How Is Ketchup Really Made?

Ketchup or catsup? That is the question. Actually ... no, it's not (our shoehorned "Hamlet" reference notwithstanding). Because while some modern individuals do, in fact, choose to buck conformity by utilizing the bizarre, borderline-archaic term "catsup" when describing the bright red, sugar-soaked, uber-popular condiment, the far more common name of ketchup is the preferred terminology.

Now that we've fully established we're here to write about ketchup rather than catsup (there's nothing a food writer enjoys more than discussing culinary nomenclature), we can't help but wonder how much the world knows about this deliciously tangy, ubiquitously available condiment. More to the point, how many of us are aware of the precise process that transforms fresh tomatoes into the modern-day ketchup found on tables in seemingly every restaurant in the U.S. (and about 97% of U.S. homes as well)?

We may not be persuasive enough to sell a ketchup popsicle to a woman in white gloves (ketchup popsicle?). But uncovering the specific steps and procedures required to make ketchup, and relaying that information to the world, is squarely in our wheelhouse. So with our interest piqued regarding the beloved dipping sauce's production process, we decided to uncover — and, consequently, share with you — the answers to that timeless question: How is ketchup really made?

Ketchup always starts with tomatoes (at some point, at least)

Did you know the very first ketchup on record wasn't created in the U.S.? And it didn't contain tomatoes? You might. Though some are unaware of the centuries-long history of "ke-tsiap" (like the fact it was originally a fermented fish sauce created in China), the condiment's evolution isn't some ancient Chinese secret (huh?). Either way, once tomatoes became a dominant crop in the U.S. during the 19th century, the modern recipe was born, leading us to the fairly straightforward starting point for making ketchup: fresh tomatoes (or to-mah-toes, if you're so inclined).

Clearly, we're not providing any illuminating information by stating ketchup is a tomato-centric condiment that heavily utilizes the produce in its cooking process. But the bottom line remains that no 21st century version of ketchup can credibly use that name unless tomatoes — or, at least, what originally existed as tomatoes — are the main ingredient.

Since we're here to offer the full monty on how ketchup is made, then, we simply have to kick things off with tomatoes. Every bottle (or miniature squeeze packet) of ketchup begins its journey with fresh, whole tomatoes, after all, so that's where we start, too.

Tomatoes are initially cooked via the hot break method

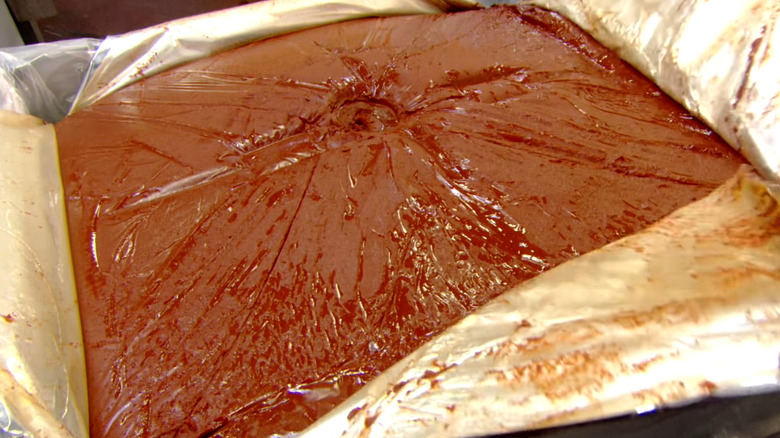

Despite any alleged opinions to the contrary, ketchup is not, nor will it ever be, a vegetable. This isn't solely because in botanical terms it's (maybe) a fruit, though — and it doesn't take Nancy Drew to recognize the final condiment has little in common with an actual tomato. But the drastic transformation from farm to fridge doesn't just happen. And one of the first steps in that process involves rapidly heating tomatoes to 200 degrees Fahrenheit to induce a hot break: a chemical reaction that breaks down enzymes while preserving pectin, a soluble fiber essential to the thickness of ketchup.

