What Grocery Stores Were Really Like In The '60s

In the 1960s, Beatlemania had taken the world by storm, women were walking around in a daring new garment called a "miniskirt," and protests were igniting across the country against systemic racism and the Vietnam War. It was a time of political turmoil and cultural revolution, but you wouldn't know if you went to any of the major supermarket chains. Grocery stores in the '60s were extensions of 1950s America, exhibiting traditional gender roles, analog technology, racial inequity, and culinary conservatism.

They also demonstrated the game-changing innovations of the previous decade. Plastic packaging, conveyor belt checkouts, and the very existence of stores that sold pretty much everything under one roof were still novel, and shoppers swarmed to their nearest Winn-Dixie or Red Owl to reap the benefits. In 1950, supermarkets accounted for only 35% of food sales for home consumption, as people continued to frequent butchers and bakeries and buy their milk from the milkman. By 1960, they accounted for 70% (via Progressive Grocer). From cocktail dresses to green stamps, shopping in the '60s looked pretty different from today, so let's take a trip down memory lane to marvel at just how much has changed.

The stores were much smaller

In an era of Costco and Walmart, it's hard to believe that supermarkets in the '60s were considered huge. The average size of a grocery store at the time was somewhere between 10,000 and 15,000 square feet (via Cheapism). Considering people used to buy from small shops selling limited categories of items from behind a counter, you can see how wandering through 15,000 square feet of aisles to select your own items could feel like the height of opulence. But those dimensions are dwarfed by the 45,000 square feet of today's average supermarket. Taking things to extremes, the average Costco is a jaw-dropping 146,000 square feet.

The size of stores in the 1960s meant that there were fewer products than we expect today. According to Consumer Reports, the average number of items in supermarkets in 1975 was just 8,948. In 2017, according to Market Watch, that number was somewhere between 40,000 and 50,000 items. Decision fatigue and losing a toddler were probably much rarer back then, but shoppers were forced to go to other stores to buy toiletries and homewares. Fewer choices meant people ate similar things, and anyone who ascribed to low-fat, vegan, low-sugar, gluten-free, or low-carb diets had to shop by omission rather than head to an aisle that catered specifically to their needs.

Most of the shoppers were women

These days, grocery shoppers are split fairly evenly by gender, but in the '60s, going to the supermarket was seen as a largely female endeavor. Middle-class women were still expected to stay home and out of the workforce, and family errands fell largely on their shoulders. According to historian Erika Rappaport, department stores in the late 19th century became one of the first places middle-class women could escape the confines of domesticity and exert their preferences in a public space. Less than a century later, supermarkets became another arena where housewives could assert their individuality and authority by choosing their families' meals.

Because of their buying power, women were the target of food marketing in this period. Ads appealed to their sense of responsibility as the family cook and nurturer while leaning into their need to balance the household budget. Many supermarket chains offered free childcare while mothers shopped, and the influx of frozen meals catered to those who needed all the convenience they could get to run a busy household and get food on the table seven days a week.

There wasn't always much of a produce section

If you wander into any grocery store these days, you will likely find that the produce section is right at the front, bursting with color and health. This is by design. When it comes to grocery shopping, first impressions are just as important as they are in dating and job interviews. Putting fresh fruits and vegetables at the front of the store colors a shopper's overall impression of their visit, making them think the store is overflowing with freshness and quality.

In contrast, the produce section in the 1960s was typically more of an afterthought than a marketing slam-dunk. In smaller stores, it only accounted for an average of 3% of the total floor space. By 1989, it was 15% (via the Packer). This disinterest in fresh fruits and vegetables wasn't just a holdover from previous decades. Throughout the '60s, consumption of fresh vegetables actually fell, from 106 pounds annually per person in 1960 to 98 pounds in 1969. If you were to walk into a grocery store in 1960, you would not have beheld a vast expanse of freshly misted fruits and vegetables glistening under dramatic lighting. Instead, if the produce section was at the front of the store, you would have seen a handful of products packaged in plastic to mimic the packaging of canned and frozen foods.

Meat was kind of a big deal

In place of the produce department, meat was the jewel in the crown of every supermarket. The manager of the meat section usually held an official place of authority in the supermarket's hierarchy, and the sales in that department dictated the overall financial health of the store. Chicken did not become popular until the '80s, but pork and beef more than made up for it.

After World War II, intensive farming practices developed alongside the expanding supermarket landscape to make red meat more available than ever. This, coupled with the fact that Americans were still living in blissful ignorance of the toll red meat was taking on their arteries, made it a beloved household staple.

