Unmasking Chef David Ruggerio's Mafia Past

When fame hits, celebrity chefs assume a responsibility to be more open, to let us get to know who they are, where they come from, and why they love to cook. For Chef David Ruggerio, these personal details were bound by a code of silence. If broken, the consequences could be fatal. Ruggerio is a New York City native who spent the '80s and '90s learning the art of French haute cuisine, breathing new life into some of Manhattan's most well-known fine dining restaurants, and fronting his own TV shows on PBS and Food Network. Grievous business errors toppled Chef Ruggerio from his status as a high-profile celebrity chef and plunged him into utter obscurity in what seemed like the blink of an eye.

With his professional reputation permanently sullied, Ruggerio passed the years that followed struggling to grip a middle rung on the ladder of success, but in 2022, a bombshell public confession would thrust Ruggerio back into the public eye. In great detail, Ruggerio described what his life was really like while at the height of his success — as a made-man in New York City's Italian Mob. The contents of his dark tale unspool like a Mario Puzo novel, describing a man's tawdry tango with power, corruption, and ruthlessness. Ruggerio's brushes with culinary brilliance, nor his charismatic media persona, were enough to surmount his blood ties to the ruthless world of organized crime. This is the unmasking of Chef David Ruggerio's Mafia past.

David Ruggerio isn't his original name

New Yorkers inhabiting the city in the mid- to late-20th century or anyone with a little Mafia history under their belt are probably familiar with the Gambino name. For the better part of the 1900s, the Gambinos were one of New York City's infamous "Five Families" — an intricate, well-established criminal organization at the heart of the Italian Mafia's enterprises. Chef Ruggerio was born into this world on June 26, 1962. His name at birth was Sabatino Antonino Gambino, son of Saverio Erasmo Gambino, a Sicilian-born Mafia. Saverio Gambino was first cousins with Carlo Gambino, a notorious mobster who served as head of The Commission — the highest position possible in the Mob – from 1957 until his death in 1976. With a family tree this conspicuous, Ruggerio may have had a tougher time making a name for himself as a celebrity chef if he hadn't already changed his own.

The name "David Ruggerio" didn't come out of thin air, but it was still somewhat random. As a young child, Ruggerio was adopted by his mother's new husband under the condition that he and his sister's names were changed. His mother called them David and Lisa after the title characters in her favorite film and "Ruggerio" came from a respelling of his grandmother's maiden name.

His childhood was plagued by tragedy and violence

David Ruggerio did not know his father during his formative years. He was deported to Sicily and jailed for trafficking heroin, leaving Ruggerio in the care of his mother and an abusive stepfather. Between the ages of 4 and 5, Ruggerio experienced the loss of his infant sister and witnessed his mother die of an asthma attack. Afterward, he was sent to live with his grandparents in East Flatbush, a Brooklyn neighborhood that by the 1960s was plagued by murder and other violent crimes.

Ruggerio cites his early experiences with death as hardening his emotions. It wasn't long before Ruggerio fell in with his father's Mafia associates who influenced and facilitated the youngster's earliest dabbling in illegal activity, which included card game schemes and selling stolen goods. In an interview on "The Douglas Coleman Show" Ruggerio said, "By the time I was 10 I was arrested six times." At 11, Ruggerio stood by as his mentor Egidio "Ernie Boy" Onorato murdered F.B.I. informant Anthony Finn in a Manhattan alley before helping Onorato move the corpse into a car. When speaking about his childhood to Vanity Fair, Ruggerio reflected, "Did I want to be a gangster? Never one day did I say to myself, 'Yeah, I want to be a gangster when I grow up.'" He continued, "All I wanted to do was survive the next day."

