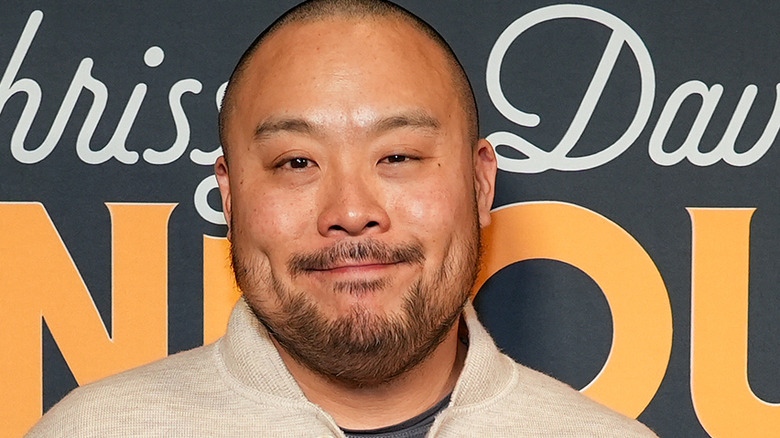

Tragic Details About David Chang's Life

David Chang will be the first to admit he suffers from existential dread. In fact, he's fueled by it. Being hard on oneself is a job requirement if you want to make it into the upper echelons of the culinary world, but Chang, a professional self-punisher, claims it's a big part of why he became a celebrity chef in the first place. He'll also tell you that "celebrity chef" is a title he has found difficult to embrace — but as the founder of Momofuku restaurant company, who hosts a podcast and stars in multiple food and travel series, the designation is pretty unavoidable.

"I was an egomaniac with low self-confidence," he writes in his 2020 memoir "Eat a Peach," a story that is as much about Chang's rise to prominence in the late 2000s New York City dining scene as it is about his tortured psyche. Between his revelations in "Eat a Peach," where many of this feature's quotes have been sourced, plus a steady stream of media coverage over the years, Chang's persona has become a complicated one. The highs and lows that forged his path to success are the same sticking points that have tested his professional reputation. How could Chang, a chef with so much going for him be so intensely angry? Here we'll go behind the comeuppance and controversies of Chang's story to reveal the tragic details that have shaped this prolific chef's life.

Imposter syndrome affected him from an early age

A theme throughout David Chang's "Eat a Peach" is the near-constant voice inside his head that says, "I'm not supposed to be here." These are the last words of the prologue and the sentiment echoes again and again. Why? Because Chang has grappled with imposter syndrome for most of his life.

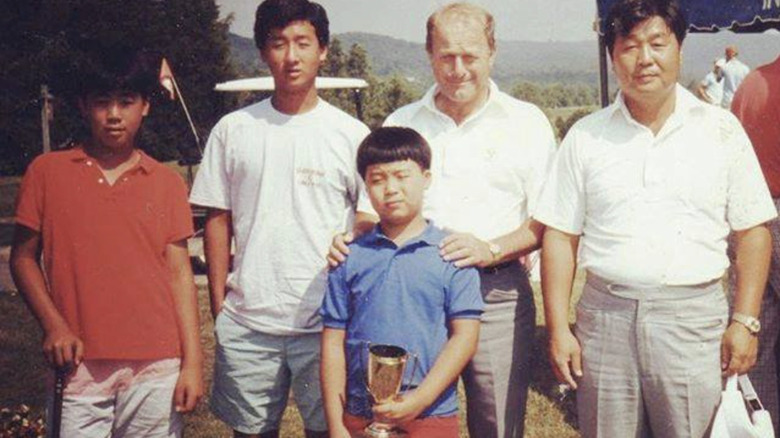

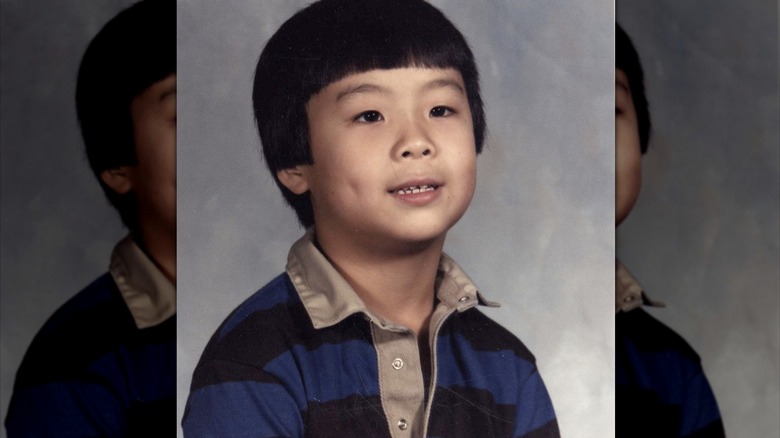

Growing up in Northern Virginia, Chang had prodigious abilities as a golfer. His father owned a golf supply store and pushed him to excel at a time when few Asian kids were golfing. In his memoir, Chang recounts spending 360 days a year refining his golf game. He won two consecutive state championships by age nine, but in his early teens, his confidence ruptured. "I got into my own head and stayed there. Kids I used to destroy began to catch up and then surpass me ... That embarrassment defined me for a long time."

