What Happened To Burger Queen And Other Facts About The Fast Food Chain

Now a hazy historical afterthought overshadowed by more robust and aggressively expansive competitors like Burger King, Dairy Queen, and McDonald's, Burger Queen was once a burger juggernaut in the parts of the Midwest and Southern United States where it operated. Starting as a single burgers-and-shakes drive-in, Burger Queen would open hundreds of restaurants in the '60s and '70s. Customers loved its take on massive cheeseburgers, big and saucy sandwiches, fish, chicken, and other now commonplace fast-food items. Smaller towns in Kentucky, Tennessee, and Indiana were very receptive to Burger Queen, which flourished until its sudden disappearance in the 1980s.

But Burger Queen didn't really go anywhere, nor did it ever fully end operations. The chain continued to operate under a new name, with new people, and with parts of its menu incorporated into other restaurants with whom it once competed. Here's the story of the rise of Burger Queen to mid-20th century prominence and importance, as well as that of its fall and quiet perseverance.

Burger Queen started in Florida

Burger Queen has endured and adapted in the eastern United States in one form or another for nearly seven decades. In its very first iteration, it was a simple drive-in-style fast-food restaurant, like so many others that popped up around the country in the 1950s. In 1956, Harold and Helen Kite capitalized on the traffic of families heading to and from Cypress Gardens, a small amusement park in Winter Haven, Florida, a suburb of Orlando. They opened Burger Queen, a food stand where customers enjoyed the novelty of ordering and dining from inside their cars. Burgers, shakes, and chicken were especially popular items from Burger Queen's simple menu.

The Kites had a thriving business on their hands right away. After just two years of opening the restaurant and subsequently working it into a bustling operation, they sold Burger Queen. Harold Kite parlayed the substantial profits from the sale into other ventures, buying into real estate deals and a motel while also landing a job selling freezers. The Kites would once more wind up in control of Burger Queen when they agreed to buy it back after the new owner couldn't stand the tremendous labor of food service.

The restaurant expanded after a move to Kentucky

Harold and Helen Kite were content with operating just one Burger Queen in Florida. They never seriously worked at expanding the business until half a decade after its inception. In the 1960s, the Kites sold the franchise rights to Burger Queen to George Clark and Michael Gannon, a pair of entrepreneurs who'd previously been unsuccessful in running other restaurants, including Henry's Hamburgers and Dairy Queen.

Clark and Gannon set about making Burger Queen into a multi-outlet business in 1963, opening nine more restaurants in Florida and dozens in Clark's home state of Kentucky. The business moved into Indiana and Tennessee, generally thriving in areas where bigger concerns like McDonald's hadn't yet set up shop. Burger Queen expanded rapidly and successfully. Just 10 years after signing on as franchisees, Clark and Gannon (who dropped out of the business in 1970) had opened 50 Burger Queen restaurants in three states. By the end of the decade, there would be 171 restaurants under the Burger Queen banner in seven states.

Its fish spinoff flopped

One of the most prominent and industry-wide trends in fast food in the 1960s and 1970s was adding fish to the menu. Burger Queen partook in the craze, with a brief fixation on fried fish. Following the successful introduction of the Filet-O-Fish sandwich at McDonald's and the Whaler at Burger King, Burger Queen offered a fish and chips platter — battered cod, fries, and crispy bits. The fish sold very well in 1978, no doubt helped by a Burger Queen advertising campaign starring actor Abe Vigoda, who at the time was playing a character named Fish on the hit television sitcom "Barney Miller."

Burger Queen was very proud of its fish, so much so that in the mid-1970s it tested the idea of a separate, seafood-centric fast food enterprise. The Burger Queen offshoot, King Neptune's Seafood Galley, came and went without expanding too far, but fish remained a staple of the Burger Queen menu.

Burger Queen had to adopt a different name in England

Business was booming for Burger Queen in the 1970s, so much so that the company was able to expand into new markets. Setting its sights on the United Kingdom, Burger Queen collaborated with local restaurant company Grand Metropolitan to open outlets in England. But in a country operating under a monarchy, with Queen Elizabeth II the crowned ruler from 1952 to 2022, Burger Queen's leaders felt it inappropriate and unseemly to sell fast food under the name that had served it so well in the democratic United States.