Between 1960 and 1970, consumption of beef went from 64.2 pounds per capita to 84.1 pounds — an increase of 31% (via California Agriculture). In 2021, by comparison, Americans consumed only 59 pounds per capita (via Statista). The reason for the decline is complex, though it's likely that rising costs and an economic downturn in the late '70s, and research into the heart problems associated with saturated fat and cholesterol, had a combined impact. The 1960s was the last hurrah of the meat industry before it gave way to the low-fat craze of the '80s and the growing demand for fresh produce in the '90s.

Everyone looked like they were headed to a cocktail party

Fashion has changed dramatically over the years, but there's no getting around it: People used to dress a lot more fashionably to get their weekly quota of cereal and frozen dinners. Men who worked in the city wore suits, of course, but even women whose work was relegated to their homes and families would dress to impress. Pearl necklaces and high heels were standard, and gloves and fur were not nearly as out of place as jeans and sneakers would have been at the time.

In the 1950s and '60s, keeping up appearances was paramount, and for women who spent most of their time at home rather than at work, dressing up to go out was a matter of personal dignity and identity. Any public setting called for elegance, whether it was a college classroom, a movie theater, or a Piggly Wiggly.

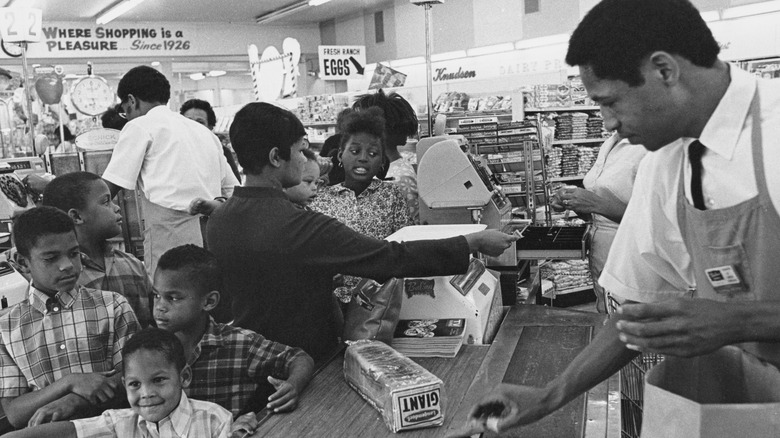

Most of the shoppers were white

For many Americans, the rapid expansion of supermarkets and the abundance of products they offered provided a new sense of freedom and modernity. But for others, they were off-limits. The '60s were a pivotal decade for the Civil Rights Movement. It saw the passage of the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, and the Fair Housing Act, all of which banned explicit forms of racial discrimination. But segregation continued through unofficial channels, and supermarkets were one of the most blatant examples.

As white Americans fled cities to the suburbs, supermarkets moved with them, all but deserting urban centers and largely Black neighborhoods. According to the Washington Post, one of the selling points of this new type of grocery store in the early 20th century was that it was a place where white women could feel "safe." Such coded marketing made it clear that Black shoppers were not welcome, even if they did live within a practical distance. As white suburbanites benefited from lower prices and more choices, many Black Americans found themselves with less access to affordable groceries.

Checking out took longer

We take a lot of grocery store technology for granted, but a quick outline of the check-out procedure in the '60s reveals how far we've come since then. After gathering the items they wanted to purchase, a shopper would make their way to the front of the store where a cashier would take each item and search for the price sticker. They would type the prices into a cash register and tally the numbers. The shopper would produce the necessary cash, and the cashier would produce change. Some supermarkets in the '60s boasted cash registers that automatically tallied change, but others still required human calculation.

In 1966, Kroger released a booklet in which it entreated industry innovators to create a more streamlined system. "Just dreaming a little," it said, adding "[C]ould an optical scanner read the price and total the sale. ... Faster service, more productive service is needed desperately. We solicit your help." It would be another six years before the first supermarket barcodes debuted at a Kroger in Cincinnati (via Smithsonian Mag).

Credit cards were another story. Although the concept of credit has existed for millennia and many shoppers were already shopping with store credit rather than cash, the little plastic cards that we so breezily tap at checkouts now did not become common until the 1990s when chips were added to ensure an encrypted scan that could be registered by both the merchant and the payment processing network (per Experian).

Organic food was nowhere in sight

Another feature of modern supermarkets, especially ones in urban areas, is organic food. From apples to cake mix, the organic label is a major selling point for brands, but it didn't exist until the late 20th century. Pesticide-free farming has existed since the dawn of farming itself, but the term "organic farming" wasn't used until 1940, when British aristocrat Lord Walter James Northbourne created the term in reference to a growing movement that pushed for more holistic farming practices and decried the use of pesticides and fertilizers. The term became a rallying cry among like-minded farmers and cultural figures throughout the middle of the century but given how difficult it was for supermarkets to sell fresh fruits and veggies in the '60s, it's no surprise that the general public showed little appetite for the budding organic movement.

