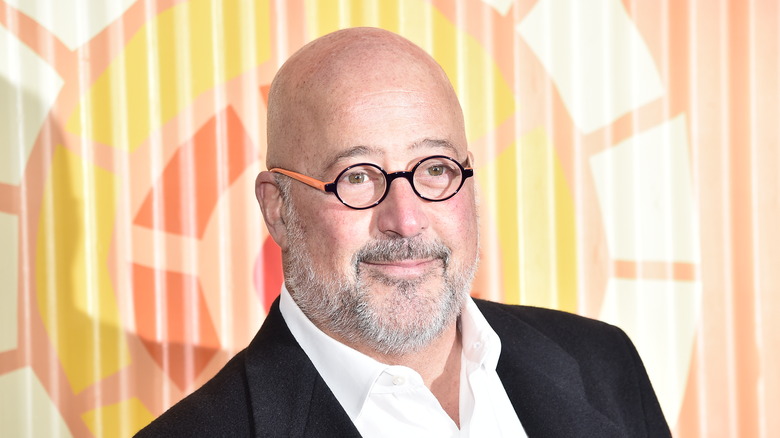

Tragic Details About Andrew Zimmern's Life

Andrew Zimmern got his big break in 2007 as the "Bizarre Foods" guy on the Travel Channel. He was a natural host, smirking at a beating cobra heart before popping it into his mouth like an almond or advising us to skip the starfish course and go straight to the jellyfish. When you watch Zimmern globe-trot his way through marketplaces and village eateries, giggling over bull testicle ceviche and educating us on the finer points of head cheese, it's hard to imagine that this eloquent adventurer was once a homeless criminal crippled by alcohol and drug addiction. But he was.

The story of Andrew Zimmern's life is characterized by a massive fall from grace and an even bigger redemption. The tragic details of Zimmern's life weren't always public knowledge, but as his star in the media began to rise, he felt a duty to be open about the struggles he went through. "Bizarre Foods" stopped filming in 2018, yet the cancellation of his landmark T.V. show was just a bump in the road for Zimmern, whose trials and tribulations before fame were sometimes a literal matter of life and death. Zimmern would go on to film more shows and retain his celebrity status but, more importantly, he continues to be a voice for those who battle addiction and mental health issues. These are some of the tragic details about celebrity chef Andrew Zimmern's life.

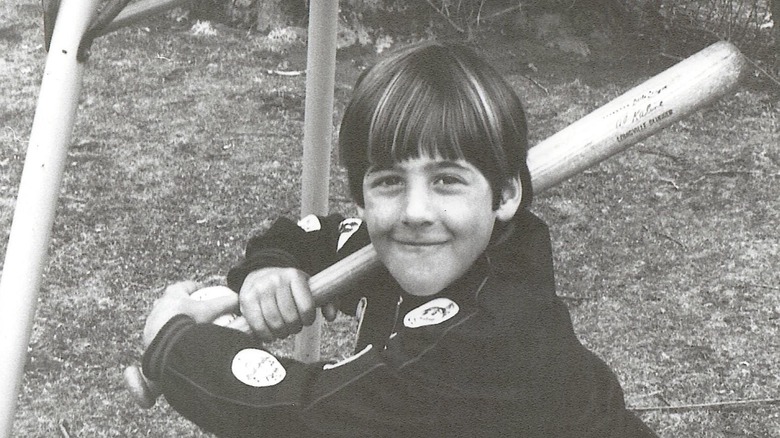

He struggled with his mental health in childhood

Zimmern was born in the Upper East Side of Manhattan. What sounds like an auspicious beginning was complicated due to Zimmern's less-than-traditional family life. His parents were best friends who married and had a child despite Zimmern's mother being aware of her husband's homosexuality. When Zimmern was about five years old, his father decided to live as an openly gay man. Zimmern's parents subsequently divorced.

When speaking to "The Hilarious World of Depression" podcast he recalled, "I think the depression and the mental health issues, even though I didn't know what they were [...] probably when I was five, six years old" resulted in significant behavioral issues like compulsive, risk-taking behaviors that foreshadowed what was to come. He liked shoplifting, for instance. As he told "The Hilarious World of Depression," Zimmern would steal "bunches of things, only bunches of things satisfied me, like I would steal a bag of a thousand fish hooks."

These compulsions also involved drinking. In an interview with "Back From Broken" Zimmern talks about sipping "my dad's drinks when I made them for him because I loved the taste of the Scotch and soda," though he believes that it was more about the naughtiness of the act than the alcohol itself. "I was addicted to the sneakiness and the lying before I was addicted to how the booze made me feel," Zimmern admitted.

