The Tragic, Real-Life Story Of Colonel Sanders

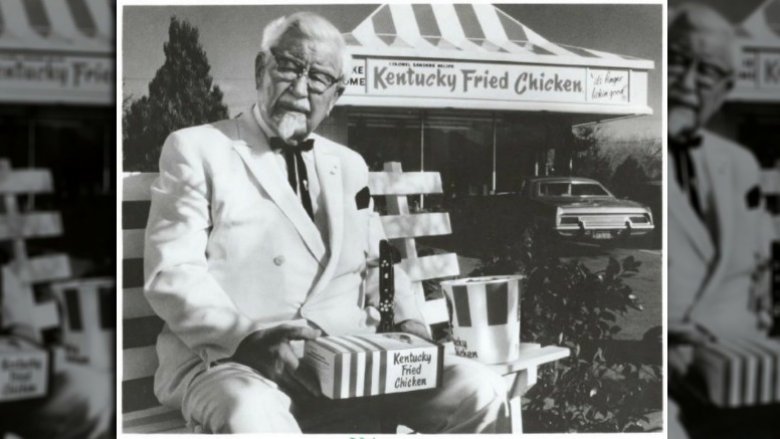

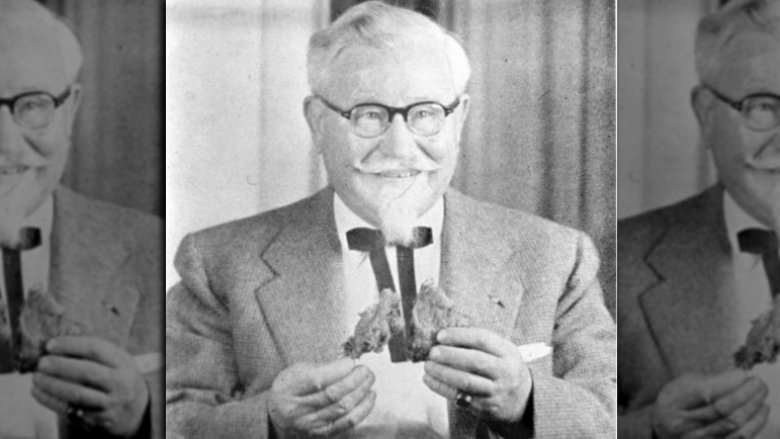

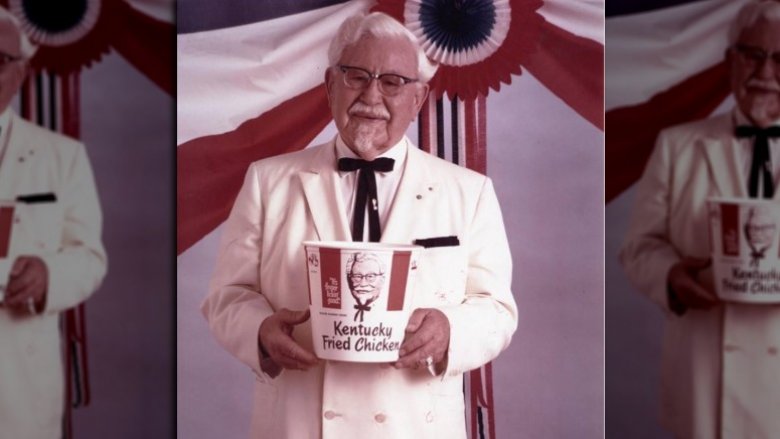

Colonel Sanders is probably the most recognizable icon in fast food history. His face — which is now synonymous with fried chicken across America and the wider world — has been a part of the KFC brand since KFC was a thing, and it's hard to imagine the company without its treasured mascot.

Although his face is practically everywhere, however, most people don't know too much about the man himself. Much of what you may have heard — that he attempted suicide after a series of business failures, that he once tried to kidnap his own daughter, that he eventually retired a billionaire — is little more than myth, perpetuated across the internet for the purpose of inspiring LinkedIn entrepreneurs and bored Baby Boomers on Facebook. The genuine story, however, is infinitely more interesting, more satisfying and more utterly tragic. Forget the fiction: This is the real-life story of Colonel Harland Sanders.

Colonel Sanders didn't have a very good start

Colonel Sanders was born in 1890 on a little farm in Henryville, Indiana. His father, Wilbert Sanders, died only five years later, forcing his mother to take work at a local tomato canning factory and sewing for nearby families, often away for days at a time. In the meantime, Sanders, who was the oldest of three siblings, was forced to take care of the home and his family — this is when he started to develop his cooking skills.

At the age of 10, he took his first job at a local farm. When Sanders was 12, his mother remarried and took her children to live with her new husband in the suburbs outside of Indianapolis. His relationship with his new stepfather was strained, to say the least, and the two fought often. Finally, at the age of 13, things came to a head at home and Sanders was sent back to Clark County, where the family had first lived.