Since pectin is responsible for naturally maintaining the expected thickness of tomato paste — the common starting ingredient for many ketchup recipes – the heat break method is vital to producing a quality final product. Once a hot break occurs, the remaining liquid can be cooked off, leaving only the gooey tomato paste needed to make ketchup.

As noted, many recipes — including those used by some popular nationwide brands — start the ketchup-making process with an already-prepared paste rather than fresh tomatoes. In other words, knowing how tomato paste is created is essential to understanding how ketchup is really made, too.

The resulting tomato paste may be watered down before any further preparation

Anyone who's ever eaten ketchup — basically, everyone — realizes the condiment consists mainly of (what was once) tomatoes. Yet, as we previously mentioned, many manufactured ketchup brands actually start with an already-prepared tomato paste, not the fresh crop. This doesn't mean the thick substance is immediately tossed into a cooking vat, though. Instead, the tomato paste may be mixed with water first when prepared industrially, to help ensure a smooth consistency is retained in the final product.

Perhaps the addition of water seems, in theory, to defeat the entire purpose of initially cooking whole tomatoes down into a sludge-like paste. But this step is still considered crucial by some companies, including Heinz, in order to create the proper viscosity consumers expect when purchasing a bottle. We suppose we can understand that thought process because who wants to deal with a potentially chunky, barely pourable ketchup before digging into their burger and fries?

To be clear, not every ketchup is made by stirring additional water into a previously water-reduced tomato paste. Then again, this particular aspect illustrates a notable contrast in how homemade ketchup is often made versus store-bought versions (as we'll address momentarily).

Various spices and seasoning are added to the tomato paste

Given the sheer number of human beings walking the globe in the 21st century, we're sure there's someone in the world who prefers food products sans any seasoning or spices. But while Blandy McBlandenstein may be somewhere out there eagerly waiting to eat foods devoid of flavor, the rest of us realize the inclusion of, well, flavor is a necessity for enjoyment. Naturally, ketchup is no different, and a number of spices and seasonings are added to tomato paste (whether it's diluted or not) when making ketchup — often before any other ingredients.

Now, just which spices or seasonings one chooses to utilize when making ketchup tends to vary, particularly as it pertains to the many widely available brands on the market. In fact, some companies, like Heinz, appear to take precautions to protect the specific proprietary blend of spices used in its ketchup production — with Heinz treating its ketchup recipe as the condiment equivalent to KFC's infamously guarded 11 herbs and spices.

Still, thanks to the magic of food labels (and similar ingredients common in homemade recipes), we can ascertain some of the common spices likely added to ketchup, including salt and onion powder, among others.

Vinegar is mixed with tomato paste to prevent spoilage

Beyond the expected appearance of tomatoes in ketchup, no ingredient may be more widely associated with the dipping condiment than vinegar. This wasn't always the case, though. In fact, vinegar only became such a key ingredient in the food upon the exploding popularity of ketchup during the late stages of the 19th century. So when mass-produced ketchups of the day began spoiling far too quickly, the amount of vinegar was increased as a preservation technique — and the industry never looked back.

Vinegar's acidity isn't just invaluable to extending a batch of ketchup's shelf life, though. While that factor undoubtedly plays a part in its continual usage in large-scale ketchup production, the undeniable sourness imparted by vinegar has also become intimately associated with ketchup's flavor profile to the modern palate. In other words, there's a reason vinegar always appears in homemade ketchup recipes as well.

The precise moment in which vinegar is added when making ketchup — and which specific variety of vinegar one chooses to use — tends to vary depending on the recipe. Regardless of the timing, if you're wondering how to concoct an authentic ketchup? Be sure you have vinegar on hand.