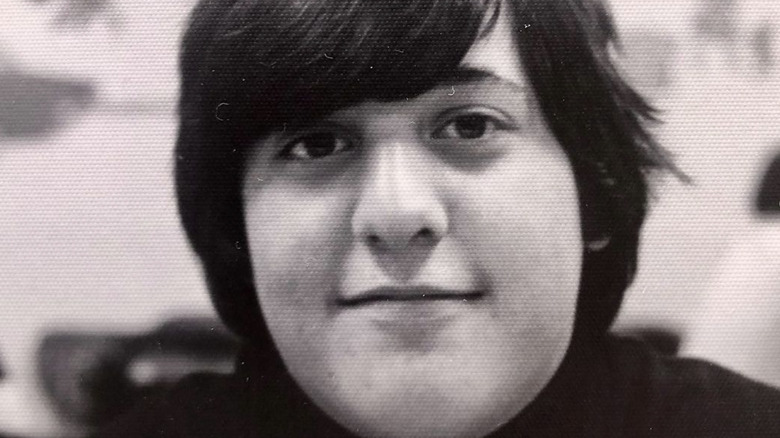

Zimmern's mother suffered a medical tragedy when he was young

After Zimmern's parents split, he lived with his mother and saw his father on the weekends — a typical routine for a child of divorce — until a tragic accident changed everything. In the summer of 1974, Zimmern, then 13, came home from sleepaway camp to learn his mother was in a coma. Because the wrong anesthesia was administered, her oxygen flow failed and she sustained serious brain damage.

Zimmern reflected on the incident to Artful Living, "At 13, I walked into this room and saw my mom in a plastic oxygen tent. It was an extremely traumatic event in my life, one that has affected me greatly up until even a couple years ago."

When she came out of the months-long coma, Zimmern saw the full extent to which her state of mind had been altered. As he revealed on the "Back From Broken" podcast, "She spent years in hospitals, mental health clinics trying to get right. Instead of dying, where there could be an opportunity to complete a grieving process, the mother that I knew the first 13 years of my life — she was gone and she was replaced by someone else." While he had been away at camp, Zimmern tried marijuana for the first time. To cope with his mother's challenges, he would again seek solace in substances. It was the beginning of a dangerous road for the vulnerable teen.

His addictions to alcohol and drugs began early

As a child in the 1960s, Zimmern flirted with alcohol in grade school but says it wasn't until he was around age 10 that he got drunk for the first time. By the onset of his teens and in the wake of his mother's medical tragedy, Zimmern was often left unsupervised at home. In an attempt to quell his confusing feelings of anxiety and sadness, he began to dial up his drinking and drug use.

At 13, Zimmern used the family credit at the liquor store to keep himself stocked in alcohol and even dipped into his mother's emergency cash fund to buy alcohol and drugs. By 15, he was smoking marijuana and snorting cocaine before school. "It was the beginning of what became my love affair with speedballing," he said on "The Hilarious World of Depression" podcast.

Zimmern eventually began dealing drugs and relying on a daily cocktail of marijuana, cocaine, alcohol, and pills. He was able to maintain good grades, but before he had even graduated high school he'd experimented with heroin. In college, he studied history and art history but often took semesters off due to his intensifying addictions. When he wasn't in school, Zimmern traveled abroad to study cooking, learning from chefs in Italy, France, and Hong Kong. Even in the mire of substance abuse, Zimmern was able to express his passion for food.

