False Facts You Believed About Christmas Pudding

Christmas food traditions vary greatly from country to country and even family to family, but some stand out as classics that most people are familiar with. The British Christmas pudding is one of these; even if someone's never actually eaten one, they've likely heard of it or its companions, figgy pudding and plum pudding. If they've done any reading of Dickens at all, they'll recognize pictures of the round, steamed cake with a holly sprig at the top.

When someone grows up only hearing about a particular food and not actually eating it, myths and false facts about that food can abound. Christmas pudding is no different. The false facts can be tricky to deal with as much of the time, they're really just old facts that are no longer valid, or they're true in some regions and just not true in others. Some are misunderstandings that could even have disastrous effects if you were to try to make your own Christmas pudding. If you plan to bake your own this Christmas, read over these false facts to ensure you know what to expect.

False: It contains meat

People outside of countries where Christmas pudding is common sometimes think the pudding contains meat. This actually used to be true; the original forms of Christmas pudding contained a mixture of meat (often beef and mutton), fat, vegetables, grains, and fruit, often wrapped up in something like animal intestines or stomachs as a sort of sausage. There was even a dish called "plum pottage" in the 15th century that was a mix of meat and vegetables served as an appetizer of sorts. Meat left the ingredient list for the most part around the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century.

However, associations between Christmas pudding and meat still persist because some Christmas pudding recipes contain mincemeat. Mincemeat is a mixture of dried fruit, citrus peel, spices, sugar, and alcohol, and like Christmas pudding, it used to contain meat a long time ago, hence the name. It's now a sweet filling used in pies, and because its ingredients are similar to those used in Christmas puddings, it's often included in modern quick pudding recipes, such as those made in the microwave. In any event, neither Christmas pudding nor mincemeat now contain ground or cut meat.

Mostly false: It's a vegetarian dish

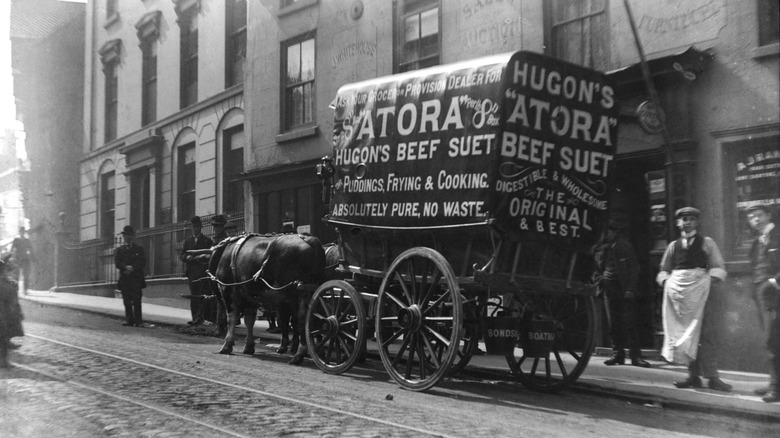

So, it's false to say that Christmas pudding contains meat. However, that doesn't make it vegetarian. While the recipes no longer add meat or stuff the filling into an animal stomach casing, standard Christmas puddings do use beef suet, a kind of saturated fat found around animal kidneys. It's kind of like fries made in beef tallow; you wouldn't say they contained meat, but you wouldn't consider them vegetarian.

If you want to cook a plant-based Christmas pudding, you should be able to find vegetarian suet pre-packaged in U.K. supermarkets (and, we assume, supermarkets in any country where suet is commonly used). Another substitution is vegetable shortening that's been frozen and grated, which is a great option if you're in the United States and can't get your hands on actual suet. If you're determined to make a traditional Christmas pudding and want beef suet, though, check with a butcher or order online. By the way, while you can find suet in the U.S. in bird seed mixtures and cakes made for bird feeders, you don't want to use that for your Christmas pudding.

False depending on who you talk to: It has plums and figs in it

Depending on who you talk to, Christmas pudding — which is also called figgy pudding and plum pudding, and we'll delve more into that later — contains figs. Or it contains plums. Or it contains neither because those terms have older definitions that don't mirror their modern meanings. Probably the most false part of the initial claim is that the pudding contains plums because it usually doesn't contain actual juicy plums. It can contain prunes, and while a prune is a dried plum, the textures of the two are completely different even after cooking. "Plum" was also used long ago to refer to dried fruit in general, sort of like how "Coke" can mean any type of cola no matter the brand in some regions of the U.S. Despite not having actual plums, the name stuck. "Plum" could also refer to raisins, which are very common in Christmas puddings now.