Sugar is added to help balance the vinegar's sourness

The main reasons behind the overwhelming presence of added sugar in processed foods – as in, sugar in any form (not just white and granulated) — isn't all that difficult to decipher. For one thing, sugar's addictively sweet nature — and its similar-to-salt physiological impact on the human brain — is an easy culprit for its widespread usage. But the sheer delectability of sugar on its own also means it's often utterly essential (and expected) when eating certain foods ... like ketchup (surprise!).

Of course, we can't imagine it's surprising, per se, to any readers that sugar is prominently involved (and heavily used) when making ketchup. Given the tangy, sweet-and-sour taste iconic to ketchup — you know, the precise flavor you want rolling over your tongue when consuming it — it's hardly mind-blowing to learn that flavor can't be created with nothing but vinegar and spices.

Interestingly enough, the addition of sugar as a primary ingredient in ketchup is a direct result of the increased amount of vinegar used as a preservative in the late 19th century. Since the newfound sweetness was a hit with consumers (and concurrently inhibited any further microbial growth in commercial ketchup products as well), adding it became (and remains) standard for making ketchup.

The combined mixture is generally heated together for an extended period

Not every single food item or product needs to be cooked or heated before consumption — a fact that isn't limited to whole, naturally grown foods. Still, even if the preparation for certain foods doesn't require long-term cooking, there are benefits to be derived from allowing ingredients to stew together for an extended period of time. With that in mind, it's no wonder making ketchup often involves simmering the combined ingredients over heat before bottling (or ingesting) it.

We may be alone, but we think it's fairly obvious why a commercially produced ketchup brand — such as OrganicVille — would prefer to heat its ketchup when making it (rather than just mixing, and selling, it cold). This helps minimize the risk of bacteria developing in a batch before it reaches store shelves, after all, thus lowering the chance the product will lead to food poisoning in any customers.

Has every single solitary batch of ketchup that's ever been created (be it in a factory or in one's own kitchen) been cooked at some point? Not necessarily. But for the most part, there's a strong likelihood that a heating phase of some length is to be expected when ketchup is made.

The process may vary slightly between industrial-produced brands and homemade recipes

The notion that a nationally (or internationally) available product — one produced in gigantic factories at mind-boggling speeds — isn't made in the exact same manner as one you're cooking at home shouldn't be shocking. And, to be sure, we've certainly hinted that slight variations exist between the step-by-step process for commercially sold ketchup products when compared to homemade varieties. Now, allow us to clarify the hopefully inferred message regarding the two main options for making ketchup: They aren't identical.

That's not to say the two processes are wholly devoid of any similarities, of course. But there's simply no way around the fact that no home setup can rival the sheer size of an industrialized process — and there are plenty of logical reasons why that is, logistically speaking.

Additionally, we're not picking sides in the so-called battle between large-scale ketchup productions versus small, personally prepared versions. Rather, we're just presenting the facts as we've uncovered them, and hope it's clear that how a ketchup is made will vary depending on the type you're discussing.

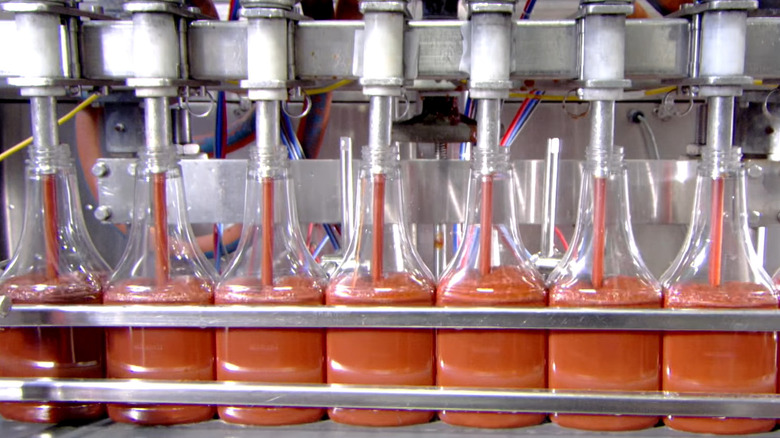

Industrially made ketchup is tested to ensure the proper viscosity

One of the more fascinating discoveries we made during our research was a specific quality test used by some of the world's most popular ketchup brands. In fact, before a commercially made ketchup is bottled and shipped to stores, a company is likely to test each batch's viscosity first — ensuring that brand's product offers the thick-yet-smooth texture consumers know, love, and expect from ketchup.