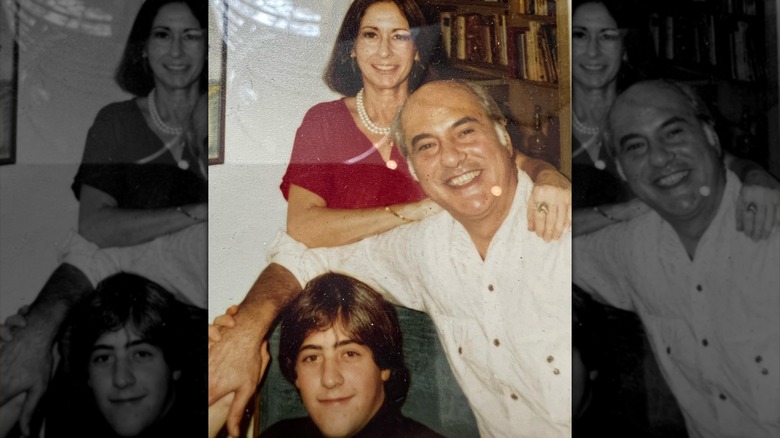

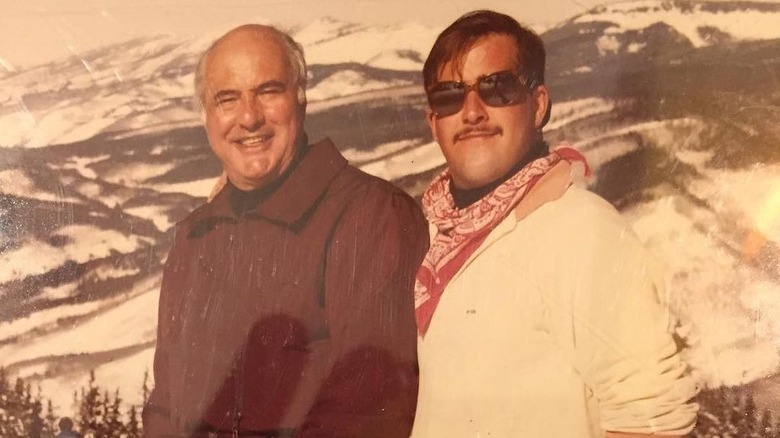

He had a complicated relationship with his dad

As Zimmern said in a conversation with the podcast "Eat My Globe," his father "lived to eat and ate to live and traveled to eat and ate to travel." Young Zimmern often accompanied his father, an advertising executive, on international business trips. When they weren't continent-hopping and digging into exotic fare, his father kept company with a prestigious circle of foodies that Zimmern referred to as a "gay food Mafia in the West Village" that included the renowned chef James Beard. In his youth, Zimmern frequented Sunday brunches at Beard's home.

Although Zimmern's father was pivotal in inspiring the youngster's cultural curiosity surrounding food, their relationship had its difficult points. When Zimmern's mother fell into a coma, his father didn't take him in. Instead, the 13-year-old lived alone in his mother's apartment — a nanny and a housekeeper were the only ones looking after him. Zimmern summed up the complicated scenario on "Back From Broken": "My father continues to this day to be my hero. I have him on a pedestal. It took me 25 years into sobriety to get to the point where I could admit that that day when my father dropped me off at the apartment that he abandoned me."

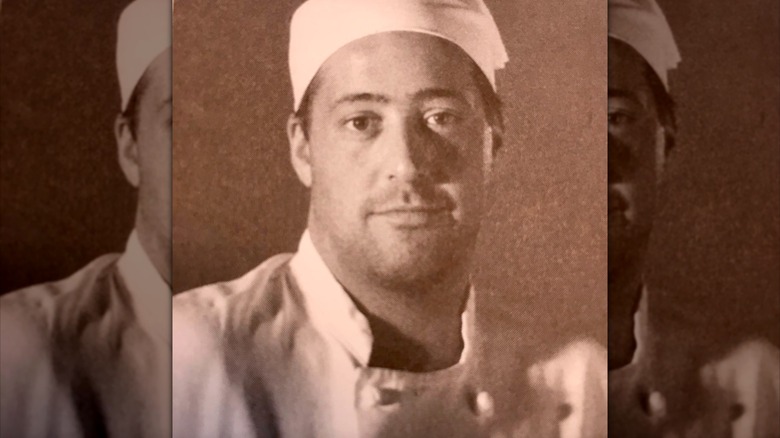

A once promising career went down the drain

Through the ups and downs of Zimmern's young life, one constant was his infatuation with food. He grew up cooking with his mother and grandmother and spent summers working his first job at a seafood restaurant on Long Island. After graduating from Vassar College in 1984, Zimmern plunged into the New York City fine dining scene. He rose to prominence as a chef before becoming a restaurateur and partner in a food service development and consulting group. All the while, he dealt with severe drug and alcohol addiction, to the point where Zimmern admits that he doesn't remember most of the 1980s.

He does recall the schemes he ran to fuel his all-consuming substance dependency. In an interview on the "Heart of the Matter" podcast, Zimmern said, "I knew with the old NCR2160 cash machines, and my manager's code, and my little key that I could play games with the register and be pocketing $100.00, $150.00 cash from each one and making a tidy little sum to support my drug habit."

For a while, he got away with both this con and an addiction that had him falling asleep in restaurant bathrooms. "I used heroin to come down from coke, alcohol to moderate the pills. I had it all figured out," he wrote in a piece for Guideposts. Until he didn't.