Figs are another matter. Sometimes the dried fruit mixture in Christmas pudding contains dried figs along with several other types of fruit. This is a matter of personal preference, so some Christmas puddings may not have any figs in them at all. And sometimes, as food historian Ben Mervis told Better Homes & Gardens, "figgy" can refer "not to the actual fruit itself but the fact that the pudding is flecked with dried fruit."

False in many places: You might find a silver coin in your slice

Mardi Gras has its king cake with the hidden plastic baby doll, and Christmas has its pudding with a silver coin wedged somewhere inside, or so people think. It's true that there's an old tradition — which many people still follow — of sticking trinkets into Christmas puddings. These included a silver sixpence coin, and the person who got the silver coin in their slice had a supposedly lucky or wealthy year ahead of them.

But this tradition is turning into a false fact in some regions. Australians used to place a silver coin in their Christmas puddings, but when the materials used to make their coins were changed from silver to base metal in 1966, the new coins turned green in the pudding and tainted the flavor. Not the most auspicious thing to see in something that you're eating, so Australians have pretty much dropped that tradition. In other areas, people are shying away from adding coins because of hygiene concerns; coins aren't the cleanest things around. There's actually a myth that putting coins in Christmas puddings was banned for health and safety reasons, but that isn't true, either. And as writer Robert Hume warned in the Irish Examiner, you don't want a slice of pudding with a coin going in the microwave. As disappointing as it might be to not find money in your Christmas pudding, the omission is for good reasons.

False: It's just a type of fruitcake

Christmas pudding is an alcohol-soaked cake with dried fruit, fruitcake is also an alcohol-soaked cake with dried fruit, so a Christmas pudding is just another version of a fruitcake, right? No. They are initially similar, yes, but the basic description is about it. From there, they diverge.

Fruitcake is a cake that you mix together and bake, and it contains butter as its fat. It's a comparatively quick process to get the cake made. Christmas pudding is a very different animal. This is a cake that's usually steamed or boiled (but sometimes baked) and contains suet as its fat. It can take hours to cook and weeks, if not months, to age before being re-steamed, doused in alcohol, and set on fire. Also, there are versions of Christmas pudding that contain vegetables instead of fruit. You don't see U.S. fruitcakes with veggies in them, but you can find Christmas puddings made with carrots and potatoes in Canada. The original version of this was created in England in 1845, but its use today is a holdover from World War II when it was harder to get fruit and spices. The vegetable pudding appeared in Britain, too, as the Ministry of Food there tried to feed the population with whatever could be grown in the country.

False: They're just like other steamed puddings

Many steamed-pudding recipes don't take very long to make; making them is like making most other cakes, only they're steamed instead of baked. Christmas puddings are very different. While you can find recipes that let you make the puddings quickly (albeit non-traditionally), to make an actual Christmas pudding, you need to start early. Not only can the initial cooking take up to eight hours, but the storage and aging time can traditionally take anywhere from four to six weeks. Some people even start preparing the puddings around Easter, and it's not unheard of to find people occasionally slipping a little more alcohol onto the pudding as those weeks go by.

The puddings survive those weeks and months due to the alcohol. Alcohol in greater concentrations in food kills off bacteria and yeast that would normally cause the food to decay, and it's a common preservative for fruit and other foods. However, the alcohol and pudding need a while to meld, thus anyone making a traditional Christmas pudding with alcohol needs to let the pudding sit for a while in storage. While you could skip the storage and eat the pudding after its initial steaming, boiling, and baking, even that will take planning as you'll need to start several hours before you intend to serve it. If you wait until the last minute, thinking you can throw a traditional pudding together in an hour, you're not going to be very happy.

False: It's always been a dessert

Christmas pudding has changed not only in form, but in when it appears during a meal as well, transforming from a savory starter to a sweet dessert. Way back in the 1300s when it was still a mix of meat and other foods and had a less solid form than it does now, it was served at the start of a meal. When it changed into a sausage-like dish that still contained some meat, it was usually sliced and roasted underneath another piece of meat, and it could serve as both a starter and a side dish.

The timing of the switch from savory to sweet gets a little hazy here. Some sources say the switch to a more solid but still savory form happened around the end of the 1600s. However, others say it became a sweet dish at the end of the 1500s, and it was associated with Christmas by the mid-1600s. Whatever the correct timing is, by the early 1700s, the dish was a sweet dessert that England's George I requested be served at his Christmas banquet.

