Why People Stopped Drinking Zima

Zima is a clear, fizzy, lemon-ish-flavored beverage that was all the rage for a brief, glorious moment during the 1990s before disappearing with a lightly carbonated fizzle. Because of its meteoric rise and dizzying fall, it has achieved cult status among consumers who associate it with a very specific period in their lives.

Zima was created by Coors brewing company to boost its revenue after years of sluggish sales. Its lack of color was a savvy marketing tactic to capitalize on the "clear craze" of the early '90s that was borne out of an unfounded belief that clear products were less likely to contain harmful ingredients. Everyday purchases such as Pepsi, deodorant, and mascara were getting colorless makeovers, and Coors was ready to jump on the bandwagon.

Zima was made by filtering cheap lager through charcoal. The process rendered the beverage tasteless, prompting Coors to add a citrus-adjacent flavor (more on that later) and a hint of sweetness. After a massive marketing campaign and a carefully planned roll-out, Zima was a resounding success in its first year, selling an astonishing 1.3 million barrels when it debuted in 1993. A year later, however, these numbers plummeted by half. How did the buzzy new drink become a relic of the past in such a short period of time? The answer is more complicated and revealing than you might think.

Coors wanted Zima to be everything and nothing

The first trap that Coors fell into when formulating Zima was the desire to make the beverage tick as many marketing boxes as possible. In doing so, it created a mass of contradictions. The company wanted Zima to appeal to young consumers who already drank alcohol without taking revenue away from its pre-existing products. It spent two years engineering the drink, facilitating hundreds of focus groups, and enlisting a team of experts from marketing agencies to mastermind an irresistible beverage for the '90s consumer.

Zima was sweet but not too sweet, colorless to indicate purity but artificially flavored, and even though it had no scent or taste of alcohol, its 4.7 percent alcohol content was in the realm of a standard light beer. Its elegant, fluted bottle brought to mind a pricey liquor or wine cooler, but Coors wanted it to appeal to people who wanted an alternative to beer, not cocktails or fruity drinks.

While this gave the company plenty of material for its aggressive marketing campaign, it didn't demonstrate a confident angle on the market. The creators at Coors wanted to create something revolutionary, but the drink was just a repurposed, low-grade lager with a dubious citrus flavoring. Coors was capitalizing on the rise in diet culture, but Zima had the same alcoholic content and calories as a lager. If the company focused on engineering the drink for a niche market, then Zima might have had a fighting chance.

Its marketing campaign promised zomething different, but never delivered

Coors went all in on marketing. The commercials featured actor Roger Kabler wearing a fedora and replacing all his "s" letters with a "z." In one, he says, "Zo, you're all zet for a barbecue," he says in one, nudging some hotdogs on a grill while wearing an oversized white suit and urging people to have a Zima. In another, he leans on a table at a restaurant, seductively chewing a toothpick while a bartender tries to wrap his head around the revolutionary new beverage. When the bartender asks him what he wants, Kabler, of course, responds by asking for a "zip." The commercial ends by questioning what the product is and the catchphrase "zomething different."

The company generated an enormous amount of anticipation and interest by shrouding the drink in mystery and blanketing the airwaves with Kabler and his fedora (the marketing campaign cost Coors a cool $38 million). But it also created confusion. The Zima brand wanted to assert its product as a clear, citrusy/sweet alternative to beer but didn't want to be caught dead near the wine coolers, the category of drink that it most resembled. Coors even insisted that stores keep Zima physically distant from the wine coolers and display it next to the beer instead. This unwavering aversion to labels made Zima a confusing product that Coors struggled to market once the mystique had worn off.

Malternatives were a largely unknown quantity at the time

When Zima arrived on the market, it was the first malt-based, non-beer beverage to be offered to consumers on a national scale. These drinks, which came to be known as "malternatives," enjoyed a frenzied bout of popularity in the late 1990s and early 2000s with a cascade of brands such as Smirnoff Ice, Mike's Hard Lemonade, and Bacardi Silver. Because these drinks didn't include hops, they were defined by their lack of bitterness and added sweetness, and they appealed to casual drinkers who didn't like beer but didn't want the strong alcoholic flavor of liquor.

