How The Invention Of TV Changed Food Forever

In a pivotal scene in "The Strategy," one of the best episodes of "Mad Men," Peggy Olson pitches a commercial for Burger Chef, a fictional 1960s-era fast food restaurant. According to Peggy, it's a place where people can go where "there's no laundry, no telephone, and no TV."

In the scene, she reminds her colleagues and her would-be Burger Chef account associates that, in most homes, the TV set is only about six feet away from the dinner table. She also reminds them that the only way to avoid the TV and get a family conversation in edgewise is to leave that dinner table and go eat at Burger Chef.

In a world where fact is often stranger than fiction, H.G. Wells, writer of the sci-fi invasion classic "The War of the Worlds", probably never imagined that the machine Peggy Olson talked about would invade most homes in America. What's more, likely even Wells himself couldn't fathom that we would willingly let this intruder in. Because it's so ubiquitous in our lives, few would think of TV as an invader in our homes and even fewer could have predicted the effect it would have on advertising, culture, and even food. Here's how TV sometimes dramatically changed all of that.

People's TV habits nearly shut down restaurants

During the 1940s, Americans endured the privations of food rationing. There was only so much sugar, flour, and other staples to go around, given that the U.S. government needed to feed millions of soldiers overseas. Yet American restaurants enjoyed up to 30% more ration coupons than the average household, making a lunch out a welcome treat. Simultaneously, business expense accounts began to grow. While employers didn't have the cash to pay workers more, they could write off employees' lunches. To say restaurants boomed during the war and the years afterward is an understatement.

When restaurant patrons and their money started to trickle away after the invention of TV, restauranteurs were left reeling. It seems that people wanted to watch TV more than they wanted to fill restaurant booths. It's important to remember that VCRs and streaming did not exist yet. TV in the 1950s offered limited programming and few stations. If people wanted to watch their favorite show, they needed to watch it right then and there.

In the war between restaurant profits and TV viewing, TV nearly won. It was only when delivery and drive-through became more common that restaurants' dipping profits perked up again.

Carhops, drive-throughs, and delivery surged in popularity

In the 1950s, the interplay between car culture and the invention of TV changed how Americans lived and ate. During that era, people consumed as much television — an estimated four hours and 35 minutes a day — as they did gas and fast food. More and more people wanted to order their food and take it elsewhere to eat. Often, that was in the car or at home in front of the TV set. And if people could get their food and never leave their cars in the process? Even better.

Restaurants caught on quickly. If customers didn't want to go to the restaurant table to order, then the table would come to them. This was the era of the carhop, the precursor to the drive-thru window. Carhops began to fade away when, in 1948, drive-thrus hit the scene.

But it wasn't just carhops and drive-thrus that restaurants implemented to bolster lackluster sales. They also took to TV advertising to show off the menu items that tasted just as good at home as they did in the restaurant. People only needed to order, then swing by to pick up their food or have it delivered. Food to-go and a speedy car saved many a night of TV-watching.

Sales for refrigerators and other kitchen appliances spiked

By the 1940s, 85% of households had a modern refrigerator (or at least what passed for modern then). By the 1950s, the American housewife was surrounded by any number of modern gadgets to help her make the recipes she found in magazines like The Ladies' Home Journal. What she didn't have was a constant reminder of why she needed such things in the first place. That is, until TV advertising swooped in to rescue her from her refrigerator-less life.

Not surprisingly, the invention of TV advertising caused an advertising explosion. Fortunately for the manufacturers of refrigerators and other kitchen appliances, the sale of domestic implements exploded right along with 1950s TV advertising. In those post-Depression and post-World War II years, the good American was the consuming American, after all.

But sales of refrigerators did more than make for good Americans. Before the fridge's invention, women spent a good deal of time canning, drying, and planting to ensure that food was always on the table. Without the threat of rotting vegetables going to waste in the icebox, women were free to follow other pursuits, including possibly working outside the home. It's probably no coincidence that Tupperware home party sales took off during that era, too.

Frozen TV dinners became a thing

Some dispute has arisen over the years about how TV dinners got the name. One version of history says that they were so named because their shapes looked suspiciously like a TV. Other stories have Gerry Thomas, the man credited with inventing TV dinners in 1953 for C.A. Swanson & Sons, saying that he wanted to use the new popularity of TV to sell his product. Whatever the truth is, what's not in dispute is the fact that lots of people have since eaten these meals in front of the TV since they debuted.

The first TV dinners featured turkey, a way to deal with Swanson's excess of more than 500,000 extra pounds of turkey after Thanksgiving 1952. The meal also included sweet potatoes and peas. Busy moms, as well as people who get creeped out when different foods touch, rejoiced at the sight of those compartmentalized trays that kept each item separate for the duration of the meal.

