The Untold History Of Schweppes, The World's Oldest Soda

From soda water to ginger ale and lemonade, soft drinks hold a special place in both our hearts and popular culture. Fizzy drinks are frequently our go-to choice for quenching thirst and finding moments of simple pleasure when water just doesn't cut it. They also make amazing mixers for spirits and cocktails.

While Coca-Cola holds the spot of the most popular soft drink in the world, it's far from the oldest one. In fact, the ubiquitous beverage was created more than a century after the birth of Schweppes and trails behind Vernors Ginger Ale, Moxie, and Dr Pepper in the age department.

Founded in 1783, Schweppes has been a pioneer in the world of fizzy beverages for well over two centuries. Revered as the oldest soda in existence, Schweppes' commitment to quality and innovation has left an indelible mark on the beverage industry, captivating the taste buds of several generations. Today, the brand's iconic logo is recognizable worldwide, while its products reach a staggering 811,000 individuals on a weekly basis and 6.5 million households annually, as reported by the Royal Warrant Holders Association.

Schweppes started out as carbonated water

Sparkling water was the precursor to the multiple Schweppes variants we know and love today. While the process for creating sparkling water was developed by the English scientist Joseph Priestly, the invention wasn't used for commercial purposes until it was embraced by watchmaker and jeweler turned-entrepreneur Jacob Schweppe in the late 1760s. After initially experimenting with the concept, Schweppe founded The Schweppes Company in 1783 in Geneva and started manufacturing Schweppes soda. The fizzy beverage was originally sold as medicinal water that replicated the qualities of natural waters from Seltzer and Spa, and later water from other regions, including Pyrmont, Vals, and Balaruc.

To expand the Geneva operations, Schweppe moved to London in 1792. Shortly after the move, he established the first Schweppes factory in the city. It also wasn't long before Schweppe's invention started being embraced by medical professionals, which was reflected in the brand's marketing. Schweppes Seltzer, for example, was marketed as beneficial for "persons exhausted by much speaking, heated by dancing or when quitting hot rooms or crowded assemblies." Meanwhile, Acidulous Soda Water was recommended for kidney and bladder issues, as well as indigestion and gout (via Difford's Guide).

Schweppes started coming up with sweet soda variants in the 1830s

Schweppes changed hands numerous times between its founder death in 1821 and the development of Schweppes Aerated Lemonade around 1835. While traditional lemonade, in the form of lemon and water, was already popular at the time, it had never been seen in a carbonated form. It wasn't until decades later, in the 1870s, that Schweppes launched Tonic Water and sweet and dry versions of Ginger Ale. Nevertheless, this was still much earlier than the brand's future competitors. To put things in perspective, Coca-Cola wasn't released until 1886, Pepsi until 1893, and 7UP until 1923.

The range of Schweppes mixers continued to grow in the 20th century. Schweppes developed its own version of Cola around 1916, when it first appeared on the brand's official price list. While Schweppes Cola is still available in some countries, its popularity has waned over the years due to stiff competition from well-established cola brands. Schweppes introduced its line of fizzy fruit juices during the 1920s and '30s, featuring flavors such as orange, grapefruit, and lemon. Meanwhile, the year 1957 marked the debut of Bitter Lemon and Bitter Orange as the newest additions to the brand's range of beverages.

The term soda water was first used in Schweppes' advertising in 1798

The term "soda water" made its appearance in Schweppes' advertising as early as 1798 — the same year Schweppe sold the majority of his share in the brand. This term became synonymous with carbonated water and played a crucial role in the naming and marketing of carbonated beverages. This is despite the fact that by the 1800s, carbonated water had already been around for over three decades, having been dreamed up by Joseph Priestly in 1767.

In addition to popularizing the term "soda water," the 1798 Schweppes advertisement provided a list of the brand's products and their respective supposed medicinal applications. Acidulous Soda Water, which came in single, double, and triple strengths, was recommended for indigestion, acidity, gout, the stone, as well as kidney and bladder problems. Seltzer Soda was recommended for nervous afflictions, feverish ailments, and biliousness. Meanwhile, Rochelle Salt Water was a laxative.

Schweppes was granted a Royal Warrant, which dramatically increased its popularity

Back in the day, supplying goods — including beverages — to the royal family was a big deal. To recognize the outstanding tradespeople and companies that were favored by the kings and queens, the British monarchy has been honoring them with a Royal Warrant of Appointment since the 15th century. The tradition carries on today, and companies that are granted this very special privilege are able to display the royal coat of arms on their products.

Schweppes was granted its first Royal Warrant of Appointment by King William IV in 1836, an endorsement which drastically increased the brand's popularity. After all, what's good enough for the royal echelon should be good enough for the general populace. At the time, the Duchess of Kent and Princess Victoria were also big fans of the fizzy beverage. In fact, it only took Queen Victoria two months after she ascended the throne in 1837 to grant Schweppes her own Royal Warrant of Appointment, keeping the company as the official supplier of soda to the monarchs. Notably, Schweppes still held its royal warrant at the time of the death of Queen Elizabeth II.