Zima's downfall is usually attributed to its marketing missteps and questionable flavor, but in this area, it was simply ahead of its time. The beverage was the first malternative sold nationally, and as such, it was difficult for Coors to categorize. If it had hit the shelves in 2003 instead of 1993, no one would have questioned whether it was a beer or a wine cooler because hard seltzers were ubiquitous. But in the early '90s, it had the distinction and misfortune of being the first of its kind, and as soon as brewing companies caught on to its potential, they fine-tuned the technique to create a host of superior products.

The flavor was not for everyone

Ah, that zingular taste of Zima. This, above all else, may be to blame for the drink's downfall. In a Reddit thread that asked users to describe the unique flavor of the '90s beverage, commenters compared the drink to lime-flavored scotch tape and horse urine. Others reminisced about disguising the flavor with schnapps and Jolly Ranchers.In 2002, a Slate columnist staged a malternatives tasting session with a group of friends. Their descriptors of Zima ranged from spoilt Sprite to decay. When one reported that he actually liked the flavor, his companions asked what was wrong with him. In other words, Zima was not broadly appealing in the flavor department despite all the effort that Coors poured into concocting an irresistible beverage.

Distributors warned the brewing company that customers weren't crazy about the taste and were routinely adding fruit juice and other ingredients to mask it. Coors had an opportunity to add bolder flavors to the drink to meet consumer demand, but it refused, still allergic to the potential association with wine coolers that this would entail. As a result, Zima continued to taste like Zima, a uniquely unpalatable flavor that some could tolerate and others could not. As soon as slightly less off-putting copycats came on the market, Zima's fate was sealed.

Zima found a passionate consumer base, but not the one Coors wanted

Zima was wildly successful when it launched nationwide, but its fans were exactly the opposite of who Coors was trying to target. Despite centering its marketing campaign around a male actor and insisting that stores display the product next to the beers, the company found that women were its biggest consumer base, not the manly men it was so desperate to attract. Its frustration had less to do with sexism than with the statistical realities of the alcohol industry–women, on average, drink less than men, meaning that beverages purchased largely by women have a lower profit ceiling.

Like wine coolers before it, Zima was relegated to the "female beverage" category. David Letterman skewered it on his show as a "girly-man" drink, and the male demographic shrank, further solidifying its reputation. Within a matter of years, Zima had gone from being a sell-out drink for twenty-somethings to a misogynistic punchline. Unfortunately for Coors, its attempts at damage control only made matters worse.

Coors desperately tried to switch consumer demographics with Zima Gold

Zima reached its zenith in 1994, the year it was given national distribution. It sold 1.3 million barrels that year, and as it tumbled to 650,000 barrels the following year, Coors scrambled for solutions. Realizing the public image of its brand was slipping out of its control, the company made a frantic attempt to regain the upper hand and prove that Zima was fit for alpha males. Its solution was to throw out the original concept of the beverage altogether, adding an amber color to the drink that made it look like, well, beer. Fearing that this still wasn't masculine enough, Coors increased the alcohol content to 5.4% and added a bourbon flavor.

The marketing campaign for Zima Gold had powerful overtones of desperation. One commercial depicted a sepia-toned pickup basketball game in which a group of sweaty guys shove and grimace their way to the basket. The camera hovers on dunking, glistening biceps, and high-fiving, while the tagline reads, "zomething bold." The results were disastrous. Sales of the new drink were practically nonexistent, and Coors, facing a 26% dive in its overall profits, halted the production of its hastily masculinized beverage less than four months after introducing it.

