Unique Foods People Used To Eat For Christmas

For many of us — especially if you're a citizen of the western world — Christmas dinner usually means a large feast of turkey or ham, served with potatoes, vegetable casseroles, and all the other usual trappings of that classic festive meal. Look further abroad, however, and you'll find a few more curious traditions. In Puerto Rico they drink their own version of spiked eggnog from coconut shells. The traditional Christmas meal in Japan is KFC.

What you'll find overseas, though, is nothing compared to the kinds of things they used to eat in the past. The same festive traditions that might have seemed humdrum to them would elicit a fair bit of surprise nowadays — unless you're used to serving sheep's heads, puddings made of real snow, and gravy made of fruit on or around the big day. If not, take a gander and see if any of these old school recipes appeal. They might just come in useful once you finally tire of the turkey.

Roasted peacock

Bird of some kind is one of the mainstays of the Christmas dinner, and has been for centuries. While we peasants may be more used to things like turkey, chicken or other such things, the royals of the medieval period had a much fancier bird in mind when it came to their yuletide feasts.

In 1938, Richard II held a sumptuous Christmas party at the newly remodelled Westminster Hall in London. The guests, including attendants, pages, clerks and servants, numbered somewhere around 10,000 people during the 12 days of Christmas. Unsurprisingly, Richard went in as hard on the menu as he did the guest list. After a number of other courses, including pies, sweetmeats (we'll come onto those later) and glazed boars' heads, visitors to Westminster Hall were served a dish of roasted peacock, dressed in its own feathers (which were seat aside before roasting) so as to give the illusion that the bird was still alive — a popular presentation with many wealthy Europeans. A specially-chosen knight then took the "peacock vow," a promise to perform some spectacular feat of heroism in the future, before carving the bird up.

Smalahove

The Scandinavians aren't exactly afraid of serving up a couple of — shall we say — questionable dishes every now and again, and this is perhaps illustrated nowhere better than with smalahove. Also known as smalehovud or skjelte, this Norwegian Christmas dish takes it name from "smale," a word for "sheep," and "hovud," meaning "head." You can probably guess what it is.

In days gone by, smalahove was eaten by the poor during the Christmas season, and as a way of making the most of the sheep they ate — though nowadays it's a delicacy. It's made by torching the skin of the sheep, removing its brain, and then salting (or smoking) the head. That head is then boiled or steamed for three hours and served with a side of sausage, mashed rutabaga and potatoes. Nowadays, it's traditionally served with aquavit, a type of vodka which Bon Appetit describe as "emphatically not" subtle. According to Relocation.no, the best parts of smalahove include the ear, the eye and the tongue. If that's not enough, of course, some Norwegians choose to eat it with the brains still inside. And you thought Brussels sprouts were bad.

Sweetmeats

The festive sweetmeat tradition is another quirk that found popularity in medieval, Tudor, and Elizabethan England. As it is today, Christmas was a big deal back then and provided wealthy households and families the chance to show off their own wealth and social status. The sweetmeat course of the feast was a vital part of this display. (And just a reminder, sweetmeats were not meat, but actual sweets. It's the sweetbreads that were made of meat.)

Although sweetmeats in the medieval period mostly included things like marzipan and pastry, the Elizabethans had a easier access to a certain special (and highly expensive) ingredient, with which to make the course even more spectacular: sugar. Sweetmeats from this time include collops of bacon, which were made from ground almonds and sugar; sugar-plate, a type of gelatin which could be molded into various shapes; and leech, which was a milk-based confection made from sugar and rosewater. These foods were arranged in jaw-dropping, colorful displays, many of which included fruit, gold leaf and gingerbread as trappings, with an aim to impressing the host's guests as much as feasibly possible.