Colonel Sanders had a hard time holding down a job

Colonel Sanders soon scored a job working on a farm in Greenwood, Indiana, earning $10-15 a month, plus room and board, feeding animals and performing odd jobs. Around this time, Sanders (who'd been balancing his farm work with a full-time education) dropped out of school, only completing the sixth grade. He'd one day claim that "algebra's what drove me off."

Over the next 28 years, Sanders would take on an incredible number of different jobs across the American south. These included a brief stint in the U.S. Army (during which he was sent to Cuba), as well as working as a streetcar conductor, a railroad fireman, an insurance salesman, a secretary, a tire salesman, a ferry operator, a lawyer, and even a brief stint as a midwife (really!). Some of his career highlights included getting into a fistfight with his own client during a court case and leaving the ferry business after the construction of a nearby bridge put him out of work. As he left his youth and entered middle-age, it became increasingly likely that Sanders would never achieve the success which his hard work demanded.

Colonel Sanders' family life was full of tragedy

Colonel Sanders' own family life was often tumultuous and occasionally fraught with tragedy. In 1908, he married Josephine King, a woman with whom he had three children: Margaret, Harland Jr., and Mildred. His inability to hold down a job soon proved troublesome at home, however, and Josephine wound up leaving him for a short time — and taking the children with her — because of his career woes. They divorced in 1947.

Disaster struck again when Harland Junior died at the age of 20 of complications from blood poisoning he contracted during a tonsillectomy — what was commonly regarded as a simple, routine procedure, even at the time. According to John Ed Pearce, one of the Colonel's biographers, Sanders was afflicted with depression for a period during his adult life. Frankly, it's not difficult to see why.

Finally, in 1949, he married a woman named Claudia Leddington, who he would remain with until his death in 1980.

Colonel Sanders finally had a taste of success

Eventually, Colonel Sanders ran a gas station in Corbin, Kentucky. To make ends meet, he began to cook and sell meals for weary travelers who stopped at the station. His food, which usually consisted of pan-fried chicken, ham, string beans, okra and hot biscuits, garnered him something of a reputation in the region for his skills as a chef. It wasn't glamorous work, but it landed Sanders the one thing he'd never found in his life: success. It was a modest yet satisfying life for the Colonel. A few years later, he took out the gas pumps and set up his first restaurant.

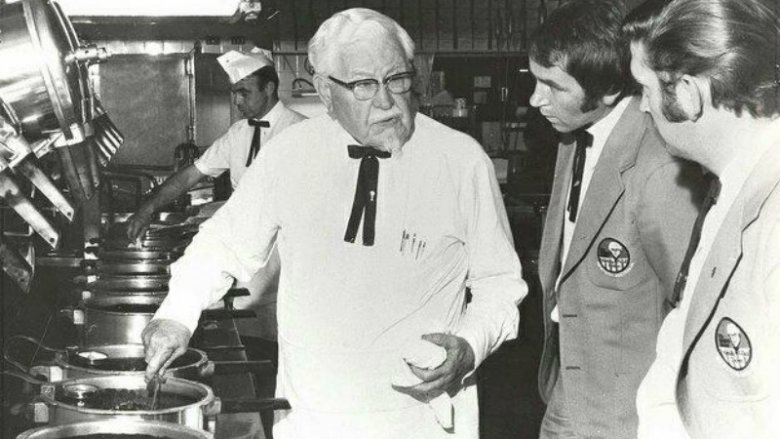

By this time, Sanders had begun to perfect the recipe for chicken which is still closely guarded by KFC today. His winning streak grew even hotter in 1939, when he developed a method of cooking chicken via a pressure cooker which cut down on grease and preserved flavor, moisture, and texture without sacrificing cooking time. For over a decade, Sanders' restaurant prospered — but another bout of tragedy waited on the horizon.

Colonel Sanders went back to square one

In the '50s, Colonel Sanders was struck by two blows of bad luck in rapid succession, putting the success he had finally found at great risk. The first came when the highway junction situated in front of his restaurant was moved to another location, effectively putting an end to the busy traffic which regularly passed by — and provided him with customers. That alone would be enough to put a major dent in his business, but next came the announcement of a brand new interstate highway which was to be built on a location which bypassed the restaurant by seven miles. It became clear that Sanders and his restaurant were about to be left in the dirt.

Sensing the end was near, Sanders auctioned off the site of his restaurant in 1956, and he took a loss on the sale. With no income, he was forced to scrape by a living on his savings, the proceeds of the auction, and his Social Security check of $105 per month. After a brief and tantalizing flirtation with success, Colonel Sanders was back to square one.

Life on the road for Colonel Sanders

After the closure of his restaurant, Colonel Sanders, now devoted to his cooking, attempted a new business tactic. He traveled across the United States, visiting potential franchisee restaurants and offering them his chicken recipe in return for 4 cents on every chicken sold (he later raised it to a nickel). Sanders' first franchisee was Pete Harman, a friend in Salt Lake City, who had seen a boom in sales since beginning to serve chicken made with Sanders' method and recipe.