When Chang began gaining widespread recognition as a chef, it was almost impossible for him to acknowledge. He was nominated for Rising Star Chef of the Year at the 2007 James Beard Awards, (his second nomination in a row) yet could hardly bring himself to attend the ceremony. He writes, "I respected the awards deeply, I just didn't respect myself, which made it all the more difficult to picture myself in a tux, strutting past those pretty fountains in Lincoln Center Plaza." He won that night, and deflected the attention by drinking heavily.

Tiger parenting left him emotionally scarred

Many Asian Americans who are the children of immigrants have opened up about their experiences with "tiger parenting," a childrearing style that has been associated with East Asian cultures. This stringent manner of parenting is used as a means of pressuring children to achieve a high level of academic success, however, a study from the American Psychology Association showed that tiger parenting does not turn children into prodigies. David Chang would agree.

Reflecting on his upbringing in the opening pages of "Eat a Peach," Chang describes how his father's love felt "distinctly conditional" and goes on to say that the term tiger parenting "gives a cute name to what is actually a painful and demoralizing existence." Chang was a mediocre student who studied religion at Trinity University in Hartford, Connecticut, admittedly drawn to it because it was "the farthest school from home that I could get into." He made below-average grades while there and felt incapable of making his parents proud. Though he understands that many first-generation Asian American kids were raised under much tougher circumstances than his, Chang maintains, "when you live with a tiger that you can't please ... you're always afraid." It proved to be a feeling that lingered. He would go on to tell Hemispheres Magazine, "You can blame my dad for me not being able to accept any kind of praise."

Growing up, he had complex feelings about his race

Chang has always liked Asian food, but like many kids growing up in the 1980s, he felt a twinge of embarrassment over the smells of Korean cuisine that overtook his boyhood kitchen where his grandmother and mother cooked often. In a soft act of defiance, Chang would eat "mozzarella sticks, chicken fingers, Hungry-Man dinners" when the women weren't around. "Latchkey kid fare, which was all right by me." Yet as he got older, his feelings around race spread to more than just food.

In "Eat a Peach," Chang recalls his high school days, "I wasn't Asian enough to hang with the other Asians ..." When he entered college, "The white girls at school were explicit in their pronouncements that they would never be seen with an Asian man." These life experiences would inform Chang's pioneering role in the "#uglydelicious movement." Speaking to HuffPost in 2018, Chang said, "The movement speaks to many Asian-Americans like myself, who grew up experiencing a tug between two cultures."

It hasn't been easy for Chang to navigate through the intricacies of cultural influence that contribute to an ongoing conversation about race, identity, and food — especially in America. Still, he understands the importance of paying respect to the places and people behind the food. In many ways, these personal experiences around race and cuisine would become of extraordinary use in the early days of his flagship restaurant, Momofuku Noodle Bar.

Both of his parents passed away from cancer

Chang's mother Sherri was diagnosed with breast cancer when he was still in college. She beat it, remaining cancer-free as Chang entered his early twenties — right around the time he left his corporate office job in pursuit of becoming a professional chef. Chang climbed the ladder from a jittery enrollee at Manhattan's French Culinary Institute to an unpaid job in fine dining. Just as he was starting to gain his footing, Sherri's cancer came back.

What made the second diagnosis especially tough was that Sherri was undergoing treatment while Chang's father and brother were embroiled in a family feud. Sherri would go on to fight cancer on and off for 26 years until passing away in 2022. In an Instagram post, Chang vowed to "carry on her love, strength and kindness."

Although Chang's father Joe didn't battle cancer as long as his wife, cancer of the bile duct claimed his life in June 2020. This, too, hit the chef hard. On X, the platform then known as Twitter, Chang wrote, "Like many immigrant kids ... I had a very complicated relationship with him. But I loved him and oftentimes try to imagine what I would be like if I survived the Korean War and lived in America in the 1960s not speaking the language or knowing anyone. Puts things into perspective."

He felt ashamed for having suicidal thoughts

"Opening Noodle Bar had been a last-gasp attempt at finding my place in the world before giving into darker impulses." This is the way Chang describes the origin of his first restaurant in his memoir. He elaborates, "Momofuku was my identity and it was born of my depression." Dark thoughts had plagued Chang since high school, and they were a source of deep shame.

