What It Was Like To Eat At One Of The First Burger Joints In America

Anyone curious about what life was like at the world's first burger joint — or one of the world's first burger joints, depending who you ask — doesn't need to time travel. They just need to travel to New Haven, Connecticut, home to Louis' Lunch. At the turn of the 20th century, Danish immigrant and accidental burger inventor Louis Lassen served up what some argue was the first hamburger. Over a century and four generations later, the proprietors still serve the same burger, cooked exactly the same way, in the same exact spot, owned by Louis' great-grandson Jeff.

To some, this astounding faithfulness can be a little bit jarring. There are just a few items on the menu, cooked in a very particular way. But don't say you weren't warned: a sign right above the chalkboard menu reads, "This is not Burger King. You don't get it your way. You take it my way, or you don't get the damn thing." This may be somewhat off putting to the first-time visitor, but Louis' charm is that it is emphatically not Burger King, or anything like it. It's a trip through history.

Was Louis' Lunch the first burger joint?

Before traveling into the tiny building with a plaque declaring itself the birthplace of the hamburger, we need to address the big cow in the room: is that accurate? It depends who you ask. Some people say the hamburger goes all the way back to the Romans, who published a cookbook in the first century A.D. featuring a minced meat patty.Others claim it was the Mongols, someone in Hamburg, Germany, or a vendor at the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair. Louis' Lunch's most direct competitors include the town of Seymour, Wisconsin, which calls itself the "Home of the Hamburger" and hosts Burger Fest each year, and Menches Brothers in Massillon, Ohio. A 2021 Washington Post article found several newspaper ads from all over the country from the 1880s and 90s, before Louis Lassen set up his lunch wagon, advertising "hamburger steak" and "hamburger sandwiches."

Jeff Lassen remains unconvinced, and told Mashed he thinks it's possible some of the ads could be doctored. The restaurant has defended its claim for decades. It participated in a mock trial competition at the 2006 Hamburger Festival, where it submitted an affidavit from the New Haven Preservation Trust, and the Library of Congress's official recognition of Louis' Lunch as the birthplace of the hamburger. Ultimately, the absence of written evidence makes a definitive answer impossible.

The first burger was improvised in a hurry

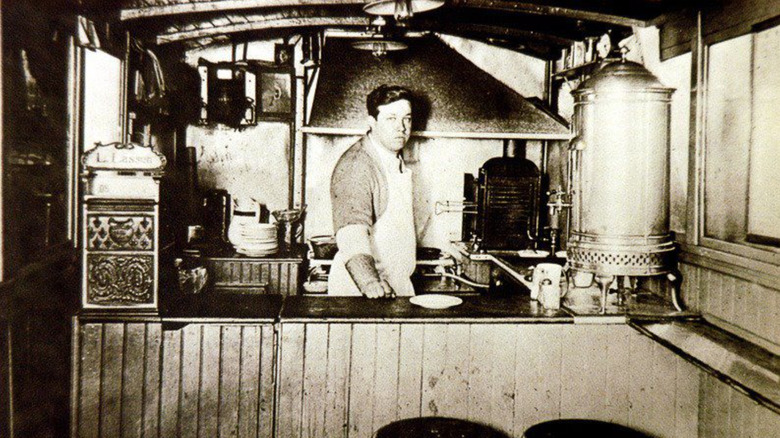

Whatever you believe about the burger origin story, there's no question that the almost accidental birth of Louis Lassen's first burger is a standout moment in the history of the hamburger. Restaurant namesake Louis Lassen was born in 1865 in Denmark, and immigrated to the United States in 1881. He learned to be a blacksmith and did some freelance preaching, but his ultimate legacy began when he began selling butter and eggs from a wooden cart in the back of his New Haven home. The horse-drawn cart started in the back of his home, but in 1895, he moved it to Meadow Street, where he served steak sandwiches to nearby factory workers.

In 1900, the cornerstone of modern fast food began because someone needed lunch in a hurry. According to Lassen family lore, a customer ran up to the cart and yelled, "Louie! I'm in a rush, slap a meatpuck between two planks and step on it!" Louis gathered ground steak trimmings lying around, placed them between two slices of bread, and history was made. In 1917, he moved his business into the tiny brick office of a nearby tannery, where a very similar meal continues to be served to this day.

It's still located in the 1917 building

For a small building, Louis' Lunch is hard to miss. Alone in the middle of a crowded street of row houses is a short, stout brick building with latticed windows with bright red shudders, a medieval-style black door, and a New Haven landmark plaque. In the 19th century, this building was the 9-by-12-foot office of a long-gone tannery. Louis Lassen bought the building in 1917, when it was hardly bigger than his original wagon. The entire operation consisted of four stools at the counter, four individual booths, the famous charcoal broilers, and a gas fireplace. The only items on the menu were burgers and steak sandwiches.