By the age of 14, Ruggerio was a made man in the Mob

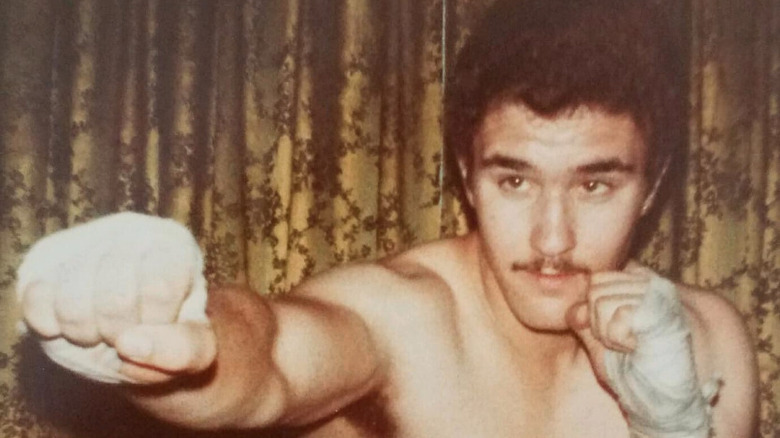

Although much of Ruggerio's youth was spent being primed to rise through the ranks in the Gambino crime family, some positive aspects of his adolescence included spending time with his grandmother in the kitchen and training under Brooklyn boxing legend Izzy Zerling. But when Ruggerio's father was released from jail and resurfaced in Brooklyn, he wasted no time schooling his son in the ways of heroin trafficking and loansharking.

In 1977, Ruggerio's father brought him to Sicily where he became "made." This official induction into La Cosa Nostra took place in the basement of a village café, during which Ruggerio was tattooed on his right shoulder with a dirty needle — the burning cross and the words "Uomo de Fiducia," or "Man of Trust," a permanent reminder of the family he was born into and the life he felt destined to lead. During high school, Ruggerio became a drug dealer for the Mob, raking in thousands of dollars and taking trips to his mentor Onorato's home in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, where cocaine-fueled sex parties were the norm. It hardly mattered when Ruggerio was expelled from school — as a made man, life in the Mafia seemed like the only education he would need.

A foiled murder plot led to Ruggerio becoming a chef

By the early 1980s, life was only getting tougher for Ruggerio. By then, he had watched Onorato savagely murder people over the slightest perceptions of disloyalty. Ruggerio also believed that Onorato was behind the deaths of his best friend and his girlfriend. To even the score, Ruggerio hatched a plot to kidnap his former mentor and murder him inside a stolen ice cream truck. The Gambino family was aware that tensions between Ruggerio and Onorato had reached a boiling point, and Ruggerio was reassigned to work for Gambino lieutenant Carmine Lombardozzi. Unlike Onorato, whose specialties were murder and mayhem, Lombardozzi took a more meticulous "hide in plain sight" approach to organized crime. For one, he required his crew to work in legitimate professions.

Inspired by the years he spent with his grandmother in the kitchen, Ruggerio set out to become a chef. He knew well enough that the most respected New York City chefs worked in Manhattan and were experts in French cuisine. Armed with stacks of Gourmet magazines and classic French cookbooks, Ruggerio educated himself on the basics. He knew where to go and what he had to do — or so he thought.

Ruggerio received a crash course in French cooking at Manhattan restaurant La Caravelle

From his research, Ruggerio knew that the two best French restaurants in Manhattan were Lutèce and La Caravelle. The lack of job openings at Lutèce steered Ruggerio toward La Caravelle. He had to ask for a job in the kitchen 13 times before finally being given a position making vegetables and soups. On "The Douglas Coleman Show" Ruggerio described the initial experience as "baptism by fire" adding, " ... from the streets of Brooklyn, you couldn't deter me."

The street survival tactics that had toughened Ruggerio from a tender age were also what threatened to destroy his chance of succeeding in the fine-dining world. A late-night subway brawl involving a mugger led to Ruggerio spending a week in jail on an attempted murder charge. Out on bail and desperate to keep his job at La Caravelle, Ruggerio approached head chef Roger Fessaguet with tears in his eyes, pleading to be sent to France to train with the elite chefs there. Fessaguet agreed and made arrangements for Ruggerio to make something of himself in Nice under the condition that he return to work at La Caravelle when he was done.