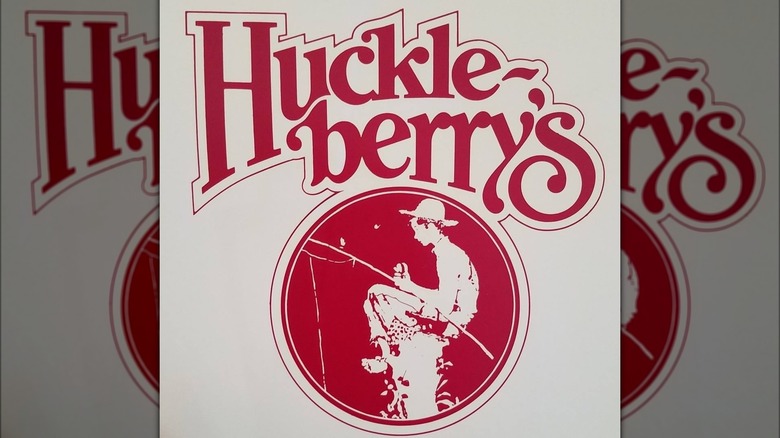

So, in 1979 the British offshoot was christened with a rather down-home, all-American name: Huckleberry's. If the name alluded to "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn," the world-famous 19th-century novel by Mark Twain, the new restaurant's logo made that connection undeniable, featuring a boy sitting on a rock holding a makeshift fishing pole. The image itself was inspired by a work by 20th-century American painter Norman Rockwell.

The first Huckleberry's outlets opened in the Greater London and Hertfordshire regions and sold Double Decker Burgers, Double Cheeseburgers, and boxes of fried chicken. The chain expanded throughout southern England in the 1980s and also introduced milkshakes and fried fish to the menu. The international experiment came to an end in 1986, when Grand Metropolitan sold off Huckleberry's to other corporations, resulting in its conversion into other burger establishments, such as Burger King and Wimpy.

Burger Queen wasn't much like its competition

When George Clark helped take over Burger Queen's operations in the 1960s, he didn't just expand the reach of the restaurant, he completely reformatted it. While drive-through window service eventually replaced drive-in-style restaurants, Clark sought to emphasize the spacious dining rooms of Burger Queen locations. That stemmed from a personal distaste for eating in his car — years earlier, a kid spilled their milkshake in his, reaffirming his opinion that people should eat at a proper table, sitting in a chair. Burger Queen encouraged customers to hang around and dine on familiar American foods served up quickly. For this reason, it more closely resembled a diner or the no-frills mid-20th century restaurant called a coffee shop, than a heavily franchised burger joint.

Burger Queen's growth plans differed from that of other burger places at the time. While McDonald's and other fast food companies made a habit of establishing restaurants near interstate exits to attract hungry travelers, Burger Queen aimed to make its restaurants regional hubs. Clark oversaw an expansion plan that placed Burger Queens in the county seats of rural areas, which would bring in customers from the surrounding towns. Many of those diners were either on their way to or coming back from another big development of the 1960s and 1970s, also placed in and around hub cities — shopping malls.

Dairy Queen sued Burger Queen

Burger Queen isn't the first fast food outlet to grow its business by focusing on underserved small towns, nor is it the first to prominently feature an authoritative, monarchical word in its name. If "Burger Queen" reminded customers of "Dairy Queen," that was no accident, or at least that's what the operators of Dairy Queen alleged in an early 1970s lawsuit. Dairy Queen's parent company filed suit against Burger Queen, alleging trademark infringement for its similar and derivative use of "Queen" in its name, thus leading to customer confusion in the fast food marketplace.

Faced with costly legal proceedings from a much larger accuser, Burger Queen settled with Dairy Queen before the case saw the inside of a courtroom. After the very real prospect of having to change its name, Burger Queen was allowed to keep it, but there was one big stipulation to appease Dairy Queen. The hamburger-focused company agreed to never move into Dairy Queen's specific product territory and sell the chain's signature item: soft-serve ice cream.

Burger Queen imitated McDonald's

Not only did Burger Queen's name allude to other big national chains — Burger King, Burger Chef, and Dairy Queen — but it cribbed directly from McDonald's. McDonald's included the first Big Mac on its menu in 1968, and it was an innovation in fast food — a multi-tiered burger featuring two discs of ground beef and a third half of a bun in the middle. As the chain's earworm of a jingle reminded customers, the Big Mac is built from "two all-beef patties, special sauce, lettuce, cheese, pickles, onions, on a sesame seed bun." When Burger Queen unveiled the Royal Burger, it was almost an exact copy of the Big Mac. It was constructed out of two beef patties, Burger Queen Special Sauce, lettuce, cheese, and, as per the advertising, an "individually toasted triple decker bun." In other words, it was a Big Mac with a different name.

Another hallmark of McDonald's success was the young customer-attracting clown mascot Ronald McDonald. A nationally known character by 1970, Burger Chef's advertising lead Joe Bonura suggested the smaller chain invent a similar kid-friendly character to headline its marketing materials. After rejecting a cowgirl named Queen of the West and a dog named Queen the Dog (they didn't want to create a link in customers' minds between Burger Queen and dog food), Bonura arrived at Queenie Bee.

The company had some memorable mascots

Joe Bonura took a roundabout way to create Queenie Bee. During a brainstorming session with an associate, a dog mascot idea became an amorphous concept called Queenie the D, which evolved into Queenie the B. It wasn't much of a step then from B to bee, and Queenie Bee was born. While Burger Queen boss George Clark found the whole idea a tad embarrassing and undignified, he signed off on it and let Bonura and his advertising team develop the campaign.

