What It Was Like To Eat At The First A&W

To know what it was like to sip a frosty mug of root beer at the first A&W stand, you'd have to travel back to a time when women wore flapper dresses, speakeasies reigned, and jazz filled the air. The chain officially opened its first location in California just before the raging 1920s began.

Roy Allen, the founder of A&W, got the recipe for his root beer from a retired pharmacist in Arizona. At the time, Hires Root Beer reigned in America — its founder, Charles Elmer Hires, had been in business for several decades and had become a wealthy man before Allen came along with his own version of the drink. Perhaps Allen dreamed of similar success. The entrepreneur couldn't have guessed that more than a century later his A&W restaurant chain would still be a household name while his main competitor — Hires Root Beer — would fade away into near oblivion.

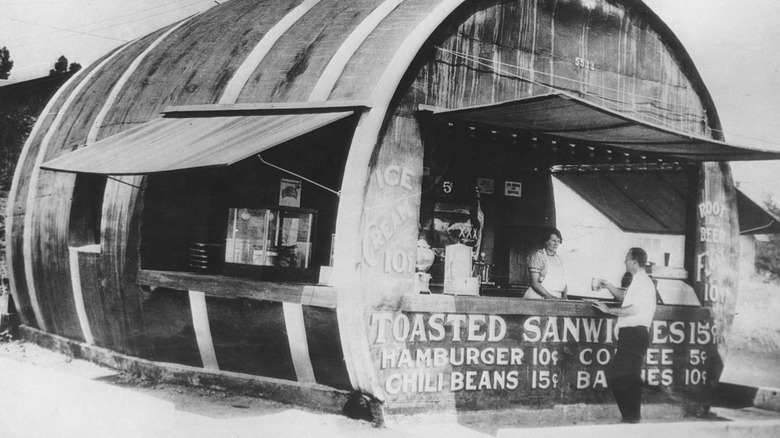

These days, eating at A&W probably means pulling up in your car, and ordering a root beer float and hamburger. The taste and texture of the root beer are not the same as they were more than 100 years ago, nor are the items on the menu the same. The way you order is different, too. If you were to go back to 1919, the year Allen sold his first mug of the soft drink, little would indicate to you that his meager root beer stand would later become the A&W you know and love today.

You'd be celebrating the end of World War I

The public debut of A&W root beer is part of a much bigger celebration. People put on their Sunday best for a homecoming parade to welcome back the men from The Great War. The place is Lodi, California, population under 5,000. It's a small, prosperous agricultural community, and the street party for the returning soldiers has everyone out on a hot June day. The crowd is joyful. It seems like the hard times have passed.

There's band music in the background, and you're tired out from the heat, the dancing, and the dusty streets. That's when you see that newcomer to town, Roy Allen, who decided to set up a stand in front of his store on Pine Street. His syrupy sweet, cool root beer is the perfect remedy, but you have to wait in line for a while to get yours — Allen's brew is such a hit with partygoers that he can't pour it out quickly enough. Of course, people love that he's giving it away for free.

The days pass, and June turns into a sweltering summer. The residents of Lodi have Allen's smooth, chilled root beer at the front of their minds. No one can forget how good it tastes. In the late afternoons, after getting home from long days in the vineyards, everyone wants to go out to buy a frosty mug of it. His shop has become the hopping, new get-together spot in town.

You might have needed a face mask

The year A&W founder Roy Allen served his first mug of root beer, an estimated 7,000 people died in California from the influenza pandemic. More than double that number had been victims of the virus in the Golden State the previous year. Going to sip a root beer with friends at Allen's Lodi stand might have felt like you were taking a risk in 1919.

Of course, as Allen's business grew in 1920 and 1921, people were likely returning to their routines and out spending money again. The previous years had been tough, and so many lost family members. Finally, it was felt safer to go out, and officials had lifted most city-wide quarantines in the U.S. This was the time for business to boom, and it did for many industries over the next decade, including beverage makers like Allen, who expanded into Stockton and Sacramento.

Things went so well for Allen post-epidemic that he decided to take on a partner, Frank Wright, who was an employee at the time. The two used the first initials of their last names to come up with A&W's name in 1922. Together, they opened root beer stands in Texas and launched the first drive-in at a location in Sacramento. By 1924, Allen bought out Wright's share of the company and continued on his own.

You might have driven to A&W in your Ford Model T

Henry Ford wanted every middle-class family to buy a car from him, and so he put his famed Model T on the market in 1908 just over a decade before Roy Allen started peddling A&W root beer. There were already seven and half million vehicles on U.S. roads by 1920, and over 50% of those registered were this build.

One of Allen's biggest successes was linking his root beer stands to the new national pastime of driving. Yes, people had cars, but not everyone was creative enough to come up with a destination. Allen provided the answer: Thirsty California drivers could pull up to one of his root beer stands, park their cars, and wait for tray girls or boys to come up to the curb with frosty mugs of root beer.