The foil tray also allowed these quick dinners to go from freezer to oven in less time than it took to whip up a martini. What's more, there was no slow burn with this dish. Millions of piping-hot compartmentalized trays of tatery goodness sold in their first year of existence. For nearly a decade after their invention, TV dinners became a once-a-week addiction for many households until the convenience of fast food dimmed the light on TV dinners.

TV trays took people from the table to the couch

The wheel. The pyramids. TV tray tables. If you're looking at this list and wondering what each has to do with the other it's this: all three changed the human experience, yet no one knows who created them. Given how close the modern TV tray table is to us in history, you'd think that someone, anyone would raise their hands to take credit, but this is not the case. We at least know that these small, portable trays were in many living rooms by 1952.

Basically, Americans went from standing on the Western Front to sitting in front of their TVs in a mere seven years. They barely had enough time to adjust to going from European dirt mound to kitchen table before the couch and their trusty TV Guide, the era's best-selling periodical, beckoned them.

Certainly, the view looked better. Programs like "The Honeymooners" flickered on postwar TV sets, while the trays in front of viewers sported flowers, paisley patterns, or other pretty designs. Later on, when TV producers got smart, they licensed the rights to TV characters like the Incredible Hulk, the Smurfs, and Superman to create a decor trend that might be best described as "Late-Century TV Land."

TV character lunchboxes and other toys exploded in popularity

Tucked in a back room of the Rivermarket Antique Mall is a place that conjures up pleasant memories from school lunches past. It's the Lunchbox Museum, containing about 450 metal lunchboxes. These aren't lunchboxes so much as they are small metal time machines decorated with the faces of cartoon characters and superheroes. A "Steamboat Willy"-era Mickey Mouse was the first character to get his own lunchbox way back in 1935.

But the real heyday for branded metal lunchboxes started in the 1950s when characters like Hopalong Cassidy hopped out of the screen and into lunchtime. This type of character lunchbox served as carry-along advertisements for a highly-targeted and somewhat captive audience: school kids in the cafeteria.

Savvy TV execs didn't just push lunchboxes during this era. If a character had kids' attention, it eventually became a doll and often decorated items like drinking glasses and pajamas — all supported by TV advertising. Sadly, Silvester Stallone's "Rambo" ushered out this era of metal character lunchboxes when manufacturers decided plastic boxes were safer and cheaper to make.

Ronald McDonald got his own TV show

In many towns across the US, the Ronald McDonald House serves as the only tangible reminder for many people that McDonald's once had a red-lipped clown mascot that the chain used in ads to entice kids to pester mom for a Happy Meal. Ronald and his string of cartoon character friends, including the Hamburglar and Grimace, livened up McDonald's ads in what was called the McDonaldland universe.

At least, they did until 2016, when the company's "I'm lovin' it" campaign encouraged adults to forget about Happy Meals for the kids in favor of buying themselves lunch. McDonaldland didn't exactly fit into a more grown-up version of the fast food chain that McDonald's wanted to portray.

But in the years leading up to this demise, Ronald and friends had quite the time starring in TV commercials and their own TV show and direct-to-video releases in the McDonaldland universe. McDonald's originally tapped Sid and Marty Krofft, the makers of "H. R. Pufnstuf," to create a show with a similar puppet-y vibe. That project fell apart but not before McDonald's produced its own Pufnstuf-like show, a feat that landed them in court for copyright infringement when the Kroffts contended that McDonaldland mayor, Mayor McCheese, looked suspiciously like H.R. Pufnstuf.

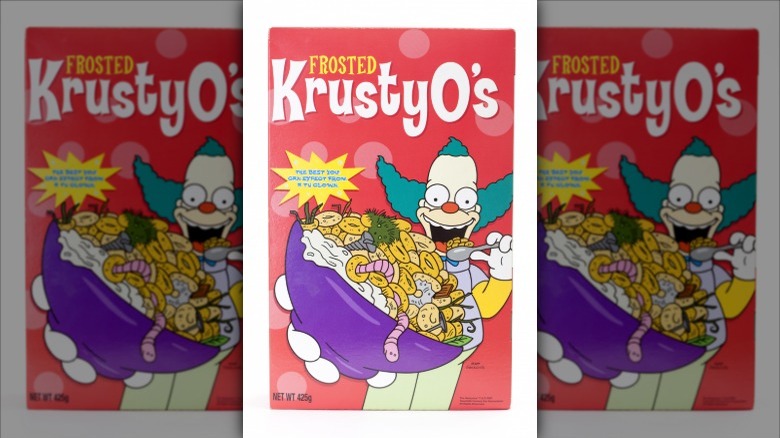

TV shows spawned breakfast cereals

Regular attendance at Saturday morning cartoons represented a significant achievement in the history of youth. At a stage when most kids' growing bodies discourage them from waking up earlier than 8:30 a.m., many woke up as early as 6:00 a.m. and stationed themselves in front of the TV waiting for their favorite cartoons to start. The luckiest among them had a secret weapon that helped them wake up: sugary sweet breakfast cereal with the face of their favorite cartoon character on the front.