Could be false, according to experts: That it's a totally English dish

Most sources point to an origin for Christmas pudding in England, but there are hints that a close version may have been made in Brittany, France and even in ancient Greece. You've already learned that Christmas pudding is a descendant of pottage served in England and that its centuries-long evolution occurred in the U.K.

However, a few experts in cooking have wondered about whether the dish existed long before that in non-British regions. Elizabeth David was a British food writer who was considered one of the greatest of the post-WWII 20th century. She found that a French chef from the turn of the century, named Philéas Gilbert, had claimed that another French writer named Bourdeaux drew a connection between Christmas pudding and a Breton dish named Le Far (this may have been Far Breton, a cake with prunes, raisins, eggs, sugar, and alcohol). He also claimed that a similar food was described in an ancient Greek report on a lavish wedding. There's not much to go on here, but it would be interesting if Christmas pudding's origins were suddenly found to be French or Greek.

It depends on who you ask: It has always been a Christmas food

Christmas pudding has gone through a few iterations, the earlier of which weren't associated with Christmas. So, on one hand, the claim that the pudding has always been a Christmas tradition isn't quite accurate if you consider all those different forms to be variations of Christmas pudding. On the other hand, you could argue that those non-Christmas forms weren't really the same dish as what people call Christmas pudding today, so you could technically say that it has always been a Christmas food.

Sources are kind of all over the map on this one. Some say the pudding became heavily associated with Christmas only after Charles Dickens published "A Christmas Carol" in 1843, or after the Victorians in England began a tradition called Stir Up Sunday in the 1800s when people would each take a turn at stirring the pudding batter. Another claim is that George I made it a Christmas food when he had it served at a Christmas banquet in 1714, and still other sources place its association with Christmas in the 1600s.

False if you're not superstitious: It's supposed to have 13 ingredients

There is a belief that a proper Christmas pudding has 13 ingredients to represent Jesus and the apostles. However, many, many Christmas puddings don't contain that much. A fairly standard list of ingredients can contain 11 to 12 ingredients, not counting those used for the saucy topping that some puddings have; the sauce usually ups the total number of ingredients to something like 16.

How this false fact got its start isn't clear. It went hand in hand with a rumor that the Catholic Church decreed that the pudding must represent Jesus, but that rumor has never been proven. In this case, the pudding having 13 ingredients is true only if you decide that it should. For most people, especially those who aren't into superstitions, the 13-ingredient rule doesn't mean anything. Just be aware that if you make it and invite English friends over to try it, you could run into people who think it should always have 13.

Surprisingly false: Christmas pudding, figgy pudding, and plum pudding are all the same

Here's one that surprised even us. Christmas puddings are often called figgy pudding or plum pudding, and you'll see the three names used interchangeably. As we mentioned before, the use of the terms "figgy" and "plum" don't always refer to actual figs or prunes and plums, so calling a Christmas pudding a figgy pudding is perfectly normal, for example, regardless of whether or not the pudding contains figs.

The surprise is that some people distinguish between all three based on the proportion of dried fruit. In this case, figgy puddings would be those that specifically contain figs, and plum puddings would be those that have more prunes or raisins than other dried fruit. This doesn't seem to be a standard definition across all of the pudding-eating world, so if you're keen to have a particular type of Christmas pudding, double-check if that figgy pudding you're eyeing does contain figs, or if that plum pudding is heavy on the prunes and raisins.

False: Christmas pudding was never a thing in the U.S.

Christmas pudding isn't really a tradition in the United States. Some people do eat it, either because they've married into a British family or because their family has a longstanding recipe of its own. But these are individual cases and don't represent the country's habits as a whole. However, it's false to state that Christmas pudding was never a thing in the States at all — it and other steamed puddings used to be very common dishes up until around the beginning of the 20th century. Christmas pudding was familiar to the Puritans who came over to North America from England; however, they banned the pudding for 22 years, along with other celebratory features of Christmas. The Puritans were determined to have austere holidays.

Once Christmas pudding was unbanned, it and other puddings became regular inhabitants of dining rooms in the country until the early 1900s. Pudding was considered a mixed food, and mixed foods were considered unhealthy at that point in history in the U.S. Advocates wanted people to eat healthier by eating simple foods. Racism and anti-immigrant hatred also played a role as mixed foods like puddings were often associated with immigrants. The idea that mixed foods were bad faded as the years went by, and a few decades later, home cooks were producing the classic mixed food known as a casserole. British-style puddings had essentially dropped off the mainstream American menu.