It continued this way until the 1970s, when the city of New Haven wanted to tear it down to clear the path for a medical center. Ken Lassen, Louis' grandson, fought the city for about a decade, and rallied community support. It was almost all in vain until the eleventh hour, when a woman in Florida called up her lawyer and arranged a sale of her property instead. The building was then loaded onto a flatbed truck and relocated to Crown Street, just a few blocks away. The community donated thousands of bricks to expand the building, which is now 18 by 36 feet, and seats 29 people. "A lot of people came up to my dad and said, 'Please, don't make it too big. It won't be the same,'" Jeff remembered.

Burgers were and still are cooked in broilers

In 1917, Louis' hungry patrons would have squeezed onto stools in front of a narrow counter, and watched Louis place two raw patties in between a two-sided gridiron, then put the gridiron inside an ornate 1898 cast-iron vertical broiler. After the meat was cooked, he would place it in between two slices of toasted bread with an onion and a tomato.

Today, not much has changed, including squeezing onto cramped wooden stools with decades worth of graffiti etchings. Each morning, seven days a week, the restaurant staff prepares the mixture with a blend of five different meats (the exact recipe is a closely-guarded secret.) The blend of meats are separated into patties that are a third of a pound, and garnished with thinly-sliced, raw onions. The cooks then place them into the ancient vertical broilers, which have elegant domed tops and two narrow doors embellished with decorative iron swirls. The gridiron is placed between the two doors, and inside, the two patties are cooked by flames on both sides until they are medium-rare. The juices collect into a drip pan below. The burgers are then garnished with tomato, cheese spread, and nothing else. "It's that old famous saying: if it ain't broke, don't try to fix it," Jeff Lassen said. The biggest difference is price. In 1900, burgers cost seven cents, which would still be mightily cheap in 2024, at roughly $2.57. Now, the same burger costs eight dollars.

Burgers have always been placed on sliced toast, not buns

As the burgers roast inside the broiler, slices of bread rotate around another historical artifact still in active use: the 1929 Savory Appliance Radiant Gas Toaster, a conveyor belt of roasting racks that gets the bread nice and golden crispy. The patties are then placed, Louis Lassen-style, between two slices of toast, and cut diagonally. Pepperidge Farm, perhaps best known as the manufacturer of Goldfish crackers, is based in nearby Fairfield, Connecticut, and has been Louis' bread of choice since at least the 1940s.

The fact that Louis' burgers are placed on bread rather than buns is another bone of contention in the hamburger's origin wars. Some argue that a hamburger by definition goes on a bun, and anything on sliced bread is actually a sandwich. We won't weigh in on that, but it's worth noting that even the origins of the traditional rounded hamburger bun are disputed. One story says the bun was created in 1916 by Wichita fry cook and eventual White Castle founder Walter Anderson, who created a bun specifically designed to hold hamburgers because he was tired of meat slices falling out of the bread. Others credit Oscar Weber Bilby, who during Tulsa's 1891 4th of July celebrations took one of his wife's sweet rolls and used it as a vehicle for serving his hamburger meat.

Ketchup and condiments are forbidden

Back in the days of Ken Lassen, anyone who ordered ketchup, or any condiment besides tomatoes, onions, and cheese, would get sent to the back of the line. "Come back when you learn how to order," he'd scold. Today, customers won't get banished, but they'll still be referred to a giant "No Ketchup" sign saying, "Don't even ask."

Isn't that like banishing someone who asks for cream cheese to go with their bagel, or a little extra Parmesan cheese to sprinkle on their pizza? What on earth, many have asked, is so wrong with ketchup? Ketchup, way back when, was invented because the taste of meat was so poor that way back when they needed something to cover the flavor up, Jeff Lassen told us. "We grind our meat fresh every day, we always have since day one, [and] it's the best meat available to us and/or you, and [we] want you to taste it, and enjoy it, as opposed to covering it up."

The aversion to ketchup has joined the tiny brick building and antique broilers as one of Louis' many famous quirks. In addition to its large sign, some workers wear anti-ketchup T-shirts, which are also for sale.

There were no fries

Louis' takes numerous precautions to avoid the evils of ketchup, and one of those is avoiding french fries. According to Jeff Lassen, fries are like a ketchup gateway drug. "French fries require ketchup," he told Mashed. "If you put it on fries, [it's] going to lead to being on burgers."

But that doesn't mean the restaurant completely stays away from any potato products. It first started selling potato chips, almost by accident. According to Lassen, his father once came across a box of potato chips in the middle of the road on the way to work. The box contained several unopened bags of chips, and he decided to sell them. To this day, they still sell Deep River potato chips, made in Old Lyme, Connecticut. Not long after they started selling potato chips, an employee suggested making potato salads, and today, they offer salads with giant potato chunks, eggs, and onions.

Cheese didn't come around until the 1950s

There is one element of a typical burger experience that has made its way into Louis' Lunch, though it took about 50 years. Sometime in the 1950s, Ken Lassen began adding a sharp cheese spread to the burgers, similar to Cheez Whiz or Velveeta, because the broilers couldn't accommodate a regular slice of cheese. It was a popular addition, and Jeff Lassen said that these days, about nine in 10 customers order cheese with their burgers. Customers in the know who want the full cheese, tomato, and onion with their burger ask for "the cheeseworks." But even though that name suggests extra cost, the "cheeseworks" is the same price as a plain burger.

