The Untold Truth Of The Michelin Guide

Even if you've never gone out of your way to eat at a Michelin-starred restaurant, you still know it's a pretty big deal. Chefs and restaurateurs all over the world spend their entire careers striving for being awarded — and then keeping — their Michelin stars, and it's no wonder. Since the early 20th century, it's been a definitive sign of quality, dining experience, and world-class food.

Nothing, however, is only shiny and sparkly. There's a lot of controversy that swirls around the entire idea of a Michelin star, so much so that not everyone even wants one or wants to keep what they've been awarded. It's a double-edged sword that can cause more grief and hardship than you might expect, and most of the cooking shows don't tell you that, do they? Let's look at the darker side of the Michelin Guide: the controversy, the questionable history, and the truth behind what it actually means to be awarded one of the culinary world's highest honors.

Some of the process is a bit suspect

Until former Michelin inspector Pascal Remy was sacked (for keeping detailed notes on his job) and went public, those of us on the outside believed it must be a pretty rigorous, thorough inspection process. According to him (via the LA Times), not so much.

Remy was an inspector in France, where there were more than 10,000 restaurants that were theoretically up for review. He says there were only five inspectors, though, and that's a problem. Even though the Michelin Guide revises reviews and ratings on a yearly basis, Remy said they absolutely don't visit the restaurants they're reviewing each year.

Even more surprising, Remy claimed there were some top-tier restaurants deemed "untouchable," meaning no matter how far they slid, they would always keep their three stars. He went on to say that about a third of Michelin's three-star restaurants no longer met the criteria, and that's pretty damning stuff. Michelin contested most of the claims, says Wine Spectator, but for the most part, they're still pretty hush-hush.

It's been linked to suicides

The pressure that comes with getting recognized by the Michelin Guide is intense, and in 2003 the suicide of France's Chef Bernard Loiseau was linked to his ratings in both the Michelin Guide and another restaurant guide —the Gault Millau. According to the Irish Times, Loiseau had just had his rating reduced in the Gault Millau, and there were rumors the Michelin Guide was planning on reducing his star rating as well.

A fellow chef went public with comments Loiseau had made regarding how important the ratings were, saying he was prepared to commit suicide if his stars were taken away. It wasn't until years later documents surfaced showing Michelin representatives had met with Loiseau not long before his death, expressing concerns about a "lack of soul" in his kitchen. Michelin denies any responsibility (via Eater).

Ten years after Loiseau's death, the world was asking questions about the suicide of Benoit Violier (via The Independent). A three-star Michelin chef, he spoke openly about the stress and perfectionism needed to maintain his standing, saying, "I go to sleep with cooking, I wake up to cooking."

The Michelin Curse

It might seem like once a restaurant gets awarded a Michelin star, they'd be sitting on top of the world. That's not always the case, though, and for some chefs, it causes a litany of problems.

Take Jay Fai (pictured), a 72-year-old chef who became the world's first Michelin-starred street food chef. She told News.com.au that after her award, she not only became the target of government auditors, but she and her staff struggled daily to keep crowds of customers happy. Those crowds caused other problems, and she says her neighbors now hate what her award turned their quiet little neighborhood into.

Her story isn't the only one like it. Post-Michelin-star chaos (and expectations) caused chef Skye Gyngell to quit, because she was tired of hearing her small, super-casual London cafe wasn't what customers were expecting (via The Telegraph). And when the Michelin Guide expanded into Hong Kong, restaurants who were honored suddenly found their rents raised by as much as 120 percent, crippling restaurants and forcing them to relocate or close (via Today).

It's really all about the food

When Skye Gyngell quit as chef of Michelin-starred Petersham Nurseries, she told The Telegraph her situation had become exhausting. While she lauded Michelin for expanding their recognition to smaller, more casual places, she said the idea hadn't reached the public.

"People have certain expectations of a Michelin restaurant, but we don't have cloths on the tables and here service isn't very formal. You know, if you're used to eating at Marcus Wareing then they feel let down when they come here."

But that's also a reminder that the Michelin Guide — in theory — gives out stars based solely on the quality of food, not how fancy the table looks. Food Network says the keys to getting one include things like mastering a certain cuisine while still allowing for some creativity in the kitchen, using only the best ingredients, and the sort of discipline that means diners will get the same perfect experience every night, because they never know when Michelin representatives are going to show up. Nowhere do they say anything about needing fancy dresses and tuxedos.