It would not have been an easy life. Sanders would wander across the country, always on the lookout for suitable restaurants. If he found one, he'd walk inside and try to convince the owner to let him cook some chicken for the restaurant's employees. If they approved, he'd suggest cooking for the restaurant's customers for a few days. The public would then, theoretically, so enjoy this new recipe that the restaurant would enter into negotiations to begin franchising for Sanders. It was a slow, expensive, and humiliating way to pursue business partners, and in the meantime Sanders (and sometimes his wife) lived out of his car and ate begged meals from friends whenever he could.

But it worked: By 1964, he had franchised over 600 outlets and built a company worth millions of dollars. Although, at that time there weren't actually any Kentucky Fried Chicken locations, only restaurants that sold their chicken.

Colonel Sanders sold out

At the age of 74, Colonel Sanders owned a thriving company with 17 employees, an office, space and a not inconsiderable profit margin. Naturally, it attracted predators. John Y. Brown, Jr., was a 29-year old lawyer from Kentucky who, with his millionaire patron Jack Massey, set out to convince Sanders to sell his company. The Colonel, at first, firmly declined their offer. Brown and Massey then spent weeks attempting to persuade Sanders into changing his mind. They told him he ought to retire and enjoy life, that if he died before selling his estate would be ravaged by taxes. They swore to never tamper with his recipe and insisted on the highest degree of quality control for the franchise.

Sanders, who believed KFC to be his own child, remained hesitant. He, Brown and Massey toured the country, consulting family members and business associates. In 1964, he gave in to their offer of $2 million. Sanders would receive a down payment of $50,000 in the sale, the company's assets in Canada, and a lifetime salary of $40,000 per year. To get it all, though, he had sacrificed the most important thing in his life — and no indication exists that he was ever truly happy with the deal.

Colonel Sanders fought with the company after the sale

Colonel Sanders' role in the ever-growing company wasn't over, though. Brown believed Sanders' face to be KFC's greatest asset and instigated a serious publicity campaign to up his nation-wide presence. He appeared on television, conducted press interviews and visited individual restaurants as a spokesperson for the company. In 1971, Brown sold the company to Heublein Inc., and Colonel Sanders became discontented with the direction KFC was taking: the company moved its headquarters to Tennessee, began charging a franchise fee for its outlets and took a percentage of sales rather than Sanders' preferred rate of a nickel per chicken.

Eventually, Sanders chose to open a new restaurant which he named Colonel Sanders' Dinner House. KFC posited that they owned the rights to his name and threatened legal action. He renamed his eatery to the Colonel's Lady's Dinner House, but KFC insisted they owned the rights to the word "colonel." Sanders then decided to sue the company he began — for $122 million. KFC responded by suing him for trademark infringement. They settled in 1975 and the terms have not been disclosed.

He got in trouble with the company again in 1978, when he gave a newspaper interview complaining the gravy now tasted like "wallpaper paste" and the new chicken recipe was horrible. The franchise where he gave the interview tried to sue him for libel, but since he was talking about the whole company and not just one location, the judge threw it out.

The final years of Colonel Sanders

Despite his troubled relationship with KFC, Colonel Sanders continued to work for the company for the rest of his life. According to his grandson Trigg Adams, "to him, life was work." Sanders had never known a life before work — he'd been at the coalface, so to speak, for almost 80 years — and it was clear that he wouldn't accept a life after it, either. He continued to tour the country on KFC's behalf and, for the last two decades of his life, was never seen in public wearing anything but his iconic white suit. In his later years, he also found religion — occasionally appearing on evangelical Christian television shows — and donated much of his wealth to charities, such as the Salvation Army.

On December 16th 1980, Sanders died of leukemia at the age of 90. His body was ordered to lay in state at the Kentucky State Capitol, before he was buried in Louisville, Kentucky.

Colonel Sanders left a fractured legacy

In the wake of Colonel Sanders' death, KFC's fortunes exploded. It became one of the US's leading fast food brands, opened up thousands of restaurants across the world and, in the fourth quarter of 2017, enjoyed a net income of $436 million dollars. That success, however, came at the cost of the destruction of the Colonel's image.

KFC's mascot became little more than a marketing tool, who at one point even became a dancing cartoon character who dunked basketballs and plugged Pokémon toys. The company — once Kentucky Fried Chicken, now KFC — has even attempted to distance itself from its southern roots in recent decades. Sanders' family now has nothing to do with the company whatsoever. Although in the last couple of years KFC has attempted to levy a new sense of respect onto Sanders' brand, it's hard not to wonder what the Colonel — a man who believed in hard graft, held his own quiet dignity and distrusted large corporations — would make of the company today.