He tried journaling his feelings, only to be mocked by a classmate who found what he had written. Therapy and antidepressants were also points of embarrassment back then, so he blew them off and embarked on an aimless trip in Japan after college. He began to fixate on suicide.

Determined not to burden his parents with the humiliation of his suicide, Chang vowed to make his death look accidental. He rode his bike recklessly through Manhattan traffic. He fell through a glass table during a New Year's Eve drink and drugs binge and wound up in the ER. Once, he walked in front of a reversing city bus.

Chang revisited therapy and ultimately found a doctor he connected with. His doctor was the first person he told about wanting to open a restaurant inspired by the unpretentious establishments he'd visited in Japan. Recounting the events that led up to Momofuku, Chang says, "I was ready to die, and I had something I needed to get off my chest before I did."

He's battled extreme anxiety

He has long maintained that he performs best when the odds are stacked against him, however, Chang's bloodthirst for pressure allowed his everpresent anxiety to metastasize — sometimes dangerously. "I'd actually come to depend on the emotional and mental instability." he writes in "Eat a Peach." The restaurant business thrives on controlled chaos and immense pressure. Chang knew this and unabashedly leaned into his extreme tendencies to succeed, creating a dark situation in which he could embrace the very anxiety that threatened to flatten him. It affected his health.

As he prepared to open his third restaurant, Ko, Chang became "even more of a neurotic mess. I'd have panic attacks at work and try my best to hide them from the staff. I experienced the nightmare that is shingles and a bunch of other psychosomatic crap." He was prescribed two different medications to combat the physical and mental symptoms of his anxiety separately, but "was still drinking my face off."

Anxiety and an addiction to work were psychologically damaging and professionally fulfilling at once. It was as if he needed to struggle emotionally to survive. "I crave that resistance ... It's not just helpful, it's necessary. You think a salmon really wants to swim upstream and die? They have no choice. That's how I feel too."

His anger has caused issues with co-workers

Chang reveals in "Eat a Peach" that he's "always been angry ... the slightest error or show of carelessness from a cook could turn me into a convulsing, raging mass." This made him a toxic leader. Momofuku Noodle Bar was in its infancy when an early-era food blogger posted on the eGullet forum to share his experience there. "Last night, the presentation was wildly inappropriate ... I was distracted from reading the menu as Mr. Chang reprimanded his dishwasher, ordering him to speak-up ... Mr. Chang, a large, physically intimidating guy, began to scold the cook, leaning over his shoulder, he brought his cook to the verge of tears, told him he was going to be fired, and thus made it impossible for me or my girlfriend to enjoy ourselves."

As his success grew, so did his volatility. At Momofuku Seiōbo, Chang's casino restaurant in Sydney, Australia, he screamed at a maintenance man for whistling and threatened him with a knife. Though the event almost got him deported from Australia, Chang claims he was in a blackout state of anger and doesn't remember the details. Shortly after "Eat a Peach" was released, Hannah Sellinger, a former Chang employee, penned a searing review in Eater, disclosing that Chang had traumatized her and others yet made his anger issues only about himself. When asked to comment, Chang said he does not recall the instance Selinger described.

He was diagnosed with bipolar disorder ... and hid it

"I would do anything to see what everyone else sees," Chang said of his mental health journey in "Eat a Peach." He has worked with the same psychiatrist since the early 2000s but only received a diagnosis in the last few years: bipolar disorder with an affective dysregulation of emotions.

His first experiences with mania were in Japan post-college, "the largest Asian man within thirty miles running around and around and loving it ... I had boundless energy. I felt invincible. I finished 'War and Peace' in a couple of days." The dramatic lows were equally intense and sometimes lasted months. "Through the haze of doubt and confusion, one thought began to surface repeatedly: I wanted to die."

Being bipolar was something Chang suffered in secret, yet its effects were telling. When his mentee died of an overdose days after Chang scolded him over the phone, the tragedy triggered a morose cycle. "In the months that followed I put on fifty pounds ... I'd order pizza at 3 a.m. ... I couldn't fall asleep unless my stomach hurt ..." His fried chicken chain Fuku, was born out of an unmedicated manic state.

Simultaneously, affective dysregulation puts Chang in a temporary psychosis where he "can't tell friend from foe." It's the driving force behind his anger. Chang knows his illness will always be a struggle, "I wish I could convey ... how hard I've tried to fight it."

One of his closest mentors committed suicide

Chang met Anthony Bourdain under the pretense of a public speaking event at the 2009 New York Wine & Food Festival. Chang was a well-known New York chef — but not a public speaker by any means. Bourdain, on the other hand, was a natural. The speaking event turned out to be a cutting chat between two strong personalities (their panel discussion was titled "I Call Bullsh*t!"), and Bourdain became both a friend and mentor to Chang. "He looked out for me, and I became fiercely protective of him, too. The way brothers do," Chang wrote in "Eat a Peach."