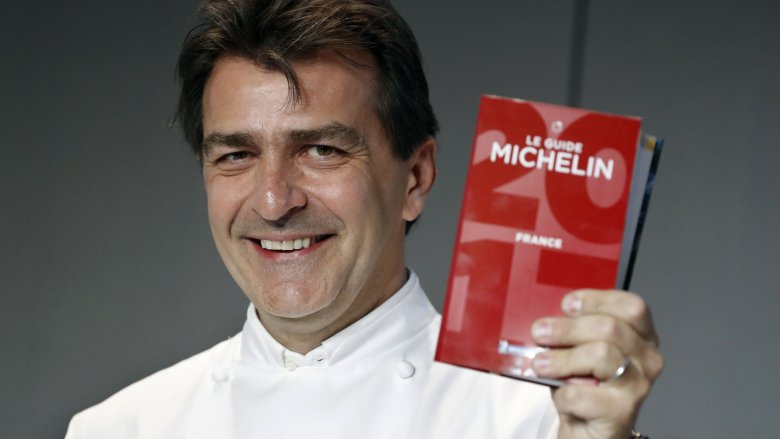

Chefs give back their stars

While some chefs spend their entire careers chasing Michelin stars, others highlight their careers by giving them back... symbolically, at least, because according to Michelin's International Director Michael Ellis (via Fine Dining Lovers), chefs can't technically "return" stars. They can, however, tell Michelin they don't want to acknowledge them.

Marco Pierre White is perhaps the most famous chef to turn his back on a Michelin rating. He was the youngest to ever be given three stars (at Restaurant Marco Pierre White), and gave them back five years later when, according to Eater, he saw people with "less knowledge than me" being given the same award. Suddenly, it didn't mean so much.

Some chefs have other reasons for refusing stars, but many share the opinion of Paris chef Alain Senderens. He gave up his stars and revamped his restaurant, saying, "I feel like having fun. I don't want to feed my ego anymore."

It's a trend that continues, as with Sebastien Bras. The French chef announced in 2017 (via CNN) that he was requesting his restaurant be left out of the 2018 guide because he, his family, and staff didn't want the pressure.

They're losing their shine

Michelin stars used to be something chefs from all walks of life could strive for, but the institution — now more than a century old — might be getting a little tarnished.

Michelin launched their Hong Kong and Macau ratings in 2009, and according to the South China Morning Post, locals were "baffled and infuriated" by the seemingly random ratings. It was called "erratic" and "peculiar," and it didn't get any clearer in the following years. In 2014, Michelin judge Gilles Pudlowski not only leaked the list of three-star restaurants ahead of the official announcement, but condemned the entire organization for what he saw as a prejudice that favored younger chefs. At the same time, Forbes says other critics pointed out they were biased against French cuisine... while still other critics claimed they favored French restaurants.

While it seemed like no one could agree on what was wrong, everyone agreed that something was. It hasn't improved, either. In 2016, critics in Vogue Korea (via ZenKimchi) condemned the Seoul Michelin Guide as being corrupt, catering to the country's elite, and awarding stars that absolutely weren't deserved.

It gets pretty sexist

In 2016, Time Money was quick to point out there was something unsettling about Michelin's newly appointed best restaurants in New York City: none featured the work of female chefs. They also pointed out that of the city's 77 Michelin-starred restaurants, only six had female head chefs. They add that while statistically, there are more male head chefs than female, the drastic underrepresentation of women in the Michelin Guide illustrates an industry-wide problem of women facing greater challenges to climb the ladder, and less pay and recognition when they get to the top.

Still doubt? In 2017, The Telegraph called out the Michelin Guide's UK branch for a massively sexist post on social media, handing out some backwards praise to the kitchen staff of Darjeeling Express. It read, in part, "It's rare to see a completely female kitchen team — and one so utterly calm under so much pressure as the place was packed." The internet reacted about as well as you'd expect, calling them "clueless" and "ridiculously patronizing."

The judges have to keep insane anonymity

Part of the Michelin Guide's inspection process is trying to guarantee every restaurant is judged the same way. Their inspectors are completely anonymous, they're never announced, and they can show up at any time.