Bonura hired a Louisville grade-schooler named Joyce Murphy to portray Queenie Bee in public promotional appearances, on children's TV shows, and in local TV commercials. Wearing a helmet and a bee costume, Murphy often sang a newly written jingle, "It's Burger Queen for Me," a close riff on "An Actor's Life for Me," from Disney's 1940 adaptation of "Pinocchio." Aiding Murphy's performance in the branding was an illustration and animation of Queenie Bee, happy-faced and devoid of an intimidating stinger. In cartoon form, Queenie Bee appeared in TV commercials and all over Burger Queen's signs and marketing materials.

Burger Queen became Druther's

Struggling to connect with customers and grow its business, Burger Queen Enterprises engaged the services of Lippincott & Margulies, a New York-based corporate consultancy that specialized in rebooting and updating older brands. Following extensive research, conducting focus groups, and weighing many courses of action, the consultants, along with an advertising agency and Burger Queen executives, opted to rename the whole business. So, in 1981, Burger Queen officially became Druther's Restaurant, setting it apart from the similarly named competition while also freeing it from having to focus on burgers, inviting in all kinds of menu possibilities with the more generic title. Further, with Druther's, the organization could federally register its name as a trademark, which it had never done with Burger Queen.

Coming along with the radical name change were some departures in marketing. In came a new advertising slogan, "I'd ruther go to Druther's," and in-store signage. It also eliminated the Queenie Bee character and introduced a new mascot. That figure was Andy Dandytale, a drawling, banjo-carrying man who told tall tales and implored children to head into their local Druther's for a "Dandy Dinner" kids meal. But in its day-to-day operations, Druther's didn't function all that differently from Burger Queen. It kept the same owners and management, maintained its headquarters in Kentucky, and retained the same core menu.

What was left of Burger Queen became Dairy Queen

Burger Queen and Dairy Queen were direct competitors for more than two decades, both angling for fast food customers primarily in small towns in the American Southeast and Midwest. In November 1990, Dairy Queen decidedly won the war once and for all when it absorbed most of what remained of its smaller rival. Having changed its name from Burger Queen to Druther's in the early 1980s, the parent company signed a deal to become Dairy Queen's territorial operator in Kentucky and surrounding states, including Tennessee and Indiana.

Druther's comprised 145 outlets at the time, and plans were made to convert around 100 of those restaurants into Dairy Queens by March 1991. That all worked out well for Dairy Queen, whose corporate parent company bought outright 31 Druther's-turned-Dairy Queens. While the plan led to the slow demise and ultimate disappearance of Druther's, the acquisition boosted Dairy Queen. By 2000, the Dairy Queens that used to be Druther's restaurants (and before that Burger Queens) represented the top-selling outlets in Dairy Queen's international network of more than 6,000 locations.

Dairy Queen's breakfast is Burger Queen's breakfast

Fast food restaurants moved from lunch and dinner fare into breakfast in a meaningful way in the 1970s. Hardee's opened earlier to serve egg-based dishes and biscuits around the same time that McDonald's introduced the Egg McMuffin. Regional chain Burger Queen was right behind, holding onto a mornings-only menu of traditional favorites and breakfast sandwiches through its conversion into Druther's in the early 1980s.

As fast food breakfast continued to grow and prove profitable for the chains that offered it, Dairy Queen wanted in on that lucrative market sector. Rather than develop an entirely new menu segment from scratch, executives looked to the upper Southeast and lower Midwest, where dozens of Burger Queens had transformed into Druther's and then turned into Dairy Queen restaurants. The breakfast menu at Dairy Queen locations in and around Kentucky thus became the basis for the company's nationwide breakfast menu. Not all DQ restaurants serve breakfast in the 2020s, but those that do started with the template laid out by Druther's and Burger Queen in the '70s and '80s.

There's just one outlet left

Once a 200-location-plus strong chain of restaurants centralized in the eastern United States, Burger Queen would utterly disappear, but first, only in name. In 1981, the company became Druther's, and about a decade later, through various deals and arrangements, the majority of its restaurants became Dairy Queens. What remained of Druther's started to die out in the 2000s and beyond, and as of 2023, there's only one entry left in what used to be a large network of restaurants.

The final Druther's Restaurant stands in Campbellsville, Kentucky. Like the earliest outlets of Burger Queen that opened for business in Kentucky, Druther's operates in a county seat and services the surrounding areas. The contemporary menu of this Druther's isn't too different from the bill of fare offered by Burger Queen. It sells industry-pioneering breakfast items, as well as fried fish, and a variety of burgers (including the Big Mac clone, the Royal Burger). The signature selection at the no-longer burger-first restaurant is chicken, much like what the original Burger Queen drive-in sold in Florida back in the 1950s.