By the end of the '70s, hippie culture was pushing new ideas of environmentalism into the public consciousness, and the idea of eating healthy, locally sourced, pesticide-free food started to gain traction. In 1980, a group of health food store owners in Austin, Texas, opened the first Whole Foods, which honed in on the natural and organic food market. A decade later, the U.S.D.A. launched the National Organic Program, which began awarding those now-familiar "U.S.D.A. Organic" labels to farmers whose practices fell within their guidelines.

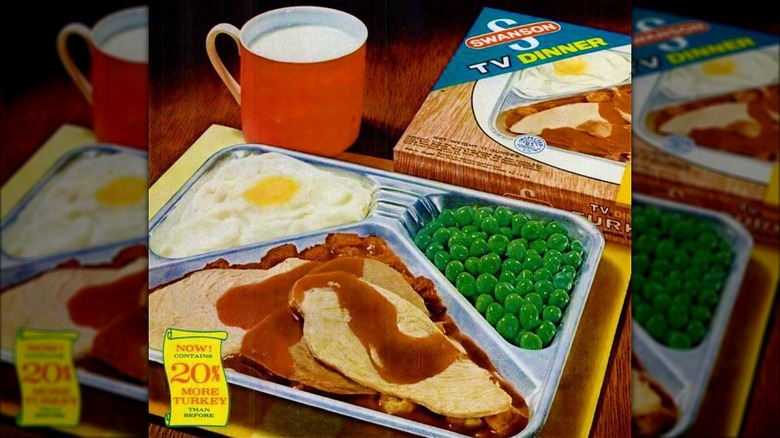

The frozen section was extremely popular

There is something irresistibly retro about a TV dinner. Sure, a reheated, factory-made meatloaf might taste like salty cardboard with a gluey side of mashed something-or-other, but there's a quaintness about it that makes it more of a novelty than a last resort. In the 1960s, TV dinners were nothing short of revolutionary. Swanson became the first retailer to offer frozen meals in supermarkets in 1954 (via Smithsonian Mag) after solving the issue of combining foods that cooked at different rates. Their first meal was turkey, peas, sweet potatoes, and gravy. For the price of $0.98 (via Love Food), it was a hit.

By 1965, the industry was estimated to be worth $5.2 billion. Sliding freezer doors had been invented, giving customers a better view of their ever-expanding options compared to the reach-down bins of the previous decades. The frozen meal craze also presented the opportunity for conservative, middle-class Americans to venture outside their culinary comfort zones and test "nationality" cuisines. Options ranging from chicken chop suey to "Polynesian Style Dinner" inserted some variation into the diets of suburban Americans and proved to be a marketing goldmine for manufacturers.

Frozen meals were a particular boon to the increasing population of middle-class women entering the workforce who were still expected to maintain the duties of housewives. There were reports of outraged men sending letters to Swanson to complain about the decline of home-cooked meals, but their voices were drowned out by dollar signs.

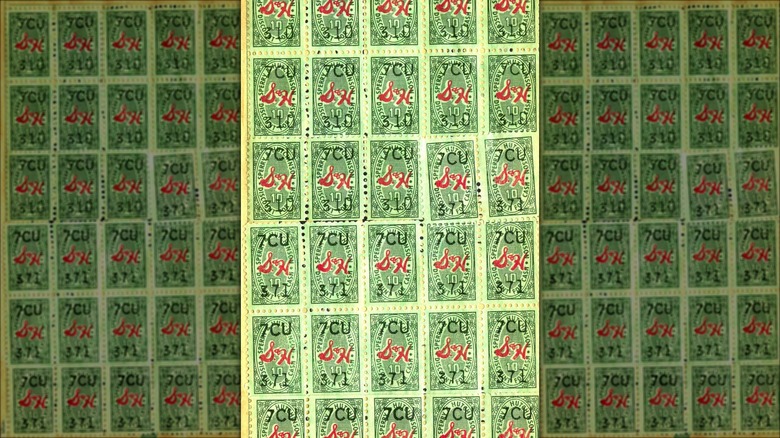

Green stamps were everywhere

If you were a consumer in the 1960s, trading stamps were as inescapable as dollars and cents. Created as an incentive for shoppers to pay with cash instead of store credit, stamps became a pervasive part of life in the 1950s and '60s. After a shopper completed a transaction, their cashier would give them a number of stamps corresponding to the amount of cash they spent. These stamps could then be collected in a redemption booklet and used as a form of currency to get a wide range of items from a catalog. S&H Green Stamps were the largest manufacturer of trading stamps. With a 178-page catalog, it was printing more stamps than the U.S. Postal Service at one point and collected by 80% of American households (via True Jersey).

