Everything You Need To Know About Caribbean Black Cake

The holidays mark the return of many food-related traditions around the world, whether it's the creamy, boozy coquito cocktail in Puerto Rico or the dense, fruit-filled stollen bread in Germany. Many of these recipes only appear during the holidays and require extensive time in the kitchen and ingredients that might only be available at certain times of the year or in certain parts of the world. For example, black cake is a holiday fixture throughout the Caribbean that is practically synonymous with Christmas, community, and celebration.

Originating from the harsh colonial era of the 1700s, black cake has an extensive history that is deeply intertwined with the region where it was created. Recipes for the dessert vary from island to island and family to family, but in essence, black cake is a decadent creation made with alcohol-steeped fruits, spices, and burnt sugar, which gives it its deep color. With its high alcohol content, dense texture, and intense flavor, it's a dessert meant to be shared with friends and family throughout the holiday season.

It's no small feat to make either, and many home cooks begin the process weeks or months in advance. As such, this cake is a labor of love that conjures nostalgia for many Caribbeans across the world when the festive season rolls around. Here is everything you need to know about this unique dessert, from its fraught origins and painstaking preparation to its enduring influence in literature and beyond.

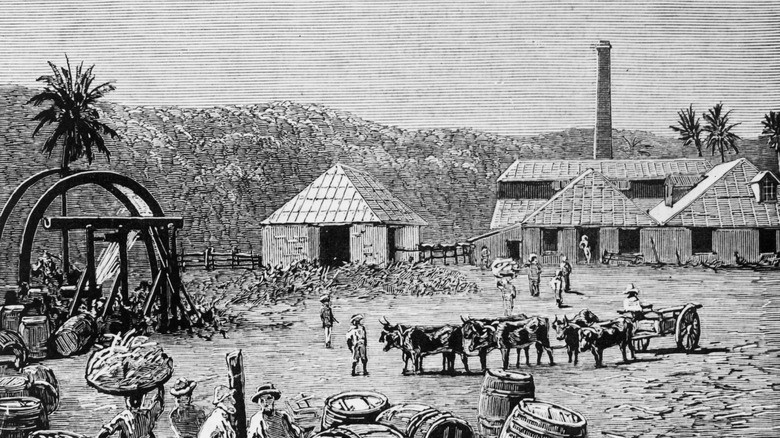

Its origins go back to colonialism

In the 17th century, the Caribbean was at the center of the transatlantic slave trade. Capitalizing on Europe's hunger for sugar, British colonizers trafficked enslaved Africans to the islands and forced them to work on newly established sugarcane plantations. At home, the British poured this sugar into their food, including the ubiquitous Christmas dessert known as figgy pudding (or plum pudding). The country viewed this booze-soaked, fig and plum-free steamed cake as a shining example of its supposed supremacy in the world. With sugar from the West Indies, spices from India, and fruit from Australia, it was a demonstration of its colonial tyranny in one sickly sweet, liquor-drenched package.

As late as 1927, the British royals were using figgy pudding as an advertisement for colonialism, though by that time the Crown had rebranded its ongoing international exploits as imperialism. That year, King George V and his family enjoyed figgy pudding as part of an effort to bolster the case for the Empire, making sure to highlight all the ingredients that had been plundered from its former colonies (per Old Royal Navy College). Although figgy pudding recipes in the U.K. haven't changed much since the 1700s, the dessert's composition was forever transformed outside of Europe when the British and their Irish servants brought the recipe to the West Indies in the 18th century.

The dessert is unmistakably Caribbean

It's no secret that British food has a reputation for being, shall we say, uninspiring. From baked beans on toast to boiled eels, the country has historically demonstrated a knack for dishes that lack flavor and sound unappetizing. But the inhabitants of the Caribbean islands saw potential in the colonizers' Christmas pudding, and with some ingredient swapping and baking finesse, they alighted on a recipe that is, without a doubt, a different dish altogether from the dessert that inspired it.

To begin with, the islanders added rum instead of whisky or brandy and decided to dice the dried fruit thinly. They also added tonka beans, which have a flavor reminiscent of vanilla, but with a rich, spicy edge and a hint of almonds. Regular sugar was swapped for burnt sugar, giving the cake its distinctive color. The sweet, lightly bitter ingredient is made by heating sugar until it becomes a dark syrup and then adding boiling water to keep it pourable. It is used in both savory and sweet dishes and provides a deeper flavor than regular sugar. Molasses is now a frequent substitute, though its flavor is not a perfect match.

These alterations gave black cake its own flavor and appearance, and though it may often be compared to plum pudding, everything from its texture to its taste sets it far apart from its British counterpart.