Over the years, a slew of TV characters like Krusty the Clown, from "The Simpsons," Steve Urkel from "Family Matters," Dino from "The Flintstones," and even the Addams Family lent their mugs to cereal boxes not only in the U.S. but also in other parts of the world. Many of the cereals, like Urkel-Os, had an intentionally limited run from the get-go, making the urgency to eat them all the more pressing. Others, like 2001's "Xena: Warrior Princess" cereal, never even made it to store shelves. Instead, they were marketed directly to fans of the show at comic shops.

It created modern sports bar culture

Jimmy Palermo of Palermo Tavern is thought to be the creator of the first sports bar, which opened in 1933 in St. Louis, Missouri. There, beer flowed as generously as sports talk did. Palermo cited the addition of television to his bar as what turned his pub into a bonafide sports bar ... well, that and all the gameday food on the menu, like ballpark hotdogs and pretzels. Eventually, like all great ideas, the idea of the sports bar spread beyond the walls of the Palermo Tavern.

Cable TV programming cranked the sports bar experience up a notch, meaning people flocked to sports bars to watch games they might not otherwise have seen if it weren't for the bar's cable subscription

In 1980, the "Big Three" networks (ABC, CBS, and NBC) dominated most people's TV options, while only 23% of people had cable. By 2015, however, 76% of people had cable access and, presumably, plenty of sports progamming along with it. What's more, that doesn't even cover streaming services. It all means that most people don't need to go to a sports bar nowadays to watch the big game. What's more, gameday food in the sports pub costs more than many want to pay. It all means that modern sports fans are more likely to cook wings at home while they watch the game on a big-screen TV.

TV cooks and celebrity chefs were born

These days, famous TV chefs are everywhere. Guy Fieri treks far and wide to out-of-the-way roadside diners. Julia Child introduced us to French cooking. Eric Adjepong talks about international cooking on CBS Mornings. However, in the not-so-distant past, the thought that TV chefs would make the news at all would have been unbelievable. But, like so many other aspects of food culture, TV changed everything.

On June 12, 1946, in a cooking show that was all of 10 minutes long, British actor and eventual TV chef Philip Harben taught viewers the finer points of cookery in a show aptly named "Cookery." Ten minutes eventually became 20-minute episodes that aired over five years.

This first cooking show counts as one of the miracles of food history, given that World War II food rationing was still in play when Harben began cooking on TV. It wouldn't be long before the idea caught on. In August 1947, the idea of the cooking show crossed the Atlantic when James Beard's "I Love to Eat" hit the airwaves. Those two programs laid the foundation for the world of celebrity chefs that we know today.

Food channels now deliver programming all day and night

Much to the delight of foodies everywhere, food culture has come into its own. This has largely to do with the Food Network plastering food, food, and more food on TV 24 hours a day, seven days a week. It's easy to say now, well, of course! But that's only because hindsight is 20/20. When Reese Schonfeld, a co-founder of CNN, put his weight behind the idea, few imagined that it would meet with success. Even Julia Child's former assistant, Sara Moulton, couldn't imagine how 24/7 TV cooking shows could become a thing, let alone successful.

But they did. In the beginning, Mr. Bam! himself, Emeril Lagasse, carried the network and became the first seven-figure TV chef. Eventually, Lagasse's "dump and stir" antics gave way to shows like "Good Eats" and "Iron Chef America" when other networks introduced competitive elements and started to include more non-cooking, food-related content into their line-ups. Food as entertainment might have caught fire on 24-hour TV, but nowadays, it's everywhere. Food-related content on the internet is a testament to the staying power of cooking.

TV and weight gain may be linked

According to the CDC, more than 41% of adults in the U.S. are obese. While several factors could come into play here, one of the greatest causes of obesity around the world is watching television, per a 2015 study published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. Given that the CDC has reported nearly 20% of children and adolescents are obese, one may wonder if there's a link between this issue and food-related TV ads.

During the early days of television, marketing directed at kids became a fixture of American advertising. It might be easy to poo-poo the effects of those early TV ads, but they were powerful and effective. Ads allowed the producers of Disney's "Davy Crockett" to sell an estimated $300 million of merchandise in 1955. Nowadays, sugary cereals, Hot Pockets, and Happy Meals are all fodder for ads during children's TV shows. It's suspicious that the rates of childhood obesity are three times what they were 25 years ago (via American Psychological Association), especially given the fact that, from January 2021 to December 2022, advertisers spent an estimated $1.6 billion on ads directed at kids (which included TV as well as digital campaigns). While it's no smoking gun, the link is certainly something to consider.