The painstaking effort of sticking the stamps into neat rows in each 24-page booklet led to real-world value. In 1966, schoolchildren in Pennsylvania proved the point by collecting 5.4 million stamps to purchase a gorilla named Samantha for Lonesome George, a gorilla at a zoo in Erie. If all of this sounds a little too good to be true, it was. Trading stamps suffered a quick decline after the '60s when people realized the sticky currency was actually leading to higher prices. A wave of legislation restricting and taxing the stamps swept the country. The final blow was dealt in the Supreme Court, where one of the justices called trading stamps "an appeal to stupidity."

Canned foods took up significant space

In 1962, Andy Warhol elevated canned food to art when he produced 32 paintings of different Campbell's Soup cans. European critics praised the work as a Marxist critique of American pop culture, but as far as Warhol was concerned, it was just a depiction of what he ate for lunch every day. Many Americans could relate. In the 1960s, canned food wasn't reserved for natural disasters or power outages, but for everyday dining. It fed soldiers and cash-strapped families during World War II, and during the economic boom that followed, inventive branding and the promise of convenience kept its status intact.

During the '60s, Campbell's released SpaghettiOs and alphabet soup, and Starkist debuted Charlie the Tuna, some of the most popular products to hit the canned aisle. All of these brands are alive and well, but over time, shoppers fell out of love. Between 1972 and 2012, consumption of several canned fruits fell by 90%, while sales of canned fish and vegetables also fell precipitously (via Vox). Science surrounding the health benefits of freezing food at peak ripeness may be partially responsible for the uptick in frozen foods, while the general trend toward fresh produce — a category once ignored by supermarkets — continued to climb.

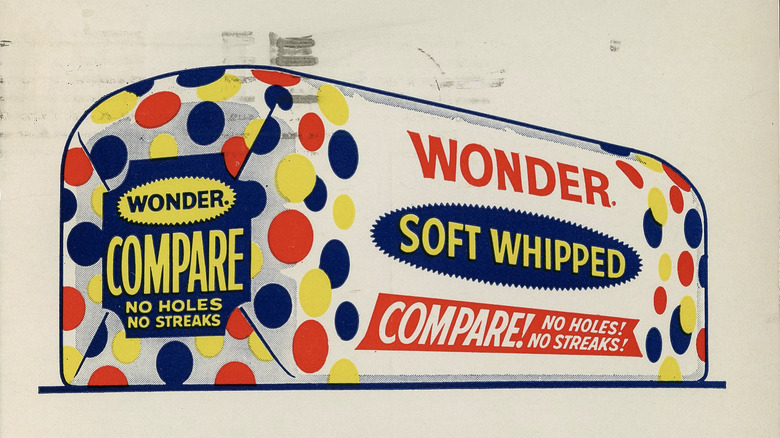

There weren't many whole grains

Americans weren't particularly interested in health food in the '60s. TV dinners, canned goods, and beef were all the rage, and any mention of whole grains would probably have been met with confusion. In the 1960s, less than 10% of bread sold in supermarkets was made from wholewheat (via WBUR). Ads for Wonder Bread promised children that the puffy white loaves would make them strong through added nutrients, while ads for Hostess Cream Filled Cupcakes claimed the sugary treat supplied 54% of "quick energy" and 46% of "reserve energy" for work and play, claiming that it was of value "particularly for children."

This marketing was curtailed in 1971 when the Federal Trade Commission tried to force the parent company of Wonder Bread and Hostess to apologize to consumers for their misleading health claims. Their suit did not pass the appeals process, but it was evidence of a larger trend. By the end of the '60s, the counterculture movement was pushing back on pesticides, chemicals, and the control that large corporations had over the country's diet. In the 1970s, so-called "hippie food" was everywhere, from brown rice to granola.

The stores were pretty smokey

It's hard to believe that smoking was once the norm in just about every public space. Whether you were spending an evening at the movie theater, sitting in a hospital exam room, or flying on a plane, you would more likely than not be shrouded in a veil of cigarette smoke. These days, only about 11% of Americans over the age of 18 smoke (per the CDC). In 1965, it was 45% (Smithsonian Mag). Movie stars posed glamorously with cigarette lighters, President Kennedy was often pictured puffing on a cigar, and teachers and students smoked on school campuses.

Grocery stores were no exception. Lighting up while perusing the options at the deli counter or fumbling through your purse at the cash register was second nature, and banning indoor smoking was still decades away. In 1967, anti-smoking ads appeared on TV for the first time, but there were still four times as many cigarette commercials on the air. It wasn't until research into the consequences of secondhand smoke was released in the '70s and '80s that policies began to shift. In 1974, the Board of Health approved a ban on smoking in supermarkets and elevators but refused to mandate non-smoking sections in classrooms.