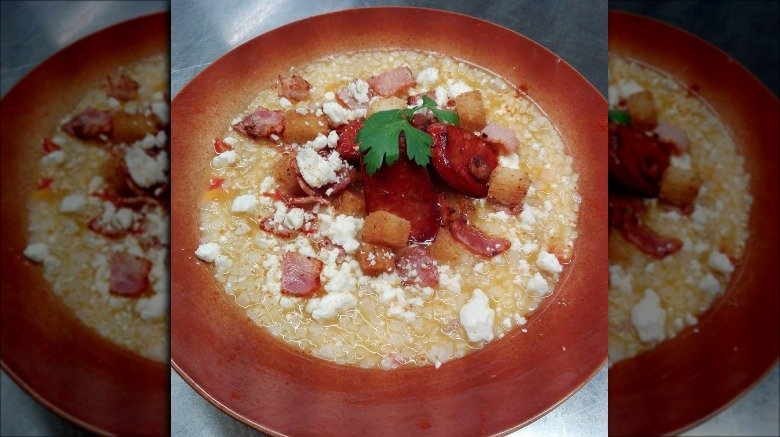

Frumenty

While the medieval nobility and royalty were up in their fancy halls eating marzipan, peacock, and boars' heads, the ordinary folk were huddling around a far less appetizing meal for their Christmas dinners. Frumenty finds its origins as far back as the 14th century, with a reference to the recipe in a 1390 cookbook. There are actually two versions of the dish: one which is supposed to be fit for the common home and another, made with porpoise, which was made for the higher classes.

Put short, the plain version of frumenty is a dish made from cracked wheat cooked in almond milk. It's not entirely dissimilar to porridge, and was a staple food in the everyday diets of many medieval people. For the people of Yorkshire at least, it was a crucial part of the Christmas meal, and it's likely this tradition extended elsewhere around the country — especially among the poorer parts of society, who saved it for use on special occasions.

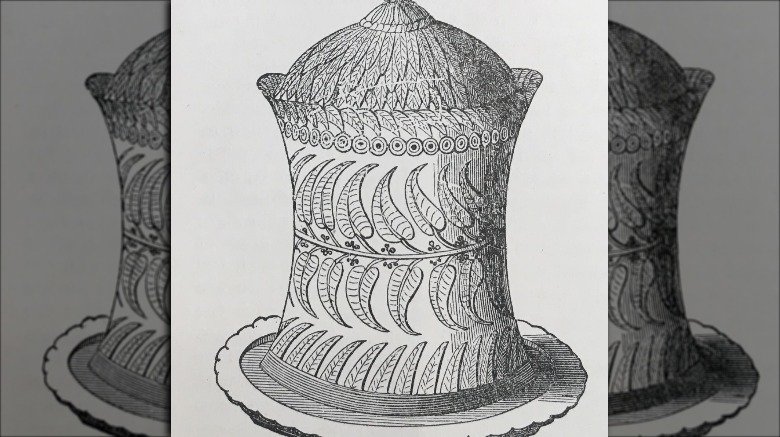

The Yorkshire Pie

Never say the Victorians couldn't do ridiculous opulence. Despite having garnered something of a reputation for straight-faced humility, the upper classes during this period weren't afraid of a little bit of excess. That much becomes pretty clear the moment you first gaze upon the recipe for the Yorkshire Pie.

It consists of an eye-watering number of birds (count 'em: one turkey, one goose, a brace of pheasants, four partridges, four woodcocks, a dozen snipes, four grouse and four widgeons) as well as a wide range of other ingredients (ham, tongues, bacon, truffles, and so on) contained within a massive pastry which is baked for six hours and then allowed to cool before serving.

According to Charles Elme Francatelli, who wrote an 1846 cookbook called The Modern Cook, "the quantity of game recommended to be used in the preparation of the foregoing pie may appear extravagant enough, but it is to be remembered that these very large pies are mostly in request at Christmas time. Their substantial aspect renders them worthy of appearing on the side-table of those wealthy epicures who are wont to keep up the good old English style, at this season of hospitality and good cheer."

