What You Need To Know About Grocery Store Bar Codes

Barcodes have made purchasing and product tracking a lot easier and faster than they used to be, especially for grocery stores. A barcode may at first seem like a simple concept, but the reality is that these simple lines are the result of decades of research by major corporations and scientific labs. Together, grocers and scientists have harnessed the power of microchips and lasers to create a way for you to buy boxed mac and cheese more efficiently.

Jokes aside, the barcode really did revolutionize the grocery and retail industries, but it hasn't always proven to be a perfect tool. In fact, the barcode you know is almost certainly going to change in just a few years to keep up with consumers' increasing desire to know more about the products they buy. It's just one transformation in a series of many that's helped to make the process of stocking shelves and shopping a smoother experience for grocers and consumers alike. Here's what you need to know about grocery store barcodes.

Researchers first developed codes at the request of grocers

The idea for a way to speed up the grocery checkout process came courtesy of a supermarket manager in Philadelphia. At his store, it was taking simply too long for customers to get through the checkout line. Simultaneously, inventory was a time-consuming process. Searching for a solution, the manager asked a dean at the Drexel Institute of Technology if they could figure out a way to make those processes go faster, as well as making them more cost-efficient. At that point, grocery employees had to enter product prices into the register by hand. While experienced cashiers could do this quickly, it presented a bit of a learning curve for newer employees and just wasn't that fast overall.

Drexel graduate student Bernard Silver heard about the request and, together with Drexel alumnus and inventor Norman Joseph Woodland, began to think about what could be done to address the issue. Woodland was the first to come up with a barcode-like idea in early 1949, which he and Silver patented in 1952.

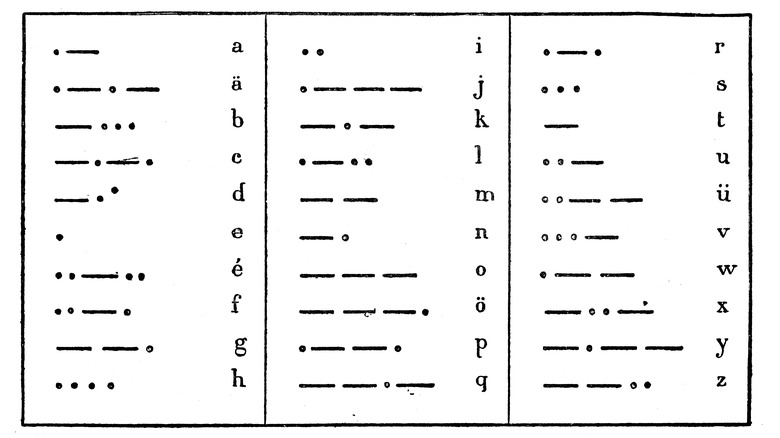

The idea for a barcode was based on Morse code

Woodland got his idea for the barcode in the most idyllic of ways: while sitting on a beach in Florida and pleasantly reminiscing about the Morse code he'd learned during his time in the Boy Scouts. While there, Woodland put his fingers into the sand and pulled them back, mentally connecting the lines of different widths to the dots and dashes that make up the basis of Morse code.

He figured there could be some way to use a similar system of thick and thin lines as a sort of Morse code for grocery identification, just as the dots and dashes represented letters and could be combined to convey information. But he was very aware that Morse code needed to run in a specific direction so it could make sense to interpreters, so he changed the straight lines to concentric circles. It would be a few decades before the rectangular barcode model rose to prominence.

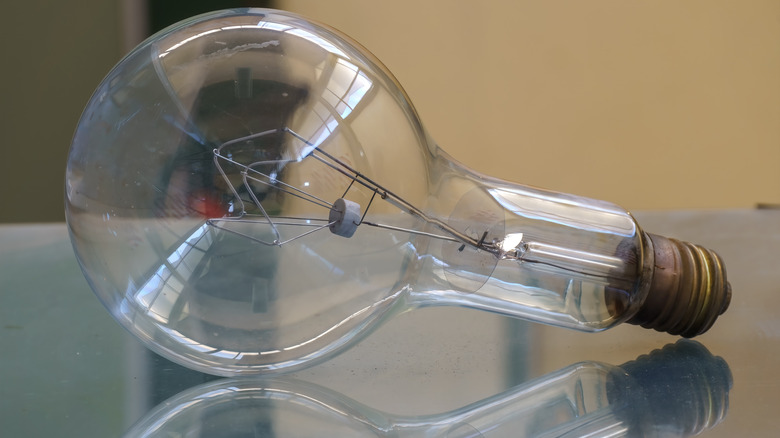

Barcode use was thwarted for years because it needed large and expensive equipment

After Woodland and Silver came up with the idea for a code that could make grocery shopping more efficient, they tried to build a machine that could actually read it. They came up with something that could sort of decipher the code, but it required a 500-watt light bulb and a machine that was the size of a desk. That wasn't exactly the efficient and speedy machine that grocers had begged for. Meanwhile, the setup needed to print and use the barcodes was just too expensive. Even worse, the incandescent light was so bright that test papers kept catching on fire.