His training in France was a brief escape from a life of crime

When Ruggerio arrived in Nice, His first apprenticeship was under Chef Jacques Maximin, better known in the French media as "Bonaparte of the Ovens." For the next year, Ruggerio learned from some of the most renowned chefs who were working in the South of France in the early '80s, including Maximin's mentor Roger Vergé and Alain Ducasse. Back in Brooklyn, Ruggerio's Mafia associates were busy persuading the man who fought with Ruggerio in the subway to stop cooperating with law enforcement regarding the case.

Before heading home, Ruggerio made his way toward Lyon, where he culminated this once in a lifetime opportunity by working under Chef Georges Blanc and Chef Michel Guérard, described by Ruggerio on "The Douglas Coleman Show" as "to me, and to most people ... the greatest chef of the 20th century." Though his time in France would be monumental in helping Ruggerio elevate his culinary career – he became the executive chef at La Caravelle in his mid-20s — his return to New York signaled the resuming of his treacherous double life.

Ruggerio's culinary status may have kept John Gotti from murdering him

In the mid-1980s, the hierarchy of the Gambino crime family was shaken up in a dramatic way. After Carlo Gambino died in 1976, Paul Castellano took over as the head of the family and the leader of The Commission. Castellano was facing a series of federal racketeering charges in 1985 when he and his bodyguard were gunned down in front of Manhattan's Sparks Steak House on the night of December 16th that same year. The massacre was orchestrated by none other than John Gotti, who sought to eliminate Castellano and take his place as the Gambino family don.

Gotti's swift rise to power wasn't exactly a welcome invitation in Ruggerio's eyes. Ruggerio was aligned with Gambino associates like Danny Marino whose loyalty to Paul Castellano was in immediate conflict with Gotti's ill-gotten promotion. At first, Ruggerio avoided Gotti as much as possible, but his prominence as a chef actually attracted positive attention from the Teflon Don. Ruggerio was hired at French fashion designer Pierre Cardin's restaurant Maxim's in 1990 — an establishment Gotti happened to be a big fan of. Months after taking the position, Gotti held his 50th birthday celebration at Maxim's. For the occasion, Ruggerio snuffed out FBI surveillance by papering Maxim's windows and cooked an opulent meal. Shortly after, Gotti was sentenced to life in prison, where he died of throat cancer in 2002 at the age of 61.

Ruggerio acquired ownership of a high-end restaurant through a Mafioso scheme

After his time at the helm of Maxim's, other old-school owners of outdated French restaurants in midtown Manhattan wanted Ruggerio. He took the job at Le Chantilly through a business relationship he formed with Camille Dulac, who wanted to revamp the tired mid-century French menu. Ruggerio was interested, but after he took the job, he found out that Dulac concealed the fact that Le Chantilly was in serious debt and on the verge of liquidation via auction.

With one foot already in the door, a furious Ruggerio vouched for Dulac so that his Mafia connections could bail him out yet again. Ruggerio recognized the auctioneer overseeing the liquidation of Le Chantilly as a low-ranking mobster. Backed by the Gambino family's money, he conspired with the auctioneer to fix the auction and become owner. Just as this was happening, The New York Times was publishing rave three-star reviews about Le Chantilly. If there was a time Ruggerio felt untouchable, this was it.

He allegedly abducted his business partner after a financial dispute

Despite good reviews, Ruggerio continued to have financial troubles at Le Chantilly. Ruggerio claims that Dulac also forgot to mention that Le Chantilly was wanted by the taxman for a significant sum of money. From a culinary standpoint, Ruggerio was at the top of his game, but his crooked business dealings were getting harder to conceal.

Unable to hide his contempt, Ruggerio once punched Dulac in the face in front of Le Chantilly in broad daylight. He threatened Dulac, saying that if he didn't surrender his share of their mutual business ventures, he would be killed. But things would only escalate from there. As is the Gambino way, Ruggerio and his associates trailed Dulac in a van and pulled him inside. They drove him to a beach in Queens and dangled him over a pre-dug open grave and forced him to sign a severance contract. According to Vanity Fair, Dulac maintains that this never happened.

