of over-cooking. Naturally occurring sulfur in the white mixes with iron found in the yolk to form a small and harmless amount of a compound called ferrous sulfide, which has a green color.

[Featured image by Ll1324 via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and Scaled | CC BY-CC0 1.0]

17. Older eggs are easier to peel

When an egg emerges from a hen, its shell is the thinnest and most brittle it will ever be. Since the delicate shell helps form a tight seal around the materials inside, there's little room between layers. As the eggs sit around, the shell grows thicker and tougher, separating more readily from the albumen, or egg white. An older egg, with a more developed shell, is better suited to hard-boiling than a fresher egg because it will be much easier to peel. Eggs that are seven to 10 days old will allow for the chipping away of their shell in larger, cleaner chunks, with a decreased likelihood of accidentally piercing the cooked white.

18. Upside-down eggs last longer

Chicken eggs naturally develop with a narrow top that widens near the bottom. They're logically stored in that configuration, in egg cartons and plastic refrigerator egg holders, but flipping them over can extend their period of viability and edibility. Because eggshells are porous, air slowly seeps in and enlarges the air pocket inside. Storing them the traditional way, with the wide side down, allows that air pocket to grow and make more contact with the yolk, which speeds up spoilage. Turned over with the pointy-end down, that air pocket makes little to no contact with the yolk, thus extending shelf life.

19. Deviled eggs come from Ancient Rome

A popular appetizer, snack, or party food today, deviled eggs originated during the Ancient Roman Empire and were consumed in a similar fashion. Kicking off a large feast for the wealthy and elite, the dish consisted of boiled eggs paired with hot and spicy sauces. That idea evolved into stuffed eggs, a delicacy prepared across Europe, and in the 1800s, the modern deviled eggs recipe of boiled eggs mixed with mayonnaise and other ingredients developed.

At the time, the word "deviled" was used to warn of spicy or hot food (as if the devil served it), and "deviled eggs" were still served in the Roman tradition, with a little heat. The name stuck as the spicy additions gave way to a customary sprinkling of paprika.

20. Humans have been painting eggs for thousands of years

The custom of decorating eggs with dye and paint is strongly associated with Easter in the present day, an evolution of a practice that began with the Trypillians, a culture prominent in Central Europe from about 4500 B.C. to 3000 B.C. The artistic form of written communication stuck around as the areas and cultures associated with what today is Ukraine developed.

As Christianity spread into the region hundreds of years ago, egg decorating with wax and dyes became a Christian custom. It borrowed from a Middle Eastern Orthodox Christianity tradition of using the color red to symbolize the blood shed by Jesus before the resurrection, celebrated by Christians on Easter.

21. The egg carton changed everything and then never changed

For centuries, the preferred method for transporting eggs was inside a basket or wooden crate lined with cushioned material, such as straw. Breakage was such a common problem that by the early 20th century, inventors were inspired to create and market a more effective egg container. In 1903, English box maker Thomas Peter Bethell patented a cardboard tube, the Raylite Egg Box, to package eggs prior to transportation.

That invention proved more effective than baskets and crates, but it was eclipsed in 1918 when Canadian publisher Joseph Coyle patented and introduced the Coyle Safety Egg Carton. Made of thick cardboard with a snug-fitting compartment for each egg, this carton is very similar to the one widely used today, with only small improvements and adjustments instituted over the last 100 years.

22. The record for most-eggs-eaten is in dispute

In October 2013, professional competitive eater Joey Chestnut set a new benchmark in the category of hard-boiled eggs. At the World Hard Boiled Egg-Eating Festival in Radcliff, Kentucky, he downed 141 of them in eight minutes, adding eggs to the list of all the records that Chestnut holds.

However, in 2023, Josh Cottreau, singer for the Australian punk band Fangz, ate 143 in under four minutes while filming a music video. Because Cottreau's feat rests on a claim that's tough to prove, while Chestnut's happened in public at a sanctioned and observed competitive eating event, the latter's 2013 record of 141 hard-boiled eggs remains the official world record.