For a year, he was homeless

By the early 1990s, Zimmern could no longer hide his addictions, yet he wasn't ready to quit. He was evicted from successive apartments, while his relationships with friends and family hung by a thread. Then, one of Zimmern's consulting clients found Zimmern passed out on the floor. His partners fired him.

Zimmern went to a bar and encountered a group of squatters whom he followed back to the abandoned building in Lower Manhattan where they lived. Zimmern spent about a year there. By day, he stole unattended purses in upscale bistros and sold their contents to buy alcohol and drugs. After dark, he staked out nightclubs. When a drunk man in a nice suit stumbled out alone, Zimmern would ambush him and run off with his wallet.

At the squatter's den, Zimmern slept on a pile of dirty clothes on the floor. He shoplifted Comet cleaner from a bodega and sprinkled it around his sleeping place to ward off rats and cockroaches. He never bathed. Looking back on this desperate time in his life, Zimmern said on the "Back From Broken" podcast, "I just can't imagine doing that today. It's beyond my comprehension. And yet I did it. And the reason that I did was that I believed with every ounce of my being, I did not have a choice. There was no choice. I had to do it."

A suicide attempt was the turning point in his life

Plagued by defeat and overcome with shame, Zimmern's breaking point came in early 1992, when he stole jewelry from his godmother and sold it for $200. With the money, he booked a room at a flophouse called the San Pedro, bought two cases of Popov vodka at the liquor store across the street, took them to his room, and ripped the phone jack out of the wall.

Zimmern drank almost continuously for about four days until an unexpected moment of clarity came over him, which he revisited on the "Let's Talk Addiction & Recovery" podcast. "For the first time since I was 7 or 8 years old, I didn't have that Ace bandage of pressure around my chest," he said. "I didn't have the anxiety that I experienced during every waking moment of my life when I wasn't medicating myself. And for whatever reason I did something that I had never done before in my whole life which was ask another human being for help."

He plugged the phone back in and called his friend Clark, who brought Zimmern to his home to bathe and sober up. While Clark was at work, Zimmern drank all the alcohol in the home and stole his friend's change to buy more. What Zimmern didn't know was that Clark had already helped plan his intervention and rehab.

After rehab, he had to start all over

In 1992, Andrew Zimmern touched down in Minnesota, courtesy of a one-way ticket and an open bed at Hazelden, a respected rehab center in the Twin Cities. Zimmern worked through his 12-step recovery program and after five weeks in treatment, transitioned into a halfway house where he was expected to get a day job. He started working as a dishwasher at Dubins Café in St. Paul, and to this day considers it the best job he's ever had, as he told Tasting Table.

His next gig was as a busboy at Cafe Un Deux Trois. By the time he moved out of the halfway house, Zimmern was the restaurant's executive chef until 1998, when he left his post to seek new opportunities. When his ventures didn't materialize the way he'd hoped, a sober and ambitious Zimmern set his sights on food media. He started local, with food reviews and short-form T.V. segments. Eventually, his pitch for "Bizarre Foods" was picked up by Travel Channel. The show would become one of the most lucrative for the network and rocket Zimmern to celebrity status.

Bizarre Foods was canceled due to Zimmern's tone-deaf remarks

Zimmern continues to work the steps of his recovery program and has been sober since the day he set foot in Minnesota, where he still resides. "Bizarre Foods" and its spin-off "Bizarre World" brought Zimmern continued success, at least until a few ill-worded quips during a 2018 interview with Fast Company caused a blip on what had been a smooth path for the popular T.V. host. The interview, which took place at the 2018 Minnesota State Fair, seemed lighthearted enough. But when talk turned to Zimmern's latest project, a soon-to-open Chinese restaurant called Lucky Cricket, the conversation got awkward fast.

In an attempt to vividly illustrate his goal of opening 200 Lucky Cricket establishments in middle America, Zimmerman described himself as an "entrepreneur with a soul" who wanted to "make the world a better place". Okay, fair, but then he capped that sentiment off by saying, "I think I'm saving the souls of all the people from having to dine at these horsesh** restaurants masquerading as Chinese food that are in the Midwest."

The backlash was almost instantaneous. Zimmern took to Facebook to address his blunder and apologize to the Chinese American community. Filming halted midseason on "Bizarre Foods" and another show of his that was being produced at the time, "The Zimmern List." The ultimate cancellation of "Bizarre Foods" put an end to Zimmern's 12-year "Bizarre Foods" legacy that spanned 199 episodes.