The Telegraph scored an interview with an inspector and editor named Rebecca Burr, and reported that not only are there no pictures of her floating around the internet, but that when she appears at conferences, she speaks only from a private room via relay. She said they go to great pains to make sure no one makes them as a Michelin employee, they sometimes dine alone, sometimes, they bring a friend. They're not as thrilled about a 20- or 30-course meal as you might think, and they're on the road a lot, eating 250 meals a year at restaurants, and spending as many as 160 nights a year at a hotel.

Food & Wine also talked to a Michelin inspector, and when they asked him about how they make sure they stay anonymous, he gave an odd answer that suggests there's a lot going on behind the scenes. He simply said, "I probably shouldn't comment on this so we can all continue to remain undercover."

It has a weird connection to tires

It's not a coincidence that the restaurant world's highest honors share a name with a brand of tires — they were started by the very same people. Andre and Edouard Michelin started the guide in 1900, and it was purely for business reasons, says the UK's Business Insider. They had founded a tire company in 1889, but there was a problem: driving was still a luxury. There were only about 2,200 cars in all of their native France, and drivers could only gas up at certain pharmacies. That meant people weren't driving enough, they weren't wearing out their tires fast enough, and the Michelins weren't making the money they thought they could.

At the turn of the century, the brothers hit upon the idea of writing a travel guide to tell people about all the wonderful places they could visit... if they were to drive more. They started reviewing hotels and restaurants — and singing their praises — to push the idea that driving could take you to amazing places. They weren't wrong, and their guides ended up being so popular they launched country-specific versions and started charging for them.

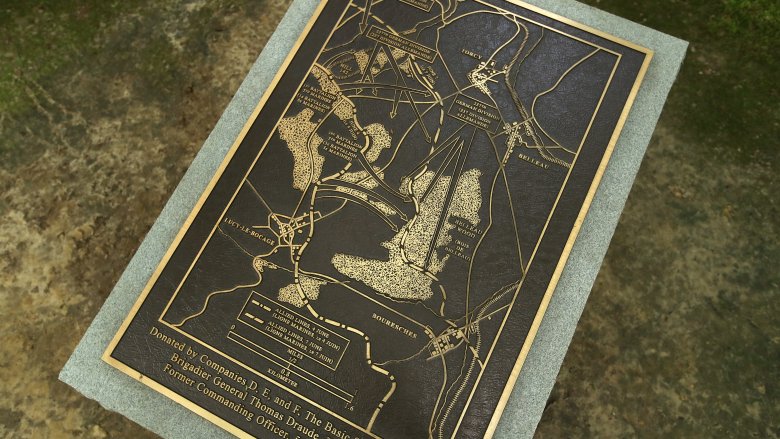

They had a foray into dark tourism

The Michelin Guide wasn't always about the restaurants, and in the years following World War I, they made a pretty dark foray into the world of tourism.

According to an article published in the Journal of Franco-Irish Studies, Michelin actually published a very uncomfortable set of guides, highlighting battlefields across Europe. Even stranger, these publications started in 1919, less than a year after the war officially ended in November 1918.

The guides were a massive success, and they sold around two million copies between 1919 and 1938. They included a history of what happened at each battlefield and a suggested itinerary for tourists, along with pictures of battlefields still littered with traces of war. Some of the text makes it clear this was an idea in the works even when the war was being fought, as the information on the Battle of the Marne was collected "even before the smoke of the battle had cleared away." That's a pretty dark way to sell tires.

It was invaluable during WWII

The Michelin Guide had been circulating for a few decades by the time World War II broke out, and during the war years, it played a pretty strange role. Like many other enterprises, publication of the guide was suspended as a huge amount of the world's supplies were funneled into the war effort. The last pre-war guide was published in 1939 (via Escoffier), and it's those guides that ended up playing a crucial part in the war.

All across Europe, road signs were destroyed and soldiers who had never been too far from home were suddenly finding themselves far afield in a strange land. But the Michelin Guides had something important: maps. When soldiers made their way across a Nazi-occupied, war-torn France, they used Michelin Guides to find their way. They were so useful that when it came time to plan the D-Day invasion of Normandy, the Allies reprinted the edition because it was so easy to use (via Straits Times).