Naturally, the cheeseburger also has conflicting origin stories. One story credits Lionel Clark Sternberger, who was working at The Rite Spot in Pasadena in 1924. According to one story, Lionel burnt a patty on the grill, and quickly slapped a slice of cheese on the burger to hide his mistake. One thing's for sure, a cheeseburger at Louis' Lunch is it's own creation entirely.

Slowly, other menu items crept up

After cheese was introduced, new items began creeping onto the menu. The Lassens noticed that business was especially slow on Fridays, a day when traditional Catholics don't eat meat. To compensate, Jeff's mother, Leona "Lee" Lassen, began making tuna sandwiches, since fish is permitted. That quickly became popular, and to this day, Fridays are tuna sandwiches day. In the 1960s, Lee also began cooking pies, another hit that's turned into the restaurant's famous dessert. Her recipes, which employees still follow to this day, included apple, blueberry, strawberry rhubarb, peach, Key Lime, and even smores, all for $5 a slice. Check the chalkboard inside Louis' for the pie of the day.

When Louis Lassen was at the counter, Jeff believes that the only drinks available were likely coffee, Pepsi, and water. Today, Pepsi, water, Snapple, and coffee are all available. But the classic Louis' pairing is Foxon Park root beer, for just $2.75. This East Haven company started in 1922 brews root beer, birch soda, tonic water, ginger ale and much more, which all use cane sugar rather than artificial sweeteners. It's become known as the perfect accompaniment to both Louis burgers and the thin-crust, coal-fired New Haven-style pizza.

The restaurant doesn't deliver

A restaurant that doesn't allow ketchup isn't likely to feature many of the other amenities common to burger joints. According to Jeff Lassen, the old 9x12 building didn't even have a restroom — there was simply no room. The restaurant was also cash-only until the COVID-19 pandemic, but now accepts debit and credit cards.

The pandemic was a tough stretch for the restaurant too small to allow for any proper social distancing. For the first time, they opened up a window with a side entrance to deliver orders. That window has since closed, and it goes without saying that anything resembling a drive-thru is not even close to what Louis' is about. On crowded days, when there's a maximum of 29 people inside, long outside lines can start to form.

Customers can call in orders ahead of time, but you can't order online or on an app. Jeff Lassen said they briefly experimented with delivery in the early '90s, around the time they opened at night, but it was too difficult to find consistent drivers and also tend to all the customers in line. Lassen said he has no desire to sign on with any food delivery apps, which often hold restaurants liable for order issues, and charge restaurants fees of around 20% per order. So for the foreseeable future, if you want to eat Louis' lunch, you need to cram inside Louis' house.

It's been in the Lassen family for four generations

Ever since Louis first set up his wagon nearly 130 years ago, he and his descendants have been working hard to keep his dream alive. For many years, Louis manned the counter alone, but starting in the Great Depression, three family members worked eight-hour shifts to keep the store open all night.

Jeff said he rarely saw his father growing up. For periods of time, Jeff and his grandmother, mother, sister, and brother also worked shifts. There were times when Jeff wasn't sure he wanted to take over, but the business was struggling to find help. He graduated high school on a Friday, and got behind the counter Monday morning. Even though he thought it might be just a year or two, he's been there ever since, and now manages about seven part-time employees. "It's a lot of work," he said. "[It's] a lot on the family."

Over the years, some people have offered to relieve the Lassens of this burdensome birthright: at one point a fast food chain offered Ken $5 million for the business (about $29 million in today's money), but he refused. In the 2000s, Jeff got another offer for "a large sum of money," he recounted. "]But it's] just not us. [It's] not in our DNA. [We] like to stay where we're at, do what we do, and keep things the same."

Louis' is kind of a big deal

If Ken or Jeff had accepted those lucrative offers, Louis' might be just another nondescript drive-thru, and we likely wouldn't be writing this article. But because they've stayed so fastidiously faithful to their original menu and decor, and continued to insist they're home to the world's first burger, they've become pretty darn famous. Louis' is listed in the Library of Congress as the home of the world's first hamburger. It ranked first on the Travel Channel's 101 Tastiest Places to Chow Down, and placed highly on Esquire's "Best Late-Night Food in the U.S.A," Oprah's 20 Best Burgers in America, Food and Wine's best burgers in Connecticut, Frommer's 500 Places for Food and Wine Lovers. It is also featured in books about hamburgers historyand the best roadside food in the United States.

What's more, it's located just a five-minute walk from Yale University, and Yale alumni like George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush have eaten there, according to the book "BBQ USA." Jeff Lassen said that over the years, many celebrity Yale parents have eaten there with their kids, though he wouldn't say who. The one thing he did disclose was that when Steven Spielberg was shooting "Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull" on the Yale campus, some actors stopped in.