Mince pies (with real meat)

Today, mince pies are one of the most famous of all the Christmastime confections. Although they're not exactly ubiquitous in the United States, they're incredible popular all over the world — and are practically staple foods during the festive season in countries such as the U.K. Quite famously, though, and despite their name, mince pies actually contain fruits and spices rather than actual meat. That's not how it always was, though.

Mince pies have existed since as far back as the 12th century. Back then, they contained commonly found meats spruced up with spices brought back from the Middle East by Crusaders. In medieval times, they were filled with meat (often rabbit) and topped with dried fruit. The meat version of mince pies remained the norm for hundreds of years, until they finally sweetened after cheap sugar became readily available as a result of the British slave trade in the West Indies. By the 19th century, they had become practically indistinguishable from the ones that are eaten today.

Beef and plum broth

While some Christmas traditions have managed to survive as they've passed further and further down the generations, others (thankfully) died out after everyone in the world collectively came to their senses. But there are a few surprisingly nice-sounding dishes that — for one reason or another — simply haven't survived to this day.

Take plum broth, for example. This recipe, which dates back to the 17th and 18th centuries, calls for a leg of beef and a slice of mutton to be boiled with prunes and spices. An hour later, throw in some raisins and currants and continue to boil, before seasoning with cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, ginger mace, salt and sugar. Add a twist of verjuice before serving with bread. The ingredients tended change slightly depending on what was available, but this sweet and savory dish served a big table — which was very common at the time. The beef/spices combination is slightly weird, we'll admit, but something about it does seem surprisingly tempting — it'd definitely taste like Christmas, that's for sure. Kind of a shame this one's gone, really.

Christmas Pudding (made with snow)

Russell Thacher Trall's 1873 book The New Hydropathic Cook-book: With Recipes for Cooking on Hygienic Principles was a healthy cookbook before healthy cookbooks were a thing — or at least, healthy according to the standards of the time.

His recipe for Christmas Pudding doesn't sound all that strange by today's standards... until you get to the part about replacing eggs with fresh snow, that is. According to Trall, snow contains a large amount of "atmospheric air" inside its flakes, which is set free as the snow melts. During winter especially, when eggs were scarce, it was a viable solution to having a tasty Christmas dinner — even without an important ingredient.

The recipe calls for wheat flour, sweet cream, raisins, currants, mashed potatoes, mashed, brown sugar, milk... and snow. No word on whether it actually tasted good, but it was affordable and the snow made it seasonable, right?

Twelfth Cake

The actual dish known as Twelfth Cake isn't that remarkable when compared to some of the other stuff olden days people used to eat. More curious, however, is the tradition that came with it. Twelfth Cakes were practically any large, sweet cake (or even smaller, individual cakes) that were traditionally handed out on the January 5: the Twelfth Night of Christmas.

The bakers would leave a token inside the cake, such as a dried bean or pea, a coin, or a flag on a stick. Whoever took the slice of cake which contained that token would be proclaimed king or queen of the day's revels. Other tokens could be used to appoint high-ranking officials to the "Revels Court," such as chancellor. By the time the cake was finished, you'd end up with what basically amounted to an entire micro-government, which remained set up for the duration of the party. Who ever said the past wasn't a fun place?

Lambswool

Full props to the pastos for this one — lambswool, despite its strange name and curious appearance, sounds nothing less than downright delicious. Its recipe makes an appearance in the poem Twelfth Night by Robert Herrick, which dates back to around 1648.

Lambswool is a mulled ale poured over hot apple puree (or, in some cases, whole apples or apple pieces cooked in spiced cider). The name is given to it likely because the puree resembled the wool of a lamb. It was a particularly useful recipe back then since it'd make use of the last of the season's apples, and could be prepared in a kettle rather than an oven, the latter of which was expensive to buy and maintain. The author Regula Ysewijn suggests that the inclusion of sugar in the recipe — still an expensive ingredient at this time — suggests that it might have been offered as a gift from lords to their servants, or from farmers to their laborers. It also may have been a popular drink for wassailers (Christmas carolers, if you will). Either way, if any of these recipes deserves a comeback, this has got to be it. Right?