There were concerns about malternatives being targeted at teenage consumers

Zima suffered a more serious PR blow in the mid-90s when it became as clear as the drink itself that the beverage had become the illicit alcohol of choice for teenagers. Its sweet, citrusy flavor made it more akin to a soft drink than an alcoholic beverage, while its lack of color made it easy to smuggle past adults. There were even rumors that the drink couldn't be detected by Breathalyzer tests. By 1995, at least 10 states had complained to Coors about Zima, while teens conceded that the sweet flavor made it easier and more pleasurable to drink than hard liquor.

Coors hit back, defending itself by pointing to the high alcohol content and assuring authorities that it was just as detectable on a Breathalyzer as beer. In Maryland, officials tried to assuage concerns by filming a police officer drinking enough Zimas to get drunk, proving that the effects of the beverage were unmistakable. As the years went on, however, brands including Zima continued to be accused of marketing their products directly to underage drinkers. Dubbed "alcopop," these sweet, fruity beverages appealed to young people by design. While nearly all malternative brands were targeting their products at young consumers, Zima was an early lightning rod and its image never fully recovered.

Smirnoff Ice riffed on Zima's formula, so Coors responded with Zima XXX

Zima's monopoly on the malternative market faded in the late 1990s and early 2000s as other beverage companies began to roll out their own formulas. Chief among them was Smirnoff Ice, which launched in 1999 and managed to do what Zima couldn't: Appeal to men. Early commercials featured frat-boyish guys seducing women through creative means, such as turning a laundromat into a huge bubble bath. The tagline read "intelligent nightlife." In its first year, Smirnoff Ice claimed about 3% of the beer market, making Zima's meteoric rise to 1.2% of the market in 1994 pale in comparison.

Coors saw the edgy ads and "intelligent nightlife" slogan as a sign that Zima was too tame for the modern consumer. In response, it tinkered with its formula again to produce the extreme-sounding Zima XXX, a beverage with 5.9 percent alcohol and broadly appealing flavors such as Hard Orange and Hard Punch. The company, hoping to boost sales, even manufactured the Zima XXX Hard Ice Machine, which allowed bars to serve frozen versions of the reformulated drink. None of the marketing hype worked, however, and Zima XXX failed to make a dent in its rivals' profits.

Coors finally tried to embrace Zima's fans, but it was too late

Sales of Zima dropped off almost immediately after its wildly successful first year. Instead of changing the flavor that consumers complained about or leaning into its popularity among women, Coors tinkered with the formula, tried to appeal to men, and copied the marketing tactics of younger malternatives by creating Zima XXX. By the early 2000s, Zima was flagging, and Coors finally decided to accept defeat and embrace the female demographic.

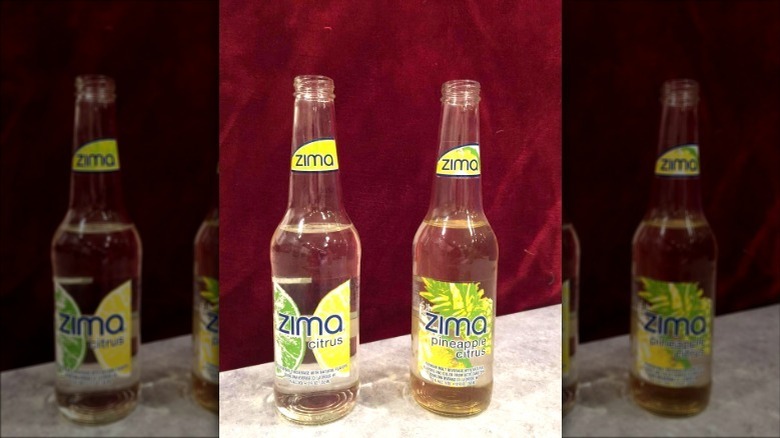

Although wine coolers had dwindled on retailer shelves since their peak in the late 80s due to high taxes, the demand for lighter, fruity alternatives to beer and wine still existed. Women in their 20s had been Zima's most loyal customers all along, and Coors finally gave them what they wanted, reformulating the drink yet again to have less alcohol, fewer calories, and a variety of fruity flavors, including Zima Citrus, Zima Pineapple Citrus, and Zima Tangerine. Had the company pivoted to this niche as soon as it realized its sales were cratering in 1995, the drink might not have had such an irredeemable and public fall from grace.