It's boozy

Black cake starts with alcohol, but rather than simply dumping rum straight into the batter, the liquor is used to steep the dried fruit to soften and infuse each piece with flavor, ensuring that every bite of the cake is of uniform intensity. Rum is the traditional liquor used, but many recipes call for a mixture of different types of alcohol, including cherry brandy and red wine. Some recipes also require the steeping liquid to be blended into a paste with the fruit rather than being drained off. As a result, one cake might contain multiple cups of alcohol, turning the already dense texture of the dessert into something resembling a creamy pudding.

The high liquor content also plays a key role in the cake's impressive shelf life. For one thing, it stops you from eating more than one or two small pieces at a time, and for another, it acts as a natural preservative. If you douse the cake in alcohol once a week, it can last up to several months without going bad, giving you an excuse to continue celebrating the holidays, a wedding, or whichever festive occasion you're honoring. When following a recipe that calls for draining the fruit after the steeping process rather than blending it into the batter, make sure to save the liquid. Boozy and fruit-filled, it may as well be liquid gold. You can pour it over the cake after it's baked or add it to cocktails.

The preparation can take months

Time is one of the most fundamental ingredients in black cake. Many cooks start soaking the fruit in alcohol six months before the holidays. There are no rules about which dried fruits should be used, but common mixtures include raisins, currants, cherries, and prunes. Some recipes call for candied ginger and papaya as well. The soaking process, known as maceration, rehydrates the fruit so it softens and expands while drawing its flavors into the alcohol. The result is a unique, complex taste that is the secret to the cake's appeal.

The timing of the maceration process varies from person to person, but for many cooks, the end of hurricane season in the Caribbean (around September or October) marks the beginning of the preparation. For others, the process is much longer, up to a year in some cases. The longer the fruit macerates, the more alcohol it absorbs, especially if the fruit is purchased fully dehydrated. If you are opting to start early, you might need to top up the liquid every so often as the fruit absorbs it. Although some recipes offer seemingly efficient workarounds by directing you to heat the liquor and fruit in a saucepan before letting it sit for a few hours, this will not achieve the same depth of flavor as months of steeping will. Nothing can substitute the planning and time that go into the process.

There are variations throughout the Caribbean

Wherever you are in the Caribbean, black cake is likely to be a favorite holiday dessert. After hours of patient, hands-on work in the kitchen, friends and family enjoy it together as a gesture of love and closeness. But depending on which island you're on or even the household, the recipe varies.

In Trinidad and Tobago and Guyana, for example, it's common to use cherry brandy as the alcohol of choice, while in Jamaica, red wine or white rum are often used instead (usually together). In St. Lucia, you'll see a mixture of Caribbean rum, including white, dark, and spiced varieties. In Jamaica, the alcohol used to steep the fruit is often enhanced with rosewater.

Most recipes call for the fruit to be chopped finely in a food processor before soaking in alcohol, but while some cooks transfer the fruit directly to the batter after steeping, others blend it into a paste. With more moisture than drained fruit, this paste gives the cake a gooey, dense, and almost creamy texture.

It has become a fixture of Christmas and wedding celebrations

Like mooncakes and panettone, black cake is more than just a sweet treat; it is an integral part of significant celebrations. In China, mooncakes symbolize family and prosperity during the Mid-Autumn Festival, while panettone is inextricably linked to Christmas time in Italy. In the Caribbean, black cake is the go-to dessert for the biggest celebrations of the year and in life, especially Christmas and weddings.

It isn't clear how black cake became a Christmas staple in the Caribbean. Its predecessor, figgy pudding, became associated with the holidays in England in the early 18th century when King George I put it on his Christmas menu, which likely played a role. But there is a simpler reason why it is reserved for special occasions: It is a labor of love. The time, money, and work that go into each cake is well known, and anyone lucky enough to be gifted with a slice of it recognizes the sacrifice that went into its creation. When black cake is presented at Christmas, weddings, and christenings, it's a testament to the importance of these occasions and the respect, care, and communion they call for.

The cake sometimes has icing

Black cake is known for its distinctive color, a deep brown that is so dark it could be mistaken for a chocolate or espresso-flavored dessert. In many households it remains unadorned, with its striking color and shiny appearance from the alcohol on full display. The lack of icing is also a practical decision because it makes it easier to soak in liquor from time to time to preserve it. However, some bakers, especially in Guyana, add white icing to the recipe, giving the cake a snowy coating and bold color contrast.

The recipe is usually a variation of royal icing, a mixture of powdered sugar and egg whites, or meringue powder and water. Adding vanilla extract, almond extract, or lemon juice will infuse flavor, but black cake is already so delicious that these are unnecessary. Because the cake contains a good amount of moisture, it's important to put a barrier between the icing and the cake to prevent the icing from absorbing the dark liquid and turning brown. Almond paste is traditional, providing yet another layer of flavor.

It used to be made without ovens

These days, black cake is prepared in much the same way as other cakes, aside from soaking the fruit for months. However, one common thread in these recipes stands out. Rather than heating the oven to 325 or 350 F, as is typical for everything from brownies to banana bread, black cake is baked at a much lower temperature, usually around 250 F. The reason likely lies in the earliest days of the dessert, when households were not equipped with modern kitchen amenities.