It wasn't until the creation of the laser in the 1960s that good scanning technology that wouldn't immediately start fires became available and a final barcode format was created. Even then, it took quite a bit of trial and error to create equipment that not only worked, but could be used in supermarkets and grocery stores across the country.

The barcode was originally designed as a bullseye

Being able to scan a price from any direction was a central goal in the barcode-crafting process. If a cashier had to turn everything to face a certain way when they were trying to scan barcodes, any time savings created by the scanner would be eaten up by the time needed to orient products correctly. To keep things efficient, the code had to be readable no matter how the cashier scanned it. That way, the cashier could keep products moving past the register.

When Woodland first came up with the idea for a barcode, he designed it as a bullseye. The round design would allow scanners to read the entire code from any direction. Woodland and Silver even went so far as to have the round design patented. They eventually sold the patent, which was sold again to the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), which was known for electronics, music, and radio ventures.

When researchers at RCA decided to work on grocery scanning technology in the 1960s, their in-store test stickers used the bullseye design. But the circular design required complicated printing equipment and didn't leave a lot of room for errors. Then, IBM got involved. Woodland was working for IBM then, but a man named George Laurer actually gave the design a shot, ultimately creating a rectangular barcode that could be read by a laser.

Barcodes weren't widely used until 1974

The first inkling of what was to become a barcode was that series of lines drawn in the sand in 1949, but barcodes as we know them weren't actually used outside of testing until the middle of the 1970s. Due to technological barriers, barcode scanning technology just didn't work that well or had other practical issues that prevented its use. Rail companies did devise a series of light-read stripes that could identify rail cars, but these stripes were huge and obviously wouldn't have worked on your average can of corn.

By the early 1970s, barcode research had progressed enough so that RCA was ready to test its working model of a circular bullseye code. RCA chose a Kroger store in Cincinnati for an 18-month test that proved to be mostly successful. However, that test also showed that the bullseye codes, which were printed on stickers that were applied to products, smeared easily and quickly became unreadable.

The grocery store barcode is known as a universal product code

All grocery store barcodes are barcodes, but not all barcodes are grocery store barcodes. In other words, there are different types of barcodes, with the most common type currently used for grocery and retail products. This is known as the universal product code, or UPC. It's considered to be universal because all retailers should be able to read the same codes with the same basic equipment. Or at least, that was meant to be the case in the U.S. Outside of the United States, products may have a European Article Number, or EAN. This is also a barcode, just with a different numerical format.

In the same vein, you may have heard people talk about SKU numbers (typically pronounced as "skew") when referring to barcodes on products. SKU stands for stock-keeping unit and is an internal code created by the manufacturer to identify products. Formats for SKUs can vary, may incude letters, and may or may not have a barcode. Meanwhile, UPCs are always 12 digits that are broken up into groups of 1-5-5-1 and printed beneath a barcode. And unlike UPCs, SKUs are not usable by other manufacturers or stores.

Adoption of bar codes wasn't immediate

Despite the fact that grocers were practically begging for ways to make the checkout and inventory process faster, the barcode wasn't adopted immediately. For grocers, the cost of installing scanning equipment, even in its newest form in the 1970s, was a major expenditure. Moreover, many didn't want to add the equipment until manufacturers put barcodes on their products. Meanwhile, manufacturers were reluctant to add barcodes to products, as that meant they would have to adjust packaging graphics en masse, and they saw no sense in doing that as long as grocers didn't have barcode scanners. Clearly, the industry was caught in a catch-22.

Even more resistance came from consumer advocates because part of the transition to using barcode scanners involved removing the price tags from products. At this point, aach product in a store had a price tag that cost stores money to apply. That's because those stores had to pay employees to manually add the tags, and the thinking was that stores wouldn't have to tag each and every item if the barcodes worked. But that wasn't a popular idea with consumer advocates and state governments, which passed laws requiring the old style of pricing to continue. However, barcodes proved to be too useful to ignore, and they eventually made their way into stores everywhere despite the initial stumbles.

New barcode scanner technology was behind an infamous presidential tale

In early 1992, then-President George H.W. Bush visited a grocer's convention in Florida. He was at one exhibit on grocery scanning technology and, according to legend, was mesmerized by the scanner and basic checkout technology. This got spun into an embarrassing critique of the president in which he was presented as hilariously clueless about how regular, grocery shopping Americans lived their lives. After all, it was a grocery checkout scanner, something not worth marveling over in the early 1990s.

But that's not what really happened. Yes, Bush was amazed at the technology, but the tech in question was not your typical checkout scanner at the time. Instead, Bush had been looking at an experimental scanner that could read severely damaged barcodes and a checkout scale for weighing produce, neither of which were in grocery stores at that point.