A&W stands popped up along highways throughout the U.S. This business model peaked around 1960 with about 2,400 locations — in the same year there were just 228 locations from the new upstart chain, McDonald's. Today, motorists can still visit old-fashioned A&Ws, like the one in Cortland, New York. There, you get a feel for the old days — you order from menu boards posted at each parking space, and wait for car hops to bring food on special trays that hook onto your car window. Of course, today, the majority of A&Ws have drive-throughs and indoor seating like other major fast food chains.

A root beer cost you 5¢

In 1919, you could have bought a root beer at Roy Allen's stand for $0.05. That seems like a deal even after correcting for the past century's inflation — today, Allen's menu board might read $0.77. If you want to purchase a 12-pack of A&W from Walmart today, each can will cost you about $0.41. A glass of the same beverage from a restaurant costs more.

Allen didn't sell his product for an incredibly low price, though — there was something else at play. In 1919, no one was walking around with a monstrous 32-ounce Big Gulp. In 1916, Coca-Cola had standardized a 6.5-ounce glass bottle as a serving. A modern-day can holds 12 ounces, so that can of A&W from Walmart is nearly double the size that customers in the 1920s probably would have received.

This points to another fundamental change in the way A&W serves root beer today. The smallest size on its menu is a kid's root beer, which contains 12 ounces. An adult small has 16 ounces. Either way, that's far more than the serving size Allen was pouring.

Prohibition made root beer your best option

Drinking alcohol was illegal in the U.S. from 1920 to 1933 due to Prohibition, so many people looked for alternatives like A&W root beer. This had tremendous repercussions on the restaurant industry. Most establishments depended on selling beverages to bring in earnings, and suddenly they couldn't open a bottle of champagne without getting shut down. Even longtime restaurants couldn't weather this change and went out of business, paving the way for other types of businesses.

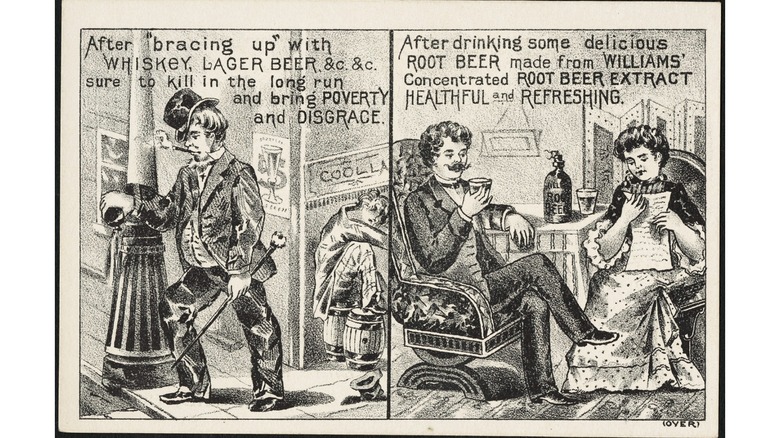

On the other hand, root beer had traditionally been advertised as an acceptable alternative to hard drinks – it contained only a slight amount of alcohol. Advertising campaigns by companies like Hires Root Beer and Williams' Root Beer Extract stayed in the public's mind. If people couldn't drink beer, why not go for a root beer? Suddenly stands like Allen's were jam-packed. This beverage was supposed to be the next best thing.

[Featured image by Boston Public Library via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-2.0]

Your root beer came in an icy mug

Root beer is an all-American drink — its defining flavors have a long history. Native Americans made hot medicinal teas with sarsaparilla and added sassafras to soup to thicken and add flavor. Colonists from Europe, on the other hand, had a tradition of brewing plants into alcoholic beverages, so they took sassafras and sarsaparilla and made small beer, which has a shorter fermentation period and smaller batch sizes. When Charles Hires first marketed his packets of flavorful powder for a drink, he called it root tea. When mixed with water, sugar, and yeast and allowed to ferment, it became a carbonated — and non-alcoholic — drink. Only later did he change the name to root beer as a way to appeal to Pennsylvania coal miners.

Americans sipped warm root beer for decades, and it's surprising anyone liked it enough this way to continue drinking it, but they did. Then, Roy Allen popularized serving it cold at his Lodi, Stockton, and Sacramento root beer stands. The first electric refrigerator for home use had come onto the market in 1913 and was one of the secrets to Allen's success. He even developed a special cooling system along with his business partner, Frank Wright, to ensure that the stands' root beer was always deliciously chilly. The root beer purveyor had the clarity to serve the beverage icy cold in glass mugs. He changed the public's perception of the best way to consume it.

You couldn't order a root beer float

Every year on August 6, A&W celebrates Root Beer Float Day and sometimes even gives away free floats. This menu item is so much a part the chain's identity today that it's impossible to imagine going to A&W and ordering anything else. Yet, there were no floats on the menu at the first root beer stands.