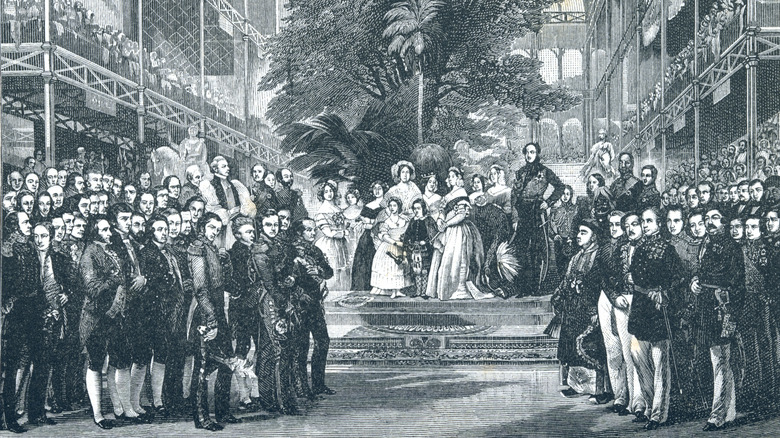

Schweppes was the official drink of the Great Exhibition of 1851

Attended by more than six million people over the course of six months, the Great Exhibition of 1851 represented a key moment in Schweppes' history. Billed as the "most successful, memorable, and influential cultural event of the 19th century" by The Gazette, the Great Exhibition was the first international event specifically held to showcase manufactured goods. The event was held in a giant purpose-built iron and glass structure called the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park in London.

When the representatives of the Great Exhibition issued a call for bids to supply refreshments at the event, Schweppes saw a huge opportunity — particularly since no alcohol was to be sold at the event. Investing £5,500 ($6,980) for the chance to sell its existing products, Schweppes also used the event to introduce its latest creation — Malvern Soda Water. In a bid to make a lasting impression, Schweppes erected a 27-foot crystal fountain made with 4 tons of pure glass that delivered a continuous flow of Malvern Soda Water.

The event proved to be a triumph for Schweppes, resulting in the sale of more than one million bottles of soda and triggering a notable increase in the company's overall sales. The image of the "Schweppes Fountain" continues to feature on the brand's logo up to this day.

Schweppes used innovative bottling techniques

Schweppes had once been at the forefront of innovation when it came to packaging its beverages. After all, keeping the bubbles where they belonged was essential for the success of the product. While it's not exactly clear what kind of bottle Schweppes initially used to package its soda water, there's a design for a stoneware bottle with a flattened base and two handles from a year before Jacob Schweppe moved to London.

Whatever bottle was used at the time, it seems that Schweppes started using skittle-shaped bottles in 1809, a design the company used for the next century. Also called "lighting in a bottle" and the Hamilton bottle in honor of its designer William Francis Hamilton, the skittle bottle had a rounded base and was designed to lay on its side. This is because the cork had to be continually saturated and expanded to retain the drink's bubbles. Schweppes gradually switched to using flat-bottomed glass bottles after the invention of the crown cork in 1892.

A new take on the original Schweppes bottle was a minor disaster

In 2017, Schweppes launched a new line of drinks called 1783 to commemorate the year the company was founded. The range of beverages came in skittle-shaped bottles that harked back to the company's original curvy packaging. Each bottle featured the brand's yellow Schweppes sash across the neck and its iconic fountain logo. Aside from traditional offerings such as ginger ale and tonic water, the line also featured more unusual flavors such as Salty Lemon Tonic Water, Quenching Cucumber Tonic Water, and Aromatic Floral Tonic Water.

The 2018 recall of the 1783 range demonstrated that sometimes the original is the best and shouldn't be tampered with. The recall, which affected some 600-milliliter glass bottles with a best-before date of 31 March 2019, was prompted by a flaw in the bottle's construction that could cause some of the caps to unexpectedly pop off, champagne-style. To prevent potential injury, Schweppes stated, "As a precautionary measure, we are asking all consumers who have one of these bottles to open it carefully to release the pressure, ensuring the bottle is pointing away from the body when doing so" (via iNews).

Schweppes is a pioneer of using word play in advertising

If you find the terms "Schweppshire," "Schweppsylvania," and "Schweppervescence" confusing, you're not alone. The three words are whimsical creations that play on the brand name Schweppes invented as a part of the brand's marketing campaign.

Used to describe the drink's distinctive fizzy quality, the slogan "What you need is Schweppervescence" was invented by the S.T.Garland advertising agency to promote the beverage after the shortages of the Second World War. The term Schweppervescence became so intertwined with the brand that Schweppes ended up paying Garland £150 ($190) for the right to use it in its future campaigns after the company moved its account to the Bloxham advertising agency.

The fictional British country town of Schweppshire appeared in the company's advertising between 1951 and 1965. The village, which was drawn by George Him and captioned by Stephen Potter, had its own set of characters, locations, language, and coat of arms. With six new advertisements released annually, Schweppshire relied on the tagline "Schweppervescence lasts the whole drink through" to increase sales — the product itself was never shown in the ads. Playing on the word Schweppes and Pennsylvania, Schweppsylvania was all about using humor to show the British public the intricacies of America's Keystone State.

Schweppes advertising showcases numerous celebrities

Just like many other brands that feature celebrities in their advertising, Schweppes has also leveraged the popularity of well-known personalities to promote its products. Over the years, the company has enlisted the services of several musicians and actors, capitalizing on their influence to create impactful advertising campaigns. Just some of the big names that have recently acted as Schweppes' brand ambassadors include Nicole Kidman, Iggy Pop, Uma Thurman, and Penélope Cruz.

Over the years, Schweppes' marketing campaigns have attracted their fair share of controversy for using sexually suggestive imagery. For example, a 2011 Schweppes commercial depicted a glamorous and skimpily attired Uma Thurman reclining on a chaise lounge, suggestively chatting with a French journalist. In the racy advertisement, the actress tells her visitor, "I love Schweppes and I need to have it all the time. I like to have Schweppes with strangers, I like having Schweppes at home, or sometimes in the taxi. And you, would you have some Schweppes, just me and you."

Schweppes has also enlisted Nicole Kidman and Penélope Cruz to appear in the company's "What did you expect?" campaign. Both advertisements use sexuality and the element of surprise to sell the product. In 2018, Schweppes took the innuendos in its "What Did You Expect?" campaign a step further by converting the slogan to "What Do You Expect?"