Frankly, the specifics surrounding the viscosity test used by Heinz — one conducted to determine whether the ketchup in question will be allowed to reach the bottling stage — are exceptionally interesting (perhaps we're just food nerds, though). After the company's famous ketchup has finished cooking, a spoonful of the red stuff is scooped into a small, metal, downward-sloping contraption. The ketchup sample is then released and timed for 10 seconds — with only samples clocked as moving at less than 0.028 miles per hour finding their way to hungry customers.

While it's unclear just how other brands test the viscosity of ketchup, given the universal expectations surrounding the look and feel of commercial ketchup products? We'd bet tests at least somewhat similar to Heinz's own version exist across the marketplace.

Some ketchup brands may add a thickening agent

Very few commercially made ketchup brands hit the market without being tested for the proper viscosity. Yet not every food company is likely eager to simply dump a batch of less-than-ideal ketchup (viscosity-wise, we mean). So along those lines, some companies may instead make use of modern food additives by introducing a thickening agent of some sort, like xanthan gum, to achieve the desired consistency.

Can we say with any real certainty which (if any) prominent and well-known ketchup brands are apt to follow the tenets of molecular gastronomy when it comes to thickening the condiment? Nope. But given the seemingly endless number of both natural and artificial food additives found in excessively processed foods — like, say, ketchup — we'd be stunned to discover a complete absence of such thickening agents in every available brand of ketchup.

It's not necessarily a bad thing to learn that thickeners, such as potato starch, may be present in ketchup. Still, if you're truly concerned about artificially thickened dipping sauces? At least you can be wary of any non-homemade ketchups in the future.

Certain homemade ketchup recipes don't require any cooking at all

When we first set out to answer the question at hand — how is ketchup really made — we had a certain set of preconceived expectations. Namely, we were of the mind that concocting any sort of ketchup, even one at home, would involve a step or two of actual cooking. But part of the joy in researching food-based information is when the truly unexpected is uncovered — like the sort of stunning fact that not all homemade ketchup recipes require cooking at all.

Now, to be clear, even a recipe sans any additional heat still utilizes a previously cooked item with the tomato paste (made via the heat break method, remember?), meaning no ketchup is likely completely compatible with a raw diet. But we can't pretend we ever expected to learn some simple ketchup recipes skip over any further cooking procedures entirely, simply urging home chefs to mix the suggested ingredients ... and enjoy.

Homemade ketchup may need to be emulsified and strained before serving

While some homemade ketchup recipes appear content with simply adding various ingredients to room-temperature tomato paste then calling it a day, others are a product of time and effort. In that sense, depending on the recipe — like, say, a spicy ketchup variety — you may not be able to enjoy the final product until you've ironed out all the wrinkles. Or, to be more accurate, until you've fully strained and emulsified the presumably chunky byproduct cooking in a pot on your stove (or in your slow cooker).

Perhaps you're enthralled by the notion of eating an unusually lumpy ketchup — one that's closer to salsa than a ketchup bought at the store (depending on the ingredients used, that is). But if you're hoping to enjoy a homemade ketchup with a texture even remotely akin to industrial-made brands, you should plan to make use of your handheld emulsifier and strainer in the process.

Quite frankly, anyone hoping to emulate a store-bought ketchup at home will likely need to strain away any excess chunks, and blend the ingredients to achieve the desired consistency — unless you're aiming for a salsa-and-ketchup hybrid rather than simple ketchup (in which case, all the power to you!).