Even worse, the reporter who first ridiculed Bush hadn't even been at the convention to see the president's reaction and, according to Snopes, was writing a story based off a short report that had little detail. The Associated Press tried to set the story straight, but the myth of a clueless Bush not understanding how a grocery store worked persisted for years. The tall tale even found its way into an obituary published after Bush died.

The white space on either side of a barcode is necessary

Take a look at a barcode on a label that doesn't have a white background, and you'll see that the black and white lines are usually surrounded by a white space that's been carved out of the graphics. Look even more closely, and you'll notice that the sides of the code have more space than on top or below. These strips of white space are commonly called the quiet zone. This is meant as a buffer between the code and the graphics on the product's packaging.

Simple as they may seem, these white spaces are necessary. If the barcode lines were placed among the other graphics on a package, the scanner could misread the code, either taking some of the graphics to be part of the code or not reading the code at all. The quiet space also has to be a certain size to ensure that the scanner can read the code from either direction.

UPCs technically can appear in different color combinations, but many of these are hard for scanners to read accurately. Light bars on a light background and dark bars on a dark background are generally unreadable. A white background with black bars is the most readable combination, which is why it's the look you're most likely to find on products throughout the grocery store.

Consumers can't get much information from a UPC

If you know how to break down the numbers on a UPC barcode, then you, as a consumer, still can't do much with the information. That's because these codes don't help on the purchase side that much, other than allowing you to match a product to a price label on a disorganized shelf. Instead, UPC codes are meant to help grocers and retailers through the supply chain and in the store, not the consumer as they buy and use the product. Even so-called scanning apps don't do much except to log the product on, say, a shopping list on your phone.

UPCs can easily be matched to basic information in these apps, such as an image of the product or its nutrition label; for comparison, think of the barcode scanners you might find inside calorie-tracking apps that autofill macronutrient counts. But for detailed information, like where your bagged produce was grown or the journey your food has been on from field to store, you will still be left searching the packaging for information.

Barcodes will possibly be replaced by 2027

Now that you've learned all about UPCs, guess what? They're likely going away. GS1, the organization that issues the numbers, has a program known as Sunrise 2027, which is supposed to replace the familiar vertical-line barcode on food products with what as been deemed a 2D barcode that looks like a QR code. Instead of containing the usual numbers and bars, the 2D codes contain a URL that includes the UPC number.

The transition to a QR-style code has direct effects for consumers. Just as you can use an app on your phone to scan a QR code in an ad or an email, you'll supposedly be able to scan these 2D barcodes to receive information about the product that goes beyond what's already on the product's label.

As an illustration, you can think of the UPC barcode as a simple license plate, while the more complex 2D code would allow manufacturers to provide more detailed information about a specific product. This can include relevant info such as supply chain information, product registration, and storage and cooking instructions, all contained within that one code. Theoretically, the 2D code would also mean that you no longer would have to search a price sign for codes about discounts and discontinuation. Combined with retailer-driven changes such as image recognition, RFIDs, and the Just Walk Out technology created for Amazon Go, the checkout experience is likely going to change dramatically for consumers over the next few years.

UPCs used to be reusable

Manufacturers and suppliers pay for each UPC. They can also buy or lease the numbers, paying a fee up front and a renewal fee each year. Of course, that can get expensive. For years, manufacturers were able to reuse UPCs as long as the discontinued product had been out of service for a certain number of months, which could vary according to the product category.

Then, in 2017, GS1 announced that, starting on January 1, 2019, companies could no longer reuse UPCs (also known as Global Trade Item Numbers or GTINs) from a discontinued product. The change followed a period of increasing concern over the misuse of reused GTINs. Companies weren't waiting the required number of months between the discontinuation of the original product and the introduction of the new product, which often resulted in a barcode that rang up as the wrong product.

A 2016 survey conducted by the Retail Value Chain Federation found that retailer and supplier computer systems often had mismatched records as a result of hasty UPC reusal. Old GTIN records haunted retailer systems and caused delays as companies tried to delete them to allow the new GTIN assignment to show up properly. Retailers and suppliers also had to hunt down items with the GTIN to ensure the original items were no longer available.

UPCs can be blocked when products are recalled

You may think of a barcode as something that just lets you ring up food quickly, but it's also a very handy tool in case of a recall. When you, as a customer, hear about products that have been recalled, you're usually told to check lot numbers and best-by dates of items you have already bought to see if you already have any of the affected products at home. You also likely trust that store staff have pulled all of the products with affected lot numbers and dates off the shelf.

However, a store's response to a recall can get more intense than that. Workers do remove items from shelves and search in the back stockroom to find any extras that might be lurking there. However, they know to look for the products in the first place because their main company's central office has hopefully been tracking the product's UPC numbers and determined that their store received those specific lot numbers or dates. The company can even go so far as to block the barcode, meaning it won't scan at all at the register, although a cashier could override the block.