His restaurant closed after just eight months

Whether Zimmern's controversial comments were the cause of his restaurant woes is hard to say. Lucky Cricket opened in St. Louis Park, Minnesota in November 2018. The 200-seat establishment, which specialized in tapas and shareable plates, had a tiki bar and tuk-tuk vehicles imported from China. But food journalists can be extra-critical of celebrity-owned restaurants and, in light of Zimmern's controversial Fast Company interview, skepticism was unavoidable. This was the place that was supposed to rescue midwesterners from supposedly bad Chinese food after all.

Reviews ranged from positive, to questionable, to cutting. The kitschy decor and inconsistencies in food quality were common call-outs. Things seemed to be going okay for Lucky Cricket, but by July 2019, the restaurant closed its doors. Despite only being open for eight months, Lucky Cricket claimed the closure was due to renovations. Nearly two months later, the restaurant reopened with a rebooted menu that included Vietnamese and Korean-inspired dishes. The bar's tiki theme was toned down, yet Zimmern's insensitive remarks about Chinese American dining still followed him in the press.

Lucky Cricket closed a second time during the COVID-19 pandemic and never reopened. There is currently no mention of the restaurant on Zimmern's social media pages, while the restaurant website was scrubbed from existence. In 2021, the owners of the West End plaza where Lucky Cricket operated sued to evict the restaurant, stating that it owed $705,000 in back rent.

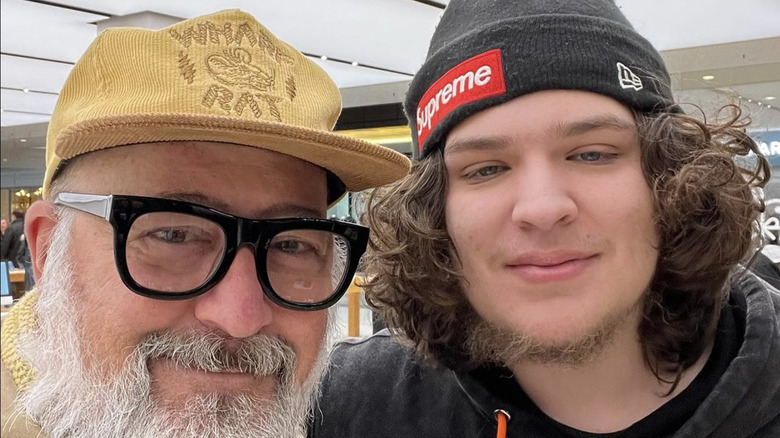

He referred to his wife and son as victims of his popularity

In the years that Zimmern was filming "Bizarre Foods", he visited over 170 countries and traveled 250 days out of the year. When he wasn't on location for "Bizarre Foods", Zimmern's schedule was full of public appearances and other events, leading to a popularity and time away that was difficult for his family.

To make matters more complicated, Zimmern has been open about developmental challenges faced by his son Noah, who was born in 2005. In 2014, Zimmern told Mpls.St.Paul, "Two and a half years ago, our family was in crisis," and thanked The Washburn Center For Children in Minneapolis for implementing a treatment plan that involved the whole family. Yet the demands of his job persisted.

Amidst the mounting pressures of his fame and reputation, Zimmern felt he had no choice but to fulfill the many obligations that came with celebrity. He addressed the difficulty in MinnPost saying, that his family members "are victims of my popularity [...] I'm sure more days than not they would say it's not worth it, but I have this business to support."

He divorced after 16 years of marriage

Zimmern met his wife Rishia Haas at a cooking school in 1999, where he was teaching and she worked in the shop. When they married in 2002, Zimmern had years of sobriety under his belt but wasn't famous yet. Although Zimmern often commented in the press about how his demanding job didn't make family life easy, what the public didn't know at the time was that it was also wearing his marriage down.

In 2018, around the time Zimmern was preparing to open his restaurant Lucky Cricket, he was also in the midst of a separation from his wife. Zimmern confronted the media's inquisitions about his relationship issues without airs, telling The New York Times in September 2018, "I wasn't there for my wife, and I wasn't there for my son. My wife gave me a thousand chances to make it right." By March 2020, the divorce had been finalized.

Though his marriage dissolved and his demanding schedule shows no signs of letting up, Zimmern has found peace in these challenges. He is a devoted father, vowing to The New York Times to "be the best dad and the best ex I can be."

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues or is struggling or in crisis, contact the relevant resources below:

-

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

-

Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org