Its initial success came back to haunt it

Although Zima quickly became the butt of jokes for its rapid decline and string of unsuccessful rebrands, its legacy as one of the most disastrous beverage brands of the '90s is due partly to its momentary dominance. While other malternatives, such as Captain Morgan Gold and Stolichnaya Citrona, came and went with less fanfare, Zima stuck around for 15 years before Coors pulled the plug. Even at its least profitable, it still made the company money, suggesting that it was as much a victim of its success as consumers' disinterest.

Shortly after Zima's nationwide release in 1994, Coors estimated that 70 percent of US beer drinkers had tried the new product, an astonishing number given how many people have strong beverage preferences and aren't easily persuaded to deviate. In 1994, Coors sold 1.3 million barrels of the drink. Two years later, the number plummeted to 403,000. Even during these dwindling days, however, its sales were comparable to profitable and well-known brands like Heineken and Beck's. Viewed in this light, Zima fell prey to unsustainable profit margins and unrealistic expectations rather than low demand.

It had to be pulled out of Utah markets

In the early '90s, the government levied a tax on wine that made the production of wine coolers unaffordable for many companies. In 2008, a similar fate befell flavored malt beverages when Utah passed a bill prohibiting the sale of the fizzy drinks from grocery and convenience stores and required them to prominently disclose their alcohol content on their labels. The information had to be emblazoned in all capital letters on the front of the bottles and be approved by the alcoholic beverage control department before being shipped to the handful of liquor stores operating in the state.

The new law posed a logistical nightmare for manufacturers like Coors that would have to design new labels for its Utah supply while maintaining the original labels everywhere else. The company decided to cut its losses instead, pulling Zima out of Utah and suffering yet another hit to the profitability of the drink.

It didn't survive Coors' merger with Miller

The final nail in Zima's coffin was the merger between Coors and Miller. The companies had been long-time rivals, ranking as the third and second largest beer manufacturers, respectively. The brands finally buried the hatchet in 2007 and created a united front against the changing alcohol landscape. Americans were increasingly turning to small-scale breweries and imported beverages, leaving the large manufacturers floundering. While the merger put some much-needed wind in Coors' sales, it also sank Zima.

In October of 2008, 15 years after it first hit U.S. grocery stores, Zima was discontinued. MillerCoors cited declining consumer interest as the cause but also noted that, following the merger, there were simply too many similar varieties under the same umbrella. Since Zima was one of the least profitable products for the new company at the time, it was one of the first to go. The more popular hard seltzer Sparks, had been stealing its thunder since 2006 — though that drink would face its own challenges after falling victim to scandal over its controversial combination of alcohol and caffeine.

Zima had an even faster rise and fall in 2017 and 2018

MillerCoors rode the tidal wave of 1990s nostalgia and announced in 2017 that it would be resurrecting Zima for a limited time over the summer. Gen-Xers rejoiced at the chance to relive their Zima-flavored youth, even as a vocal few questioned whether a drink that was so derided and unappetizing should be granted a comeback less than a decade after it quietly disappeared from grocery store shelves.

The answer, as far as the numbers were concerned, was a resounding yes. Two-thirds of the re-release inventory disappeared within a month, and MillerCoors decided to bring Zima back yet again for a limited time in 2018. MillerCoors labeled the mysterious 2018 re-relaunch "Z2K" to evoke the urgency and uncertainty of the turn of the millennium and rolled out another flashy marketing campaign, this time using Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. There was even a special Snapchat filter.

Sadly (or not, depending on your point of view), Zima did not return after its 2018 limited run, and a few years later, it died another death. Despite being pulled from U.S. markets in 2008, the drink continued to be sold in Japan, where its popularity remained steady. After the COVID-19 pandemic caused sales to plummet, however, Molson Coors Japan shuttered, removing Zima from circulation.