Chang was often uncomfortable in the spotlight and had trouble owning the public persona of a bad-boy chef. Bourdain, well-versed in both, helped him navigate the progression from being a famous chef in the kitchen to a celeb chef on TV. Their PBS and Netflix special "Mind of a Chef" won a James Beard Award in 2013.

When Bourdain died by suicide in 2018, it shook the pop culture world. The loss hit Chang hard, too. To cope, Chang decided to pen his memoir — which would mean going public with his bipolar diagnosis. In a candid interview with People, Chang said, "It wasn't supposed to happen to him. That was supposed to happen to me. He was supposed to hold it together for all of us."

A longtime collaborator was canceled for toxic behavior

Chang and food writer Peter Meehan met when Meehan reviewed Momofuku Noodle Bar for the New York Times. They became fast friends and colleagues and collaborated so often that when the first Momofuku cookbook was released in 2009, Meehan served as a co-author. Their friendship spanned over a decade.

Meehan was an editor for Lucky Peach, a quarterly magazine celebrated for its innovative convergence of food and journalism (Lucky Peach shuttered in 2017). He also appeared alongside Chang in Season 1 of "Ugly Delicious." Then suddenly, it all ended.

After Lucky Peach, Meehan edited the food section of the Los Angeles Times — a position he felt inclined to abuse. In 2020, an LA Times staffer used X, the platform formerly known as Twitter, to post a thread as a means of airing some troubling information about Meehan's conduct. This kicked off a deluge of damaging reports. Former Lucky Peach employees and those who worked under him at the LA Times described Meehan as a man prone to outbursts, sexual harassment, and verbal bashing.

Meehan resigned and his social media accounts vanished. Meanwhile, Chang distanced himself from his old friend. In a request for comment from Eater, Chang said he couldn't disclose much about Meehan for legal reasons but, "Had I been better, had I created an environment that was a polar opposite, with no shades of black or gray ... I can imagine a scenario where they would have come to me, and that's what I've been wrestling with."

Despite his accomplishments, he still has a spotty reputation

After the release of "Eat a Peach," Chang faced a lot of pushback for acknowledging his poor behavior without going out of his way to make amends to those he hurt — even abused — along the way. On Reddit, a former Momofuku employee called him an "adult toddler." Another Redditor pointed out, "During the Momofuku days, he was nasty to all of his employees in such a grevious [sic] f**king fashion."

Chapter 15 of his book is a prime example of the hyperfocus Chang puts on himself in tough situations. In a painstaking series of copyediting style marks, Chang crosses out the vitriolic comments he made and replaces them with red-inked explanations of how he felt at that moment. It's understandable why Chang approaches his previous wrongdoings this way, especially considering the mental illness he's up against. Even so, many dismissed this as yet another self-flagellating act from a pompous celebrity chef.

Similarly, when his friend and collaborator Peter Meehan was effectively canceled and retreated into obscurity, several of the accusations were the same criticisms Chang has come under fire for. Unlike Meehan, Chang has never been accused outright of sexual harassment, but the violent tantrums and public humiliation of staff members that characterized Meehan's undoing were right out of the Chang playbook. Chang has committed himself to self-reflection, but a reputation flecked with toxicity remains.

His restaurants are closing

"I could sense a palpable Momofuku fatigue in the air. It had become easy to write off our influence." Chang played a leading role in the massive popularization of ramen restaurants in America. He was also a pioneer in capitalizing on modern ideas surrounding fusion, opening restaurant after restaurant in the span of a decade or so. At his peak, Chang had a hand in more than a dozen restaurants. Like other established restauranteurs, he buckled down during COVID-19, but the post-pandemic years saw Momofuku closures that once seemed unfathomable.

In the 2010s, Momofuku Noodle Bar expanded into a small chain. There was a second Manhattan location, one in Washington, D.C., another in Toronto. Restaurants of other names — some under the Momofuku umbrella, some not — dotted the globe. Many are gone. Chang's midtown Manhattan restaurant Má Pêche permanently closed in 2018. Momofuku Seiōbo, Chang's first international outpost in Syndey, Australia, said goodbye in 2021. The pair of Noodle Bars in Manhattan are still standing.

Perhaps the toughest to see go were his second restaurant Momofuku Ssäm, and Ko, his third — both in Manhattan. It was Momofuku Ssäm, which opened in 2006, that first gave Chang the belief that Asian fast food could be mainstream. Ko opened in 2008, was notoriously hard to get into, and retained two Michelin stars since 2009. It was the only Chang establishment bestowed the honor. Both Momofuku Ssäm and Ko closed in 2023.