People have been adding ice cream to root beer since at least the 1870s. There's evidence that Robert M. Green combined the soda from the store where he worked with ice cream from the 1876 Philadelphia World's Fair and created the concoction. Even though this ice cream treat predates Allen's root beer stand by nearly 40 years, root beer floats weren't featured on A&W's menu until decades later, perhaps because of the necessary infrastructure for making, keeping, and serving ice cream. Some A&W locations could have served floats early on while others didn't — the chain's menus showed a huge variation from franchise to franchise. As late as the 1960s, there were still A&W menus without floats. For example, a vintage menu on the chain's Facebook account lists root beer for $0.10 and offers a sundae for $0.30, but there is a glaring lack of a root beer float.

A&W's root beer was foamier

A mug of root beer in 1920 at an A&W stand probably had foam dripping off the top of it — more than it does now — and the soda also must have tasted different than what it does today. That's because several elements of the manufacturing process have changed.

First, the amount of foam in root beer was linked to the use of sassafras. This ingredient, traditionally employed as a thickener by Native Americans, also has a distinct flavor and creaminess to it. A&W and other root beer brewers had to stop using sassafras in 1960, though, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration banned it after it was found to be carcinogenic. Now, companies use artificial flavorings to mimic the taste and texture of the traditional plant. That's probably good for health reasons, but it leaves today's root beer drinkers wondering what they're missing out on.

In the beginning, A&W founder Roy Allen was hand-brewing the beverage in small batches. That gave him precise control over the ingredients and procedures he used, but it also meant that one batch of root beer might differ somewhat from another. Today, the industrial process involved in making more than 1.1 million gallons of root beer each year for the chain of restaurants means every glass of A&W root beer tastes the same as another whether you're in California or Michigan and whether you drink it in June or December.

You could go to A&W year-round

"Car hops in the snow," read a 2020 Forbes headline about one of the busiest A&Ws in the country, located in southern Michigan. Wisconsin, where winters are equally snowy, has the second highest number of A&W restaurants in the U.S., coming in after the chain's home state of California. Michigan takes third place. The Michigan restaurant's opening hours were newsworthy because this drive-in restaurant had only ever been a seasonal business in previous years. Now, it would stay open through the blisteringly cold months of January and February. The car hops would be wearing ski clothes to carry trays to parked cars.

Root beer is, and has traditionally been, a seasonal treat in many parts of the country like Michigan and Wisconsin. In areas with chilly winters, hot chocolate just sounds more tempting than an icy mug of root beer when the temperature dips below freezing. So, you may think of A&W as a seasonal restaurant if you live in that region, but the first locations probably stayed open year round, just like A&W's locations with indoor seating.

In Lodi, Stockton, and Sacramento, cold weather wasn't much of an issue for Roy Allen. It rarely freezes in Lodi. A&W's first root beer stands could stay open all year, and people would still consume the chilled beverage. Being able to sell this product in cold weather only became an issue once franchisees took the beverage to the Midwest and East Coast.

Your kids got free drinks

If you ask a baby boomer about A&W root beer, they'll get a wistful look in their eyes and say, "They had these little mugs when I was a kid." The company officially calls those tiny glasses baby mugs, and they stem from a tradition started by A&W founder Roy Allen as early as 1921. He lured parents and families to his root beer stand by advertising that kids could drink for free. At the time, tiny disposable paper cups weren't widely available, though. Restaurants served drinks in glass mugs, but the root beer mugs at A&W were too heavy for littles to hold easily. That led Allen to order baby mugs from the Indiana Glass Company. The earliest version of these mugs held 3.5 ounces of root beer.

The mugs are beloved by the generations of people who remember drinking from them. So, today, A&W sells a commemorative set of two, featuring the chain's Rooty mascot, for about $11, but at today's restaurants kids no longer drink free.

[Featured image by Kiddo27 via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC-BY-SA-4.0]

You might have eaten a tamale with your root beer

A&W franchisee Dale Mulder of Lansing, Michigan, invented the bacon cheeseburger in 1963. After that, the root beer chain add this item to the menus of its locations across the country and, in the years to come, it changed the landscape of fast food offerings worldwide. Forty years earlier, though, you wouldn't have even found a plain hamburger at an A&W stand. Roy Allen didn't even offer food on the original menu, and the chain only started selling snacks in the 1930s during the Great Depression to increase earnings. Even so, edibles weren't an important part of the chain's profits until the 1950s.

Bill and Alice Marriott — whose family's business later grew into a hotel chain — were some of Allen's initial investors. The young couple were also among the first franchisees to sell food along with A&W root beer in 1927. They had taken Allen's brand of drink to the East Coast but discovered that cold root beer on its own didn't sell well in chilly Washington, D.C., winters. To make more money in the off season, they added finger foods to the menu at their newly named Hot Shoppe. Some workers from the Mexican Embassy just down the street shared a fantastic recipe for tamales, and this became a staple on the menu alongside hot dogs and barbecue sandwiches.