Despite the drama, TV networks came calling

Ruggerio's falling out with Dulac occurred in 1995 but his less-than-modest approach to conflict didn't dim Ruggerio's rising star. With media outlets like Food Network gaining serious popularity in the '90s, it was hardly a surprise when television reps got in touch with Ruggerio. An endearing presence on vintage clips of shows he hosted like PBS' "Little Italy" and Food Network's "Ruggerio to Go," his thick Brooklyn accent, gold jewelry, and passion for celebrating the culinary greats of his home city remind us why shows like "Anthony Bourdain: No Reservations" and "Parts Unknown" were such successes years later.

"Ruggerio To Go" only ran for one season in 1998 and 1999, but segments on talk shows were also the norm in those days. On screen, Ruggerio portrayed himself as just a regular guy from the neighborhood, just as he had done during the years he trained under and worked with legendary French chefs. Looking at the footage of "Little Italy" and "Ruggerio to Go" now, one might wonder if some of the people who appeared with him on TV — such as the local owners and managers of New York City institutions like Katz's Deli and Totonno's – knew what Ruggerio was really involved in.

Like many mobsters, Ruggerio's downfall was greed

Perhaps juggling ownership of some of NYC's poshest restaurants, working in television, and having a secret life in the Mob was too much for Ruggerio. In the summer of 1998, the police raided Le Chantilly on suspicion of fraud. Ruggerio was the center of accusations that the restaurant was embroiled in a credit card scheme that involved massively inflating credit card tips in numbers that stretched to the hundreds of thousands. According to a November 1998 article in the New York Times, one instance charged Ruggerio with adding a $30,000 tip to a $1,000 dinner bill.

Ruggerio was arrested and ultimately pleaded guilty to attempted grand larceny. The damage to his reputation cut deep. Years of cultivating respect in the Mafia were all but gone while reports in the media openly questioned the integrity of his character. The same New York Times article that wrote of the credit card scandal at Le Chantilly also said of Ruggerio, " ... instead of submerging his Brooklyn roots, he would go on to market himself with a Barnumesque sense of self-promotion — a celebrity chef who peppered his cooking tips with hefty pinches of New York street smarts."

From culinary A-lister to ... strip club co-owner?

After Le Chantilly closed in 1999, Ruggerio's media appearances became very scarce. In 2002, he opened Rouge — a French fusion-type restaurant in Manhattan that was featured on the culinary show "Carmine's Table" but earned a rough one-star review from The New York Times. Rouge ended up closing and prompting a period of professional instability for Ruggerio. A turn as co-owner at Lansky's Deli circa 2008 didn't fare well and a fleeting stint at the chain Sushi a Go-Go was a far cry from his haute cuisine days. Ruggerio also owned a donut shop for a few years, around the same time he co-owned a strip club.

Reflecting on his tribulations to Vanity Fair, Ruggerio said, "After the credit cards, the press just categorized me as a moron because I f***ed up my TV career. I had five restaurants, 650 employees. And it was gone," Yet the sobering reality of his once illustrious culinary career being over didn't snap Ruggerio out of the habit of running scams. In 2014, he was arrested for forging a check. In order to avoid jail time, Ruggerio pleaded guilty.

The untimely death of his son caused Ruggerio to come clean

June 21, 2014, is a day that Ruggerio will never get out of his mind. That morning he received a call that his first-born son Anthony had died at the age of 27 — likely of a drug and alcohol overdose. In an August 2014 Facebook post, Ruggerio wrote, "I have experienced grief my whole life, but nothing like losing my son Anthony." When one of Ruggerio's longtime Gambino associates failed to attend Anthony's funeral, Ruggerio decided to turn his back on Mafia life for good, but he wouldn't go quietly.

It's easy to see from Ruggerio's TV days that he's a natural-born storyteller, but after a lifetime of secrecy and deception, he is finally telling his truth. Ruggerio burst the details of his past wide open in an exposé with Vanity Fair magazine published in March 2022. He continues to regularly post memorial tributes to his son. In recent years, Ruggerio has " ... traded in my knife for a pen" as he wrote on his website, and has written several novels. He has also been at work on his memoirs, in which he included the line, "Everything within these pages is accurate ... There was no need to embellish; the truths were horrific enough."

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).