Clay or iron coal pots were commonly used in the West Indies in the 18th century. Often heated over open fires, they provided a slow and even baking process that must have contributed to the dense, moist texture of black cake that is now one of its hallmarks. Box and brick ovens were also widely used, but eventually, cast iron stoves were introduced, more closely mimicking a modern gas or electric oven. Still, the merits of baking black cake at a low temperature were not overshadowed by the efficiency of these new appliances. Coal pots and box ovens are no longer widely used, but baking black cake at a low temperature remains the preferred method.

The recipe calls for pricey ingredients

Aside from the time and planning that go into making black cake, the price tag ensures that the dessert is reserved for special occasions. On the face of it, you wouldn't think that a homemade cake would break the bank, but black is full of ingredients, and many of them have a much higher price point than flour and sugar.

For starters, alcohol is not cheap. A cheap bottle of rum costs about $10, while cherry brandy will likely set you back much more. Since alcohol is, in many ways, the featured ingredient in black cake, you may well choose to buy higher-quality options, which could easily soar to $30 per bottle or more. Dried fruit can also be expensive. Many recipes contain four or more varieties, and when you account for at least a few dollars per bag, it quickly adds up. In the Caribbean, dried raisins, cherries, prunes, and currants are more expensive than they are in the U.S., making them more of a luxury ingredient than an everyday snack.

Most significant of all, however, is the volume. Black cake is densely packed with ingredients, and because it's often shared with family and friends throughout the holidays or during big celebrations, most recipes make two cakes. With the number and quantity of ingredients, black cake would be expensive to make even if it only involved affordable pantry staples.

Don't mistake it for American-style fruitcake

Just because black cake contains dried fruit does not mean it should be compared to American or British-style fruitcakes. For one thing, it isn't particularly polarizing. In the U.S., fruitcake is a notorious Christmas stalwart that most people would be thrilled to never see again. Black cake, on the other hand, is a beloved emblem of Christmas that conjures nostalgia and cravings from just about anyone who's tried it.

There are several reasons why this Caribbean staple does not draw the reaction that its American and British counterparts do. For one thing, the fruit in American fruitcakes is often hard enough to make your jaw sore and your dentist shudder, but the fruit in black cake is lightly pureed before being soaked for months in alcohol, making it buttery soft. Some recipes take it a step further by blending the fruit and alcohol into a paste, eliminating the danger of loose teeth.

Other ways that black cake differs from fruitcake include the color and flavor of burnt sugar, the copious amount of alcohol (some fruitcakes do not contain any), and its dense, moist texture (fruitcake somehow manages to be both dry and gummy). Black cake often contains vanilla and almond extract or the mysteriously named "essence," all of which act as stand-ins for the traditional tonka bean paste. They may both be cakes made with dried fruit, but fruitcake and black cake are miles apart in almost every other way.

It was a staple in Emily Dickinson's household

One of the strangest twists in the history of black cake is its association with the 19th-century American poet Emily Dickinson. Over time, Dickinson has attained an almost mythical status for her reclusive nature, but in reality, she was a highly sociable figure in her New England town and was known to her friends and family as an avid baker more than a poet. One of her most treasured recipes was for black cake, which she included in a letter to her close friend, Nellie Sweetser. Dickinson's recipe calls for 19 eggs and five pounds of raisins, and weighs about 20 pounds when soaked in brandy, suggesting that she distributed it as a gift to her friends and acquaintances.

Where Dickinson acquired the recipe is something of a mystery, though it reflects the unsavory realities of 19th-century life in America when slavery was still very present. Dickinson is known to have hired Black servants in addition to Native American and Irish ones, but there is no record of whether any of them provided her with the recipe. However, the cake has become associated with her over the years and even played a prominent role in an episode of the lighthearted Apple TV+ series "Dickinson," in which she presents it at a baking competition.

A novel was named after it

Black cake has had more moments in the literary spotlight since Emily Dickinson's recipe came to light, most notably in a novel by Caribbean-American writer Charmaine Wilkerson. Published in 2022, "Black Cake" tells the story of two estranged siblings who receive an unusual inheritance when their mother dies — a black cake in the freezer and a voice message that reveals a family secret. For Wilkerson, whose Jamaican mother was renowned for her black cake, the dessert represents more than just a festive recipe; it symbolizes everything from family bonds to the evolution of cultures and memories (via Eater).

The novel was a bestseller and led to an on-screen adaptation in 2023 on Hulu. Reviewers praised the show's nuanced depictions of identity, memory, secrecy, and the power of food to build a bridge between the past and present. Both the novel and the series demonstrate that black cake is not just a delicious recipe that features heavily in celebrations throughout the year, but a powerful emblem of resilience, history, and family.